Cosmopolitan Athens: the communities of Western Europeans in Athens in the 19th century

Potamianos Nikos

History, Social Structure

2017 | Dec

The role of 19th c. Athens as a national centre has been often highlighted in the literature. It was a “national centre”: the capital of the new Greek state, the first nation-state in the Eastern Mediterranean, and a cultural centre of the Hellenic world. Athens was the seat of the first Greek-speaking university, attended by Greek speaking students from the Balkans and the Near East.

Less attention has been paid to the character of Athens as a Mediterranean and quite cosmopolitan city. It seems that this international character of Athenian society has been neglected not only by historians but also by novelists. Before the “study of the naturalization in the Greek soil” of foreigners such as Liapkin or Jungermann by Karagatsis in the interwar years, hardly any European inhabitants of Athens can be found among the characters of Greek literature. This paper constitutes a first approach to the issue of the settlement of foreigners in 19th c. Athens -and of their gradual assimilation over the generations. We will not attempt to discuss the settlement of people from the Ottoman Empire and the Balkan states: we will focus on the communities of Athenians from the rest of Europe.

Some Europeans had settled in Athens already from the 18th century: in 1810 Hobhouse refers to 7-8 households of “Franks” (i.e. western Europeans). The ancient monuments attracted European travellers; their number kept increasing from the end of the 18th century onward, so that the local servant of Hobhouse assessed that “soon a tavern will open in Athens” (Hobhouse 1813, τ.1, σ.302).

By the end of the 19th c. the Europeans who visited ancient monuments constituted a small tourist wave. The settlement in Athens, of archaeologists from all over Europe, as well of amateur archaeologists such as Schliemann, became more regular with the foundation of the French Archaeological School in 1846, the German in 1874, the British in 1885 etc.

The turning point regarding the settlement of “foreigners” (including Greeks from other countries) in Athens was the move of the capital of the independent Greek state to Athens, in 1834. The embassies of other European countries, as well as the Royal court and the central administration which were initially staffed with foreigners, functioned as magnets and played crucial role in the consolidation of the Western European communities in Athens. Bureaucrats and scientists, missionaries and opportunists, entrepreneurs and diplomats settled in the new capital, together with Philhellenes who fought in the revolution of 1821 against the Ottoman Empire and decided to stay in the liberated country. The Royal court and the embassies became the nuclei around which a cosmopolitan “society” was created, consisting of “Franks”, Greeks coming from abroad as well as members of the local elite. Memoirs, diaries and letters of ladies of the court such as Lyt or Plȕskow provide a vivid picture of the meetings of those circles and of the extent to which the social life of the newcomers was supported by their compatriots.

Thousands of Bavarians and other Germans came to Greece following king Otto from 1833 onward. They were by far the biggest foreign population influx at the time. The new administration sought to staff the mechanisms of the State with educated and experienced civil servants, as well as to build an army they could trust. Moreover, from the 5.000 Bavarian soldiers who came to Greece in 1834-38, more than 1.000 were technicians with skills that the country was lacking, like road construction etc. A large part of those newcomers concentrated in Athens, working in the administration as well as establishing printing-houses, bookshops, hotels, restaurants and pharmacies. After the revolution of 1843 and the end of the absolute monarchy in Greece, most Bavarian officials, soldiers and civil servants left the country. However, many of them stayed behind, as they were married with Greek women or were well-established artisans, shopkeepers and professionals in Athens: there were 400 of them in 1862.

Among the Germans who stayed behind, were those who had settled in Palio Heraklio, a village north of Athens. In 1837 king Otto founded the “military colony of Arakli”, by granting plots of land to sixty Bavarian ex-soldiers who were also expected to police the Athens countryside. Later on, some of them left Greece while some more “genuine” farmers from Germany took their place; at any rate, the population of Heraklio did not exceed 140 persons in 1912.

According to Belle, in 1870 “the agricultural colony of Heraklio didn’t prosper” and “most of its houses were abandoned” (Belle 1994: 78-79).

