Pangrati in the 50s, Elvis Presley and Anna from Petralona. Topoi and my topi

2024 | Jul

Pangrati in the 50s

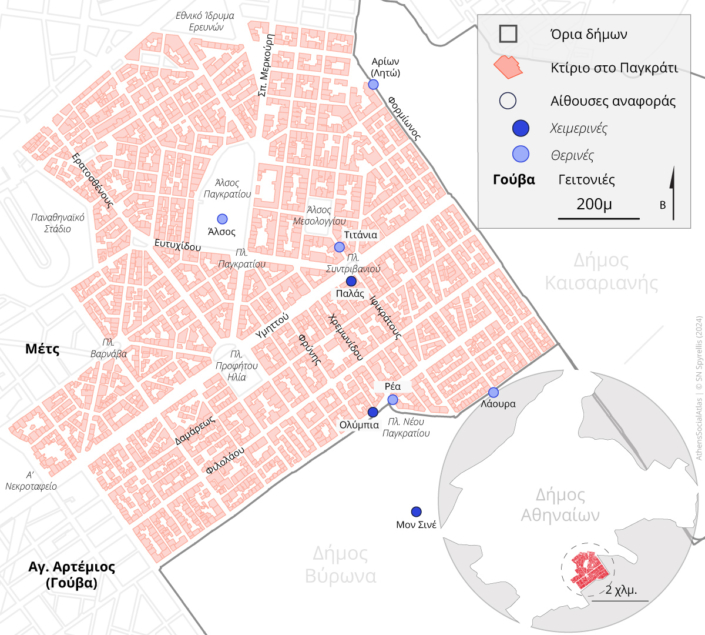

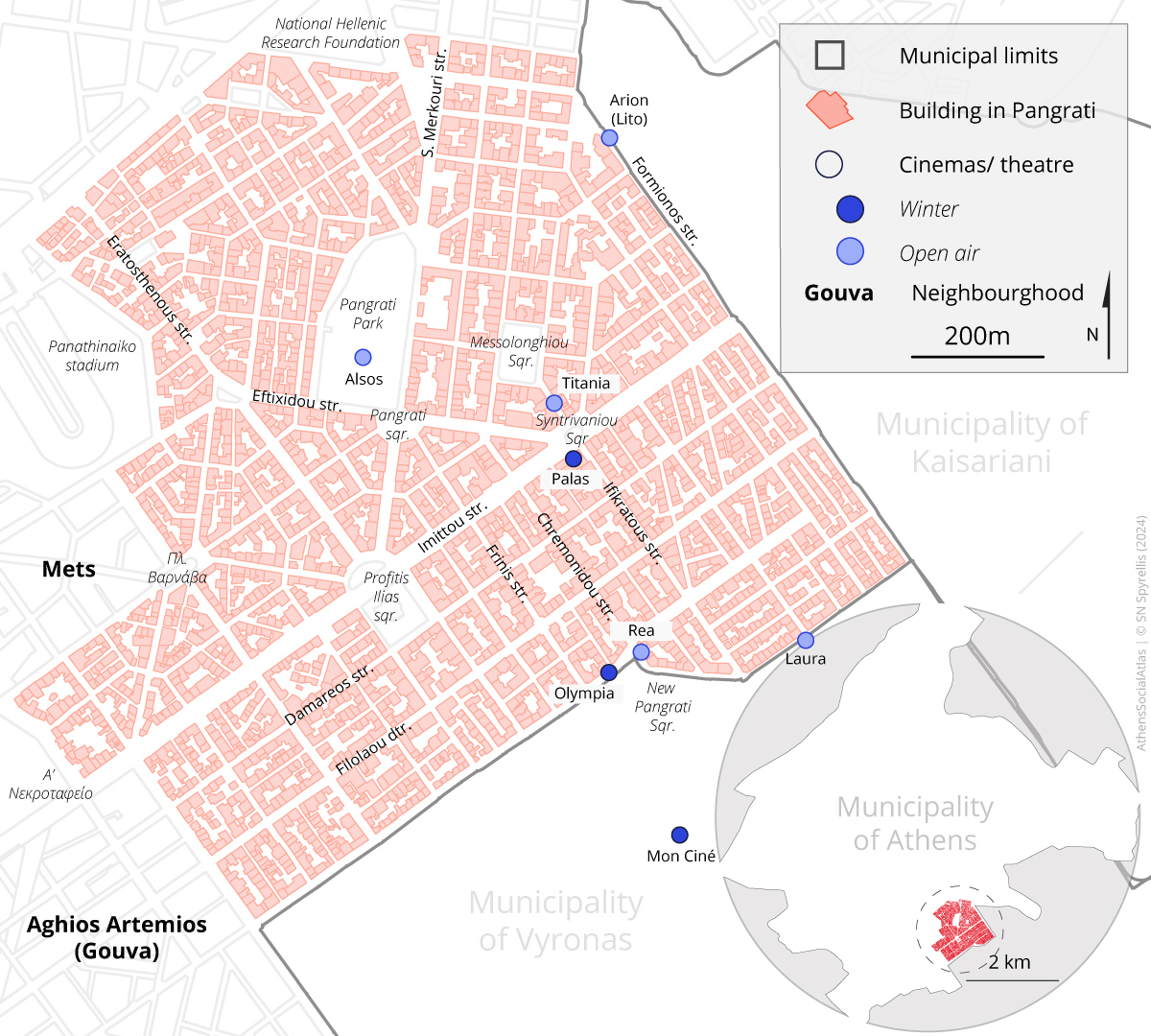

The neighborhood of Pangrati became familiar to Athenians because of the Tram line No 2 “Kypseli- Pangrati”, a green tram with a melodic bell. Its eastward trajectory ended in Pangrati square, the square of Palas cinema [1], that came to be known as the “Old Terminal”, when, far later, Vyronas (Byron’s) Bridge was designated as the “New Terminal” for buses, renaming the area to Neo Pangrati. It was there that in 1956 the second winter cinema of the neighborhood, the Olympia, appeared. A little higher up, where the area of Vyronas [2], begins, was the famous Mon Ciné, with long benches on its last rows, often a venue for theatre groups and sometimes conjurers to perform before screenings.

Photo 1: Tram no 2 passing in front of Panathinaiko Stadium

On the contrary summer cinemas were numerous apart from the Palas, that operated as both closed and open-air. There was the Alsos, inside the well-known Pangrati Park -that emulated the Royal Garden with bears in cave-like cages and duck ponds-, next to the garden theatre of the same name that hosted musical programmes with singing talents and where, during the junta, the Free Theatre Group [Elefthero Theatro] courageously produced political satire plays, debuting with the unforgettable “And You’re Combing your Hair”. There was the Titania in Messolonghiou Square, the Arion on Formionos Street, soon renamed Aria and then redesigned as Leto, the Rhea, almost opposite the Olympia on New Pangrati Square, the Laura that still remains, maybe others I cannot recall that operated before the 60s.

Map 1: The Pangrati neighbourghood

