2015 | Dec

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times (…)

in short, the period was so far like the present period,

that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being

received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison onlyCharles Dickens , 1859

A Tale of Two Cities [1]

I am not sure whether I should pretend to know nothing about Omonia Square. I guess for starters that as a word – a common noun meaning concordance – omonia (in greek: ομόνοια) is definitely sandwiched among other words in the dictionary and, there, it finds its meaning again and again when spoken or written (Figure 1). Similarly, as a proper noun, a square’s name in particular, I know with certainty that it can be found in lists, city maps and signs on building corners, marking a special place (Photo 1) – a reminder (perhaps) of some ancient deity (Figure 1). By extension, Omonia Square in Athens and the Place de la Concorde in Paris, although two different places, share, in addition to the same name, the word ‘square’ which describes a location in the city (Figure 2). Omonia square seems therefore to oscillate between the composite interpretation of these two words, supporting a common collective identity and the everyday experience that inevitably escapes surpassing any semantic identification whatsoever. From this point of view, these two squares are homologous. They go separately back and forth from word to space and place and vice versa, as Certeau would say, and while they coincide lexically, at the same time they diverge as they incessantly mark on them different transformations of the city. Two public open spaces gathering people who consent or once consented to something with a consistent mind. Omonia Square; a proper noun speaking for itself.

Figure 1:

| concorde/ομόνοια· 1798, Γαλλία concorde, s. f. Union de coeurs et de volontés, bonne intelligence entre des personnes.

Μτφρ.: Ένωση των καρδιών και των επιθυμιών, κατανόηση μεταξύ των ατόμων. · 1835, Ελλάδα ομόνοια, η. (ομόνους) Ομοιότης, συμφωνία κατά τον νουν, τα φρονήματα […]έτι δε και ως Θεά τις […]

etymology Greek ομόνοια […] < επίθ. ομόνο(ος)/-νο(υς) […] Latin concorde adv. [cf. CONCORS] concors [CON- +COR]: a meaning influenced by false etym. from chorda […] Conjuring in feeling and opinion, agreeing, like-minded: (of a body of people) mutually agreeing […] Trans.: adv. [See CONCORS] concors [CON- +COR]: a meaning influenced by false etymology of the word καρδιά […] to consent in feeling and opinion, to have the same opinion: (for a group of people) to consent in agreement. Dictionaries

|

Figure 2:

| platz/place/πλατεία

1854, Germany platz, […] entlehnt aus dem gleichbedeutenden franz. Place […] das zurückgeht auf lat. platea (gr. πλατεῖα, nämlich ὁδός breiter weg) […] 2c) öffentlicher platz eines ortes zu zusammenkünften, märkten: gmeiner platz und ort, da man sich versamlet. Trans.: […] borrowed from the French word Place […] and the latin Platea (gr. πλατεῖα, wide road) […] 2c) a space open to public for gatherings: a common space and place, where one meets other people. 1798, France place, signifie aussi un lieu public découvert, et environné de bâtimens, soit pour l” embellissement d’une ville, soit pour la commodité du commerce […] Trans.: also means an open public space, surrounded by buildings either for the beautification of a city or for trade facilities […] 1835, Greece πλατεία, fem., street or avenue, wide road (a square) Dictionaries (see Fig.1) |

Photo 1a, 1b : Signs on building corners, Omonia square/ Athens and Place de la Concorde/ Paris (Source: F. Kafantaris)

