Kypseli and its Market: conflict and coexistence in the neighbourhoods of the city centre

Lafazani Olga|Vaiou Dina

Ethnic Groups, History, Quartiers

2015 | Dec

Kypseli, one of the oldest neighbourhoods in the Municipality of Athens, is currently one of the most densely populated and multi-cultural neighbourhoods and an example of coexistence between locals and migrants; the terms of coexistence, as it is to be expected, change over time, in accordance with general developments in the city and beyond.

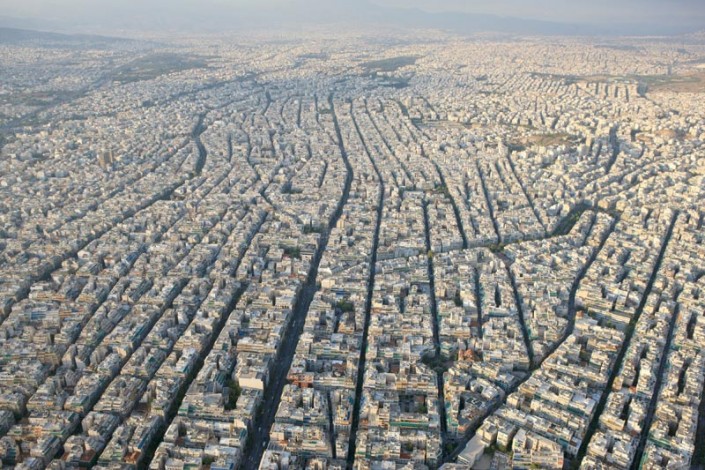

Photo 1: Street in Kypseli (migrant shops are marked in colour)

Source: greekscapes

Brief history of urbanisation

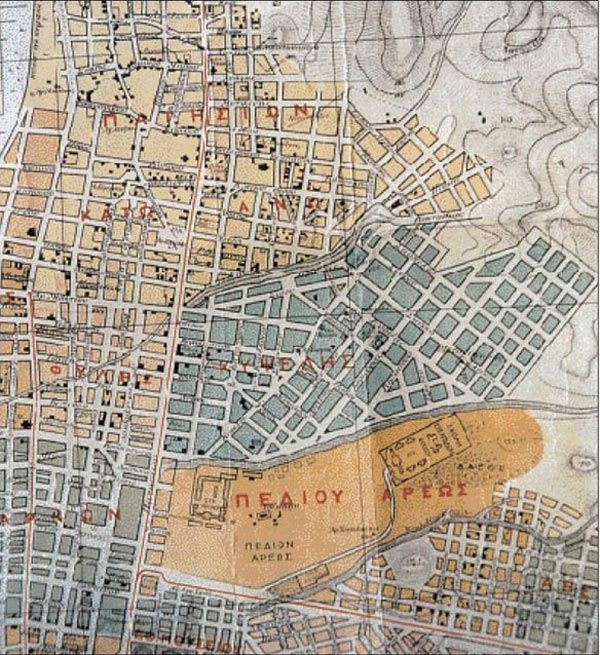

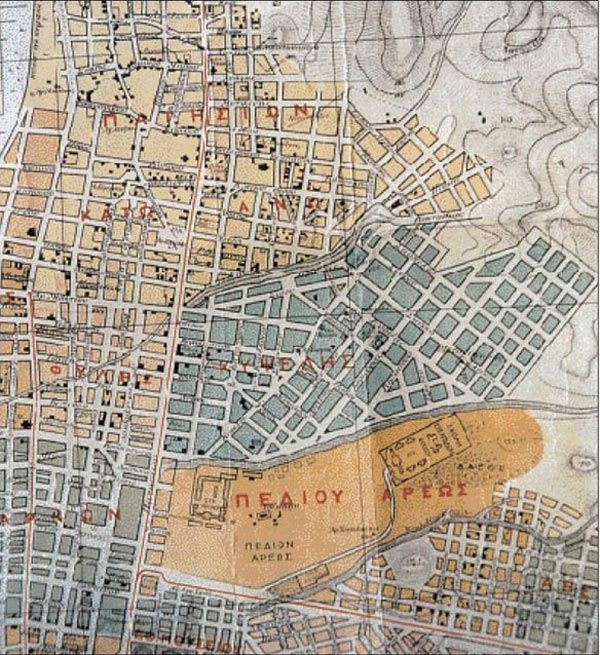

In the beginning of the 20th century, when the first villas started to be built, Kypseli was still an area of farms and scarce cottages. Until the inter-war period, it remained sparsely populated; but the influx of internal migrants from the countryside to the capital began transforming it into an urban neighbourhood with detached and two-storey houses. With the extensions of the Town Plan in 1930, it more or less acquired its current land surface, while the first apartment buildings were built, mainly for affluent families. (Photo 2). In 1937, architect Vassilios Tsagris designed the transformation of Levidi stream (currently Fokionos Negri str.) into a linear garden with trees, water fountains, sculptures and play areas (Photo 3) In the same period, the local Municipal Market was also constructed.

