2019 | Jun

I.Metaxa’s government, the “4th August” regime which came to power in 1936, considered conflict in Europe to be a real possibility. Moreover they realized that the airplane was going to dominate the fields of battle and as a consequence urban bombardments (provoking mass casualties) were more than probable (Εθνική Ένωσις Αεροχημικής Προστασίας/ National Association for Aero-chemical Protection 1936). This scenario drove Metaxa’s regime to conceive and implement a vast project of Civil Protection (Βλάσσης 2013) , focusing on the construction of numerous air–raid shelters. Noteworthy are the diversities in the type and size of the shelters that ranged from narrow underground galleries or small chambers, to organized shelters of hundreds of square meters including hygiene infrastructure, water tanks, numerous chambers and auxiliary rooms (Κυρίμης 2017).

Photo 1: Exemplary shelter with WC and autonomous water tank

Mandatory construction of shelters in public places and key infrastructure (government buildings, ports, stations, industries, refineries and elsewhere) was enforced via emergency laws (Πετράκη 2014) .

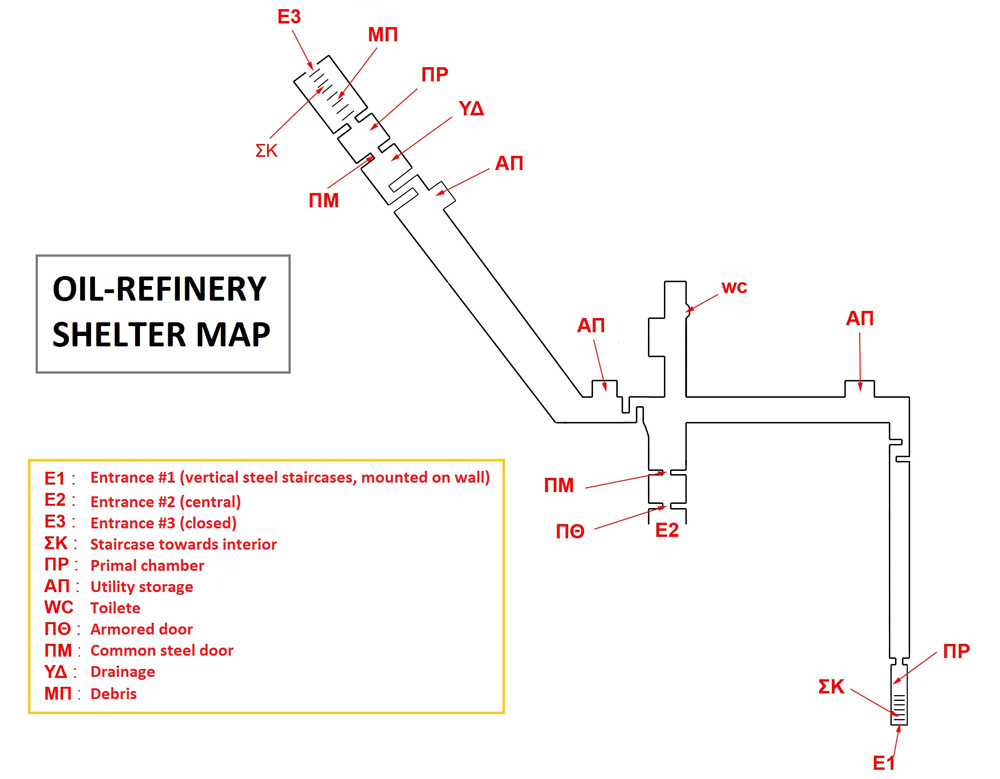

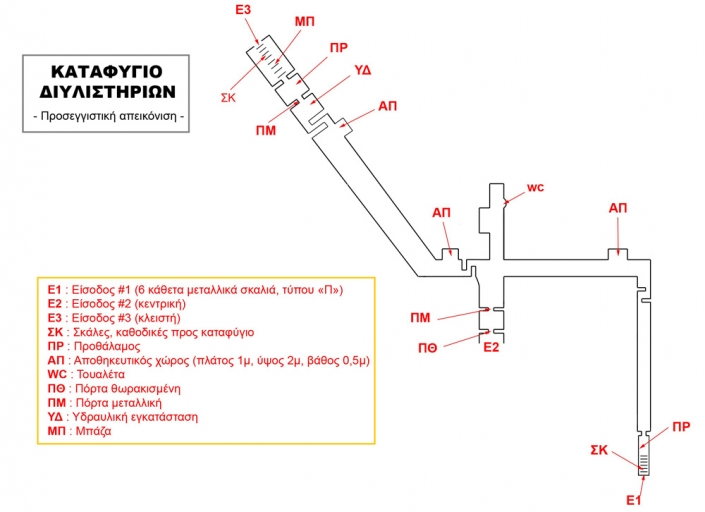

Photo 2: Refinery shelter plan

At the same time, the construction of a shelter was mandatory for every newly built building, of three floors or higher (ground floor included). Essentially, the submission of an air defense shelter plan and its approval was a prerequisite for issuing a building permit for any building (ΓΕΣ/ΔΙΣ Φάκελος 766/Β/11).

Photo 3 :A shelter in an apartment building in Kolonaki

Despite those measures, the shelters that were constructed were not enough to protect the entire population of Attica. Thus, many existing premises (underground buildings, mining galleries, caverns, ancient quarries, etc.) were reinforced and refurbished in shelters.

Photo 4: A tunnel carved into a rock-formation, used as a shelter

According to Field Marshal Papagos, during the period 1936-40, 400 public shelters were built in Attica, capable of protecting almost 40,000 people (Παπάγος 1997). At the same time, at least 5,000 private shelters were built, protecting several tens of thousands of citizens. With a small dose of exaggeration, we could claim that , “a city under the city” was built.

Photo 5: A shelter under a factory, partially filled with water

From a construction point of view, shelters were governed by a particularly strict regulatory framework («Τεχνικαί Οδηγίαι δια την μελέτην…» 1941). The competent state authority was the “Supreme Air Defense Administration” (SADA – ΑΔΑΑ in greek), which was staffed by both military (chiefly engineer officers) and civilian personnel (professors of the National Technical University of Athens and civil engineers). The regulations concerned all aspects of a shelter: the thickness of the walls, the building materials, the dimensions, the nature of the individual spaces, the layout, etc.

Photo 6: Underground corridor of a shelter