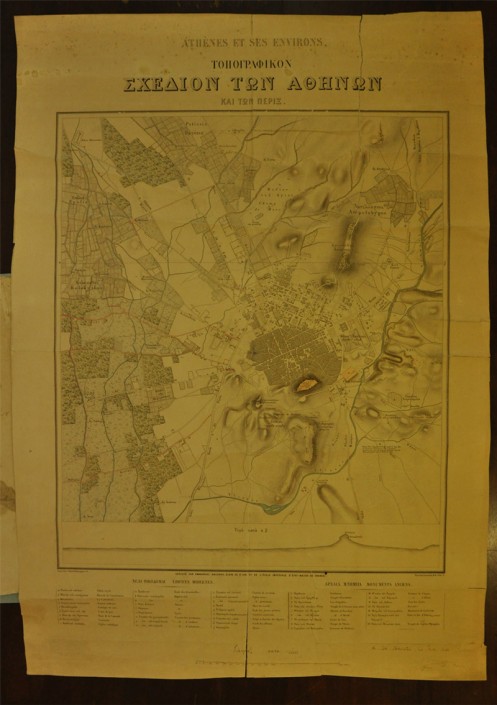

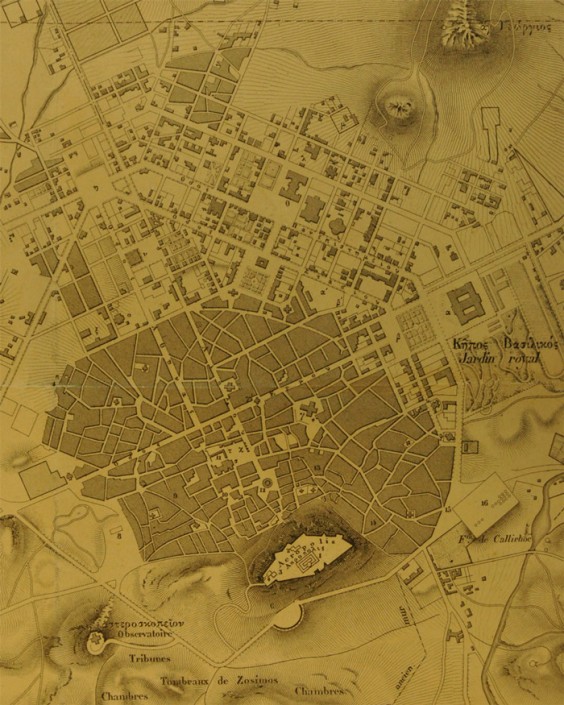

Omonia Square in Athens is located at the junction of Stadiou, Athinas, Pireos, Agiou Konstantinou, Tritis Septemvriou and Panepistimiou Streets and has borne this name for years. Marked as uninhabited and outside the old city walls in Fauvel’s plan circa 1780, marked as a field still in the topographical plan drawn up in 1832 (Kleanthis & Schaubert), this area, was abruptly found on the right angle of the triangle that geometrically formulated the city’s urban development and formed the backbone of the first plan prepared by the architects Kleanthis and Schaubert in 1833, after Athens became the capital of the newly established Greek state. The two architects placed the administrative centre of the state here, the ministries and the palace that meant to be the house of the young kings, Otto and Amalia. The plan was soon modified. The palace moved, first west and finally east, leaving behind a powerful semantic landscape as a basis for this location: to the south, views to the classical acropolis through the eyes of the recently arrived western culture and the strategic location of the now empty space as an end point of a straight line that would bring the port of Piraeus inland again.