Photo 2: Kypseli urban plan

Source: Βασενχόβεν 2003

Photo 3: Fokionos Negri str. in the urban tissue of Kypseli

Source: greekscapes

Intense urbanization started after World War II, as is the case with many areas in Athens, using the exchange-in-kind (antiparochi) system, and continued rapidly up to the 1970s. Thus, the current looks of the neighbourhood gradually took shape, a neighbourhood which, according to all planning reports, it is one of the most problematic areas of the Municipality of Athens, with high population densities, pollution, traffic and parking issues, extremely limited open spaces and inadequate infrastructures. New apartment buildings have replaced single family houses, while at the same time Kypseli becomes famous for its night life, theatres, cinemas, pastry shops and restaurants. Since the mid-1980s, a tendency of younger families to move towards the north-east and south-east suburbs can be identified. However, older residents remain in the area, mainly in the upper floors and larger apartments of apartment buildings.

The 1990s is a turning point for Kypseli: the mass settlement of migrants reverses the trends towards decrease of population and of average household size, as well as age profile. The “flight” of younger families is gradually compensated by the settlement of large and young migrant households. The features of the neighbourhood which constituted signs of deterioration of the quality of life for old residents, acquired different meanings for migrants. Apartments, mainly in basement or ground floor level, even washhouses on the roofs, that old residents consider poorly constructed or extremely small, are quickly rented by migrants, who refurbish them through personal labour and manage to lower their rent expenses by cohabiting often with strangers. Thus a large part of the building stock that had been devalued and/or empty for a long period of time, was re-inserted in the real estate market.

At the same time, the geographical location of Kypseli, whose old residents left due to the noise, pollution, lack of green spaces and parking areas, offers migrants accessibility, efficient means of transport, neighbouring schools and a considerable possibility to combine relatively easily paid work in other areas of the city with care for the family and children.

