Locating retail commerce and craft industry in Athens 1830-1925

Potamianos Nikos

Economy, History, Social Structure

2017 | Nov

In the century that passed from the years of the Ottoman domination until the arrival of the refugees from Asia Minor in the Interwar period, Athens changed radically. Previously a medium-sized city of the Ottoman Empire, with a population of almost 10,000 people, it became the capital of a new national state and grew with it, reaching a population of 300,000 people, while it expanded in all directions, something that led to the creation of numerous new neighborhoods. The new capital was symbolically upgraded, important neo-classical buildings were erected, while it became the seat of the first university in eastern Mediterranean and the intellectual centre of the wider Hellenism. Apart from being an administrative centre it was quickly established as a commercial centre as well, with its stores providing the countryside with commercial goods. Finally, Athens after 1870 entered the industrial age, up to a point, but small artisan units were mainly responsible for the productive activities in the city (Αγριαντώνη 1995: 163).

The model for spatially locating the commercial and productive activities changed as well. These activities were no longer located in the bazaar but spread out in shops all over the city, something that was accompanied by new forms of spatial concentration, different ones depending on each profession. The developments in handicrafts, the retail commerce of food and of goods not for everyday use will be examined separately, and our findings from the quantitative processing of data for two professions, the carpenters/cabinetmakers and barbers, will be presented.

Before we move on, two clarifications. First, our analysis will be limited to small and medium businesses. We have, however, a general idea about big businesses in the beginning of the 20th century. Regarding retail commerce, department stores and super markets did not exist at that time; the big stores of that period were largely situated at the centre of the city, similarly to the banks. It seems that the same thing happened with wholesale, while industries, like the Poulopoulos hat factory in Petralona or the factory of Pyrris that manufactured undershirts in Ambelokipoi, were generally located at the outskirts of the city: at districts where people of the working class lived, where the land was cheaper and the various uses that caused a disturbance were going to disturb less. Second, goods and services were provided not only from stores but also from street sellers, who also took advantage from the increase of consumption that came together with the increase of the population. The “sedentary” vendors, whose numbers increased greatly after the arrival of the refugees, set their benches on the street, at the same place every time, usually at the centre of the city. The proper “itinerant traders” served especially the most remote popular districts, where the network of stores was less dense.

Our starting point is the bazaar. At the pre-modern city, both in the Ottoman East and western Europe, the workshops and the stores were generally located at the same area and were separated from the residential zones (it is obvious that this rule had several deviations and exceptions: Faroqhi 1994: 586-587). This tendency for spatial concentration mainly aimed at the better control of prices and the quality of products and the implementation of various other regulations from the authorities of the city and from the guilds. According to McGowan 1994, 696, from the 18th century and onwards the craftsmen pursued being gathered in an area, following a strategy for preserving their rights of monopoly that were threatened as the guild system gradually declined. This tendency of each profession to gather in a specific area slowed down with the decline of the guilds – and it seems not only where the institutional framework changed radically, as was the case in Greece, but also in the Ottoman Empire (regarding Thessaloniki see Χεκίμογλου 1998). In Athens the dissemination of the commercial activities in the urban network had already begun by the end of the Ottoman rule (Καρύδης 2000: 143).

However, simultaneously with the tendency to disseminate all over the city, businesses continued to gather together and the reasons are various: first of all there was economic pressure for the shops to be at fixed marketplaces, according to the various fields; second, due to the fact that the people tended to do things as they were used to do and that the arrangements that were made in the past determined the present; and thirdly because in the new institutional framework of the Greek state some shops that sold food continued to be subjected to controls by the authorities, which pursued the reproduction of the model of the bazaar for these specific shops. Police could impose a specific location on the shop owners, while the municipalities undertook to create covered markets and to rent their stores to shop owners of specific professions, in profitable prices for them, achieving thus the maintenance of a fixed marketplace which could be supervised easily regarding, for example, hygiene rules. Large covered markets were built in the 19th century from Pyrgos to Ermoupolis, while this model appears even in the interwar period (in Athens with the Market in Kipseli) [1].

