2020 | Mar

Electric scooters have made their appearance lately in Athens, welcomed, much like in other Greek cities, with a praising discourse on behalf of the journalists and local authorities (Αθηναϊκό-Μακεδονικό Πρακτορείο Ειδήσεων, 2019 / Η Εφημερίδα των Συντακτών, 2019 / TyposThes, 2019) as the new, hyped alternative green transportation proposal, incorporating smoothly in the city [1].

Such reports do not constitute a public debate on the city, but rather an uncritical acceptance of Western modernism, highlighted by the indifference concerning the city’s public space organization. It is the result of a peculiar urban public silence Athenians and their authorities share for decades, as they seem to mutually find refuge in the interests of larger or smaller scale appropriation of public space. With this text we attempt to present a critical perspective towards this new transportation means, with the ultimate goal to defend public space.

Considering electric scooters, we have to clarify the distinction between the private ones and those of public use, as are rented floats. Setting momentarily aside the rental version, private use scooters transport solution is very similar to that of a motorcycle. What they have in common is they both are different versions of a two-wheel motor vehicle. Their difference consists mainly of the following:

- Electric scooters are lighter and smaller than the smallest motorcycle. This means the private ones can be parked inside buildings.

- They are electrically powered rather than with gasoline, which causes no pollutants released into the urban atmosphere and environment.

- Scooters have smaller wheels than motorcycles, which makes them less stable and thus more dangerous, consequently resulting in many of their users driving them improperly along the sidewalks for safety reasons. While motorbikes are already causing significant trouble to pedestrians and city mobility today by simply being parked on pavements, scooters go as far as to move on them, thus aggravating furthermore the situation.

- In addition, the lack of stability on scooters provide, comparing to motorbikes, limits their using ability within a significantly younger population.

- An electric scooter has a lower purchase price than a motorbike and does not require a driving license and security, but it is a vehicle of less energy autonomy and slower mobility speed.

However, electric scooters owe their success in their public version, rather than their private one. This suggests that, practically, scooters can (and tend to) function as an intermediate transportation means from or towards a public transport one, or even a private car. In that sense, scooter limits the use of private cars, thus rendering public transport a “friendlier” means of transportation.

Undoubtedly, the above-mentioned provides an interesting technical argument for those to promote this novelty. However, under this very perspective, it would be more (or, at least, equally) reasonable for journalists, politicians and transport professionals to promote the solution of public bicycles (also western induced) that electric scooters tend to replace. Though, before analyzing this transition from bicycles to scooters, we must first oppose the argument that Athens is unsuitable for bicycle use due to its uneven terrain, by simply reminding that bikes also come in a hybrid version, combining a motor engine along with their traditional pedomobile system [2].

Since the 1990s, the European Union has been promoting the compact city model on urban planning (Commission of the European Communities 1990). The concept of the compact city is based on the theoretical idea that a denser urban structure is along with mixed use zones would reduce the population’s mobility needs (Neuman 2005). However, denser structures are even less friendly towards private cars, due to their spatial limitations (Melia, Parkhurst & Barton 2011). As a result, the concept of “sustainable mobility” was created. The first version of this plan has been promoting private car’s use and space consumption limitation, while simultaneously developing the extent of public transport and non-motorized means of transportation (i.e. walking and biking). In this context, public bicycle systems with fixed parking spots were designed, anchoring to a series of special urban installations, formerly cars’ parking lots. Subsequently, hybrid bikes were introduced in order to cover all potential terrain formations and age sets. Those systems, installed from Paris to Mexico City, are the result of a low-cost public investment with a design intending on a smaller environmental footprint.

In the neoliberal framework, the design of non-motorized transport was left (or even led) into the hands of private initiative, resulting in risking every beneficial effect of the original “sustainable mobility” plan concerning the environment and the physical condition of residents. In terms of design, firstly the anchoring system was replaced by a GPS search solution, which led to scooters end up being parked on the sidewalks. Secondly, scooter was preferred over the hybrid bike, which is a more expensive product, due to the complexity of its construction, while also relatively difficult to handle, due to its weight and size. This resulted in the elimination of the “pedomobile” possibility. Furthermore, the aforementioned abandoning of the anchoring system has also induced an additional environmental consequence: Public-service vehicle systems are not self-regulating; that originates from either the uneven terrain, or from a variety of other reasons, including the unstable weather conditions, and results in vehicles tending to accumulate in specific parts of the city. The task of balancing the system is then undertaken by motor trucks or private cars, charged with the redistribution of bicycles or scooters throughout the city. So, while this procedure is a simple station to station transfer in the case of the anchoring system , in the GPS solution case vehicles must be collected from random locations over the whole city, which causes an additional need for recharging upon their return to the selected spots, thus significantly increasing the overall environmental footprint of the system function.

In conclusion, instead of protecting and increasing pedestrian and non-motorized space according to the original, environmentally friendly design, we end up with the pedestrian and bicycle areas of the city being used up as motorways and parking lots by the very transportation means that was meant to preserve them.