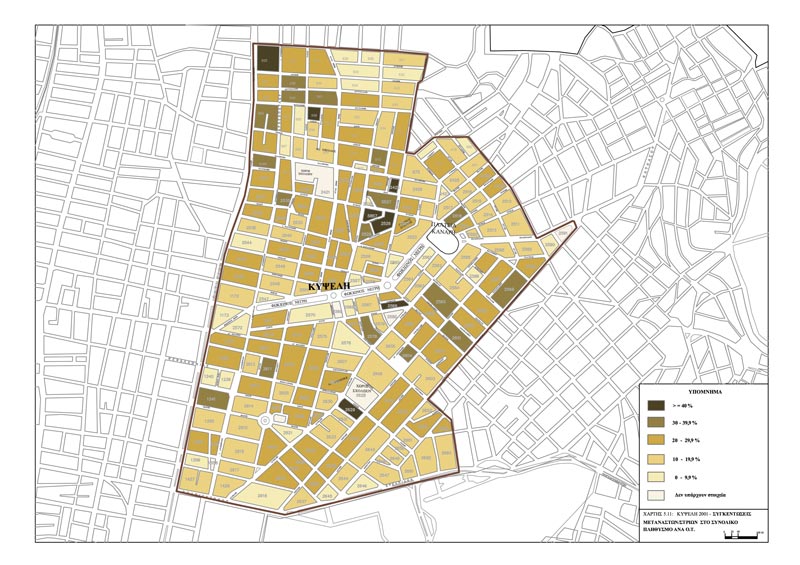

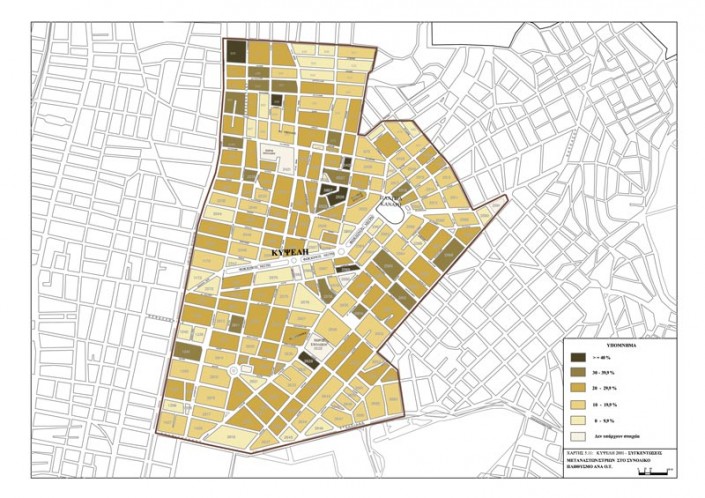

According to the 2001 Population Census, men and women migrants mainly from Albania, Romania, Bulgaria, Ukraine, but also Moldova, the Russian Federation, Georgia, Yugoslavia, Armenia, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Ghana , South Africa, Egypt, the Philippines, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and Syria, compose, albeit with different dynamics and population sizes, the mosaic of “new” residents of Kypseli. Apart from their multiple origins, it is important to underline the relatively high level of education (particularly among migrant women from Eastern Europe) and the high percentage of economically active population, both in the formal and the informal economy. (Map 1).

Map 1: Migrant population distribution by census track

Source: Population Census 2001 (elaboration Βαΐου et al 2007)

Notwithstanding the urban transformations it has undergone over time, Kypseli retains a number of important features, including a big variety and mixity of land use, with an emphasis on housing, leisure and commerce, as well as a densely constructed and populated urban fabric, with densities exceeding 350 residents/Ha. The presence of a high number of migrants, who settled there since 1990, contributed to the development of activities and services oriented to the “new” population, but also revived some of the old uses. The distribution of urban functions, as well as population, is obviously not homogeneous. On Fokionos Negri, an established supra-local pole of leisure and entertainment, one finds public services and banks, the most expensive restaurants, pastry shops and cafeterias, some operating continuously since the 1960s, as well as the most expensive apartments (this is why no migrant residences are registered along the street). In peripheral blocks, there are neighbourhood coffee shops, migrant shops and local services (bakeries, grocery stores, hairdressers, dry cleaners, call centres, money transfer services, plumbers, electricians, workshops etc.).

The Municipal Market

The Municipal Market of Kypseli was built in the 1930s, following a typology that was common at the time, and operated as a food market until 2003. At that time there were plans to turn it into a multi-storey mall and parking. But, following the action taken by the municipal group “Anoihti Poli”, it was finally listed in 2005. In the end of 2006, the closed building was squatted by a group of residents who renovated it with personal work and resources. With this symbolic gesture, the “Open Municipal Market Squat” contributed to re-activate the space and integrate it into the neighbourhood’s everyday life through cultural and other activities.

The idea of operating an alternative space with multiple and dense activities gradually took shape, as numerous resident groups took initiatives and kept the space alive. In the six years of its operation, a number of activities and events took place there, among which the Migrants’ School, where volunteers offered free Greek language classes to migrants from the neighbourhood and beyond, the market for organic foodstuffs, literary and cinema nights, concerts, cultural and political events, multi-ethnic collective kitchens, people’s assemblies, a lending library, exhibitions etc. These activities established the Market as an important public space in the neighbourhood and an attraction point for residents and visitors, both local and migrant, women and men (Photo 4 and 5).

Photo 4: Migrant event in the Municipal Market of Kypseli, 2009

Source: O. Lafazani, personal archive

Photo 5: Migrants’ School in the Municipal Market of Kypseli, 2009

Source: O. Lafazani, personal archive

In August 2012, in the presence of a public prosecutor and police forces, the Municipality of Athens reclaimed the Market in order to assign it to (some other?) residents. Since then, only a small part of it is used as a Citizen Service Centre.

Aspects of co-habitation among locals and migrants

For three decades, local and migrant women and men live together in Kypseli, in ways that have been undergoing continuous transformations, while at the same time transforming the neighbourhood. Migrant men and women who live here since the early 1990s have established vital attachments to the neighbourhood, while some emigrate again due to the crisis. Migrant children born in Kypseli are practically locals – whether they gained or not the institutional right to Greek citizenship. Newcomers try to establish an everyday life for themselves in Athens or aim to continue their trip to other destinations. In this context and always in relation to more general economic, social and political circumstances, a complex web of relations gradually takes shape, often characterised by mixed feelings, suspiciousness, awkwardness, but also good will, mutual assistance, collaboration and solidarity, making Kypseli a special case of cohabitation.