Let us start with the “commercial stores”, the shops that sold textiles, clothes, shoes, glassware etc. It seems that some European merchants were the first to leave the bazaar and then local merchants followed suit, with pioneers those shopkeepers who wanted to have the middle class as their clientele (Καιροφύλας 1999). The connection of the new consumption standards with the stores that opened in the new city, at Ermou and Aiolou streets and the surrounding alleys (Χατζημιχαήλ 2011: 76) led to the gradual decline of the shops of the old market and its region. Flurries of establishment of stores at the present-day commercial centre took place in the 1860s and the 1890s (Λώζος 1984), while the establishment of more specialized “luxury stores”, like perfumeries and floristries, increased the glamour of the new commercial centre; shop windows and lights helped Athens achieve the appearance of a big urban centre (Ακρόπολις 11 Οκτωβρίου 1888).

The picture that one perceives from the commercial guides that were published from 1875 to 1925 consisted at one hand of the existence of most types of stores in all neighborhoods, and on the other of the strong tendencies of similar stores to gather at districts in the centre of the city –which was related predominantly with the stores that didn’t sell items for “everyday use” and needed a pool of customers larger than a single neighborhood (Ball 2001). With a casual look we see various fixed marketplaces appearing in various locations of the commercial triangle of Athens: for example all the shops that sold men’s hats that were recorded in the guide of 1875 were located in Aiolou street and women’s hats in Ermou street; this distribution changed when Stadiou street also emerged as a commercial street, with women’s items in 1898 remaining in Ermou but men’s items moving to Stadiou, while Aiolou was filled with stores but of a lesser category (Ακρόπολις 27 Οκτωβρίου 1898). The concentration of the stores that were addressed to a more popular public on the western side of the commercial centre, as an extension of the old market, is confirmed by the guide of 1899, where for example all the stores with the “ready-made clothes” recorded were in Athinas street and Dimopratirio square.

A second category is the food stores. Bakeries and groceries were scattered from an early period in every corner of Athens, but for butcher’s shops, fish shops and greengrocer’s shops the development was different, since the state took care to determine spatially the market of fresh food. Until 1884 they remained to a large extent at the Old Market, whose wooden shacks were rented by the municipality to the merchants, as well as at temporary neighborhood markets in Psiri and Neapoli [2]. Particularly regarding the butcher’s shops and the fish shops hygiene reasons were more important and the regulations stricter, with the police forbidding their operation outside specific locations (for example Μπουκλάκος 1874: 415-416). In any case, permits from the municipality for the operation of butcher’s shops and greengrocer’s shops outside the markets were given very rarely before the 1880s (Ποταμιάνος 2011: 100). This policy changed both due to the expansion of the city and the need to service the new neighborhoods and due to the difficulties caused by the destruction of the Old Market by a fire in 1884. The model of the central market weakened in the end of the 19th century but it was not abandoned. Varvakios Market, whose construction was completed in 1886 (Μπίρης 1999: 169), continued to attract all the fish sellers and 40% of the butcher’s shops (Άστυ 14 Μαρτίου 1894). Finally, the establishment of the covered vegetable market at Pireos street in 1901, as an area that served the transportation of vegetables of Kolokynthou and Rentis and their subsequent wholesale, fell within the period in which the greengrocers’ shops disseminated all over the city.

