Large infrastructure projects

Kaparos George|Skayannis Pantoleon

Built Environment, Infrastructures, Planning, Transports

2015 | Dec

Construction-related infrastructure refers to technical (point or network) works or shells designed to support human economic and social activities (e.g. industry, education, transport). Large infrastructure projects are those requiring investments exceeding one billion dollars. The conditions which define the success of such projects have been of great interest internationally, because of the crucial effect these projects have on economic growth. The prevailing view is that their success is connected to whether they are completed within the tight boundaries of the “iron triangle” consisting of time, budget and initial specifications (Dimitriou 2014; Flyvbjerg, Bruzelius and Rothengatter 2003).

In this context, it is important to understand that investment in infrastructure, despite slow capital turnover rates, constitutes an investment outlet for capital, if profit is achieved. This is especially true when investments in the industrial sector, which ensures quicker recycling of invested capital and in consequence faster profit, are insufficiently profitable or secure (Harvey 1982).

Admittedly, due to their size (in terms of financial investment, scale, time commitment, etc.), infrastructure projects, and especially large ones, concern society as a whole and constitute one of its binding elements. Consequently, infrastructure policy is largely a state policy, reflecting conflicting trends and opinions (interests) with regard to the orientation and development of society per se.

Such an example is the case of large infrastructure works completed in the 1990s in Greece, which were realised due to two decisive factors: First, the planned overall development under the Community Support Framework. This incorporated the influence of or pressure from crises and opportunities in the construction sector (return of construction companies from the Middle East, efforts to expand activities in the Balkans etc.) as well as the goal to absorb funds and the emphasis on infrastructure provision which typifies the Greek regulation regime. The second factor was the influence of the upcoming Olympic Games at the time (Σκάγιαννης και Καπαρός 2013).

The most important of these major infrastructure projects were Attiki Odos, El. Venizelos airport and Attiko Metro in Athens, the Rion-Antirion bridge, the additions to Greek Motorway 1 and Egnatia Odos.

In all those cases the linkbetween infrastructure, city prospects and city planning has been very strong. In the case of Athens, the city’s connection to Attiki Odos, the new airport and Attiko Metro is obvious. The Rion bridge provides Patras with new prospects and development opportunities, especially when Ionia Odos is completed, while the connection of the city to Greek Motorway 1 is well under way, after a rather slow start. The same applies for the impact that Egnatia Odos will have on the cities within its scope as well as the restructuring it will cause to the surrounding area, bringing different urban system groups much closer with each other. One also needs to take into account the impact that the projects as a whole will have on the country’s economy, since they promote connectivity (completion factor) and will have multiple outcomes.

Ten (10) universities around the world coordinated by University College London (Omega Centre, Bartlett School of Planning), carried out a large-scale research concerning the success and importance of major projects (Dimitriou 2014),. The University of Thessaly (Department of Planning and Regional Development,) looked into Attiki Odos, the Athens Metro and the Rio-Antirrio Bridge. Here, we will discuss the first two as they are located in the metropolitan area of Athens.

Athens Metro (agreement for the main project)