Ymittou and Eftychidou were the main streets in Pangrati; they converged on the square where, beneath Potaga’s cinema, the imposing cafe Thalassinos fronted Kotrotsos’ restaurant, next to the real estate office of Tzanoulinos and Son, who spent most of the day sunning themselves as, with the exception of a few rental deals in autumn, business was slow in those times. Close to the square was the famous Scanatovitch photographers’ studio, with provoking at that time pictures of aspiring starlets in its front window wich also rented out national and carnival costumes for vatious events or sittings. Queen Amalia and Evzone costumes sporting authentic bust ornaments were the most popular of all.

Map 2: Theatres and cinemas in Pangrati

Ymittou Street paved up until it reached Frynis street, was the main lieu of Sunday bride markets. It then continued as a dirt road, up towards the rocky area of Profitis Ilias at the top, from where we’d gaze out to the sea. “One day”, grownups use to say, “there will be a road going straight to Faliro and we will take it and go bathing”. For quite a few years however, the only bathing and diving was the wild splashing of little boys in a “pool” beneath the church -forbidden to girls. On this steep uphill part of the “avenue”, apart from the amazing July Church fête with its towering wheel, boat-swings and glittering trinkets, there were showings by an itinerant municipal cinema we called the Demos’ Cinema. The sparse automobile traffic came to a halt, children and adults sat on the ground, grandparents used the stools they used in church and we watched Greek films, newsreels and american cartoons, munching on roasted chickpeas and sunflower seeds, with the smell of acetylene coming from the seller’s lamp surrounding us.