Informal networks of mutual assistance formed in Kypseli in many ways seem to substitute for the lack of formal integration policies; they have to do with assistance to find a job or a flat to rent as well as with general support in everyday life. Support between local and migrant men and, most importantly, women is mutual and acquires a major significance at times of crisis and of dramatic cuts in salaries and services, since it redefines in various ways the meaning of neighbouring and neighbourhood. Here the social life of migrant women, the sense of companionship and acceptance by local women as well as their everyday practices contribute to a sense of belonging in the neighbourhood and the city. Meetings with friends in squares and other public spaces, accompanying children to school or to the playground, daily shopping and the routes followed for the daily care of the family, form new spaces and points of meeting, getting together and mingling among neighbourhood residents, “local” or “migrant” (Photo 6).

Photo 6: Kanari Square 2007

Source: D. Vaiou, personal archive

The Open Municipal Market Squat and its multiple activities does not exist any longer. Apart from informal networks, however, there seem to appear organised collective initiatives for mutual assistance and support, which involve local and migrant women and men. Among such initiatives, “Myrmighi” (the “Ant”) is a Solidarity Network in the neighbourhood whose role is very significant for residents in difficulty. Three decades since the initial settlement of migrants in Kypseli, the reasons that render it a special and familiar place seem to be common among migrant women and men and older residents. The creation of familiar places to which old and new residents become attached in multiple ways and eventually consider as their own, (may) lead to a re-definition of who belongs in the neighbourhood, who can be accepted as a member of an everyday community, how belonging materialises locally.

Migrants in Kypseli continue to live in their small apartments at the lower floors of buildings and add their own colours to the neighbourhood (Figure 1). At the same time, having become familiar with the neighbourhood and the city, they are no longer “strangers”, even though the thorny issue of “legalisation” remains unresolved. The remaining locals still live in their comfortable top-floor apartments and discover, in contradictory ways, the virtues of mutual respect, if not active co-existence. Co-existence in and of itself is not a guarantee for acceptance of the “other”, as many recent events that took place also in Kypseli remind us. However, as migrant women and men stop being a homogeneous group of “strangers”/”others” and acquire names, nationality, gender, age, history, cultural and social characteristics and a voice of their own, a major step is made to fight stereotypes, accept the “other”, build relations of neighbouring which are in no way free of tensions and power relations.

Figure 1: Distribution of migrant housing per floor

Source: Βαΐου et al. 2007, 76

Relations constituted in the everyday lives of residents in a neighbourhood such as Kypseli are a “counter-example” against an increasingly powerful public discourse which criminalizes migrants and connects them -directly or indirectly- with the degradation of central neighbourhoods, with crime and insecurity. Contrary to a discourse describing the city centre as “ghetto”, a deeper study of processes and relations developed in the realm of the everyday brings to the fore difficulties and problems but also relations of solidarity, mutuality and coexistence and, in this sense, challenges hate arguments and accepted practices but also urban policies and institutional arrangements.

Entry citation

Lafazani, O., Vaiou, D. (2015) Kypseli and its Market: conflict and coexistence in the neighbourhoods of the city centre, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/kypseli/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.33

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Βαΐου Ν (2007) Διαπλεκόμενες καθημερινότητες και χωρο-κοινωνικές μεταβολές στην πόλη. Μετανάστριες και ντόπιες στις γειτονιές της Αθήνας. Αθήνα. Available from: http://iktinos2.arch.ntua.gr/genspace/pithagoras.pdf.

- Βαΐου Ν, Λαφαζάνη Ό και Λυκογιάννη Ρ (2013) Πρακτικές συνύπαρξης στις γειτονιές της πόλης. Συναντήσεις στην Κυψέλη. 1η έκδ. Στο: Ζαββού Α, Καμπούρη Ν, και Στρατηγάκη Μ (επιμ.), Φύλο, Μετανάστευση, Διαπολιτισμικότητα, Αθήνα: Νήσος, σσ 71–102.

- Βασενχόβεν Λ (2003) Η γενεαλογία της Κυψέλης. Επτά Ημέρες, Η Καθημερινή, Αθήνα, 23ο Φεβρουάριος.