The geography of the ‘ESTIA’ accommodation program for asylum seekers in Athens

Papatzani Eva

Ethnic Groups, Housing, Planning

2020 | Mar

A series of scattered programs targeting asylum seekers and refugees have been planned and implemented by various actors in the urban space of Athens, following the arrivals of large numbers of refugees from 2015 onward. These programs, directly or indirectly affect aspects of the socio-spatial settlement of asylum seekers and refugees in the city, raising questions about the informal trends and the institutional actions that concern interethnic cohabitation at the local level.

This paper addresses the socio-spatial dimension and the geography of the ‘ESTIA’ accommodation program for asylum seekers in Athens. This dimension was not explicitly and publicly documented during the planning stage of the program. It is selectively explored in this paper by analyzing a) the placement criteria of ESTIA units (apartments and buildings) in the urban fabric and b) the discourse of competent bodies and their perceptions concerning ethnic diversity, dispersal and socio-spatial segregation in Athens. The paper also addresses the planning framework for ESTIA, driven by notions of “emergency” and “integration”, as well as the importance of associated urban actions.. These aspects of the analysis relate to interethnic interaction in the city and correspond to theoretical perceptions of urban studies that regard interethnic cohabitation as a process inextricably interdependent with place. They also re-introduce to the debate crucial questions on ethnic diversity, socio-spatial mix and segregation.

The research is part of the author’s doctoral thesis and it was conducted through the analysis of relevant legislation, systematic mapping of policies, collection, processing and mapping of quantitative data and qualitative semi-structured interviews with representatives of key stakeholders.

Introduction

The settlement of immigrant populations in Greek cities affected their urban development and social geography. Especially from the 1990s onwards, newly arrived populations settled by their own means, in the absence of relevant housing policies and integration planning. Migrant groups from Eastern Europe and the Balkans (1990s), as well as more recently arrived groups from the Middle East, Asia and Africa (mid-2000s) settled in central neighborhoods of Athens, making use of the available housing stock that was left behind since the partial moving of middle and upper-class locals to the suburbs from the 1970s onwards (Βαΐου κ.ά. 2007, Μαλούτας 2018). This settlement pattern produced a geography defined by socio-spatial mix and ethnic diversity, differentiated from the Northern American and Northern European cities that are defined by higher levels of ethno-racial segregation (Arapoglou 2006). In the case of Athens, horizontal housing segregation decreased and the conditions of spatial proximity that prevailed, formed the ground for interethnic cohabitation and the development of informal trends towards immigrants’ “integration” [1] (Leontidou 1990, Βαΐου κ.ά. 2007, Αράπογλου κ.ά. 2009).

Crucial questions on the settlement of refugees and asylum seekers in cities have been raised in literature. A series of studies discuss urban housing policies for refugees at the local level and the importance of placement methods of the accommodation units in cities (Doomernik and Glorius 2016, Eckardt 2018, Seethaler-Wari 2018), Some authors have also provided critical reviews of refugee settlement dispersal policies in urban space, which were implemented in some countries aiming to decrease housing segregation (Musterd et al. 1997, Andersson 2003, Netto 2011, Darling 2017). Policies for ethnic diversity and interethnic mixing in specific local contexts have also been discussed (Arapoglou 2012), as well as issues of everyday life, interethnic relationships and boundaries (Jacobsen 2006). Perspectives vary over time, from viewing ethnic diversity as a barrier to social cohesion (Putnam 2007) to understanding it as a positive factor that should be reinforced (Vertovec 2007), Other views emphasize the intersections of diversity and socio-economic inequality (Arapoglou 2012).