Map 3: Pagrati on the E. Curtius & J.A. Kaupert (1895-1903). Acropolis and Profitis Ilias (Elias) can be seen

The tram was a great source of entertainment for kids. As soon as it emptied we would pile into it and, ignoring the ticket collector’s anger, flip over the seat-backs, as the tram was moving back- and- forth to its starting point. Older boys used tram rails to straighten and flatten the nails they needed to make Karagkioz figures they designed and cut out from the blank backside of Marshall Plan posters. Best of all was their famous “skalomaria”: perched on the tram’s steps, bumpers, cable cleats they would go down Eratosthenous slope until they reached Ilissos bridge and the Stadium and then climbed back up to be greeted by furious scoldings [3].

Photo 2: Ilissos flowing in front of the Panathinaiko Stadium

The Stadium and Ilissos, up to the actual location of the Hilton, then known as Vrysaki, were the Pangrati’s western boundaries. Themain road leading there was Spyrou Merkouri, lined by decent houses and hovels that had escaped expropriation, with huge fig-trees, mulberry trees, lemon trees and palm trees in their gardens. Somewhere behind the actual Caravel hotel I remember Anna Fonsou’s father’s green grocery often scolded by my grandmother, a customer of his, for having a picture of a bikini clad beauty in his shop -his beautiful engenue daughter’s photo-, instead of the Virgin’s icon. Beyond the Ilissos, laid the Palace, the Royal Garden, and the Zappeion, for sunny walks with the parents. To the north, on the bed and the banks of the filthy stream that the erstwhile river had been reduced to, lay the refugee shanty town that we would cross over by little wooden bridges, as we went to our pediatrician somewhere close to Mavili Square or to the still remaining St Helen’s clinic [4]. From Vrysaki and higher up, Formionos street was the boundary with Kaisariani. On the corner of Ymittou and Formionos was the café Poseidon with narghiles for the elderly refugees of both neighborhoods. A little further up on Formionos was the hammam where every Saturday we’d follow a group of merry ladies -small boys were allowed in- carrying towels, clogs and snacks for a whole enjoyable morning.

Photo 3: Tram no 3 crossing the Syntagma Square

We called the area beyond Varnava square “at the Cemetery” more often than Mets. We called “Parko”, Messolonghiou square with the Titania cinema and the ridge above it, where the Organization of Rehabilitation of the Disabled stands today, “Little Mountain”. That was where we would go for walks on sunny winter days with the school. Other such day trips took us to Analipsi (Ascension), Metamorfosi (Transfiguration of Christ), Zoodochos Pigi [5] and the furthest, most adventurous to St. Zohn Kareas – near-empty, sparsely populated areas at the time, with shady groves around their churches. That is where we were taught all about condoms, in urchins’ vocabulary. From Profitis Ilias ridge, going down Filolaou and Damareos streets, lined with houses with yards and little gardens we’d reach Gouva, renamed St Artemios, an area snubbed by the soi-disant topnotch Pangrati dwellers, but much sought after by the girls, because of the cool guys of “Club 13”, as we called the 13th all-male High School. This slanting part of Filolaou street was a valley-like road lined on the right and mostly on the left towards Kopana-Vyronas by abrupt ridges and goat trails with refugee houses, or rather rooms clustered around a common courtyard, with shared outhouses, makeshift cesspits and open sewers, flowing down the slopes. The smell was widespread, unvarying -and unforgettable. Sheep pens, beehives and quarries (one of which has become the Melina Mercouri-Anna Synodinou open-air theatre), were visible on the then wide, sparsely populated grazing area of the western foothills of Mt Ymittos. Flocks and mainly itinerant milk and yogurt sellers would come down to Pangrati and their cries would resonate at dusk, “Sheep’s yogurt, the yogurt maker”. They were the night sellers. In daytime, there were many other itinerant vendors: quilt-makers, umbrella repairers, tinkers, knife sharpeners, fishermen, egg sellers, tripe and intestines sellers, sellers of wild greens, honey, even seasonal arbutus fruit.

Yet Pangrati had a large and rich market of its own, mainly food products for the gourmets of those days, Asia Minor refugees of the area and neighbouring municipalities. “Pangratikon” on the square was a typical grocery store; butchers, fishmongers, greengrocers, coffee-grinder shops, pastry-shops, containing the finest, mainly unknown in non-refugee neighborhoods, products. A favorite with children was Mr Erotas’ dairy and ice-cream parlor on the corner of Eftychidou and Ymittou . We began counting the ice-creams consumed in June and finished in September.