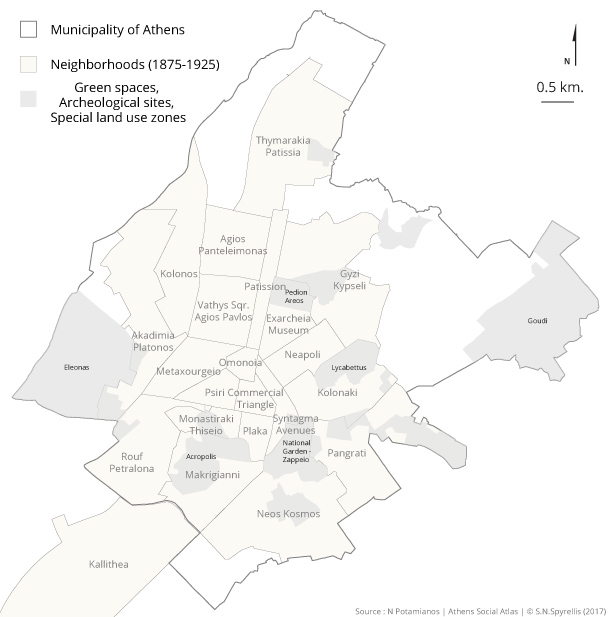

Map 1: The athenian neighbourhoods 1875-1925

The final distinct category of stores is craft industries. The workshops were the first stores that disseminated to the city, although in the 1830s they continued to be located mainly in the area west of Ermou street (Χατζημιχαήλ 2011: 75). Also under the Ottoman rule a lot of the workshops were located outside the Market, since they needed space or water (Τραυλός 1993: 218-219). Of course a lot of the crafts continued to be determined spatially (in their majority but not exclusively) on the basis of the rationale of the fixed marketplace. Exemplary here is the study by Agriantoni (Αγριαντώνη 1995) regarding Metaxourgeio and the process of concentration of “heavy industries” there (metallurgy, carpentry etc.): sometimes the location of the fixed marketplace was defined by the older operations of the city that have become an integral part of its structures, with the characteristic example of the wheelers at the old transportation avenue at the end of Ermou street.

Crafts were scattered both at areas of the centre (especially the non-disturbing activities of manufacturing clothes and shoes) and the working class neighborhoods. The institutional framework of state regulation generally allowed it: the relevant decree of 1835 provided that for the foundation of certain crafts with “harmful influence” it was necessary to have the permit of the police and the consent of the neighbors, while “the other workshops, with ugly smells or loud noises are sent to neighborhoods far from the centre of the city” (ΦΕΚ 19, 15 Μαΐου 1835). How strictly the decree was implemented is doubtful, and certainly the expansion of Athens changed the prerequisites according to which an area was considered to be more “remote”: therefore, one encounters in the press the protests of the neighbors and requests for the removal of the craft industries from their neighborhood (Ποταμιάνος 2011: 96). The only case where we detected an attempt by the state to determine spatially with accuracy the territory of a craft this was the most disturbing one: blacksmiths. A police order in 1874 (Μπουκλάκος 1874: 360) τlimited them at the streets of Ifaistou and Adrianou after Monastiraki (that is at “Gyftika”, “the district of Gypsy smiths”, where they were located from the older days: Χατζημιχαήλ 2011: 79) and the district of Metaxourgeio. In the beginning of the 1890s there was a discussion for their orderly relocation at Iera Odos street (Άστυ 26 και 31 Ιανουαρίου, 31 Μαρτίου, 9 και 30 Απριλίου 1894). The reactions of the blacksmiths averted the realization of these plans (Παπαδιαμάντης 1896), and in 1928 Ifaistou street remained the main location of the blacksmith’s shops (Αθάνατος 2001: 38-46).

Table 1: Distribution of carpenters and cabinetmakers in the neighbourhoods 1875-1925

Table 2: Distribution of carpenters and cabinetmakers in the neighbourhoods 1875-1925 (%)

Overall, the international tendency towards the removal of the manufacture from the wider city centre –leaving it monopolized by retailing and financial activities– became also evident in Athens, albeit weaker and somewhat delayed in time. This becomes obvious by the quantitative processing of data for the various professions of wood processing that we gathered from the commercial guides and the registries of the Commercial and Industrial Chamber for the period 1875-1925 (Tables 1 and 2). The data is of course uneven, since they come from commercial guides of varying credibility –while the commercial guides in general tended to reduce the number of neighborhood shops. For example in the guide of 1919, the shops at the centre are overrepresented, while the data from the Chamber’s registry for 1925 are more complete: the combination of the two sources portrays a picture of abrupt removal from the centre which was probably not real. The tendency towards the removal of craft industries from the centre of Athens is confirmed if we compare the reduction of the absolute number and percentages of the central carpenter’s workshops, etc. from 1910 to 1925 with the much smaller respective one of the barber shops of the centre in the same period of time (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3: Distribution of barber shops in the neighbourhoods 1875-1925