Photo 1: Electric scooters parked on the pavement, blocking pedestrian pass-through. Vasilissis Sofias Avenue, Athens, August 2019

In Greece, much like the case worldwide, this absurdity is currently undergoing the process of establishing rules, which only effectiveness in practice can be demonstrated in areas where an extensive network of bike lanes is available. The conditions of urban mobility networks in Athens being what they are, upcoming Greek legislation can only lead users either to the dangers of the roadway use, or to the illegal use of pavements. In effect, that is, it is merely a legal management of potential accidents, rather than preventing legislation (Παπαδημητράκη 2019).

One last result, though perhaps the most characteristic of the essence of the issue, provoked by this transition from bicycle to scooter, is that the cost for the user has skyrocketed. In Paris, for example, public bicycle usage sums up to a cost of €3.10 per month for normal bikes and €8.30 for hybrid ones (Velib Metropole 2019), while scooters are offered for the same rate as in Athens, that is for a fee of €1 per drive, plus €0.15 per minute use (Lime 2018, Hive 2019). It can be easily therefore understood, that we face a less socially fair concept of transport planning, which, to the degree that it leads to the limitation of other alternatives, additionally stands as an urban gentrification factor.

The initial infiltration of electric scooters is mainly due to their use by young tourists, as well as their ability to cover relatively short urban routes that, until recently, could only be served by taxis. Thus, a growth mentality for specific financial interests and urban behaviors is been created; interests and behaviors that, in the long run, much like AIRB’N’B or UBER, may evolve into modifiers of overall urban structures and flows.

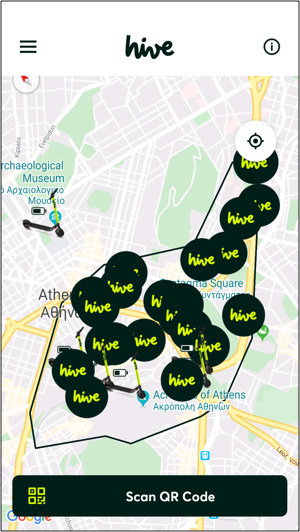

Photo 2: Hive electric scooters company’s development area in Athens. Plan of an initial development based on tourist routes

Source: Hive Application, November 4, 2019, 18:13 (GMT + 2)