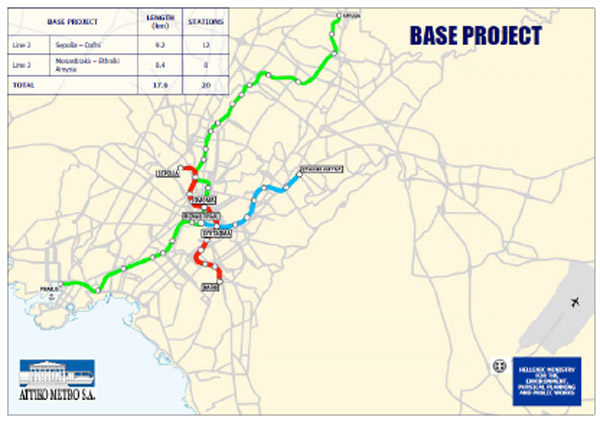

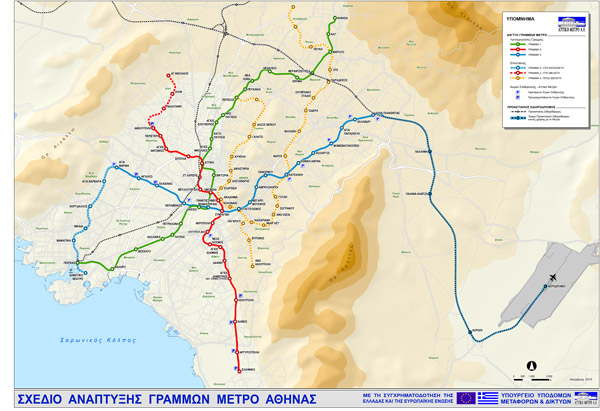

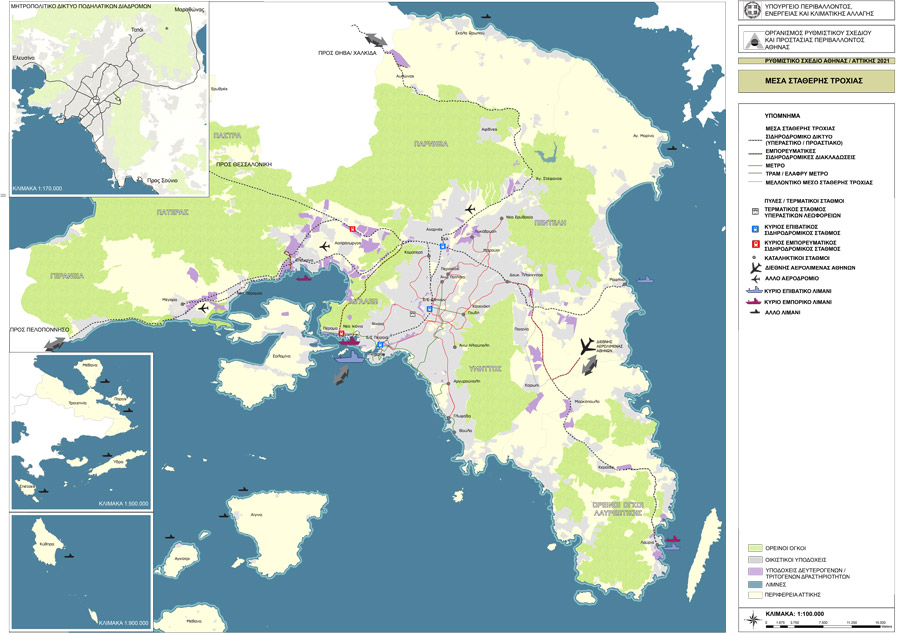

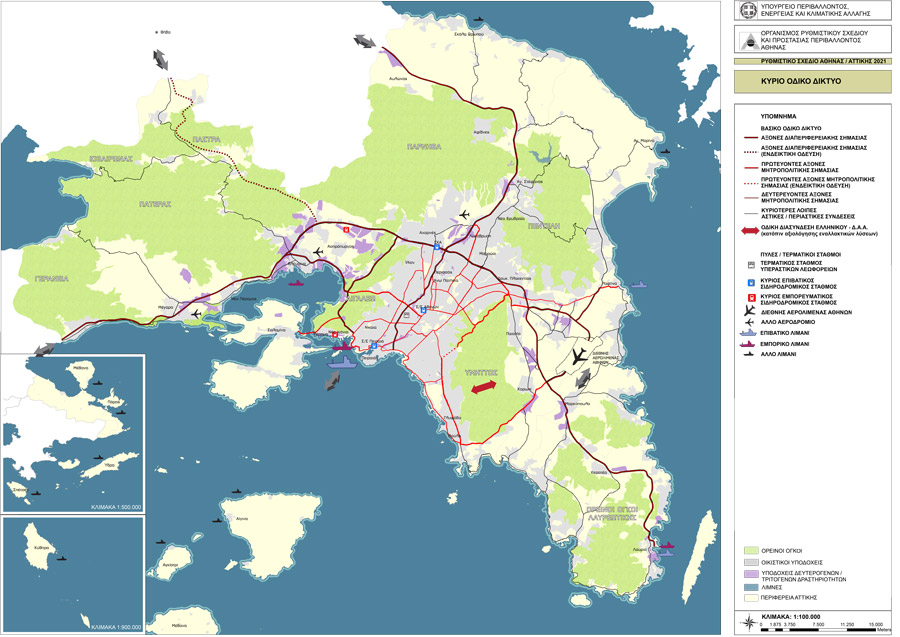

The main project of the Athens Metro comprises 20 stations, 17.6 km of track for lines 2 and 3, which cross through the city centre and are connected to the existing Line 1 (Figure 1). The project was publicly funded and is owned by the state owned company Attiko Metro SA, which is also responsible for its management. The concept for the main network of the Athens metro dates back to the 1950s (Νάθενας et. al. 2007). Subsequently a number of studies and plans were carried out during various times (Figure 2), while the project was included in the decisions for the central planning of Athens. In the mid-1980s, given the availability of funds due to European Community subsidies and loans from the European Investment Bank and following political pressure to resolve the swelling traffic problem, the Ministry for the Environment, Planning and Public Works included the project in its project plans for Athens (Σκάγιαννης και Καπαρός 2013; Kaparos, Skayannis and Pavleas 2010).