Table 4: Distribution of barber shops in the neighbourhoods 1875-1925 (%)

New concentrations of stores of the same type kept on being created after craft industries were removed from the centre of the city (Tables 1 and 2). From early on there were a lot of carpenters etc. in Neapoli, while another concentration was located northwest at the district of Vathi and at Metaxourgeio (which in 1925 extended at Agios Panteleimonas and Kolonos); another fixed marketplace emerged at the new southeastern neighborhoods (Makrigianni-Neos Kosmos-Pangrati). However, the new fixed marketplaces created they do not have the strength of the older ones. Regarding the distribution of the stores at the city centre, remarkable is the stability of the area around the old market, where craft activities were accompanied by stores that sold cheap furniture (while the expensive furniture stores were located mainly at the area of Syntagma and the avenues that connected it with Omonoia).

Map 2: Spatial distribution of carpenter shops (1875-1925)

Let us close by commenting the differences at their spatial distribution between barber shops (Tables 3 and 4) and carpenter’s shops, but also “commercial stores” and the stores selling fresh food. At a period where razor blades were not yet imported in great numbers and moustaches dominated the faces of men, visiting the barber for a shave took place frequently and this made the barber shop one of the busiest stores. The dispersion of the barber shops in the city should resemble the one of bakers and groceries, as well as the cafes and the taverns: generally they are more evenly distributed, and with greater presence at the remote districts; these characteristics appear enhanced at the Chamber’s registry. Barber shops constituted a type of store that was scattered in the neighborhoods, and their degree of density should have depended on the population of each district. Of course, a model of higher concentration in the urban centre appears in the barber shops as well; however, we should not forget that the centre continued to be a residential area, especially of the higher classes (Dimitropoulou 2008: 232-239). Here also, the area of Syntagma, Stadiou street etc. is where the more luxurious stores were located (those that are defined in our sources as “hair salons” and those that sold perfumes at the same time: Ποταμιάνος 2015: 68 και 70).

The remarkable percentages of the area around Omonoia, finally, remind us another characteristic of the barber shops as shops: they were a traditional area of male sociability –and it seems reasonable that they gathered at an area which, among others, was an entertainment centre that attracted people from the whole city (with cafes, confectioneries and other entertainment places).

Map 3: Spatial distribution of barber shops (1875-1925)

[1] This was no Greek peculiarity: about London and Manchester in 1850 see Alexander 1970: 85 and Scola 1992: 231.

[2] For the regular, until the end of the 19th century, discussion at the municipal council regarding the erection of small local markets in order to cover the needs of the districts see Παρασκευόπουλος 1907.

Entry citation

Potamianos, N. (2017) Locating retail commerce and craft industry in Athens 1830-1925, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/crafts-and-retailing-in-athens-1830-1925/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.77

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Αγριαντώνη Χ (1995) Συνοικία Μεταξουργείο. Στο: Χατζηιωάννου Μ-Χ, Ζιούλας Χ, Παπανικολάου – Κρίστενσεν Α, κ.ά. (επιμ.), Το Μεταξουργείο της Αθήνας, Αθήνα: Κέντρο Νεοελληνικών Ερευνών Εθνικό Ίδρυμα Ερευνών (ΚΝΕ – ΕΙΕ), σσ 157–171.

- Αθάνατος Κ (2001) Ταξείδι στην παλιά Αθήνα. Δώδεκα άρθρα από το «Ελεύθερον Βήμα» (1928). Παπαγεωργίου Ε (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Πολιτιστικός Οργανισμός Δήμου Αθηναίων.

- Καιροφύλας Γ (1999) Οι πρώτοι έμποροι των Αθηνών. Αθήνα: Φιλιππότης.

- Καρύδης Δ (2000) Χωρο-γραφία νεωτερική ή λόγος για τη συγκρότηση και εξέλιξη των ελληνικών πόλεων από τον 15ο στον 19ο αιώνα. Αθήνα: Συμμετρία.