From 2015 onwards, due to the increased arrivals of refugee populations in Greece, a series of scattered programs and actions targeting refugees and asylum seekers have been planned and implemented by various actors (Local Government, NGOs, International Organizations) in the urban space of Athens. These programs relate (directly or indirectly) to dimensions of the socio-spatial settlement of refugees and asylum seekers in the city, raising questions about both the informal trends and the institutional actions that concern interethnic cohabitation at the local level. This paper addresses the socio-spatial dimensions and the geography of the ‘ESTIA’ accommodation program for asylum seekers in Athens. Despite the fact that these dimensions were not explicitly and publicly documented during the planning stage of the program, they are selectively explored in this paper by analyzing a) the location selection criteria of ESTIA units (apartments and buildings) in the urban fabric and b) the discourse of competent bodies and their perceptions concerning ethnic diversity, dispersal and socio-spatial segregation in Athens. The paper also addresses the planning framework for ESTIA which was driven by notions of “emergency” and “integration”, as well as the importance of urban actions carried out.. These aspects of the analysis relate to facets of interethnic interaction in the city and correspond to theoretical perceptions of urban studies that regard interethnic cohabitation as a process inextricably interdependent with place. They also bring back to the debate crucial questions on ethnic diversity, socio-spatial mix and segregation.

In terms of methodology, the research was conducted through the study of relevant legislation, systematic cataloguing of policies, collection, processing and mapping of quantitative data and qualitative semi-structured interviews with representatives of key stakeholders, namely the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Local Authorities and several Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) [2].

The geography of ESTIA programme and the competent bodies’ perceptions of ethnic diversity, dispersal and socio-spatial segregation in Athens

The UNHCR’s ESTIA program, started in mid-2016, as a programme for ‘Emergency Support to Integration and Accommodation’ [3] and it benefits asylum seekers who meet certain vulnerability [4] criteria, as well as applicants for family reunification. The programme provides the beneficiaries with urban accommodation, whether in apartments or in other buildings. The Ministerial Decision of 2019 defines ESTIA as a “program providing financial assistance and housing” aiming to “ensure an adequate standard of living for applicants for international protection by providing cash assistance and to ensure their safe accommodation, as appropriate, and the provision of support services […]” [5]. UNHCR is implementing the program through partnerships with 11 municipalities and 12 national and international NGOs (UNHCR 2019). Despite the fact that ESTIA seems concerned with the “integration” of asylum seekers, as proclaimed in its initial official title, it actually functions primarily under the “emergency” governmentality framework. Thus, it maintains its temporary character until today, reproducing a permanent state of precariousness (Kourachanis 2018)[6].

“UNHCR is here just for capacity-building, we are here to assist during the emergency. When everything is set up, we move out. […] Integration is the government’s responsibility. This is very important to us, we do not do integration, UNHCR does not engage in implementation of integration, we support integration” (UNHCR representative).