Each shelter was required to have an emergency exit on the opposite side of the main entrance. Through the emergency exit – and usually by opening a metallic hatch on the roof – it was possible to escape safely to the nearest outside space.

Photo 7: A typical emergency exit of a shelter

Another feature of the shelters of the era was the heavy armored doors, which sealed airtight and watertight. There were strict specifications for the shelter doors (door dimensions, metal densities, etc.). These specifications were compiled by the “Shelter Door Controlling Committee” (SDCC – ΕΕΔΚ in greek ) and were essentially a Greek version of the equivalent German specifications.

Photo 8: A heavy armored door

The problem with the strictness of these specifications was that until 1938 there was no industry in Greece that was capable of producing armored doors of such high standards. Thus, armored doors had to be imported from Germany. This led to the historic oxymoron, that the country which supplied Greece with means of protection, attacked her a few years later.

Photo 9: Armored door, built in Germany, in a shelter located near Syntagma square

Within a shelter, each person was entitled to an area of 0.8 square meters and a volume of 3 cubic meters. This space / volume allowed the person to stay in the shelter for 3 hours, subject to complete immobility. In case work had to be performed in a shelter, or the space was not enough for everyone, it was imperative to have a mechanical ventilation system installed.

Photo 10 : Going down the dark gallery of an 1938 shelter

Entering a shelter was a complex process. People first entered a small room, just after the entrance, which was officially called the “airlock”. From there, the healthy ones could go directly to one of the central chambers. On the contrary, those who had been affected by chemical gases, had to go through a special disinfection chamber before they were allowed to enter the inner shelter.

Photo 11: The main gallery of a shelter within the Electric Company

The sturdiest shelter in Athens was the one constructed in the building of the ” Army Share Fund Building / Megaro Metoxikou Tameiou Stratou (where the “Attica” department store is now housed). While the existing specifications defined 30 centimeters of reinforced concrete as the required wall thickness, the Army Share Fund Building shelter had 1-meter-thick walls. This did not escape the attention of the military , which used part of the shelter in order to house critical telecommunication services. Another emblematic shelter of the period was on the hill of Ardittos. It’s useful area was about 500 square meters and it had the largest central chamber throughout Attica (5 x 35 meters, height 5 meters). It could protect approx 1.300 persons.

Photo 12: Gallery in the shelter of Ardittos hill

As 1940 drew nearer, war preparations depleted raw materials and especially steel. As a result of these deficiencies, many shelters were reinforced structurally with various “patents”. A typical example of this practice, were shelters in railway stations, which were reinforced with old rails.