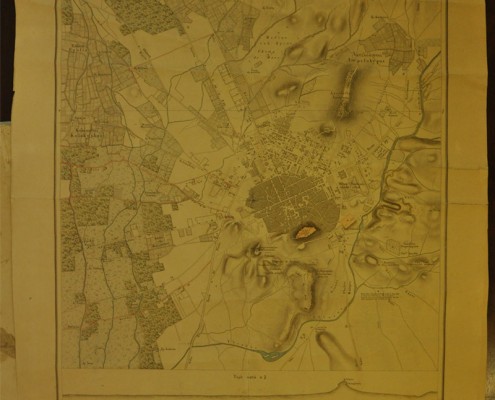

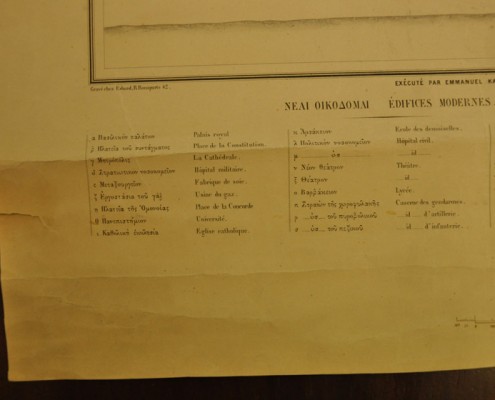

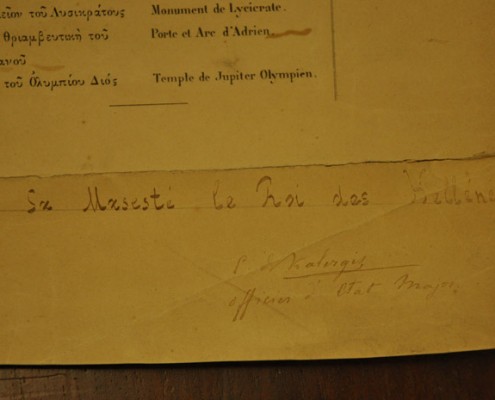

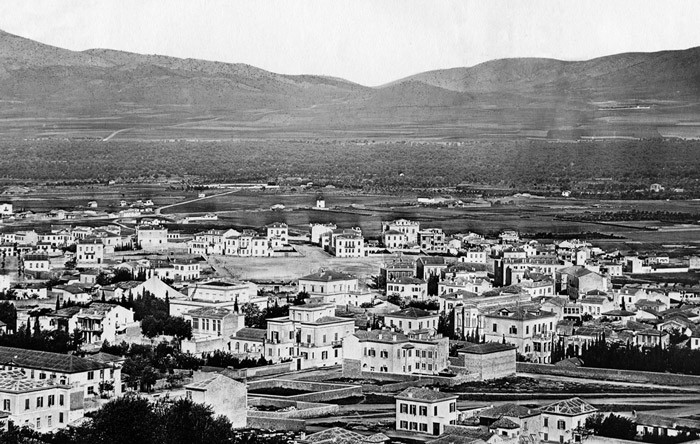

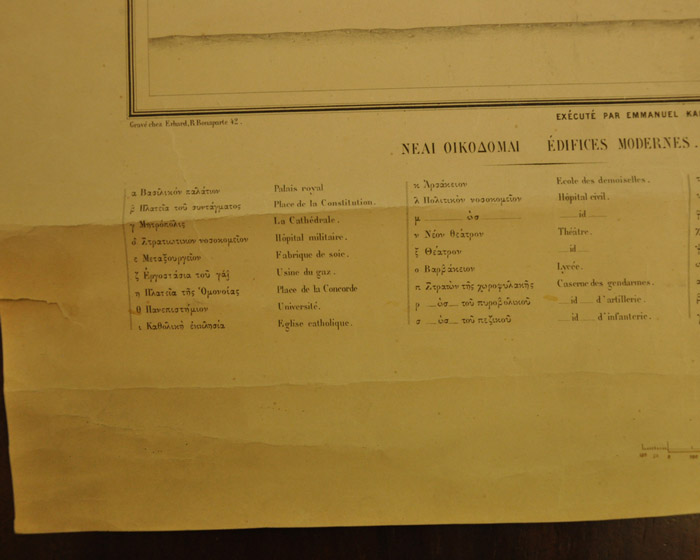

The first conceptual changes of the northern end mark the start of the corrective plan of the architect Klenze in 1834. In this plan, the square features the church of the Saviour which would fulfil the pre-revolution promise of the Nation to its people (Government Gazette 29.01.1834) and the layout changes from rectangular to circular. The temple was not erected, the geometry did not change and the square was renamed from Anaktoron (Palace) Square to Othonos Square (Otto Platz). The building regulations of the buildings to be built around it in the future were provided by decree in 1836 (Government Gazette 15.5.1836), taking into consideration for the first time the morphological evolution of the urban landscape there, and maybe the flow of people that would cross it everyday within the following years. In the topographical plans of Athens published from 1837 (Aldenhoven topographic plan) to 1852 (topographic plan of the French military cartographic mission) the area closest to the square is shown unbuilt and the square appears to have no activity given that Tritis Septemvriou Str. was opened much later. The layout of the square changes from circular to rectangular again following a decree in 1851 (Government Gazette 18/01/1851), while the buildings around the square are recorded for the first time in the 1860s, both in Emmanouil Kalergis’ plan (Photos 2a, b, c, d) and in the photographic panorama of Paul Baron des Granges (Photo 3), a sample of the building activity of the previous years. Furthermore, the most important information regarding our object of study is the fact that in Kalergis’ plan, the formerly named Otto square was recorded as ‘Omonia Square – Place de la Concorde’ and the square east of the palace in front of the ‘Kipos ton Muson’ as ‘Syntagma square’ [2].

Photos 2a, 2b, 2c, 2d: The plan of Emmanouil Kalergis (Source: National History Museum: Maps Archive)

Photo 3: Omonia Square around 1865 – Paul Baron des Granges (Source: Transformations of Athens)