The tender for the project followed the Design & Build method for an overall lump sum and was completed in 1991, four years after the call for tender. Olympic Metro, a consortium headed by Siemens and Alstom companies (http://www.ametro.gr/) won the bid. The (basic) project was completed in 2003 at a cost of about € 2.7 billion (Attiko Metro SA, 2007), after a delay of approximately five years and with a cost overrun of one billion € (Kaparos, Skayannis and Pavleas, 2010). The delays were mainly due to redrawing tracks in order to protect archaeological heritage sites. Since the project’s completion the metro has more than tripled in length, while already in the beginning of 2015 more stations and extensions were designed and built.

According to the official announcements of the Ministry of the Environment, Planning and Public Works (http://www.minenv.gr/#), the main initial objectives of the project were to modernise and improve the public transport network of Athens and to reduce congestion, pollution and transit times. The project was also intended to serve as a catalyst for urban reconstruction and to increase employment opportunities. Additional and significant targets of the project, that were later included, were the interconnection between different public transport modes and the metro’s contribution to the development of multiple centres within the metropolitan area (Λαλιώτης, 2000).

Figure 1: Athens metro – main project

Source: www.ametro.gr

Figure 2: Athens Metro – current version (2015) and development plan

Source: Link

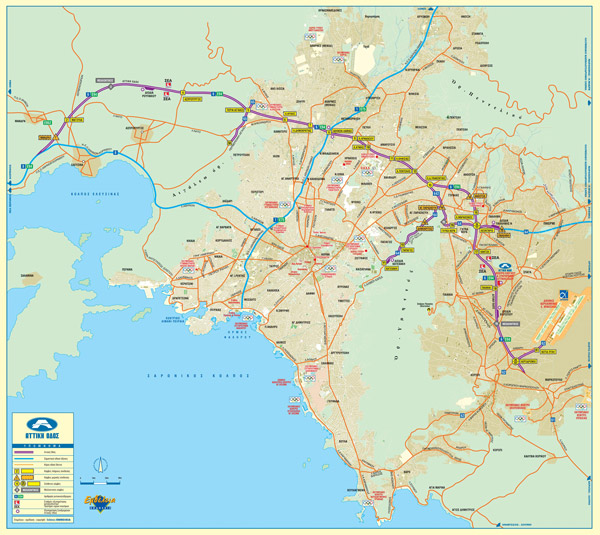

Attiki Odos

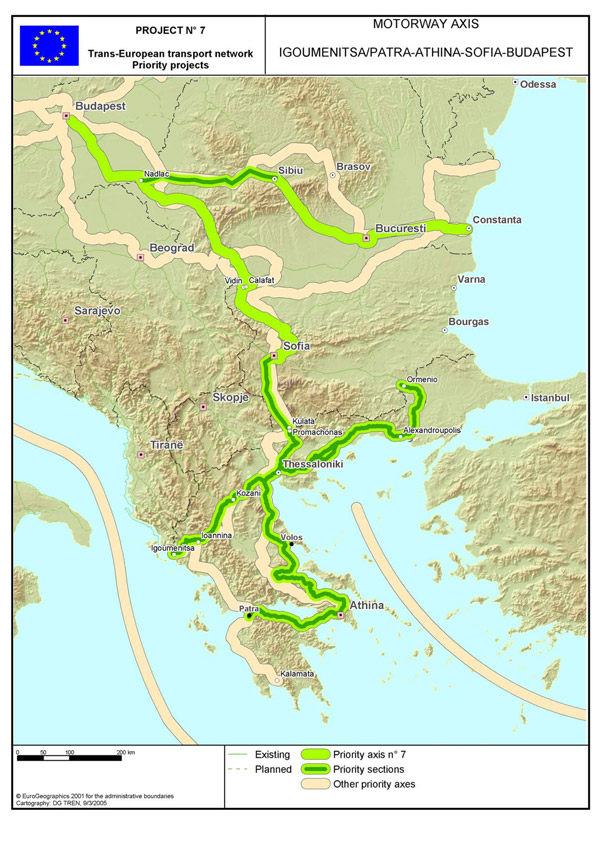

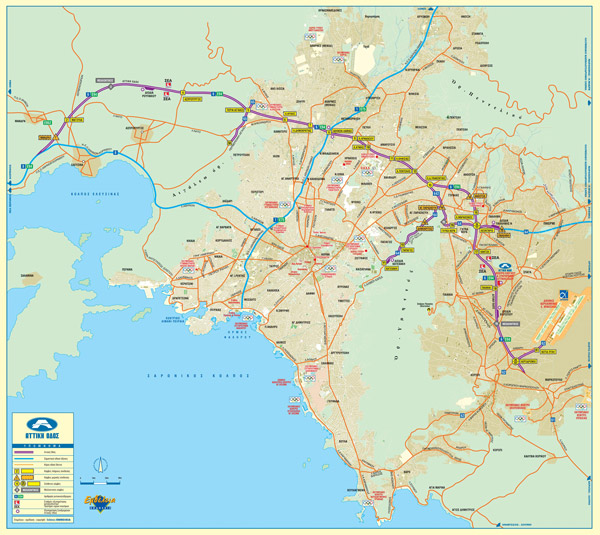

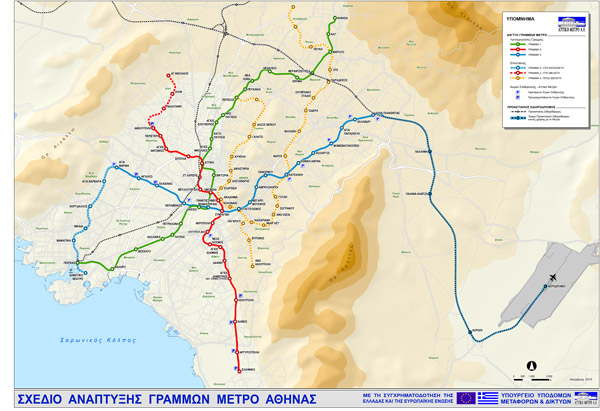

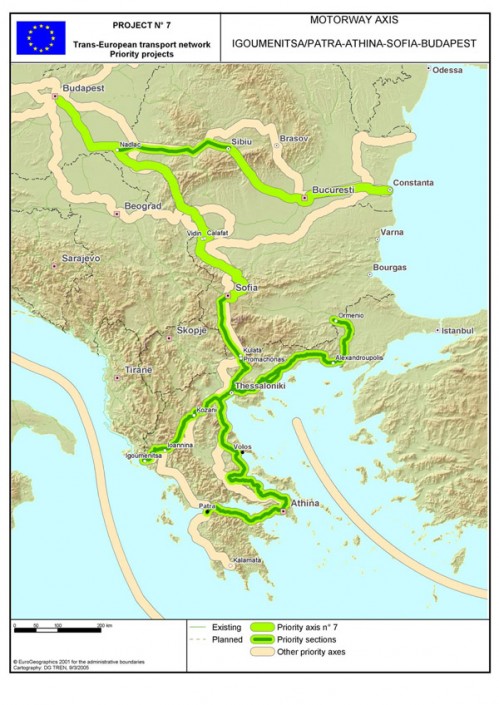

Attiki Odos (AO) is a tolled, closed motorway of 65 km length. It is the regional highway of the greater metropolitan area of Athens and the backbone of the road network of Attica. It connects 30 municipalities of the metropolitan area with the major road, air transport, port and railway infrastructure. AO connects the new airport (El. Venizelos) to the city of Athens and is also part of the PATHE axis and the priority axis 7 of the Trans European Networks – Transport: Patras-Athens-Thessaloniki-Sofia-Budapest (Figure 3). AO consists of two almost perpendicular motorways: a) The 52km long Elefsina-Stavros-Spata freeway and b) the 13 km long Ymittos Western Ring road motorway. It includes 9.4 miles of extensions on three highways which assure connection with AO (Figure 4) ( http://www.aodos.gr/summary.asp?catid=19571).

