2015 | Dec

In an earlier publication on Anafiotika, a settlement on the foothills of the Acropolis, I had argued that some non-textual means of representing space, such as certain maps and tour guides, express a power relationship aligned to that of texts, stigmatizing and marginalising that settlement (Καυταντζόγλου 2001, 139-146). Those representations “misinterpret” an area that is full of life, by removing the key component of the long presence of its inhabitants and the meanings these people assign to the place they live in. Therefore, these non-textual means can be viewed as products and instruments of the hegemonic “monument-centered” perception of this location, in the same way as texts. Indeed, a parallel approach reveals interesting analogies.

This text focuses on a different body of visual representations of the Anafiotika settlement. It approaches the appropriation and consumption of that settlement by its inhabitants through practices that support an insurgent understanding and perception of the landscape, which could be characterised -for lack of a better word- as “popular” or “vernacular” [1].

These are illustrations of the settlement and the landscape, whose “agency” reinforces the status of the settlement as a lived-in area. They serve as a repository of local experience and memory. I believe that the use of these images can be seen as a practice, parallel to narration, that was developed by the inhabitants of Anafiotika in order to defend the protection of the settlement and, of course, their right to live there.

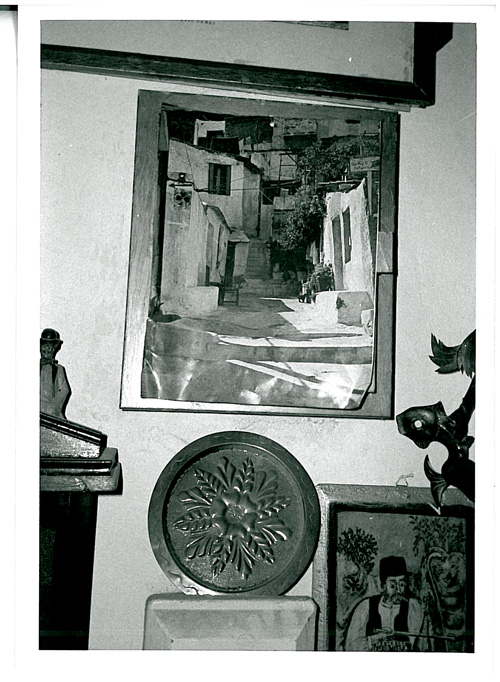

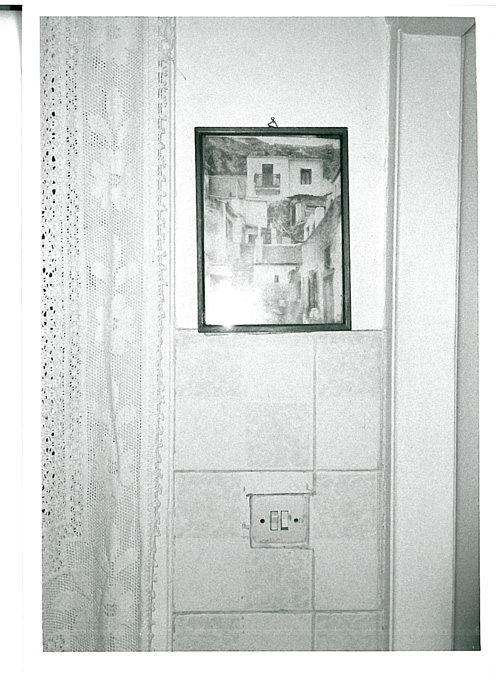

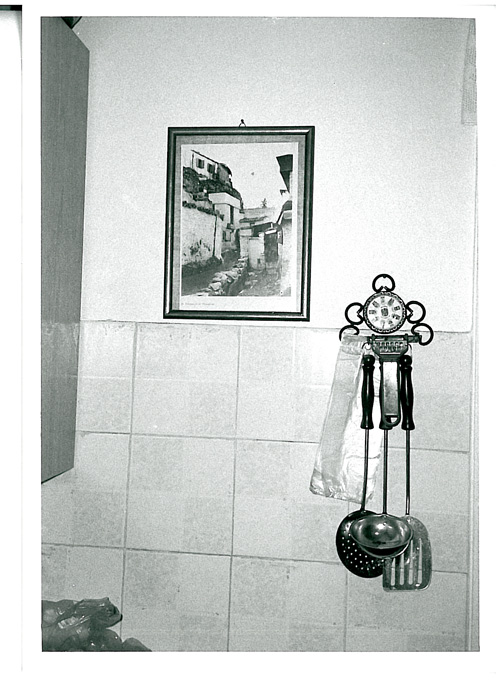

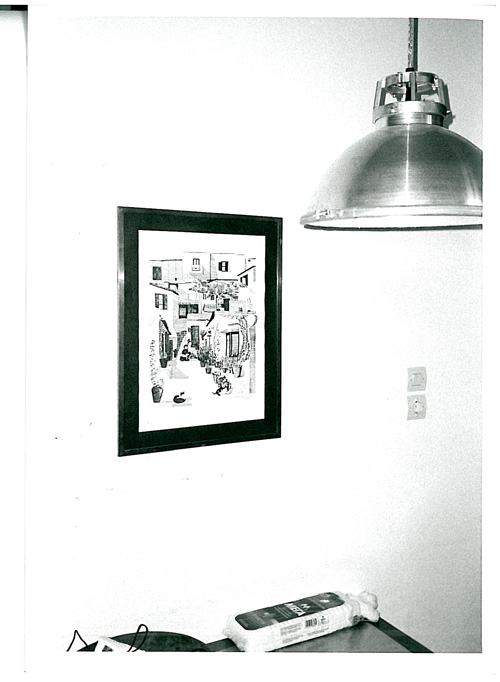

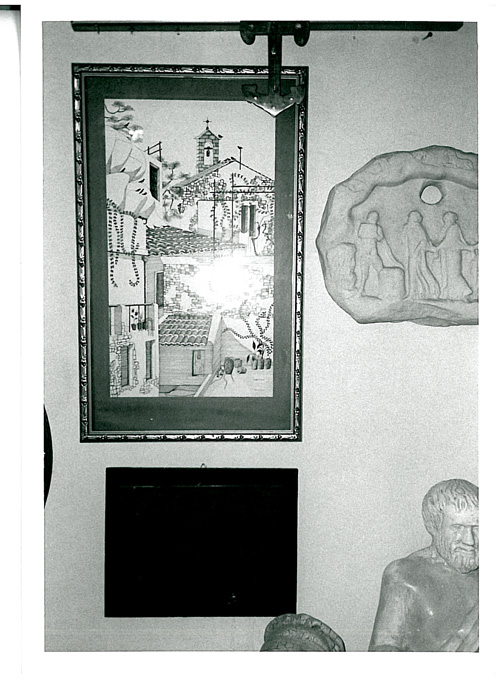

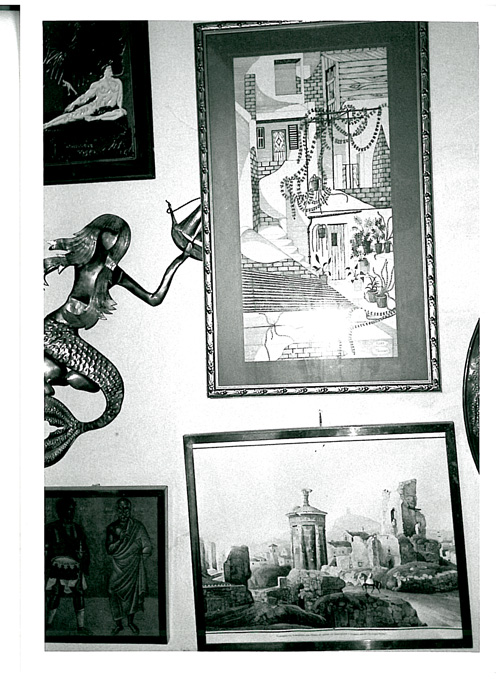

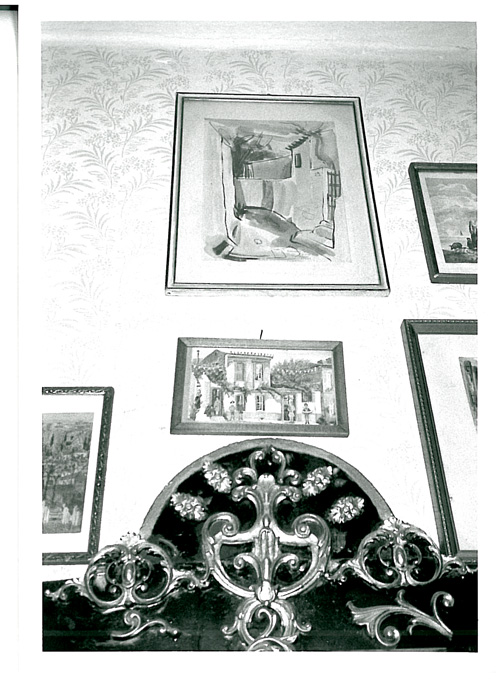

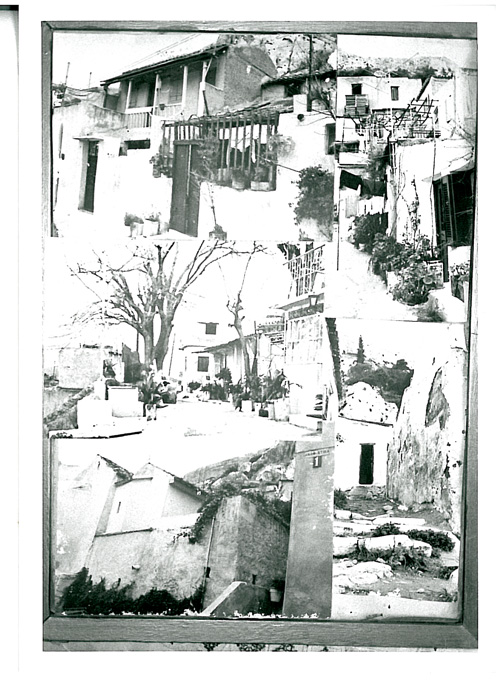

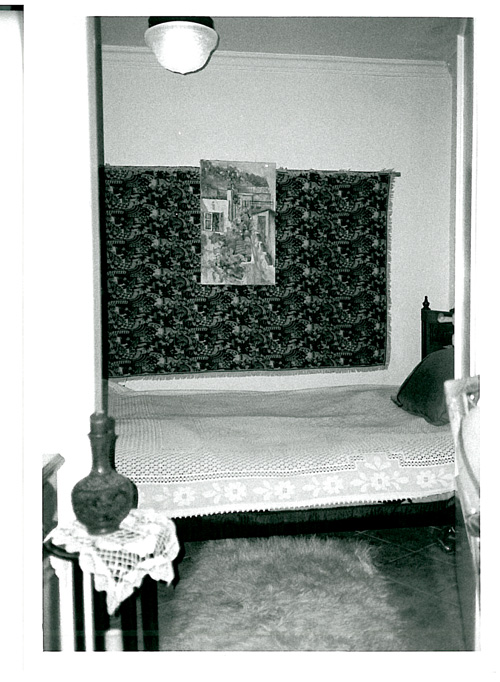

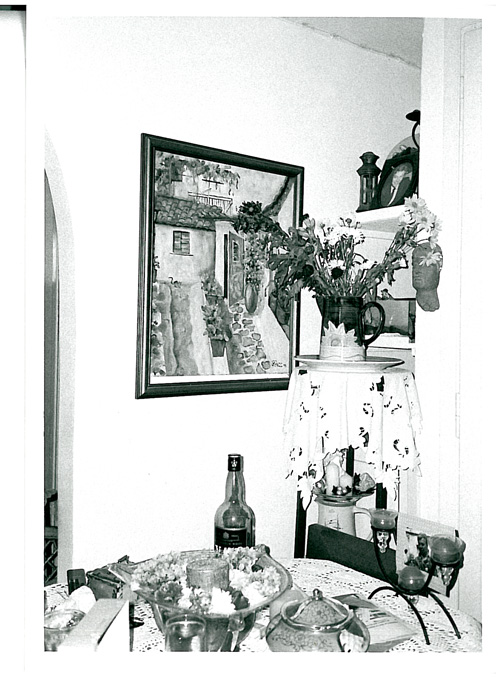