More specifically, the word omonia begins to be associated to this particular location in 1862, emerging from decisive political movements that finally gave it – possibly as a foreign loan – the title Omonia. The deposition of King Otto on 10 October of that year led to its renaming, carrying the promise of the Constitutional Assembly to convert the form of government into a constitutional monarchy, authorised the National Assembly to appoint a new king and to adopt a new constitution [3]. Therefore, the double note in the Kalergis map is a gesture indicating a change of political regime in space by conceptually shifting two of the Triangle points of Athens into something new [4]. When the King was (almost) deposed, every “national store, place and ship bearing the name of the royal couple also ceased to exist” (Paligenesia 23.10.1862) and since Syntagma Square was already called that way since the early 1850s [5], now, together with Omonia square, the Otto University should be renamed to Greek University and the square on Pireos Street near Metaxourgio, from Loudovikou (Louis) Sq. to Eleftherias (Liberty) Sq. The new political situation and the new name of Othonos Square were publicly announced on 12 October, during the inaugural speech of the president of the interim government, Dimitrios Voulgaris and were celebrated with an open mass on the square.

| The newspaper The New Generation (I Nea Genia) (13.10.1862) noted:

“Yesterday, at four, the square bearing until now the name of the Bavarian deposed king was renamed to Omonia Square (…)” and the column ‘Government Acts’ of the Tilegrafos newspaper, issue of 19th October 1862 featured the relevant speech titled: “A speech to the people of the capital by the president of the interim government during the celebration of 12 October 1862 in OMONIA square” where it says, among other things: “Fellow citizens! The hopes and desires of this nation have been fulfilled; sovereignty has arrived (…) the old regime is forever gone, and a new one has succeeded it (…). I propose mutual love, mutual faith, concord, fraternity and generally the maintenance of order; for only with those are nations blissful. (…) let us take a vow on this square, that has now taken this beautiful name, Omonia, and say ‘I vow to be faithful to my country and obedient to the national decisions” |

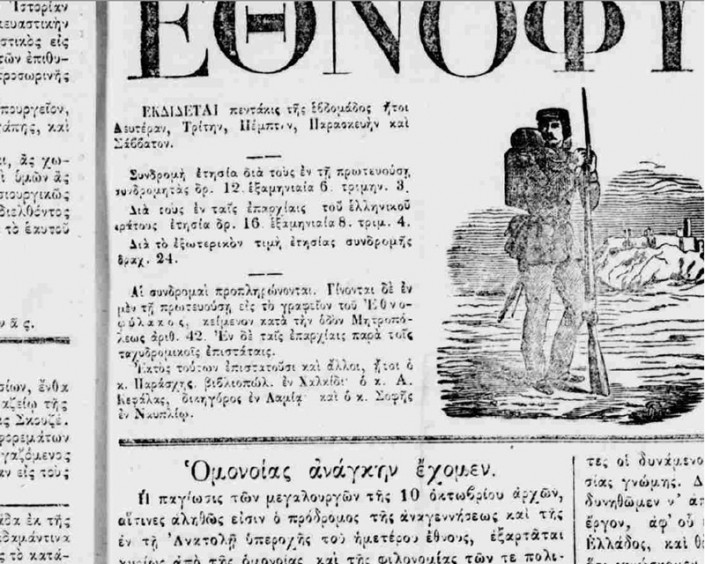

In the days following the King’s dethronement, Omonia appears in the articles of newspapers sometimes with a capital sometimes with a small first letter. The titles of three articles in consecutive issues of the newspaper Ethnofylax are a typical example thereof: ‘Invitation to omonia’ (16.10.1862), ‘The order and omonia’ (18.10.1962), ‘We need Omonia’ (20.10.1862) (Photo 4). In 1861, Athens had a population of 41.258 residents and 4.212 buildings (ETVA, 1991) a few of which surrounded Omonia (Photo 3). After that, the ‘post-revolutionary’ square witnessed, in the name of concord, the apex of (at least) two politically restless decades that would complete the revolution of September 1843, in expectation of the future; better or worse.

Photo 4: Issue of the newspaper Ethnofylax: ‘We need Omonia’ (20.10.1862)

And while October’s revolution successfully and bloodlessly removed the King’s name from the square, the renaming of Place Louis XV in Paris to Place de la Concorde , was achieved gradually and cost the royal couple something more than the throne. A few months after the fall of the king and the establishment of the French Republic in September 1792, the King was found ‘guilty of conspiracy against public freedom and of plotting against national security’ by the National Convention of the Montagnards and the Girondins that condemned him to death. Louis Capet and Marie Antoinette (and others) were decapitated in 1793 in the Revolution Square, that took its name by the second revolution, but not before his predecessor’s statue was replaced with guillotines [6]. The name Concorde was given for the first time to the square after the French Directory fell and Napoleon arrived together with the French Consulate in 1799, aspiring to leave the monarchy behind ‘for good’ and to pass a new Constitution [7]. In 1814 or in 1818, the square was renamed again to Place Louis XV, in 1826 to Place Louis XVI and finally to Place de la Concorde in 1830 [8] after the July Revolution that led to a liberal constitutional monarchy and the fall of King Charles X.