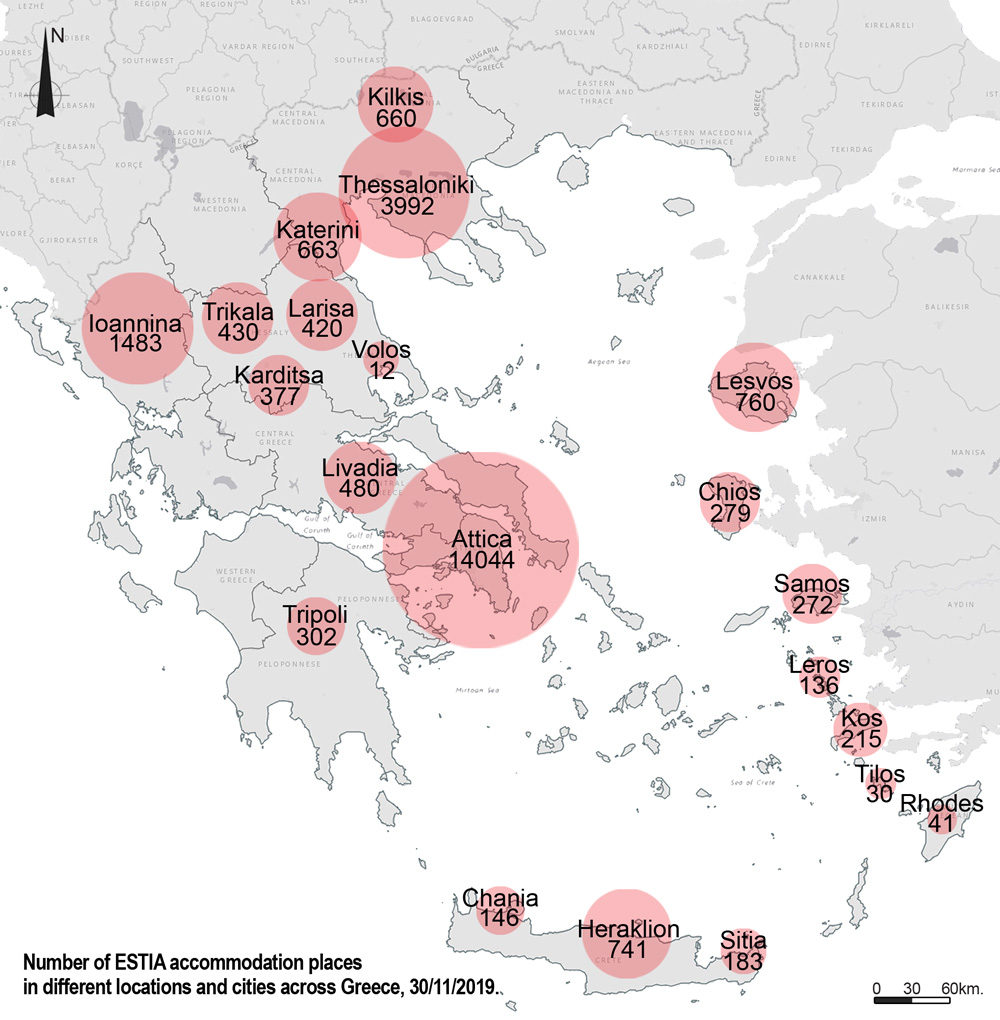

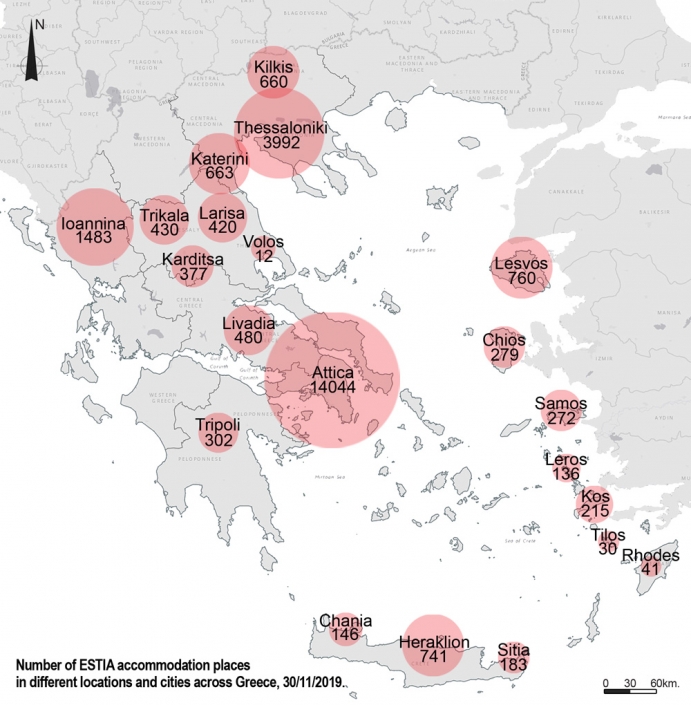

The ESTIA accommodation program is implemented inside the urban fabric of Greek cities. This is in contrast to the location decisions concerning the open Temporary Reception and Accommodation Facilities for asylum seekers (ie Camps) in the mainland (which are usually established away from the urban fabric) and the Reception and Identification Centres (ie Hotspots) in Northeastern Aegean islands (who are concerned with the “geographical restriction” of asylum seekers). As of November 2019, 4.501 apartments and 14 buildings were rented in 14 cities and 7 islands across Greece. Accommodation capacity had reached 25.666 places [7] and 21.639 people were accommodated (UNHCR 2019, UNHCR 2020). The geography of the program across Greece, shows for a concentration of 55% in the Attica Region, followed by Northern Greece (20,7%), Central Greece (7,8%), the islands (6,5%), Western Greece (6%) and the island of Crete (4%) (UNHCR 2020).