Eight years before, during the revolution against Otto, Heraklio was looted and its trees were cut; the village didn’t suffer such an attack during the revolution of 1843, yet a factory of two Bavarians in Ambelokipoi was torched then.

Nevertheless, Heraklio survived for many years as a place with a peculiar Bavarian character -although adulterated by marriages with Catholic people from Greece (Cyclades) and Italy and acculturated to the local environment. Visitors were always impressed by the gothic church of Saint Lucas (1842-45), and in 1912 the inhabitants of the village were described as generally “blond, redskin, blue-eyed”, with “strange German names”, dancing waltzes better than the Greek “syrtos” and maintaining their streets “very clean”. However, in their festivals they used to drink retsina wine instead of beer in big glasses, while only 2-3 old ladies spoke German. At any rate, an orthodox cemetery was founded in the village in 1936: Heraklio remained a centre of Attica’s Catholics, hosting their sole cemetery as well as Catholic monasteries [1] .

One of the purposes of the extensive discussion of the case of Heraklio was to illustrate that the European communities of Athens comprised not only bourgeois and professionals, but also labourers. Probably there weren’t that many farmers, but there are many testimonies about workers and artisans, particularly from Italy and Malta (Παρσάνογλου 2007, Ποταμιάνος 2011β). Εdmond About mentions 1.500 Maltese porters and day-labourers living in Athens and Piraeus in 1850 (Αμπού n.d., σ.70).

A wave of self-exiled revolutionaries from the defeated revolutions of 1848 arrived to Athens from all over Europe at that time. Many of them were artisans and continued to exercise their craft, such as the Italians who worked in the Greek silk industry. It seems that the majority of the Italian democrats and socialists settled in Patras and Corfu in significant numbers; however, some of them preferred Athens, where some other political refugees (Polish, French etc.) lived. Prominent among those international revolutionaries were Gustave Flourens, who later became one of the leaders of the Paris Commune in 1871, and Amilcare Cipriani, an anarchist who built barricades and raised a red flag in the area of Capnicarea during the 1862 revolution. Both of them joined the Garibaldian volunteers who fought in the Cretan revolt against the Ottoman Empire in 1866-69 (Δημητρίου 1985, Χατζηιωάννου 1985 και 1991, Chatzijoannou 1986, Καλλιβρετάκης 1998).

The novelist Papadiamantis, in one of his short stories, describes a company of Italian inhabitants of Athens meeting in a neighbourhood tavern; they comprised a builder, a carriage-maker, a seal-constructor and an itinerant musician; their atheism is a direct reference to the revolutionaries who had found refuge in Greece. In another short story, Papadiamantis speaks of an Italian partner of an ironing-woman in a working-class neighbourhood, who was working in Lavrio or in Isthmos, in Corinthos: here he refers to the next big wave of foreign workers in Greece, in the 1880s and 1890s. Skilled and unskilled workers came to work in big construction works such as the opening of the Corinth Canal and the construction of railways, as well as in the mines all over the country (Αγριαντώνη 1986, Παπαστεφανάκη 2017) some of them passed from Athens, or finally settled there.

An indication that part of the western European communities of Athens were poor, comes from the nature of the associations they founded. The “French society of mutual help in Greece” (1892), the German association “Philadelphia” (1898 -but actually we know that the club existed since the 1870s), the “Beneficial association of people from Austria-Hungary” (1907) and the “Italian society of mutual help in Attica” (1910) aimed particularly at assisting their compatriots who got sick. This was an aim that could be found exclusively at the statutes of labour unions and petit-bourgeois associations of that era -due to the lack of centrally-organized social insurance.

The poorer western Europeans included most artists who stayed for some months or years in Athens: Italian puppet-players, as well as German and Italian female singers and dancers who worked in the Athenian “cafe-chantants” that mushroomed at the end of the 19th century. The marriage of a 35 year-old Italian “magician” has been recorded in the Registry office of Athens in 1903.