Photo 13: A shelter’s entrance, structurally reinforced with old rails

However, no infrastructure is sufficient without the intensive training of those who will use it.

The Metaxas regime took measures to educate and train the civilian population on air defense issues (Αντωνόπουλος 1940). The regime’s National Youth Organization ( Εθνική Οργάνωση Νεολαίας in greek and therefore known as EON) played an important role, its members regularly received relevant training (Μάνθος 1941) and performed air-defence functions (firefighting, removing debris, assisting the wounded, etc.). They also undertook the duty of distributing printed material regarding civil air-defence, on a door-to-door basis.

Photo 14: Emergency exit room of a shelter. The 7-meter-long staircase, leads onto Karageorgi Servias street

At the same time, the “Air Defense Communities” (Αγγελέας 1940) were instituted. They consisted of all persons who would resort to a particular shelter in case of need. Therefore, an “Air Defense Community” could be a family (in the case of a private shelter), the tenants of an apartment building (shelter of an apartment building), the residents in a neighborhood (public shelter) or all the workers in a factory (shelter of an important infrastructure). The leader of each Air Defence Community was called “Homeguard”.

Homeguards had to possess a range of virtues such as courage, good physical condition, education, composure and prestige. For someone to obtain the Homeguard title, it was compulsory to attend a special state-run “Homeguard school” where training lasted 1-4 weeks (depending on the size of the Air Defense Community). During peacetime, the Homeguard was charged with transferring his knowledge to the rest of the community and with keeping the shelter in good condition. During air-defence drills or wartime, he was responsible of opening the shelter, protecting the community and adhering to the regulations. A Homeguard was the official link between the Air Defence Department and his Air Defence Community. In each Air Defense Community, there was at least one deputy Homeguard. Only males of non-conscription age (17-19 or 45 and over) were chosen, in order to ensure that even in the event of general military mobilization, the Air Defence Community would not be deprived of its leader. The Homeguard was assisted in his duties by the “Home Fireman” and the “Home Nurse”, both with distinct duties (Γαλανάκης 1940).

Photo 15: Gallery in a shelter located near the National Garden

Nowadays, this “militarization” of the population seems terrifying. The possibility of civilian air-defence exercises in underground spaces and dark halls is a cause for concern. However, for the Athenians of that time, shelters were part of everyday life ( “Family Air Defense (Instructions for residents)” / «Οικογενειακή Αεράμυνα (οδηγίαι δια τους κατοίκους)» ,1938). Shelters were an opportunity for social mixing: people who did not previously know each other were required to cooperate during drills or to survive an air raid while stuck in a confined space. Athenians were so used to the shelters that Kostas Varnalis (1941) called them “shelterers” and wrote in a newspaper article : «Shelters –despite being underground, dark and sometimes humid- are places for vacations! In there, one may find many familiar, and even also unfamiliar, people. They get inside quietly, as if they are entering their own homes and take a seat. Most of them take out their newspaper and read it, to pass the time. Some ladies and girls, open their bags and grab something to knit, or read a novel. And when the siren signals the end of the alarm, nobody rushes to leave. Like a slow moving river, people of all ages, move towards the exit, slowly and formally, like people exiting from their own home. Because all “shelterers” feel that the shelter is their home».

Photo 16 : Chamber in a shelter located beneath an apartment building

After the start of the occupation, many shelters were taken over by the Germans and used as prisons. Structures that were built to provide Greeks with safety, became torture chambers. The buildings of 4 Korai Str. and 7 Zalokosta Str, are such cases. However, the occupation was not the last time that the shelters were used. They were meant to protect the people of Attica, once again. During the bombing of Pireaus by the Allies (11/1/1944) many civilians rushed again to the shelters (which they had not used since 1941) to save themselves. Also, just before 1945, shelters once more provided a safehaven for the Athenians, for one last time. The outbrake of the civil war (known as “Dekembriana”), forced many Athenians to seek protection in their familiar shelters.

Photo 17: Seeking protection quite a few meters below the earth

After WW2 was over, the usage of shelters was reduced significantly. Within a few years, developments in weaponry had rendered these structures obsolete. Most shelters were demolished, used as warehouses or disappeared under the subsequent construction. Nowadays, the remaining shelters are literally under our feet. Unfamiliar with them, we rush daily, passing over them, ignoring their existence and their history. They hide their historical footprint discreetly and reveal the signs of their existence only to the “initiated” observers.