Map 1: Number of ESTIA accommodation places in different locations and cities across Greece, 30/11/2019

Source: UNHCR (2019) ESTIA, 2019

Concerning the process of choosing the apartments to rent, the program defines certain official criteria [8]. During the initial stage of the program, the need to find a big number of accommodation places as fast as possible led to the rental of whole buildings, especially in the center of Athens (buildings that were empty until then).

“There was the accommodation demand and each apartment we rent can accommodate a maximum of 6 people, so we started searching for larger facilities, like hotels and buildings. As soon as we found a whole building, we could then shelter almost 400 people immediately” (UNHCR representative).

ESTIA expanded through renting apartments in blocks of flats, while gradually the rental of whole buildings was reduced by the decision of UNHCR. Dispersal of accommodation places in apartments across the city was determined as best practice due to the high costs of maintaining the rented buildings and because the programme aimed to spread the economic benefits of renting to a larger number of property owners. Today, 95% of the total facilities are apartments while 5% consists of entire buildings (UNHCR 2020).

With respect to the location choices of ESTIA apartments in Athens, the interviews with competent bodies reveal certain criteria which could be grouped into two different categories: The criteria for apartment blocks (according to which, the goal was to rent a limited number of apartments in each block) and the criteria for neighborhoods. The initial goal, a political decision of Athens Municipality, was to disperse rented apartments in various areas and avoid the concentration of asylum seekers’ settlement in specific central neighborhoods of Athens, in order to avoid the “dangers of ghettoization”, a term that emerges in the discourse of key stakeholders.

“When we first launched the program in 2016, we had set very strict criteria. For example we refrained from renting more than one apartment in each building. We wanted to avoid ghettoization, we didn’t wish for everybody to end up in Victoria or Omonia. Unfortunately, when you are desperate, these criteria tend to relax. So right now, there are certain areas with higher concentrations than others. […] I mean we go wherever there is supply” (UNHCR representative).