In parallel to the artisans, the revolutionaries and the artists, a “migration of the elite” kept going on from other European countries and contributed to the population increase of the European communities of Athens in the second half of the 19th century. Architects such as Ziller, as well as less famous colleagues of him settled in Athens; together with engineers that staffed the Greek factories, mines and steamships; doctors, pharmacists and chemists; university and technical school professors; agronomists such as Heldreich, director of the university botanical gardens. Some of them became significant businessmen, such as the mineralogist Grohmann. Ofcourse the best known foreign entrepreneur in Athens was Serpieri, who exploited the mines of Lavrio.

Finally, there is also an intermediate social category: shopkeepers and master craftsmen, often successful and prosperous small businessmen, who introduced novelties in management and technology that had been developed in the other European countries, to the Greek capital. This happened particularly in the 1830s, when the first modern hotel in Athens was established by an Italian-Austrian couple; The founder of the coffee-shop “Oraia Hellas” that remained the centre of the Athenian life until the 1870s was Italian as well. The first tailors and textile merchants who established their shops outside the Old Market were also western Europeans (Ποταμιάνος 2011α).

In the beginning of the 20th century “novelties” in clothing were often associated with citizens of other European countries: in the commercial guides of Athens of 1899 and 1905 dressmakers and hatters were quite frequently foreign . A common pattern for shopkeepers with origins from western European countries was to deal with elite customers, that is with people who had shaped their taste and their consumption patterns through their contact withother European countries. Often shopkeepers of this kind advertised themselves as “providers of the Royal Court”, such as Schick’s “German bakery” on Stadiou Street.

A small survey of 21 marriages recorded in the Registry office of Athens in 1885-1888 completes the picture. The sample comprises marriages wherethe groom or the bride came from European countries excluding the Balkans (Table 1). Italians dominate the statistics: up to a point, this is a resultof the conjuncture of that time (many jobs in big construction works) -after 1902-1903 and 1911-1912 there is a bigger variety and the French become the biggest community. Interestingly, Italians prefer to marry to their compatriots, while the other foreigners marry Greek women. The factors that probably determined these choices included individual assessments about their permanent establishment in Greece; the presence of a community of compatriots which includes women; the proximity of their country and the feasibility of seeking a bride there. As regards men (unfortunately there isn’t any occupation recorded for women), engineers and clerk/private employees (probably in commerce) are the most frequently quoted occupations. There are also scientists, merchants and small manufacturers; workers are under-represented in our sample, but this also happens with Greek marriage records.