Ice for our iceboxes, kindling, wood and coal for heating as well as cooking were essential goods, supplied by Delaporta’s large coal house, high up on Ifikratous Street, as well as the huge icestockist on the corner of Aryvou and Filolaou and its small subsidiary on Ifikratous sreet. When kyr-Mitsos holding his curved pincers and cloths for wrapping up ice disappeared behind the door we worried whether he would reappear alive from the icy darkness. At some point, a Housewives’ Heaven opened on Eftychidou Street: Koufodimos, carrying household appliances of every kind. That was where ice-chests, gas and coal cookers were replaced by electric fridges and cookers, copper and earthenware vessels and containers by aluminium and glass ones, paid for in instalments. Plastic made its first appearance in the neighborhood in the form of little bags for the equally novel popcorn machine installed by Mr Potagas, always an innovator, in the entrance of his cinema. These little bags immediately became collectors’ items, and, correspondingly, rolled paper cones with toasted chickpeas and sunflower seeds became objects of contempt.

Marathon runner Chassomeris was our itinerant newspaper vendor, and the owner with his siblings of a news agents shop on the corner of Ymittou and Chremonidou. On the same street was Dimopoulos’ stationery and bookshop with the unforgettable odor of our school things.

Apart from the public schools there were – as far as I can remember- two private ones: A. Kalpaka’s “Kydoniai” on Timotheou Street, run by two sisters from Asia Minor, Athinoula and Alexandra Kalpaka, and the very Christian Vyzantion on Ymittou, its walls heavily scarred by civil war mortars. The Kalpaka sisters were socially and politically progressive. After the civil war ended I attended the early years of primary education there and have memories of Vassilis Rotas, the left wing writer who would show us puppet theatre Barba Mitousis stories, assisted by a lady called kyria Voula – evidently his partner, Voula Damianakou- but what could we know about such matters back then. Later on, I was to find out and understand many more things…

Photo 4: The Kalpaka Schools building today houses the 10th Vocational High School of Athens

Elvis Presley and Anna from Petralona. Topoi and my topi [6]

I was born in Athens, on Ifikratous street in Pangrati, beside the Pallas cinema that still exists today. This was an area with streets named after difficultly pronounceable ancient names which I would later encounter and with pleasure recognize in schoolbooks; a petit-bourgeois neighborhood we would nowadays call multicultural, surrounded by purely refugee [7] and strongly left-wing districts/neighborhoods, kept alive in my memory by the tiny houses of long-departed relatives and familiar street names, as part of the mythical geography of family narratives. In my childhood’s itinerary trying to orientate myself, I was moving within a genuine crossword, turning again and again in corners such as those of Filolaos and Bursa, Sappho and Trebizond.

The demarcating lines of the civil war were still fresh and vivid, not only in memory as imprinted and obvious on the wary behavior and reserved expression of people and the mortar-scarred facades of their homes. The old dividing lines between refugees and “locals” had faded, replaced and partly concealed by other, more hatefull differences and controversies.

Yet I was a child of “refugee origin”, which was not really clear to me; I had, however, realized that on one hand with certain families we were connected by some mysterious, strong bonds, – that remained rather inexplicable to me, since I knew that my selective and standoffish mother did not really appreciate them. Whilst on the other hand, referring to some other families, despite our perfect conditions of vicinity and social relationships, she would never lose an opportunity to express a kind of quasi- fatalistic understanding that also conveyed disapproval: “Oh well, what could one expect from people who are paliohelladites [8]?” (It took me many years to realize that the word was not an insult [9] ).

One of my early observations was that our family narratives contained many places, -many topoi – and many persons. Relations to both remained quite vague; hence extremely enchanting. Pretty later, I understood that just as the socially miserables are fascinatingly photogenic, the historically deprived and geographically much-wanderers are gifted story-tellers. Still, among the many topoi, there was one missing. The topos of a specific reference, which as a child I needed to clarify but I could not.

Winters were spent in Athens at school, and summer holidays in a village of Macedonia, with farmers close relatives. But even the cliché of a ‘homecoming’ would not work. Something remained unanswered – and how could it not, given the absence of a question.