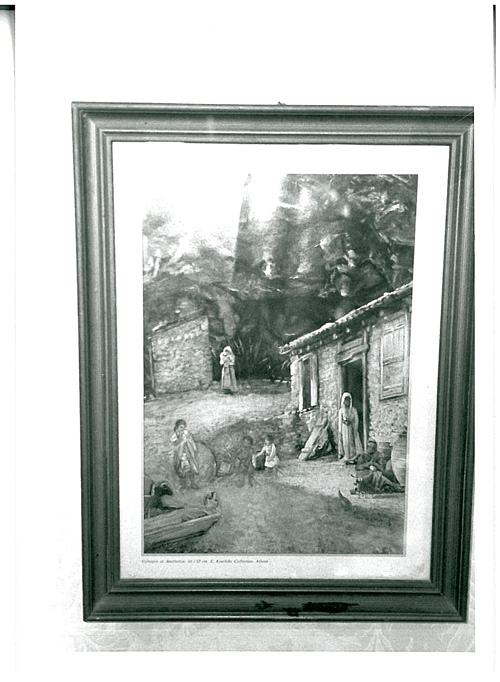

What does this body of visual material include? Virtual representations of various styles and materials: paintings, lithographs, photographs, etc. These are images and other “objects” that were purchased, inherited, donated, and placed inside the private, domestic space of residents. Therefore, they are part of what Miller (2001, 1) describes as “a cluster of objects in the space of the house, reflecting the actions (agency) of individuals and at times their weakness”… “of the material culture in the interior of the house, which appears as an appropriation of the surrounding world and a representation in our private space, creating and mediating social processes”. In this case, I argue that this visual material mediates the prolonged confrontational relationship between the authorities and the residents of the settlement. I propose a fundamentally different comprehension of the landscape and the place itself.