Table 1: Marriages recorded in the Registry office of Athens 1885-1888

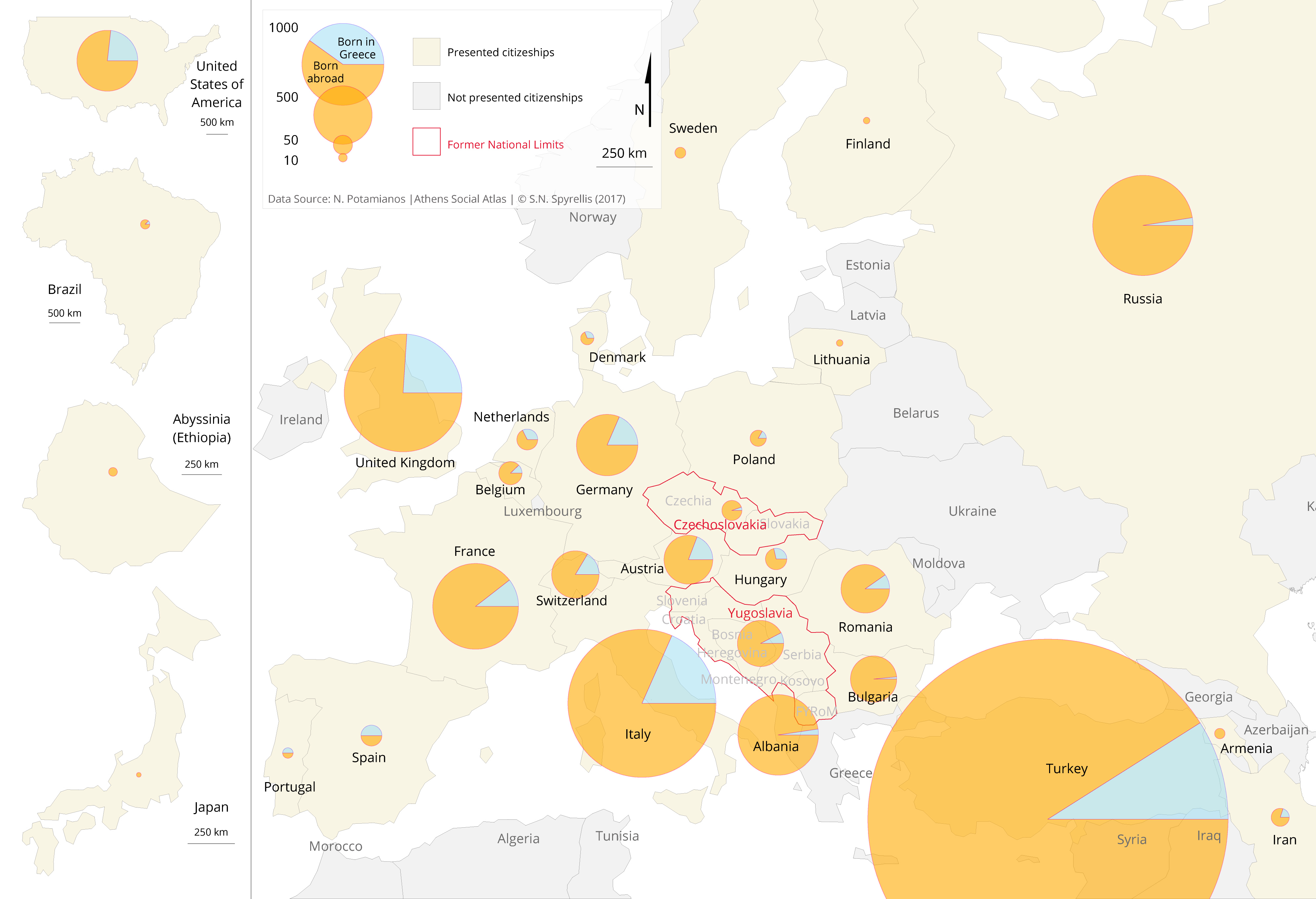

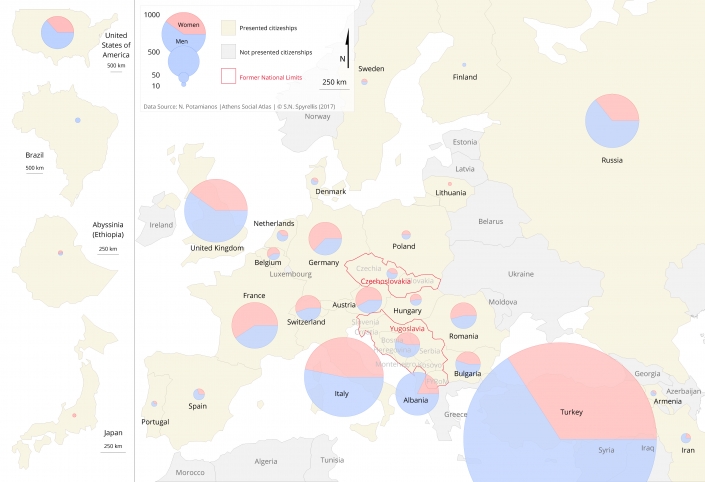

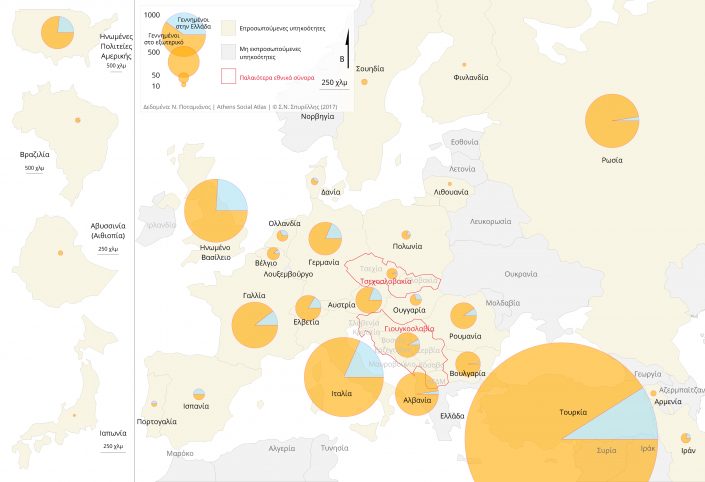

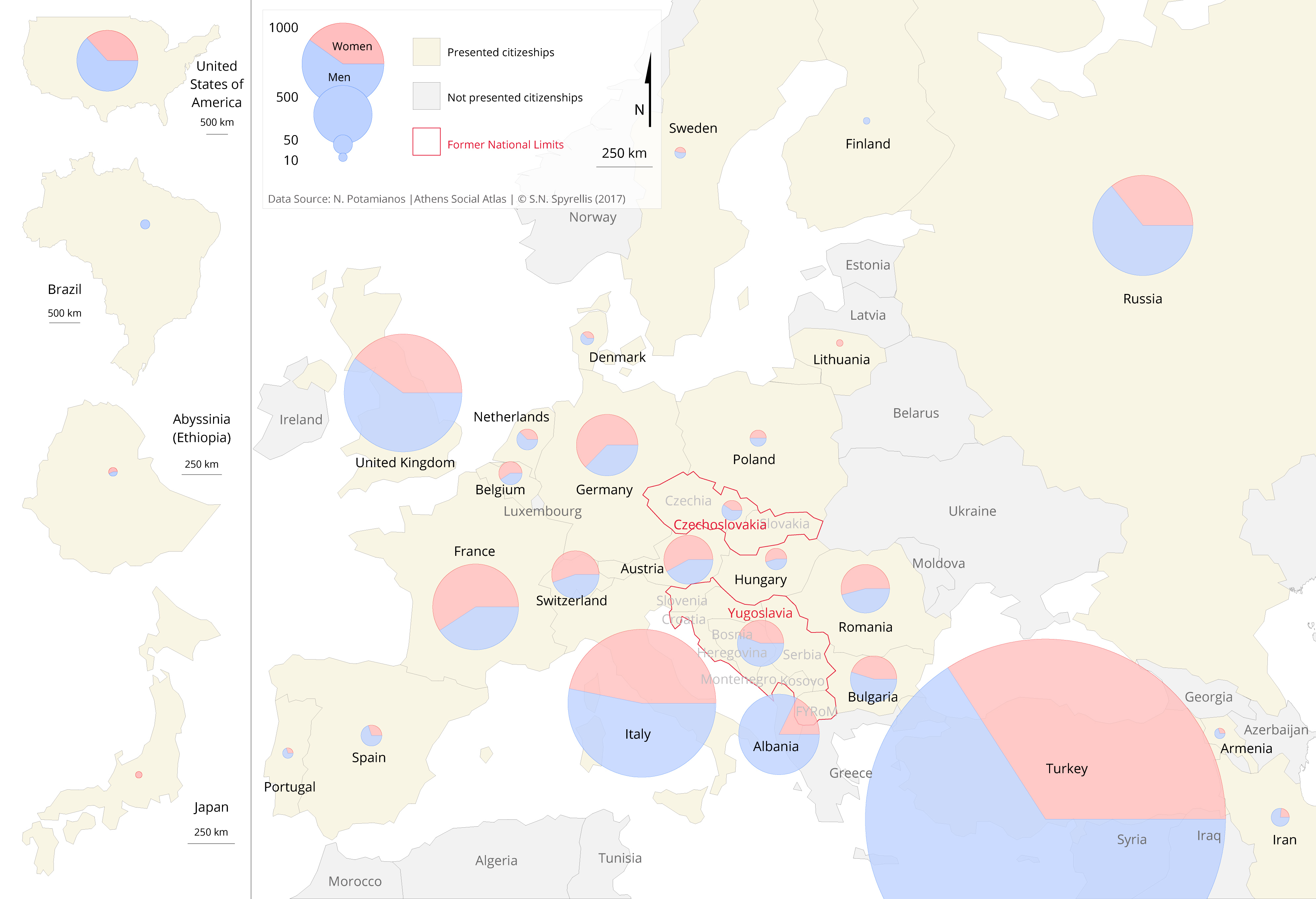

There isn’t any numerical evidence about the foreigner inhabitants of the municipality of Athens before the census of 1920 (Table 2). More than two thirds of foreigners come from Turkey and the Balkans, most of them obviously Greeks, either refugees from the wars of 1912-1922 or simply people who moved to Athens in search of a better fortune; many of the latter must have come to Athens much earlier. From those who were citizens of another European country, a third was Italian (among them Greeks from the Dodecanese). There was also a high percentage of British citizens: some of them must have been Cypriots -or Maltese. The quite high number Russians is due to the Russian revolution. The numbers of French, Germans, Austrians and Swisses probably include far fewer Greeks. There is a 10-25% of people from these nationalities who were born in Greece (while the Russians were evidently more recent immigrants). Finally, the gender composition of the communities is interesting. The 55-63% of the French, German, Austrian and Switch citizens are women, while in the total of the city’s foreign population there is only a 44% of women. It is possible that women working in professions less evident than dressmakers etc. were recorded in the sources used in this paper: domestic servants, nurses, teachers and artists.