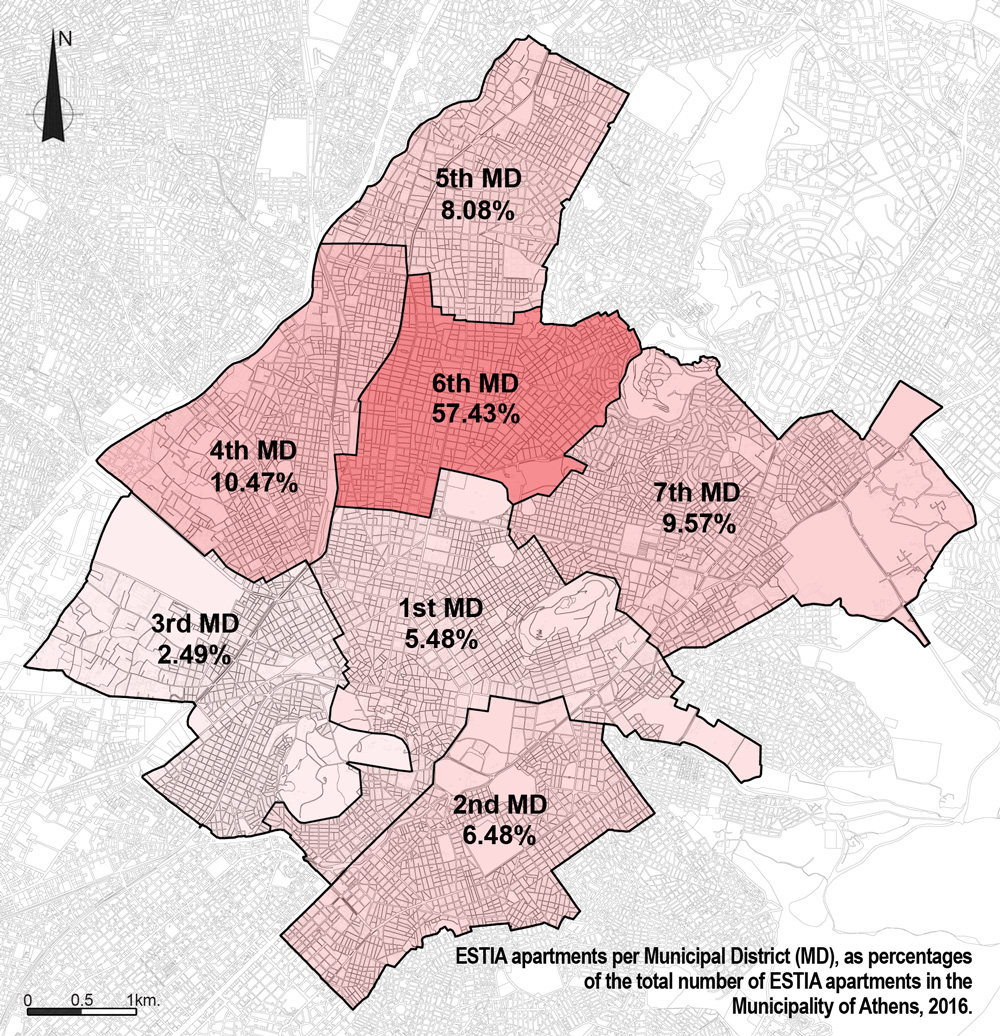

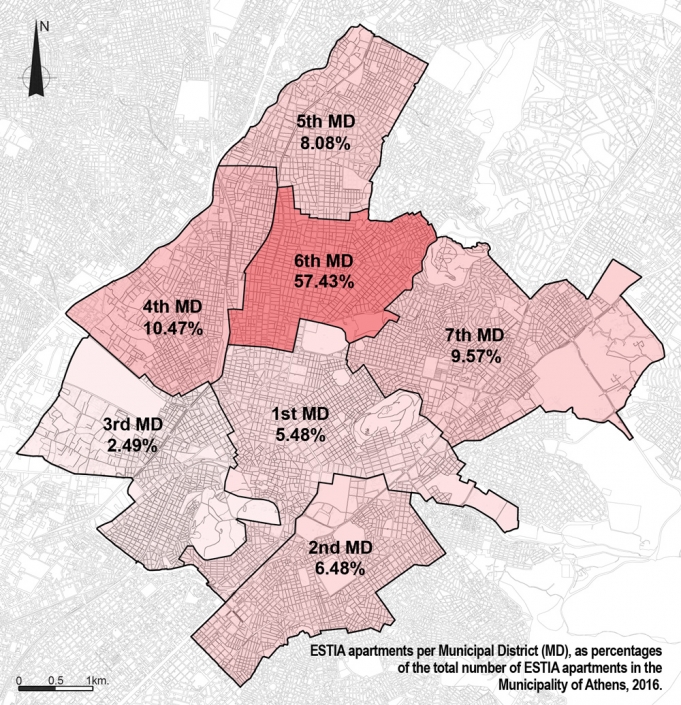

Nevertheless, the main supply of apartments for rent was found in lower-income neighborhoods of central Athens, where small property owners made their apartments available because of the financial security provided by ESTIA. Meanwhile, these areas (e.g. around Acharnon and Patision streets) are have a relatively higher concentration of immigrants, coming from various ethnic backgrounds and different periods of migration, as recorded already in the 2011 census [9]. Thus, overall, notwithstanding the general dispersal principle of ESTIA apartments in Athens Municipality and neighboring municipalities (e.g. Zografou, Nea Smirni, Moschato-Tavros, Nea Philadelphia-Chalkidona and others), higher numbers of ESTIA apartments were to be found in certain Municipal Districts of Athens, as presented in Map 2.

“What we have strived for since the beginning, is to avoid areas that already host a large migrant population. We tried – and largely succeeded – to disperse our apartments in Athens through co-operating with adjacent municipalities. Of course, the supply was very big in areas where many immigrants already live – so we have accommodation places also there, but we have really tried to achieve dispersal” (Local Administration representative, partner of ESTIA).