- Λώζος Α (1984) Η οικονομική ιστορία των Αθηνών. Αθήνα: Εμπορικό και Βιομηχανικό Επιμελητήριο Αθηνών.

- Μπίρης Κ (1966) Aι Αθήναι από του 19ου εις τον 20ον αιώνα. Αθήνα: Έκδοσις του Καθιδρύματος Πολεοδομίας και Ιστορίας των Αθηνών.

- Μπουκλάκος ΓΘ (επιμ.) (1874) Συλλογή των Αστυνομικών νόμων, διαταγμάτων, διατάξεων και κανονισμών. Αθήνα.

- Παπαδιαμάντης Α (1896) Αι Αθήναι ως Ανατολική πόλις. Στο: Η Ελλάς κατά τους Ολυμπιακούς Αγώνας, Αθήνα: Ακρόπολις, σσ 293–295.

- Παρασκευόπουλος ΓΠ (1907) Οι δήμαρχοι των Αθηνών (1835-1907). Αθήνα: Ρουφτάνη – Παππαγεωργίου.

- Ποταμιάνος Ν (2011) Η παραδοσιακή μικροαστική τάξη της Αθήνας : Mαγαζάτορες και βιοτέχνες 1880-1925. Πανεπιστήμιο Κρήτης. Available from: http://elocus.lib.uoc.gr/dlib/6/f/8/metadata-dlib-1330425501-380121-25886.tkl#.

- Ποταμιάνος Ν (2015) Οι νοικοκυραίοι. Μαγαζάτορες και βιοτέχνες στην Αθήνα 1880-1925. Ρέθυμνο: Πανεπιστημιακές Εκδόσεις Κρήτης.

- Τραυλός Ι (1993) Πολεοδομική εξέλιξις των Αθηνών από των προϊστορικών χρόνων μέχρι των αρχών του 19ου αιώνα. 2η έκδ. Αθήνα: Εκδόσεις Καπόν.

- Χατζημιχαήλ Υ (2011) ‘Συμβαλλόμενοι εν Αθήναις…’. Οικονομικές και κοινωνικές όψεις της Αθήνας στο πρώιμο ελληνικό κράτος (1833-1843). Πανεπιστήμιο Κρήτης. Available from: http://elocus.lib.uoc.gr/dlib/9/0/f/metadata-dlib-1327572796-928499-9482.tkl.

- Χεκίμογλου Ε (1998) Τα επαγγέλματα στη Θεσσαλονίκη: μια αναδρομή στην Οθωμανική περίοδο. Στο: Δάγκας Α (επιμ.), Συμβολή στην έρευνα για την οικονομική και κοινωνική εξέλιξη της Θεσσαλονίκης: Οικονομική δομή και κοινωνικός καταμερισμός της εργασίας 1912-1940, Θεσσαλονίκη: Επαγγελματικό Επιμελητήριο Θεσσαλονίκης και Οργανισμός Πολιτιστικής Πρωτεύουσας.

- Alexander D (1970) Retailing in England during the industrial revolution. London: Athlone Press London.

- Ball M (2001) Η εκτατική αστική οικονομία. In: Massey D and Allen J (eds), Η γεωγραφία έχει σημασία!, Πάτρα: Ελληνικό Ανοιχτό Πανεπιστήμιο, pp. 85–103.

- Dimitropoulou M (2008) Athènes au XIXe siècle : de la bourgade à la capitale. Université Lumière, Lyon II. Available from: http://theses.univ-lyon2.fr/documents/lyon2/2008/dimitropoulou_m#p=0&a=top.

- Faroqhi S (1994) No Crisis and change, 1590-1699. In: Inalcik H and Quataert D (eds), An economic and social history of the Ottoman empire, 1300-1914, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 411–635.

- McGowan B (1994) The age of the ayans, 1699-1812. In: Inalcik H and Quataert D (eds), An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 637–757.

- Scola R (1992) Feeding the Victorian city. The food supply of Manchester, 1770-1870. Manchester: Manchester University Press.