Table 2: Foreigner inhabitants of the municipality of Athens, 1920

Map 1: Distribution of Foreigner inhabitants of the municipality of Athens, citizenship and sex

Map 2: Distribution of Foreigner inhabitants of the municipality of Athens, citizenship and place of birth

Let us finish this article by presenting some itineraries of the types of professions to which we have referred. Wepresent evidence about the lives of successful professionals, rather than the more famous Duchess of Piacenza or the pioneer brewer Karl Fix.

The furniture-maker Valentinos Steingässer (1844-1917) was born in Germany; he was evidently a relative of the Bavarian artisan of the same name who came to Athens during the reign of King Otto; besides Valentinos declared that his shop was established in 1836. In 1880 he bought a building near the church of Chrysospiliotissa, in the commercial centre of Athens, and he set up his workshop, his shop as well as his house there. Steingässer was very popular and well-respected among his peers He was elected for 15 years in the Board of the carpenters’ association and became their president in 1893. His son Antonis succeeded him in businessand he was also elected in the Board of the Carpenter’s Guild. “Steingässer and Son” had created a noteworthy business: they were advertised as “cabinet-makers of the Queen” and they employed 20 workers [2].

The Denoia family was another dynasty of cabinet-makers from Italy who reached at least three generations in the profession. Their ancestor Rafaele is mentioned in 1912 as an “excellent old furniture maker” who “taught many generations of artisans” -among them his son Antonis, who was also sent to Rome for three years to study cabinet-making. In 1899 the shop of “Rafael Denoia and Sons” was in Solonos street, in Neapolis. Antonis moved to the bourgeois neighbourhood of Kolonaki, where he also established a workshop -inherited by his son Rafael during the interwar years. Antonis closely collaborated with the decorator Rudolf Vavek, son of a Bavarian brewer who had settled in Otto’s kingdom. Rudolf lived in Kolonaki and was married to a Greek woman; he was probably the first decorator in Greece [3].

Francesco Rossi, an Italian from Bologna, was the first carriage-maker who upscaled his workshop to a big factory. Initially he worked in the factory of Feder, a German, and in 1861 he established his own workshop. His compatriot, Serpieri, supported him and soon the manufacture of Rossi in the old craftsmen neighbourhood of Metaxourgeio became the biggest business in carriage-making, employing 60 workers in 1912. Francesco was succeeded in 1890 by his three nephews, Ioakeim, Pavlos and Rafael, who were also skillful craftsmen. When Rafael married in 1888 with an Italian woman, he had learned to write Greek [4].