I grew up in an environment that imposed defining and annoying terms and limits. Among separated -despite their apparently sincere attempts to communicate- constantly encreasing families of settlers who had been uprooted in various ways from various places of Greece. I remember women exchanging covered dishes with some local special food, cooked by them, revealing their origin. At the doorstep there would be warm and sonorous expressions of thanks; in the kitchen, according to my memories, disparaging remarks uttered about all these “cuisines”, deemed inferior to “ours”. I was feeling very distressed when it was our turn to reciprocate and sent in return the dish with its covered contents -I was usually the one to do this- imagining the equivalent scene playing out in the other kitchen. Something that never even crossed my mother’s mind, despite my timid and uncertain -since I could never really distance myself from her values- suggestions.

Among the topoi where I was growing up, the venues/ premises of the Refugee’s Association were playing an important role, nearly on a daily basis. My parents were regular members and I, since the age of 4 or 5, was compulsively taught to dance and to sing unintelligible songs in a coded -as I thought to be- language, which on the one hand caused me a strange excitement, an hedonic attraction, and on the other, a strong revulsion. I was feeling that like a shared secret that would assign /classify me in a particular big group, the group related to my parents’ people. Something I completely disliked /detested -maybe because it was obligatory- and I also detested the other children members of this group. Besides, this also kept me away from my friends and class mates: at school we would never be taught these dances and these songs, let alone this language.

In the neighborhood things were more egalitarian -everybody had something to be proud or ashamed of – depending on the way of seeing. The news dealer was a Cretan, the shoemaker a Pontian, the nurse was humpback, the grocer was gay, the baker came from Epirus.

The bakery was a central and revealing place for my undefined quests, as was the church: probably because both attracted large numbers of old women. Οld women revealed all that the “athenian” image of families was trying to conceal. They openly talked in their local dialects and their “foreign” languages -some even insisted on wearing village costumes -and gathered together accordingly. I had the impression that they arranged their meetings because, every noon, coming back from school, I would see two permanent groups outside the bakery, one conversing in Turkish, the other in Arvanitika [10]. The bakers’ wife would prepare traditional delicacies for each group’s customs, copying ideas from the trays taken there by housewives for baking: bagels, breadrolls, pies, brioche, tsourekia, lazarakia, fanouropittes [11] . She would even make kollyva, the sweetened, mixture of boiled wheat, pomegranate seeds, almonds and parsley, prepared for the dead and distributed to mourners at memorial occasions. This was a genuine ethno-local catering, the first I knew /I had ever encountered.

The Peloponnesian seamstress trained by an old Asia Minor woman, would make the costumes for the Refugee Assocition’s childrens’ dance group. My mother -for an unknown reason- ordered a boy’s costume for me. The room I would go to try it on was suffused by the wonderful smells of iron vapour, little tracing soaps and fabrics. I was ready to burst into tears and would have done so, if the seamstress had not prevented it, starting to cry before me. She had heard again another nasty comment about her husband, a collaborator and informer of the police during the German occupation, as everybody said. She was constantly in tears, having two brothers political detainees deported at the island of Makronisos [12] , and was never identified with her husband.

Her deep unhappiness drove her to folklore couture. She observed schools, photographers’ studios that rented costumes, homesick immigrants and set her imagination free. She copied from photographs, postcards, authentic pieces dug up from old chests and fabricated incredible outfits, selling or renting them out for national celebrations, parades, gymnastic shows, etc. That made her happy and instead of crying while she sewed, she would sing.

Despite my mothers’ strictures, I loved going there, picking up pins off the floor with a huge magnet, or doing whatever else she asked me to, as long as I could listen to her wonderful voice singing popular and folk songs that I was familiar with from the radio and liked them a lot. Both these activities of hers seemed to me promising opportunities for when I “grew up”.

So, being her favorite little one, I ended up with a rich collection of costumes:

the boy’s costume from the “homeland” dance group I detested most, and in any case could not wear anywhere else;

a beautiful ancient greek white tunic for the school feasts, ribboned with diagonal strips bearing the names North Epirus, Cyprus, Crete or Greece that we would interchange according to the event celebrated;

another that vaguely resembled a karagouna’s bridal costume for the gymnastic show at the closing of the schoolyear, where, as I was a tall girl in the primary school, I was tearfully leading the dance singing the song of the murderous Menousis, who killed his beautiful wife motivated by jealousy;

and -my very best- a costume of queen Amalia, with a short jacket and a real buckle for the Carnival.