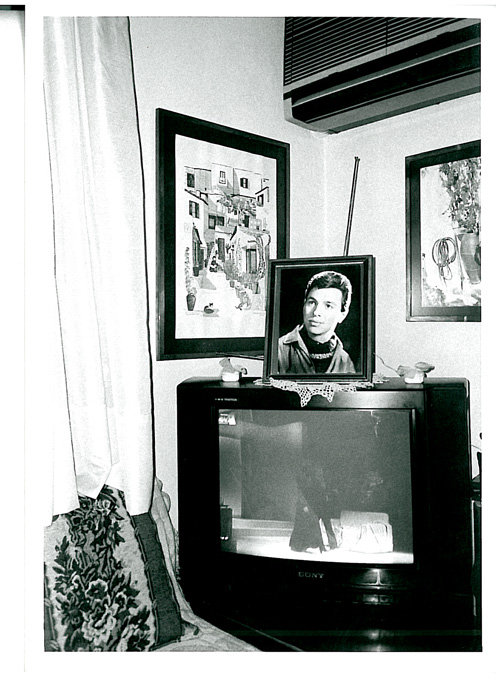

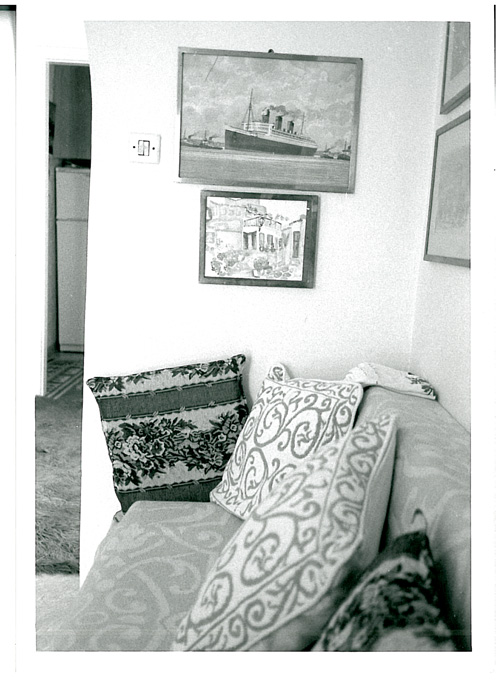

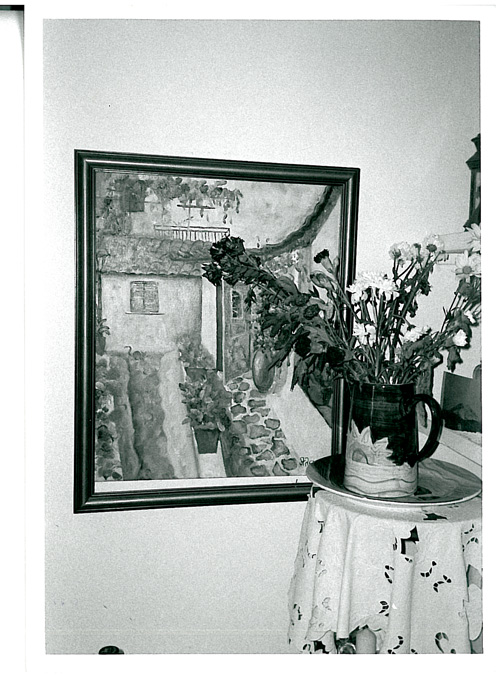

Visual material like paintings hanging on the walls, photographs placed on tables or on the television, have often become a conversation item and were shown to me as evidence [2]. The process of recounting how they were obtained and used (their consumption), reflects what Miller (1987, 189-193) describes as processing and re-framing the acquired object. Each item is thus transformed from an alienable object, with a monetary value, to an inalienable one, through its inextricable connection with the specific subject. The act of consumption radically alters the social nature of the object, although its material form remains unchanged.

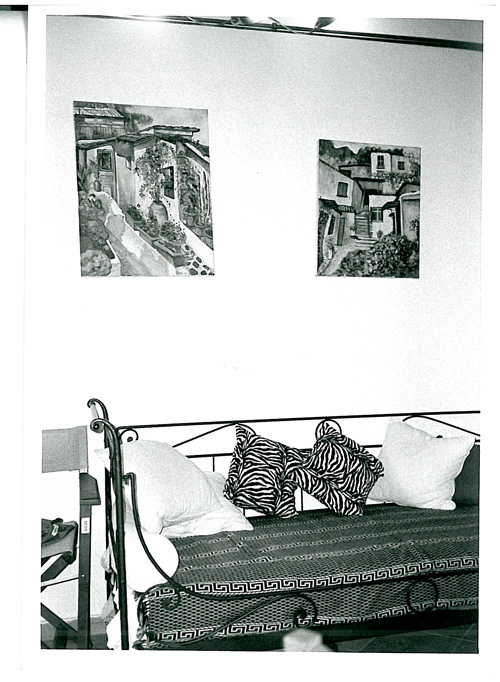

The narratives of how these objects were acquired by three inhabitants of Anafiotika, and their “trajectories” through space, are of particular importance. It is also noteworthy that some of that visual material is also present in homes of other residents. N’s house is decorated by two photographs of the settlement shot by the photographer Nelly, two acrylic paintings, an ink sketch and a small watercolour of the settlement. The story of the paintings by the painter (link) is enlightening: ‘N’ met him near his home while he was working on a painting of a view of the settlement. He ordered two paintings depicting the exterior of his house and the view from his window. When ‘G’, a neighbour of ‘N’, saw Alex’s paintings, he also ordered two more paintings depicting views of the settlement, which he placed in the living room of his house.

In E’s home, glassware, porcelain, statues and paintings of many kinds and styles, reproductions of 19th century works depicting houses of the settlement, photographs and other (more or less realistic) images thereof lie next to an original sketch, copies of which are held by ‘N’ and ‘G’.

Alex’s paintings would have very different meanings had they been exposed for sale in a souvenir shop or a frame shop elsewhere in the city, or if they had ended up in the hands of buyers without ties to the settlement. However, the fact that they were selected, acquired and placed in the homes of my interlocutors, transfers these works from an alienable to an inalienable condition (although these are copies and variations of a common theme). Moreover, I suggest that they have undergone one more transformation: as objects that were circulated and distributed in various houses of the settlement, they now form a common body of symbolic goods, which strengthen and reaffirm the collective defence of the place by its residents. Thus, while their acquisition is associated with the desire to decorate a private residential space, it can be argued that their presence turns that space into the ‘transmitter’ of a declaration related to outside space. It communicates feelings, experiences and connections to the place, while it recalls the history of the settlement and the difficult relationship with the monumental landscape. The agency of these works is further strengthened due to the fact that they are the creations of ‘outsiders’ who have understood and appreciated the historical value and the aesthetic of the settlement, as opposed to those who have devalued and marginalised it.