Of course Rossi is a common name and thus we detect various artisans with that name: Ludovico Rossi, who won a prize in 1870 Olympia for a table he constructed; [5] or the carpenter Spyro Rossi, who came to Athens from Corfu in the 1890s at the age of 20 or25; then married and worked as a salaried labourer in several carpenters’ workshops [6].

However, the best known Rossi in 1900 Athens was Raynoldos, an Italian with Greek mother and French citizenship; he found refuge in Athens in the 1890s, when he was persecuted by the French government for his political activities. In 1896 he was the orator in one of the demonstrations in Athens in support of the Cretan revolution. In 1909-10 he took an active part in the radical movement after the Goudi coup: in the summer of 1910 Rossi called for a “popular dictatorship” in one of his speeches and he was arrested by the police. He was arrested again in 1921, when delivering a speech in the Zappeio park about socialism, as he concluded by condemning the war that was then fought against Turkey. Another young communist remembers him as a “loony old man” who frequented the premises of the party and its newspaper in 1923 and who lied about being a foreign press correspondent. Actually, one day Rossi managed to be received by Plastiras, the dictator, who urgently needed to legitimize his policies in the eyes of European public opinion and diplomats. Plastiras was mostly interested in explaining why it was necessary to execute six prominent politicians of the royalist camp and he was very happy when the “journalist” approved of his actions; but then he heard Rossi proposing to execute Plastiras’ political mentor, Venizelos. Rossi ranted against Venizelos and did not stop even when Plastiras left him alone in the room (Σταυρίδης 1953:136).

[1] Γεωργίου Μαλτέζου, Το χρονικόν του Ηρακλείου Αττικής, Athens 1970, 57-64 and 109-111.

[2] Archive of the professional association of furniture makers of Athens: Proceedings of the board 1890-1907 and 18 July 1917, file 1904, Register book 1905-1912; Historical archive of the National Bank of Greece: Α 1 Σ 10 Υ 81 file 321; Archive of the Professional Chamber of Athens: Register book 1925; Γιώργος Παρμενίδης και Ευφροσύνη Ρούπα, Το αστικό έπιπλο στην Ελλάδα 1830-1940, Πανεπιστημιακές εκδόσεις ΕΜΠ, Athens 2003, 81, 176 and 189∙ Εμπρός 24 November 1908, Ακρόπολις 7 February 1912

[3] Archive of the professional association of furniture makers of Athens: file1904, Register book 1905-1912∙ Παρμενίδης και Ρούπα, Το αστικό έπιπλο, op.cit., 81, 129, 265 and 377∙ Ακρόπολις 7 and 18 February 1912.

[4] Registry Office of the Municipality of Athens: Book of marriages 1888∙ Νέα Εφημερίς 2 May 1890∙ Ακρόπολις 8-12 March 1912.

[5] Παρμενίδης και Ρούπα, Το αστικό έπιπλο, op.cit., 126.

[6] Archive of the professional association of furniture makers of Athens: Account of the Board for 1899-1900, file 1904, Register book 1905-1912.

Entry citation

Potamianos, N. (2017) Cosmopolitan Athens: the communities of Western Europeans in Athens in the 19th century, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/cosmopolitan-athens/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.79

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Belle H (1993) Ταξίδι στην Ελλάδα 1861-1874. Πυλαρινός Θ (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Κάτοπτρο.

- Seidl W (1984) Βαυαροί στην Ελλάδα. Αθήνα: Ελληνική Ευρωεκδοτική.

- Von Plȕskow W (2014) Ημερολόγιο. Available from: http://bussedocu.gr/ημερολογιο-πλυσκω/ (ημερομηνία πρόσβασης 11 Δεκέμβριος 2017).

- Αγριαντώνη Χ (1986) Οι απαρχές της εκβιομηχάνισης στην Ελλάδα τον 19ο αιώνα. Αθήνα: Εμπορική Τράπεζα της Ελλάδος – Ιστορικό Αρχείο.