Figure 3: The Transeuropean Axis 7

Source: Link

Figure 4: Attiki Odos (2015)

Source: Link

The project was a Design – Build – Finance – Operate – Maintain concession agreement , between the Greek government and the concessionaire, ATTIKI ODOS SA. It was financed from public and private sources and the concession agreement will be terminated in 2023. The construction was carried out by ATTIKI ODOS JOINT VENTURE, while the operation and maintenance of Attiki Odos are managed by ATTIKES DIADROMES SA which is owned by EGIS ROAD OPERATION and ATTIKA DIODIA SA. The tolls are managed by ATTIKA DIODIA SA, whose shareholders are AKTOR CONCESSIONS SA, J & P AVAX SA, PIRAEUS BANK SA, ETETH SA (owned by J & P). ATTIKI ODOS’ shareholders are AKTOR CONCESSIONS, J & P AVAX SA, PIRAEUS BANK SA, ETETH SA (owned by J & P), EGIS PROJECTS SA (TRANSROUTE INTERNATIONAL) (Attica Diodia SA, 2014; http://www.aodos.gr/summary.asp?catid=19494 Attiki Odos SA, 2014).

The initial idea to build Attiki Odos dates back to the 1947 Doxiadis plan, which became more concrete with the Smith study of 1963.

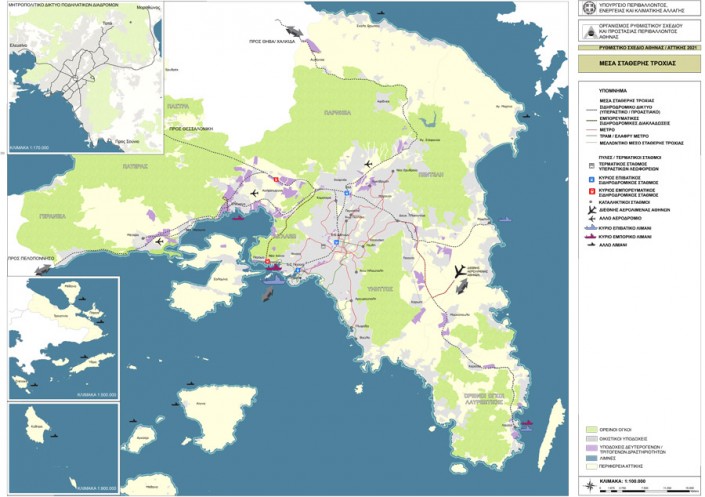

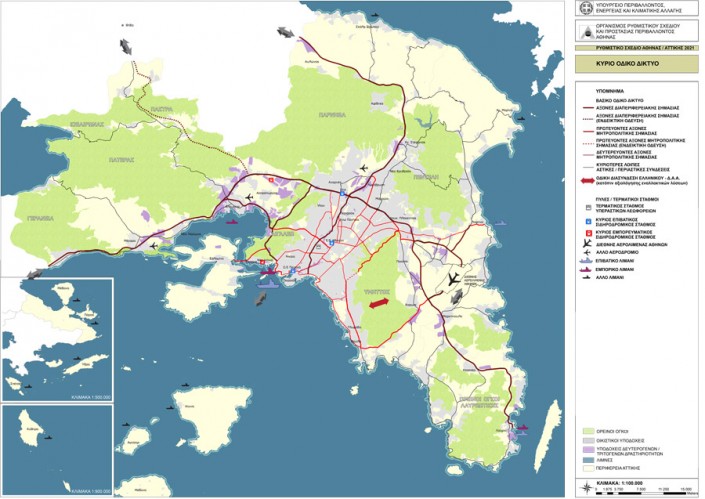

Later, a number of studies and plans (1972-1975, 1978-Athens Attica Regulatory Plan [PLA] 1985), were carried out at various points in time. Eventually, the project was incorporated inthe central planning for Athens, due to the pressure created by the city’s traffic problems and thanks to the new possibilities provided by European Community funds. A significant parameter was the decision to locate the new airport in Spata and the obligation to complete the road connection between the airport and PATHE prior to the operation of the new airport. These arrangements were permanently included in the PLA 2021 following the construction of Attiki Odos and of the new airport (Figures 5 and 6).