Considering themselves threatened by the slandered Peloponnesian seamstress, the women of my family retaliated; next Carnival season, the silken bridal costume of an unexpected great-grandmother was produced, and I was recalled to patriotic order.

Thus ended my first contact with those educational entertainments. I respected my mood and thereafter refused to sing, wear costumes and dance. My mind retained the memory of an unexplained, uninterpreted dilemma, and my body that of an insufferable coercion toward something I could not deliver/ respond to.

I surrendered to aphonia and immobility. Until I discovered Rock and Roll. I would dance and it was as if my body had found its true limits. I was solely myself and that was all I wanted. Elvis set me free from bloodthirsty Menousis and. his friends

I acted the wild tomboy, playing ball at nearby athletic fields -later on I was to realize the weight carried by their names: Near East, National, Panhellenic. I was the life of impromptu parties, played hookey from school and loved distancing myself from the neighborhood and getting to know new people. I considered I was like all other children and this gave me confidence. I did not want to share family secrets or to understand, I did not want to know.

I kept one secret, however, even from those whose approval I craved/cared: reading. During the daytime I was wandering around, assuming a carefree attitude; at night, when I was supposed to be asleep in order to perform well at school next morning, I read in secret, in the light of candles, torches or candles. Luckily, I was living in a house with a lot of strange books that had travelled from afar, as had their owners. I was entranced by the ones that told of “distant lands and unknown civilisations” or of unusual, strange situations. I had discovered a way of escaping to a macrocosm and loved it. The topia, the balls and the games were getting almost useless. I was growing up…

I was to realize that, the day of my first encounter with death; that of a child like me, a classmate. An unforeseen experience that through absence cruelly conveyed the idea of topos and that of non-existence. That morning the bad news froze my blood and angrily threw away the ball I was holding. It was a gesture of farewell also to my childhood, which came to an end, as I melodramatically sensed it.

The ball was caught by Anna, who did not understand and brought it back. Anna was the first gypsy girl in my life. She lived in Petralona [13], and her family must have been among the first ones to attempt ‘establishing’ themselves in the city. She was 13, as was I. Nevertheless, we were not the same age. Totally conscious of her exclusion from my world, she consoled me by taking me to her neighborhood.

Strict rules concealed under apparent liberality are even harsher. For Anna, who was already defying them by denying to grow up and marry, this initiative was tantamount to a provocation. Thus, I learnt what gadjo [14] meant and Anna became even more obstinate. I don’t even remember how or why it was so difficult to meet up. It was like living a clandestine love affair -and it probably was- just what our passionate teens demanded. And, despite the gulf separating us we became real friends.

Anna had the gift of her culture for untruths, fabricating beautiful fantastic tales. I introduced her to the world of books and in return, she introduced me to that of untruths and travels. Anna had no topos; she created them through her tales. Or rather, Anna divided between many topoi, made her personal one up through her many tales and invited me to share it with her. In her cosmotopos, all that wounded was set right: she was neither poor, nor illiterate, nor stigmatized. I joined in her game. Not for a moment did it cross our minds to not believe each other in our stories /creations, be they the most outrageous.

We, adolescents, corrected and remade the world. I learnt that the world is the stories we tell of it and of us in it and made my peace -much later- with an epoch that upset me. When I realized that what upset me was that everyone around me was telling -or I thought I heard them do so- a different story about the same world; and I was baffled and angry, as small children are, when you change even the slightest word in their bedside tale.

Anna taught me to love untruths, to love listening to stories, to love travelling to places in search of stories, to find places through stories and to make my own stories. It came at a cost, as it still does. But I now know, having become an errant of utopia, that all senses of the words err, errant, errancy or errantry, [πλανώμαι, πλανιέμαι, πλάνητας, παραπλανώμαι, περιπλανιέμαι in greek], are, actually, one….

Anna taught me much of what anthropology would teach me later: for instance that I am always part of what I study, and that if I want to learn, I am not allowed to be an outsider, I cannot maintain an external, objective view; it is all about the possibility of participation, that is, reconstructing the world. That for every small place in this world, my body and my word will offer the greatest possibility for knowledge. Saying in other words what the poet wrote: I am your place. I may be no one, but can be all you want.