In the context of the tense relations between the settlers and the authorities managing the archaeological landscape, two sets of visual representations can be approached together with the textual and narrative strategies of the two opposing sides. By adopting an approach that examines different ways of representing the settlement, it is possible to outline the analogies between visual, text-based and narrative approaches: For example, on the one hand the irrevocable condemnation of the settlement as “shacks deforming the surrounding area of the Acropolis” by Dimitrios Vikelas (1897) or the condemnation of its residents as “foreigners” not belonging to historic Athens (Καμπούρογλου 1920, 1922) can be considered as analogous to maps, photographs and panoramas aiming at eliminating (excluding) Anafiotika. On the other hand, the colourful works depicting idealised flowering courtyards and the whitewashed houses of the settlement are the visual equivalent of scholarly texts that praised the charm of the humble settlement, like those of Karkavitsas (Καρκαβίτσας 1889) and Papadiamantis (Παπαδιαμάντης 1896). A tourist map depicting and naming the settlement but excluding it, through representation techniques, from the city’s history (Kaftanzoglou 2010) can be seen as the equivalent of ambiguous texts, like those of Biris (Μπίρης 1948, 1966 [1995]), which praise the aesthetic and historical value of Anafiotika, but do not accept the right of its residents to stay in that location.

A further analogy is the selective appropriation and representation, a vital technical element in both fields: the maps that promote monuments of classical antiquity,render ‘profane’ spatial elements invisible, while representations of the settlement focus on its picturesqueness, hiding aspects of its decline and decay. The textual rhetoric of the settlement’s opponents ignores its historical and architectural value, and insisting on classifying it as ‘out of place’. The rhetoric of the residents highlights the harmony in the community and the historical ties of that community with a place of particular beauty, which the residents have created and care for. This approach goes against the settlement’s stigmatisation as an ‘out of place’area, the strict surveillance of the residents’ daily lives and various interventions in their space.

The production and consumption of that visual material reflects the ideological and aesthetic choices of groups involved in the debate on the importance of the place. By exploring the contradictory virtual representations of this specific landscape in the context of lengthy negotiations regarding its importance, we can understand the multiple levels of the conflict between the ‘monumental’ and the ‘ordinary’, as well as multiple ways in which this conflict becomes visible.

[1] For a more detailed analysis, see Kaftanzoglou (2010).

[2] The use of the term “evidence” when discussing works with their owners echoes their desire to elevate said objects, assigning them a status of “strong” scientific evidence.

Entry citation

Caftanzoglou, R. (2015) Consuming images: Defending a place, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/anafiotika/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.49

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Καμπούρογλου Δ (1922) Αι παλαιαί Αθήναι. 1η έκδ. Αθήνα: Βασιλείου Γεώργιος.

- Καμπούρογλου Δ (1920) Το Ριζόκαστρον. 1η έκδ. Αθήνα: Εστία.

- Καρκαβίτσας Α (1889) Άγνωστοι Αθήναι. Τα Αναφιώτικα. 16η έκδ. Αθήνα: Εστία.

- Καυταντζόγλου Ρ (2001) Στη σκιά του Ιερού Βράχου. Τόπος και μνήμη στα Αναφιώτικα. Γκέφου – Μαδιανού Δ (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Ελληνικά Γράμματα, ΕΚΚΕ.

- Μπίρης Κ (1966) Aι Αθήναι από του 19ου εις τον 20ον αιώνα. Αθήνα: Έκδοσις του Καθιδρύματος Πολεοδομίας και Ιστορίας των Αθηνών.

- Μπίρης Κ (1948) Τα Αναφιώτικα. Φιλολογική Πρωτοχρονιά, Αθήνα.

- Παπαδιαμάντης Α (1954) Αι Αθήναι ως ανατολική πόλις. Στο: Βαλέτας Γ (επιμ.), Άπαντα, Αθήνα.

- Bikelas D (1897) Public Spirit in Modern Athens. The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine LIII(3): 378–392.

- Caftanzoglou R (2010) Producing and Consuming Pictures: Representations of a Landscape. In: Stroulia A and Buck Sutton S (eds), Archaeology in Situ. Sites, Archaeology and Communities in Greece, Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Plymouth-UK: Lexington Books, pp. 159–178.

- Miller D (1987) Material culture and mass consumption. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Miller D (2001) Behind Closed Doors. In: Miller D (ed.), Home Possessions: Material Culture Behind Closed Doors, Oxford, New York: Berg.