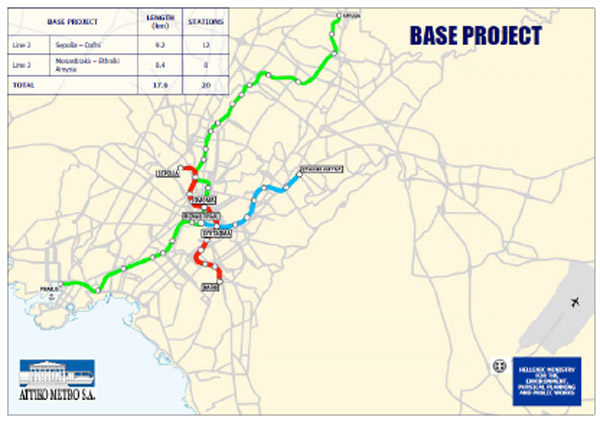

Figure 5: Master Plan Attica-Athens 2021 (N.4277 / 2014). Track-guided transportation

Source: Link

Figure 6: Master Plan Attica-Athens 2021 (N.4277 / 2014). Road Network

Source: Link

The tender for the project was started in 1992, it was held in two phases and finally in 1996 the concession agreement was ratified by the Greek Parliament (Law 2245/1996) which awarded the concession to Attiki Odos SA. Funding was secured with significant delay, in 2000.

Construction finished in 2003 and the main project cost rose to € 1.249 billion(http://www.ametro.gr/), while the overall budget increased to € 3.2 billion due to additional projects, higher than expected compensation for land expropriations, planning amendments, archaeological works, additional expenses for engineers, moving utility networks (Kaparos, Skayannis and Pavleas 2010). Most sections of the project were delivered before their planned deadlines, while the Ymmitos Western Ring road was delivered with six months delay(on 30/08/2003) and the Egaleo-Metamorfosi section was delivered ten months late (on 03/08/04).

According to the concession contract (1996), the main original objectives of the project were to address the transportation problems and the pollution that the radial network had created. This would reduce transportations through the city centre and would result in improved quality of life and a more balanced and sustainable development in Athens. Other additional targets set by the government in 2000 were the construction or upgrade of port facilities in eastern Attica (Rafina – Lavrio),flood protection projects in Attica and the strategic redesign of energy and communications networks in Attica (http: / /www.minenv.gr/#).

These two major projects in Athens show that the construction of large technical infrastructure in Greece is crucial for everyday life, for urban planning and for the future of metropolitan areas. A major issue with such large projects is that they are often designed retrospectively thus bypassing the city’s urban-spatial planning procedures. As a result, they don’t always fit “organically” into urban space. This is a key factor, among other reasons, such as the lack of sufficient and meaningful consultation and realistic projections, that these projects do not manage to deliver the benefits anticipated in their initial planning although they manage to solve significant functionality issues for the city. At the same time, they often create unforeseen consequences for the city’s organisation and operation, revitalise its planning and give momentum to other large projects / interventions. Therefore, the pace and the dynamics of urban planning is often incompatible with the pace and dynamics of planning for large projects.

Entry citation

Kaparos, G., Skayannis, P. (2015) Large infrastructure projects, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/large-infrastructure/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.38

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Λαλιώτης Κ (2000) Ομιλία στο Συνέδριο για την Μελέτη Ανάπτυξης του Μετρό. Αθήνα.

- Νάθενας Γ, Κουρμπέλης Α, Βλαστός Θ, κ.ά. (2007) Από τα παμφορεία στο μετρό – 170 χρόνια δημόσιες συγκοινωνίες Αθηνών-Πειραιώς-Περιχώρων. 1η έκδ. Αθήνα: Μίλητος.

- Σκάγιαννης Π και Καπαρός Γ (2013) Τα έργα υποδομών στην Ελλάδα και η παρουσία των μεγάλων έργων μεταφορικών υποδομών: μεταβαλλόμενα υποδείγματα και προτεραιότητες. Αειχώρος 18: 13–65.

- Attiko Metro SA (2007) Annual Internal Economic Report. Athens.

- Dimitriou HT, Low N, Sturup S, et al. (2014) What constitutes a ‘successful’ mega transport project?/Leadership, risk and storylines: The case of the Sydney Cross City Tunnel/The case of the LGV Méditerranée high speed railway line/Dealing with context and uncertainty in the development of the Athen. Planning Theory & Practice, Taylor & Francis 15(3): 389–430.

- European Commission (2005) Trans European Transport Network Priority Projects. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/ten/transport/maps/doc/axes/pp07.pdf.

- Flyvbjerg B, Bruzelius N and Rothengatter W (2003) Megaprojects and risk: An anatomy of ambition. Mc Leod C (ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harvey D (1982) The limits to capital. 1st ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Kaparos G, Skayannis P and Pavleas S (2010) Athens Metro Project Profile. Volos. Available from: http://www.omegacentre.bartlett.ucl.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/GREECE_ATHENSMETRO_PROFILE.pdf.

- Skayannis P and Kaparos G (2010) Athens Metro Base Project: HLR Report. Volos.