Map 2: ESTIA apartments per Municipal District, as percentages of the total number of ESTIA apartments in the Municipality of Athens, 2016

Source: Παπαγιαννάκης (2017)

The geography of ESTIA appears to adjust to the existing ethnic geography of the city, where locals, immigrants and refugees live in spatial proximity. Key stakeholder perceptions of ethnic diversity, dispersal and inter-ethnic cohabitation emerge in their discourse. Ethnic diversity is perceived as a positive element that can serve interethnic cohabitation in the city and should be promoted.

“The local economy, apartments, I think they all contribute to diversity and social tolerance towards difference. […] I personally believe that diversity makes society stronger and I think that accepting someone who fled war in your neighborhood is a sign of strength. It’s certainly not a weakness” (NGO representative, partner of ESTIA).

Despite adopting such a discourse on diversity, the planning principles of ESTIA aimed at the dispersal of apartments for asylum seekers in different neighborhoods, avoiding their “over-concentration” in neighborhoods where immigrant populations were already settled. As such, the increase of ethnic concentration in certain neighborhoods (that were considered to be overburdened) was avoided. Thus, the positive conceptualization of diversity seems to contradict an implicit negative perception of the concentration of refugees and immigrants, which is often misidentified with “ghettoization” in the discourse of key stakeholders.

At the same time, during the implementation stage of the program, certain cases of density of ESTIA apartments’ placement were created, as well as relatively higher concentrations of asylum seekers in neighborhoods where migrant populations were already settled. Competent bodies evaluate this outcome as negative, identifying it with the threat of “ghettoization”. Yet such a correlation is misguided. The geography of ESTIA, which adheres to the geography of the ethnic mix in Athens (consisting of neighborhoods where no single immigrant ethnic group constitutes a majority), cannot be identified with policies of asylum seeker segregation in urban space. On the contrary, what emerges is a reinforcement of “hyper-diversity” (Alexandri et al. 2017) in certain neighborhoods, a development that can be evaluated as mostly positive for the everyday life of different ethnic groups. Besides, dispersal of refugee populations and social mixing are not sufficient as unique guiding principles of urban policies. On the contrary, they should be attended by practices and actions supporting long-term socio-spatial settlement and interethnic cohabitation at a local level.

Graph 1: Percentages of ESTIA program beneficiaries by nationality, 30/11/2019

Source: UNHCR (2019) ESTIA,2019

Unresolved questions for interethnic cohabitation

“Hyper-diversity”, limited housing segregation and spatial proximity that characterize ESTIA’s geography, do not necessarily guarantee “social proximity” or harmonious interethnic cohabitation. On the contrary, serious differences exist between superficial contacts with “difference” and “the others” in the city – as they are usually promoted by urban policies – and more sustained inter-ethnic interactions (Valentine 2008, Koutrolikou 2012). While “refugee training workshops on daily life in the city” (UNHCR 2018), were organized in the framework of ESTIA, they were mostly voluntary from the part of each ESTIA partner, and they mainly involved cultural events as is usual practice in social mixing policies. Such event-based interaction can facilitate a basic level of familiarization with “the others”, but “its temporary character is not sufficient for building relations or resolving existing tensions” (Koutrolikou 2012: 2062).

The importance of this debate is even more crucial regarding the urban space of Athens, where the increased likelihood of “contact” between immigrants and locals has already been highlighted (Kandylis and Maloutas 2018). Ethnic diversity, spatial proximity, social mix, everyday “contact” and the limited horizontal ethnic segregation in Athens are necessary but not (uniquely) sufficient conditions for achieving interethnic cohabitation. Yet, they provide a fertile ground for a future planning of the necessary policies for the refugees’ socio-spatial settlement, especially in view of the gradual transmission of ESTIA’s management to the Greek authorities. The absence of a more comprehensive policy for interethnic cohabitation (one connected to the accommodation scheme) and the simultaneous existence of a variety of other, fragmented, temporary and voluntary actions create a specific contradiction which can (re)produce peculiar forms of exclusion, social bounding and conflicts in urban space.