Photo 5: Execution of Louis XVI in the Place de la Révolution (Source: Bibliotheque Nationale de France)

Accordingly, Athens’ Omonia square, was at the centre of semantic tensions, either hypothetical or actual, although the name did not change and remained stable since 1862. The statue of the king, which a 1859 resolution proposed to be erected in the square, would probably have been destroyed by the revolutionaries but was never actually erected (AION 17/10/1862).This did not prevent King George I from having Ziller design there, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the 1821 revolution, a quadrangular column that would bear the landing of Otto in Greece (Paligenesia, 26.3.1870) on one side. Nor did it prevent Hoffmann in 1908, within a wider urban planning recommendation, to propose the building of an obelisk with the statue of King George in its base in Omonia (at the time, Luxor Obelisk had already been placed in the Place de la Concorde, in Paris).

Things may have been different if young Dosios had succeeded to assassinate Queen Amalia in 1861 in this same square (ATHENS 15.12.1863) and maybe then the square would have been named after the revolution. Or even if on February 1863, a few months after the fall of the king, the Greek Montagnards and Girondins did not end the military conflict in February (at least until June), on the way to the Second National Assembly, with a new oath of concord taken in the same square. And if, after the enactment of the new constitution by King George in 1864 [9], the new government had restituted the tributes to the allegedly ‘philhellene’ Otto… If. Eventually, by resolution of the Municipality of Athens in 1884 (Decree 266) that aimed to settle the naming of streets and squares in Athens, the name Omonia Square is established in writing and with it all the changes in the names of squares and streets. The renaming of the extension of Athinas Street beyond Omonia Square, which after its full opening was to be called Athinas (e.g. in Masson’s plan), was also dealt with in the resolution. King Otto Str. and 3rd September (Tritis Septemvriou) Str. appear as possible alternatives. The latter eventually prevailed, although marginally, by eight 8 against 7 votes [10]. It was not considered appropriate to have Otto’s name attached to the square, the name of which was now firmly established in writing as Omonia.

Figure 3: Name changes and semantics of the urban triangle (Source: F. Kafantaris)

In 1884, the first semantic cycle of the planned, though mostly unbuilt, area of Omonia Square closes and the next one opens. This urban core sought its identity in the footprint of its residents as it was moving away from its first significance, more labyrinthine and multilevel, silent or obvious, mounted in the modern reality of the buildings and of the moves of the city around it. Omonia square became a proper name. It became, as often stated, the square of ‘everybody’ as it gradually turned into a general entry point to the centre, the capital, the country. Steam and electric cars came and left, it had an uncovered underground train station and later a covered one, it was the port and railway network terminal of the city, it had intercity bus stations around, buses and even trams. It became a recreation area, hosting crowded cafes and bars, sometimes shops. It was at the core of the hospitality industry with hotels surrounding it for more than a century and a place of any type of meetings, social or political, with overcrowded buildings around it. It was where bloody conflicts, repression, control, demonstrations and celebrations took place; it still is. It is found in poems and film noirs; it became the setting for films with or without a neon background. Omonia Square quickly became a synonym of Athens’ centre, and there, as the words hung on the crowd walking on it, featuring the co-presence of people in the open public space, the square stayed strangely silent and often selectively inhospitable; the field for each type of centrifugal movement. Dictionaries were re-written.

[1] Dickens Ch., (1859 )A Tale of Two Cities, trans. Agapitou A., Trapali V., (1989), Exantas: Athens.

[2] The western part of the square, which nowadays is called Syntagma Square, used to be called for years ‘Kipos ton Muson’ (Garden of the Muses). The name Syntagma Square was referring to the eastern part thereof (int. see Georgiadis Ath. S., 1923 – Second Edition, Athens Plan D.S. of Athens)

[3] For furtrher information regarding this period and the political protagonists see History of the Greek Nation, Volume XIII, chap.: The Greek state from 1862 to 1881, 218- 253.

[4] This plan is generally recorded with date in 1860 [e.g. Biris, K. I. (1966), Athens, (5th 2005, p.112)]. From our investigation until now we conclude that the release date of the project is in 1863 according to the annual publication of the Royal Institute of British Architects/ RIBA in 1864 (Papers – Session 1863-1864, London: RIBA, p.25) with the note ‘the most recent map of Athens from topographical print(sic) ‘. Emmanouil Kalergis is the son of Dimitrios Kalergis, leader of the 1843 revolution and ambassador in France. This relationship might leave room for more assumptions where appropriate.