[1] It is, or rather was, the oldest cinema in Athens, first opened in 1925 and rebuilt in 1935 in art deco style by the architect of the interwar period Vassilis Kassandras (who also designed the Rex Theater bilding in Panepistimiou Str. and the building of the Army Pension Fund). In 1997 the open cinema on the roof of Palas has been classified as preserved as to its use, but unfortunately not the whole building so that it could be saved. After the death of Matthaios Potagas, the last cinema-lover among the members of the family of founders, the building was sold to a multinational corporation and will change its use. The State again failed to do anything.

[2] Initially, the area was called “Refugee Settlement of Pangrati”, in 1924 it was renamed “Settlement of Vyronas” until 1934 when it became an independent municipality. It took the name of the English poet and philhellen in 1924, on the centenary of his death in Messolonghi (1824). The “pro-refugee activity of the poet”, was the reason for this specific renaming, as is stated on the commemorative plaque placed next to Byron’s statue in April 1923.

[3] On November 16th 1953, the then Minister of Public Works Konstatinos Karamanlis had the tram lnes in Hafteia area torn up, which led the eradication of the lines to Kypseli, Pangrati and Ambelokipoi. The line 2, Kypseli-Pangrati was limited to Akadimia-Pangrati and replaced by the trolleybus 12, Koliatsou -Pangrati in August 1954. The end of the old tram came in 15th October 1960, when it was definitively discontinued. Many lines were replaced by trolleybuses and the tracks were removed or covered over by asphalt (Wikipedia, Athens Trams 1882-1977)

[4] Regarding this particular settlement see the article by Nikos Magouliotis «Ο οικισμός Ιλισού: Κρυμμένα ποτάμια και “γαλατικά χωριά” αυθαιρέτων στη μεταπολεμική Αθήνα» [“The settlement of Ilisos: Hidden rivers and “Gallic villages” of arbitrary buildings in post-war Athens” in Inside Story 11.1.2017 https://insidestory.gr/article/oikismos-ilissou as well as the earlier study «Ο Αυτόνομος Συνοικισμός του Ιλισσού στην Αθήνα» [“The Autonomous Settlement of Ilissos in Athens”] by Dimitris Filippidis, published in the volume “Shelter in Greece” edited by Orestis Doumanis and Paul Oliver, Athens 1979], with many photos and drawings

[5] Literally “Life-giving Font”, the term became an epithet of the Virgin Mary and she was often represented as such in iconography.

[6] Topoi and topi, similar sounding words meaning places –the first– and a kind of ball for little kids –the second.

[7] Cristian refugees from Asia Minors’ west cost, Pontus and Cappadocia who have been settled there after the forced population exchange with Τurkey in 1923.

[8] Paliohelladites: natives of the first areas to form the Independent Greek state “Hellas”. Α noun referring to the Greeks of Peloponnese and Central Greece, a term getting meaning only in relation to the inhabitants of the gradually later integrated into the state northern regions, called New Countries and mainly to the “refugees” from Asia Minor and Bulgaria.

[9] As in paliopaido, meaning bad child, since the first component in both compound words is the same “palio”, meaning both old and bad.

[10] Arvanitika: The dialect of the first Albanian-speaking immigrants who settled in Greece mainly between the 14th and 16th centuries.

[11] Tsourekia: a type of sweet bread resembling brioche; lazarakia: small human figures, baked and distributed to the children on st Lazarus’ day; fanouropitta: a type of cake made by people questing for something on St Fanourios day.

[12] Uninhabited islet, only 2.5nm away from the southeastern cost of Attica. From 1912 to 1952, Makronisos operated first as a concentration camp, then as a quarantine for the refugees and finally as an exile islet for Greek political prisoners. In 1989 it was characterized as a civil war historic place.

[13] Petralona was by that time a lower class neighborhood

[14] In romani langage means the person who is not gypsy.

[15] Main picture retrieved from flix.gr https://flix.gr/news/palas-pagrati-rumors.html

Entry citation

Terzopoulou, M. (2024) Pangrati in the 50s, Elvis Presley and Anna from Petralona. Topoi and my topi, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/pangrati-in-the-50s/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.121

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9