Photo 18: A seemingly innocent lid in the pavement, is the emergency-exit of an old shelter

Despite their gradual disappearance, the shelters managed to capture the collective subconscious of the Athenians (even those who had never visited them). Forgotten, subterranean, dark, and sometimes labyrinthine places, they fuelledthe imagination, which gave rise to many Urban Myths. The stories of people entering an old underground shelter and – by crossing endless galleries – exiting to some other place in Athens, were quite widespread. According to the worldview of the supporters of the so-called “Secret Underground Attica”, many shelters communicated with each other, but also with the Parliament, the National Garden, the cave of Penteli and other places.

However, on-site historical research has shown that all these were merely myths (Κυρίμης 2015).

Shelters had finite dimensions and did not communicate either with each other or with any other location. However, this was not a reason to remove the “mysterious aura” which, to a certain extent, justifiably surrounded those places.

Photo 19: Emergency exit of a shelter. Mythical places and Urban Legends

The obsolescence of shelters does not imply their simultaneous historical depreciation. In other European cities, such structures have been renovated and wereopened to the public. Athens, a city with hundreds of shelters, refrains from such initiatives. It would be very positive if one shelter could be preserved and turned it into a “vehicle” that will take visitors to troubled (but very interesting) times, which were an important part of Greece’s modern history.

Photo 20: Entering an underground air-defence shelter, located under a popular railway station

Acknowledgements :

All the photographs in this article have been captured during personal visits to these shelters. Many of them have been taken by my dear friends and colleagues John Arseniadis and Marios Michailos, both of whom I would like to publically thank, for their assistance and support.

Entry citation

Kyrimis, K. (2019) Athens’ air-raid shelters 1936-40, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/athens-air-raid-shelters-1936-40/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.90

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Αγγελέας Ν (1940) Η Οργάνωσις της Παθητικής Αεραμύνης. Αθήνα.

- Αντωνόπουλος Δ (1940) Οδηγίαι παθητικής αεραμύνης, δια το προσωπικόν της Τραπέζης Αθηνών. Αθήναι: Τράπεζα Αθηνών.

- Βάρναλης Κ (1941) Καταφύγια. Πρωία, Αθήνα, 11η Απριλίου.

- Βλάσσης Κ (2013) Οι εξοπλισμοί της Ελλάδος, 1936-1940. Δούρειος Ίππος.

- Γαλανάκης Γ (1940) Η προστασία του αμάχου πληθυσμού από τας αεροπορικάς επιδρομάς. Η Νεολαία 40(91).

- ΓΕΣ / ΔΙΣ (χ.χ.) Περι επεκτάσεως των μέτρων κατασκευής καταφυγίων αεραμύνης εις υπαρχούσας πολυορόφους οικοδομάς. Αθήνα 766(Β): 11.

- Εθνική Ένωσις Αεροχημικής Προστασίας (επιμ.) (1936) Γενικαί Αρχαί δια την άμυναν του πληθυσμού – Αυτοπροστασία. Αθήνα.

- Κυρίμης Κ (2015) Τα Καταφύγια της Αττικής: Μια περιήγηση στη μυστική, υπόγεια Αττική. Αθήνα.

- Κυρίμης Κ (2017) Τα Καταφύγια της Αττικής: Συνεχίζοντας την περιήγηση στη μυστική, υπόγεια Αττική. Αθήνα.

- Μάνθος Ν (1941) Ο Φαλαγγίτης εις το καθήκον και εις την αεράμυναν. Αθήνα: ΕΟΝ.

- Μπακόπουλος Κ (1938) Οικογενειακή Αεράμυνα (Οδηγίαι δια τους κατοίκους). Αθήναι: Ανωτέρα Διοίκησης Αντιαεροπορικής Αμύνης της χώρας.

- Παπάγος Α (1945) Ο Ελληνικός Στρατός και η προς Πόλεµον Προπαρασκευή του από Αυγούστου 1923 µέχρις Οκτωβρίου 1940. Αθήνα.

- Πετράκη Μ (2014) 1940 – Ο άγνωστος πόλεμος – Η ελληνιστική πολεμική προσπάθεια στα μετόπισθεν. Αθήνα: Πατάκης.

- Τεχνικά Χρονικά (1941) Τεχνικαί Οδηγίαι δια την μελέτην και κατασκευήν αντιαεροπορικών καταφυγίων. 1(221–222): 86–96.