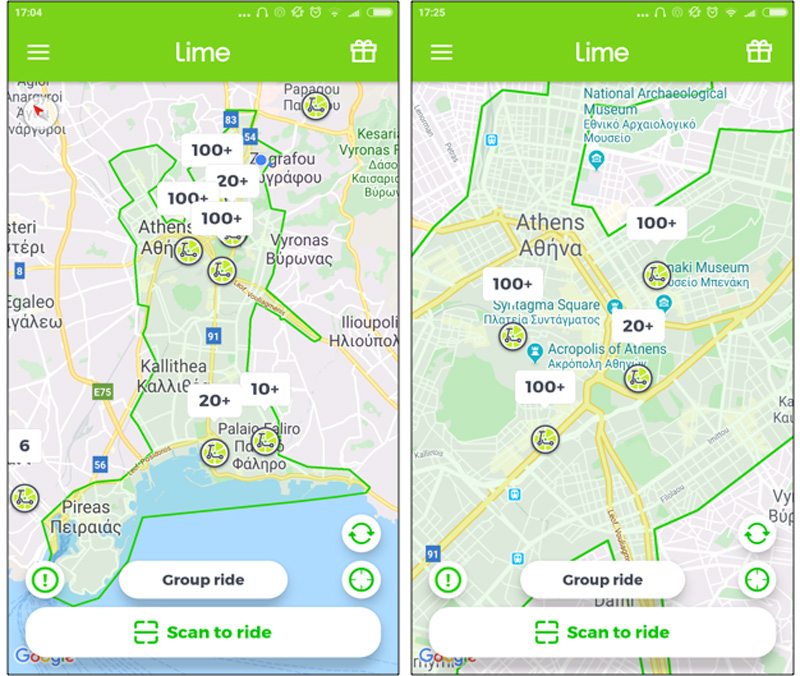

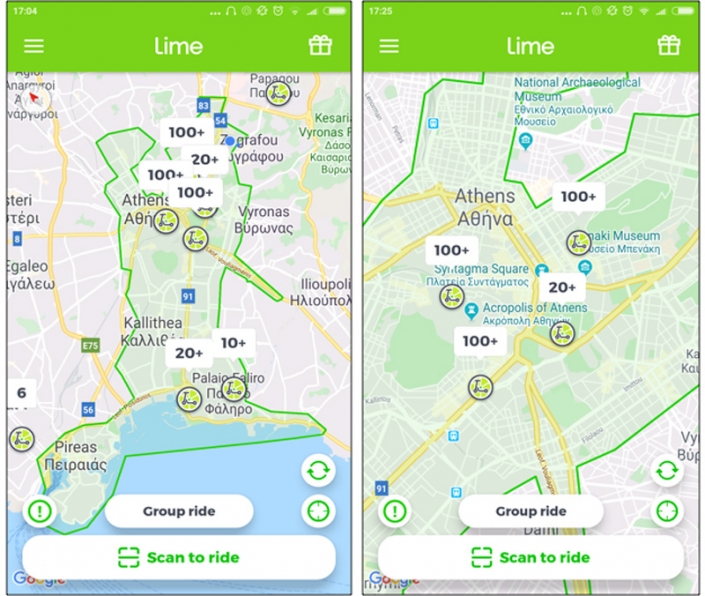

Photo 3: Lime electric scooters company’s development area in Athens. Extensive development plan; the exclusion of Exarchia neighborhood is characteristic

Source: Lime Application 4 November 2019, 17:04 & 17:25 (GMT+2)

While neoliberal innovations are known to promote everything but the social justice, it is nevertheless worth asking oneself why it is that in Greece, concerning city matters, planning is not at least obliged to confront with its fairer and environmentally friendlier versions. The answer to this question is partly linked with the Greek economic crisis, but it is also related to the general lack of respect for public space. Thus, urban planners along with their political court benefit directly by promoting gentrification innovations, in search of a land values gain. At the same time, they avoid to increase state participation in transportation, while also bypass collisions with the self-interest of automobilists.

Perhaps the most important issue concerning electric scooters is how we will avoid accidents, even fatal ones, with a legislation that is being blind to the lack of the appropriate infrastructure. Given though the global tendency to redesign cities by gentrification and social segregation practices, the most characteristic amongst such cases being that of the city of London, Athens inhabitants have to revise their aforementioned silence towards public space policies, should they want to preserve their city’s democratic profile against any planning seeking to separate Athens urban space into a city for the poor and a city of the rich.

[1] No doubt, this does not suggest they can actually be considered a “green means”, partly because the electricity they consume may come from Ptolemais lignite combustion (a highly carcinogenic process), as well as because 95% of out-powered lithium batteries will end up, due to economic viability reasons, as toxic waste under non-urban terrain. Apparently, the same ecological debate also applies to electric cars (Jacoby 2019).

[2] Charging is achieved through the electric network as long as through a pedal-dynamo.

Entry citation

Tzanetatos, D. (2020) Athens: electric scooters, a critical approach, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/athens-electric-scooters-a-critical-approach/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.94

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Commission of the European Communities (1990) Green paper on the urban environment. Brussels: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Melia S, Parkhurst G and Barton H (2011) The paradox of intensification. Transport Policy 18(1). Elsevier: 46–52.

- Neuman M (2005) The compact city fallacy. Journal of planning education and research 25(1). Sage Publications: 11–26.

Online sources:

- Αθηναϊκό-Μακεδονικό Πρακτορείο Ειδήσεων (2019) Τα ηλεκτρικά πατίνια της Lime ήρθαν και στο Δήμο της Αθήνας. Available at: https://www.amna.gr/home/article/326997/Ta-ilektrika-patinia-tis-Lime-irthan-kai-sto-Dimo-tis-Athinas (accessed 4 February 2020).

- Η Εφημερίδα των Συντακτών (2019) «Έρχονται» τα ηλεκτρικά πατίνια στο Ρέθυμνο. Available at: https://www.efsyn.gr/efkriti/koinonia/202463_erhontai-ta-ilektrika-patinia-sto-rethymno (accessed 4 February 2020).

- Παπαδημητράκη Μ (2019) Στραβοτιμονιές στην πόλη. Σχεδία 75: 34–38.

- Hive (2019) Δες πώς δουλεύει. Εύκολο, σωστά? Available at: https://www.ridehive.com/home-gr#how-it-works-gr (accessed 4 November 2019).

- Lime (2018) Electric Scooters in Paris: Lime Rolls Into World’s Tourism Capital. Available at: https://www.li.me/second-street/electric-scooters-in-paris-lime-rolls-into-world-tourism-capital (accessed 4 November 2019).

- TyposThes (2019) «Σαρώνουν» τα ηλεκτρικά πατίνια – Δωρεάν για τα «γενέθλια». Available at: https://www.typosthes.gr/thessaloniki/203558_thessaloniki-saronoyn-ta-ilektrika-patinia-dorean-gia-ta-genethlia (accessed 4 February 2020).

- Jacoby M (2019) It’s Time to get Serious about Recycling Lithium-Ion Batteries. Chemical & Engeeniring News 97: 1–3. Available at: https://cen.acs.org/materials/energy-storage/time-serious-recycling-lithium/97/i28.

- Velib Metropole (2019) Les abonnements pour les utilisateurs réguliers. Available at: https://www.velib-metropole.fr/offers (accessed 4 November 2019).