[5] AION newspaper on5.9.1851 tentatively calls, for the first time, the square in front of the palace as ‘the so-called Syntagma Square’. In previous issues it is referred to as ‘Anaktoron Square’. By this we shall assume a gradual introduction and acceptance of the new name.

[6] Reg. the French Revolution and the founding of the French Republic in particular see Lefebvre, G. (2003 Books 3-5)

[7] The Message of Napoleon on 24 Brumaire (14.11.1799) states: ‘France needs something great and lasting. Instability led it to loss; it is seeking stability. It does not desire the monarchy, this has been proscribed. ” Lefebvre, G. (2003, 596)

[8] On the denominations of the Place de la Concorde see Pugin, A. & Heath, C. (1831, 9) and in Baedecker, K., (1878, 154-155).

[9] For more information, see History of the Greek Nation, Volume XIII, p. 224. Kyriakidis in its Historia, recapping the events of this period, calls such trends to copy the French revolution ‘childish’ while adding and underlining the obvious loan of the names of the two political factions; Montagnards (Ορεινοί) and Girondins (Πεδινοί). Kyriakidis, Ε.Κ. (Κυριακίδης 1892, 221). The Mountain members used to call Valley (Πεδιάδα) or Swamp (Βάλτος) the conservative members of the parliament that denied to align themselves to one party. Lefebvre, G. (2003, 858)

[10] Municipality of Athens, Athens Municipality Historical Archive, Proceedings of City Council, 29th Session/17-01-1884, No. 266 Act of City Council.

Entry citation

Kafantaris, F. (2015) Omonia square: from space to words, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/omonia-concorde/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.19

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Lefebvre G (2003) Η Γαλλική Επανάσταση. Μαρκέτος Σ (επιμ.), Αθήνα: ΜΙΕΤ.

- Γιακουμής Χ και Ανδρέου Τ (2014) Μεταμορφώσεις των Αθηνών: Φωτογραφικό Οδοιπορικό από τον 19ο στον 20ο αιώνα. Καραστάση Α (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Kallimages.

- ΕΤΒΑ (1991) Στατιστική της Ελλάδος, πληθυσμός του έτους 1861. Αθήνα: Πολιτιστικό Τεχνολογικό Ίδρυμα ΕΤΒΑ.

- Κορρές Μ (2010) Οι πρώτοι Χάρτες της πόλεως των Αθηνών. Κορρές Μ (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Μέλισσα.

- Κυριακίδης Ε (1892) Ιστορία του Σύγχρονου Ελληνισμού, Τόμος Δεύτερος. Αθήνα: Ιγγλέσης.

- Μπίρης Κ (1966) Aι Αθήναι από του 19ου εις τον 20ον αιώνα. Αθήνα: Έκδοσις του Καθιδρύματος Πολεοδομίας και Ιστορίας των Αθηνών.

- Συλλογικό Έργο (1977) Νεώτερος Ελληνισμός 1833-1881. Στο: Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, Αθήνα: Εκδοτική Αθηνών.

- Aldenhoven F (1837) Plan topographique d’Athènes et de ses environs. Lithographie royale.

- Fauvel L-F-S (1870) Plan d’Athènes. Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Cartes et plans, GE D-17297.

- Kalergis E (1870) Athènes et ses Environs:Plan topographique d’Athènes et de ses environs. Paris: Imprimerie Lemercier.

- Pugin A and Heath C (1831) Paris and it’s Environs. London: Jennings and Chaplin.

Maps

- Aldenhoven F. (1837), Plan topographique d’Athènes et de ses environs [Archive: Harvard Maps Collection, 011373901]

- Les Officiers du Corps d’ Etat-Major, (1852) Carte de la Grece: Plan d’Athènes, Paris [Archive: DHKI et EKT]

- Kalergis Ε. (1860), Athènes et ses Environs:Plan topographique d’Athènes et de ses environs [National Historical Museum, Archive of Maps, Number Ent. 10627, ATT/26]

- Fauvel L. F. S. (1870), Plan d’Athènes [Αρχείο: Bibliothèque nationale de France, GE D-17297]

- Cleanthis St. and Scahubert E. (1831-1832), Topographic plan of Athens [Archive: 1st Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities] cited in Korres M. (2010), The first maps of the city of Athens, Melissa: Athens.