[1] The concept of integration remains a complex one, despite multiple efforts to provide an appropriate definition. See e.g. the definition proposed by Ager and Strang (2008), who include housing and social connections – among others – in the list of factors that contribute in integration. In this paper, usage of the term is avoided for various reasons, amongst which certain aspects of the criticism it had received (see also Mavrommatis 2018, Schinkel 2018). Usage of the term “socio-spatial settlement” is preferred, as it gives prominence to space as a factor capable to highlight complex socio-spatial aspects of “integration”, which are frequently overlooked.

[2] The research was conducted during the academic year 2017-2018 and it was part of the author’s doctoral ongoing thesis with the original title: “Migration, diversity and negotiations of cohabitation at the neighborhoods of Athens. Institutional policies and everyday practices”. The PhD thesis has been supported with scholarships from the Special Account for Research of the National Technical University of Athens (NTUA) and then from the General Secretariat for Research and Technology (GSRT) and Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (HFRI) under the “HFRI PhD Fellowship grant” (GA. no. 1192).

[3] ESTIA is an evolved form of ‘UNHCR Accommodation for Relocation Project’, which was launched in October 2015 and completed in September 2017.

[4] As defined in Law no. 4375/2016 and Law no. 4540/2018.

[5] Government Gazette 853/B/12.03.2019. Ministerial Decision 6382/19: Establishment of a Regulatory Framework for the program of provision of cash assistance and accommodation “ESTIA”.

[6] Such precariousness was intensified by the aforementioned Ministerial Decision, according to which recognized beneficiaries of international protection were required to leave their ESTIA apartments before the beginning of the next “integration” step (Program “Helios”) and without an efficient connection between the two programs.

[7] Each apartment can host a maximum of 6 accommodation places.

[8] Architectural design criteria, concerning the apartments’ size, their situation, sunlight and ventilation, home appliance etc. Apartment rental is agreed between the owner and each ESTIA partner. There is a 400 euro limit to the rent price and some rents are frequently pre-paid to the owner.

[9] For a review and mapping of these concentrations based on 2011 census data, see Balampanidis (2019).

Entry citation

Papatzani, E. (2020) The geography of the ‘ESTIA’ accommodation program for asylum seekers in Athens, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/the-geography-of-the-estia-accommodation-program/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.95

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Αράπογλου Β, Καβουλάκος Κ-Ι, Κανδύλης Γ, κ.ά. (2009) Η νέα κοινωνική γεωγραφία της Αθήνας: μετανάστευση, ποικιλότητα και σύγκρουση. Σύγχρονα Θέματα 107: 57–67.

- Βαΐου Ν (2007) Διαπλεκόμενες καθημερινότητες και χωρο-κοινωνικές μεταβολές στην πόλη. Μετανάστριες και ντόπιες στις γειτονιές της Αθήνας. Καραλή Α και Γρέβια Κ (επιμ.). Αθήνα: ΕΜΠ, L-Press.

- Μαλούτας Θ (2018) Η κοινωνική γεωγραφία της Αθήνας. Κοινωνικές ομάδες και δομημένο περιβάλλον σε μια νοτιοευρωπαϊκή μητρόπολη. Αθήνα: Αλεξάνδρεια.

- Παπαγιαννάκης Λ (2017) Απάντηση σε ερώτημα επιτροπής κατοίκων της Αθήνας. Θέμα: Πρόγραμμα στέγασης προσφύγων του Δήμου Αθηναίων σε συνεργασία με την Ύπατη Αρμοστεία. Αθήνα.

- Ager A and Strang A (2008) Understanding integration: A conceptual framework. Journal of refugee studies 21(2). Oxford University Press: 166–191.

- Alexandri G, Balampanidis D, Souliotis G, et al. (2017) Divercities: Dealing with Urban Diversity-The case of Athens. Athens: ΕΚΚΕ.