- Αμπού Έ (1854) Η Ελλάδα Του Οθωνος. Η Σύγχρονη Ελλάδα. Βουρνάς Τ (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Αφοί Τολίδη.

- Δημητρίου Μ (1985) Το ελληνικό σοσιαλιστικό κίνημα. Αθήνα: Πλέθρον.

- Καλλιβρετάκης Λ (1988) Η ζωή και ο θάνατος του Γουσταύου Φλουράνς. Βουγιούκα Α (επιμ.), Αθήνα: ΜΙΕΤ.

- Λυτ Χ (1991) Στην Αθήνα του 1847-1848. Αθήνα: Ερμής.

- Μαλτέζος Γ (1970) Το χρονικόν του Ηρακλείου Αττικής. Αθήνα: Ανατολής.

- Μπουρνόβα Ε (2016) Οι κάτοικοι των Αθηνών, 1900-1960. Δημογραφία. Αθήνα: Εθνικό και Καποδιστριακό Πανεπιστήμιο Αθηνών, Εθνικό Κέντρο Τεκμηρίωσης. Available from: http://ebooks.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/econ/catalog/view/4/10/110-1.

- Παπαδιαμάντης Α (1985) Άπαντα. Τόμος Τέταρτος. Τριανταφυλλόπουλος Ν (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Δόμος.

- Παπαστεφανάκη Λ (2017) Η φλέβα της γης. Τα μεταλλεία της Ελλάδας, 19ος-20ός αιώνας. Αθήνα: Βιβλιόραμα.

- Παρμενίδης Γ και Ρούπα Ε (2003) Το αστικό έπιπλο στην Ελλάδα 1830-1940. Αθήνα: Πανεπιστημιακές εκδόσεις ΕΜΠ.

- Παρσάνογλου Δ (2007) Η μεταναστευτική κινητικότητα στον ελληνικό ιστορικο-κοινωνικό σχηματισμό. Στο: Ζώρας Κ και Μπαντιμαρούδης Φ (επιμ.), Η μεταναστευτική κινητικότητα στον ελληνικό ιστορικο-κοινωνικό σχηματισμό, Αθήνα, Κομοτηνή: Σάκκουλα, σσ 137–157.

- Ποταμιάνος Ν (2011 a) Η παραδοσιακή μικροαστική τάξη της Αθήνας. Βιοτέχνες και μαγαζάτορες 1880-1925. Πανεπιστήμιο Κρήτης. Available from: https://elocus.lib.uoc.gr/dlib/6/f/8/metadata-dlib-1330425501-380121-25886.tkl#.

- Ποταμιάνος Ν (2011 b) ‘Ντόπιο πράμα!’ Το αίτημα εθνικής προτίμησης και οι στρατηγικές ελέγχου της αγοράς εργασίας από τις εργατικές συλλογικότητες: Αθήνα και Πειραιάς 1890 – 1922. Τα Ιστορικά, Αθήνα 55: 283–322.

- Σταυρίδης Ε (1953) Τα παρασκήνια του ΚΚΕ από της ιδρύσεώς του μέχρι του συμμοριτοπολέμου. Αθήνα.

- Χατζηιωάννου ΜΧ (1985) 1848: Ο ελληνικός χώρος δέχεται τους Ιταλούς δημοκρατικούς. Στο: Ο Garibaldi και ο ιταλικός φιλελληνισμός τον 19ο αιώνα, Αθήνα, σσ 42–51.

- Χατζηιωάννου ΜΧ (1991) Η τύχη των πρώτων Ιταλών μεταξουργών στο ελληνικό κράτος. Μνήμων 13: 121–138. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10442/8492.

- Chatzijoannou MC (1986) La presenza degli Italiani nella Grecia indipendente. In: Risorgimento Greco e filelenismo Italiano, Roma: Del Sole, pp. 137–143.

- Hobhouse JC (1817) A Journey through Albania and other provinces of Turkey in Europe and Asia, to Constantinople, during the years 1809 and 1810. Philadelphia: M. Carey.