- Andersson R (2003) Settlement Dispersal of Immigrants and Refugees in Europe: Policy and Outcomes. Vancouver: Vancouver Centre of Excellence.

- Arapoglou V (2006) Immigration, segregation and urban development in Athens: the relevance of the LA debate for Southern European metropolises. Επιθεώρηση Κοινωνικών Ερευνών 121(C): 11–38.

- Arapoglou V (2012) Diversity, inequality and urban change. European Urban and Regional Studies 19(3). Sage Publications Sage UK: London, England: 223–237.

- Balampanidis D (2019) Housing Pathways of Immigrants in the City of Athens: From Homelessness to Homeownership. Considering Contextual Factors and Human Agency. Housing, Theory and Society. Taylor & Francis: 1–21. DOI: 10.1080/14036096.2019.1600016.

- Darling J (2017) Forced migration and the city: Irregularity, informality and the politics of presence. Progress in Human Geography 41(2). Sage London: 178–198.

- Doomernik J and Glorius B (2016) Refugee migration and local demarcations: New insight into European localities. Journal of Refugee Studies 29(4): 429–439.

- Eckardt F (2018) European Cities Planning for Asylum. Urban Planning 3(4). PRT: 61–63.

- Jacobsen K (2006) Refugees and asylum seekers in urban areas: a livelihoods perspective. Journal of Refugee Studies 19(3). Oxford University Press: 273–286.

- Kandylis G and Maloutas T (2018) From laissez-faire to the camp: Immigration and the changing models of affordable housing provision in Athens. In: Bargelli E and Heitkamp T (eds) New Developments in Southern European Housing after the Crisis. Pisa: Pisa University Press, pp. 127–154.

- Kourachanis N (2018) From camps to social integration? Social housing interventions for asylum seekers in Greece. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 39(3–4). Emerald Publishing Limited: 221–234.

- Koutrolikou P-P (2012) Spatialities of ethnocultural relations in multicultural East London: discourses of interaction and social mix. Urban studies 49(10). SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England: 2049–2066.

- Leontidou L (1990) The Mediterranean City in Transition: Social Change and Urban Development. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mavrommatis G (2018) Grasping the meaning of integration in an era of (forced) mobility: Εthnographic insights from an informal refugee camp. Mobilities 13(6). Taylor & Francis: 861–875.

- Musterd S, Ostendorf W and Breebaart M (1997) Segregation in European cities: patterns and policies. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 88(2). KNAG : 182–187.

- Netto G (2011) Strangers in the city: Addressing challenges to the protection, housing and settlement of refugees. International Journal of Housing Policy 11(3). Taylor & Francis: 285–303.

- Putnam RD (2007) E pluribus unum: Diversity and community in the twenty‐first century the 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian political studies 30(2). Wiley Online Library: 137–174.

- Schinkel W (2018) Against ‘immigrant integration’: for an end to neocolonial knowledge production. Comparative migration studies 6(1). Springer: 31. DOI: 10.1186/s40878-018-0095-1.

- Seethaler-Wari S (2018) Urban planning for the integration of refugees: The importance of local factors. Urban Planning 3(4). PRT: 141–155.

- UNHCR (2018) ΕΣΤΙΑ. Διήμερο ενημερωτικό σεμινάριο για τους πρόσφυγες του προγράμματος ΕΣΤΙΑ στη Νέα Φιλαδέλφεια. Available at: https://bit.ly/2YSg4qg (ηaccessed 4 January 2020).

- UNHCR (2020) ΕΣΤΙΑ.Στατιστικά Στοιχεία. Available at: http://estia.unhcr.gr/el/home_page/ (accessed 4 January 2020).

- UNHCR (2019) ΕΣΤΙΑ. Ενημερωτικό σημείωμα για τη στέγαση. Available at: https://bit.ly/2QICrfG (accessed 4 January 2020).

- Valentine G (2008) Living with difference: reflections on geographies of encounter. Progress in human geography 32(3). Sage Publications Sage UK: London, England: 323–337.

- Vertovec S (2007) Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and racial studies 30(6). Taylor & Francis: 1024–1054.