The development in the neighborhood of Dourgouti since 1922

Myofa Nikolina|Papadias Evaggelos

Housing, Quartiers

2016 | Nov

Dourgouti neighborhood

Dourgouti is a neighborhood that belongs to the City of Athens and specifically to the Neos Kosmos district (ΦΕΚ80Δ 4/2/1988). According to older residents (descendants of refugees from Asia Minor and internal migrants who themselves or their ancestors settled during the period 1922 to 1974), within the limits of the neighborhood one has to include the slum and the so called “Italika“. However, the neighborhood suffered major changes and acquired its present form in the mid-1970s.

Dourgouti is located in a very central point, 2 km from the center of Athens, Syntagma Square, and is easily accessible since many buses pass through Syggrou avenue. Moreover Dourgouti is served by the Metro network (stop “Neos Kosmos“) and the tram network (stops “Kasomouli” and “Neos Kosmos“). Also within the bounds of Dourgouti or in a small distance from this there are some uses of wider metropolitan importance which interact with the neighborhood such as the Intercontinental Hotel, Ethniki Asfalistiki, the Onassis Cultural Center and the Panteion University.

The movie “Magic City”

In 1954 the famous Greek director Nikos Koundouros filmed “his Magic City” in Dourgouti (Thanos 2015). Some of the characteristics of the neighborhood that newspaper reports (Photos 1 & 2) of that time mentioned for Dourgouti, are present at that movie. In particular, one can find there the shacks that were built next to each other resulting to a labyrinth-like structure of the neighborhood [2], the issue of space adequacy, the issue of lack of privacy since the public space was not sufficiently separated from the private as well as the sense of solidarity and mutual help among residents.

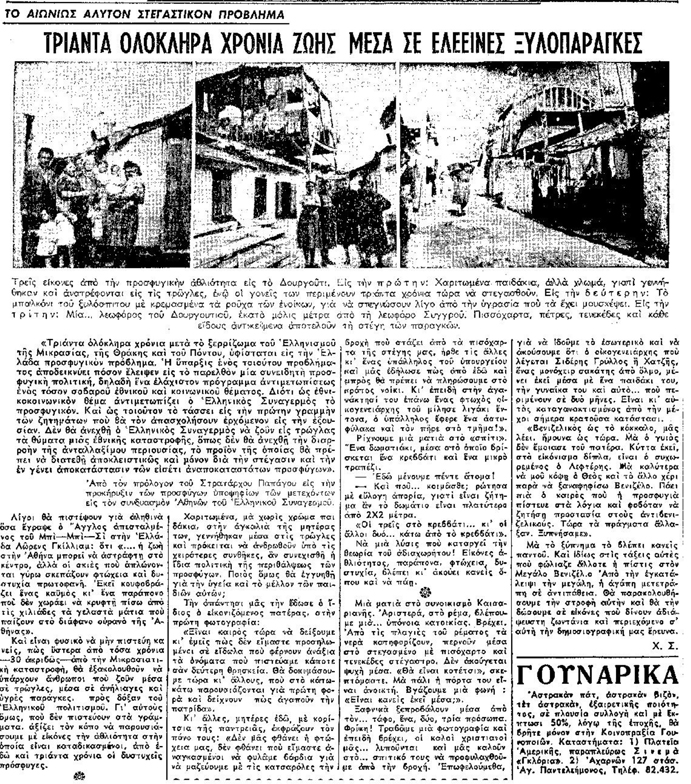

Photo 1: Newspaper article TA NEA, “Research in settlements. The needs of Dourgouti” (4/11/1948, 3)

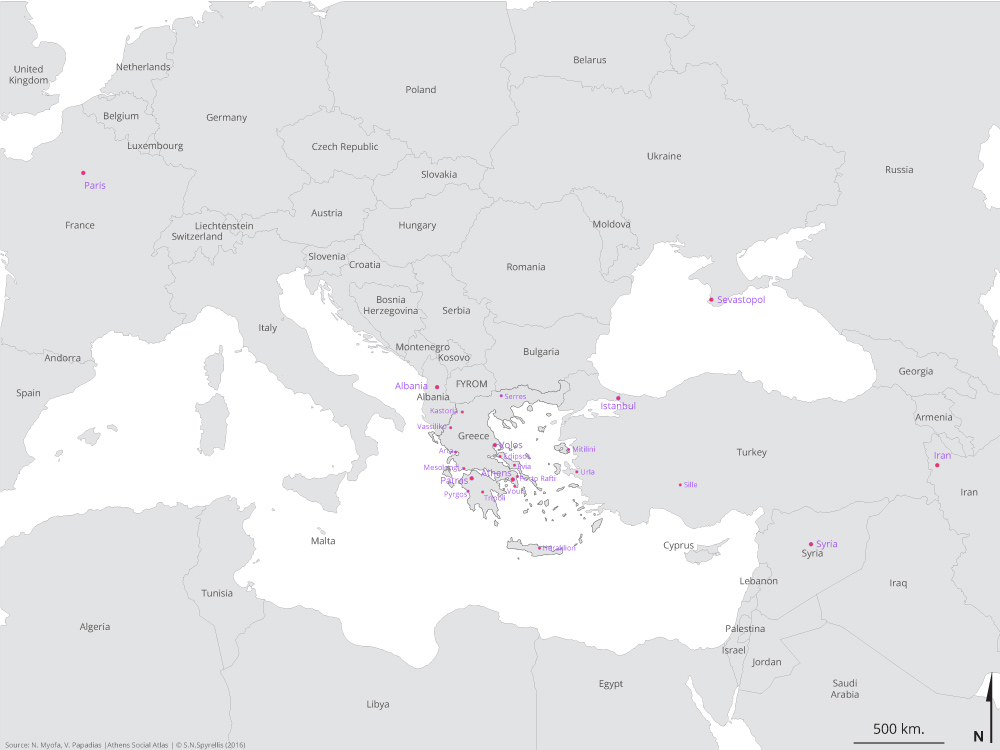

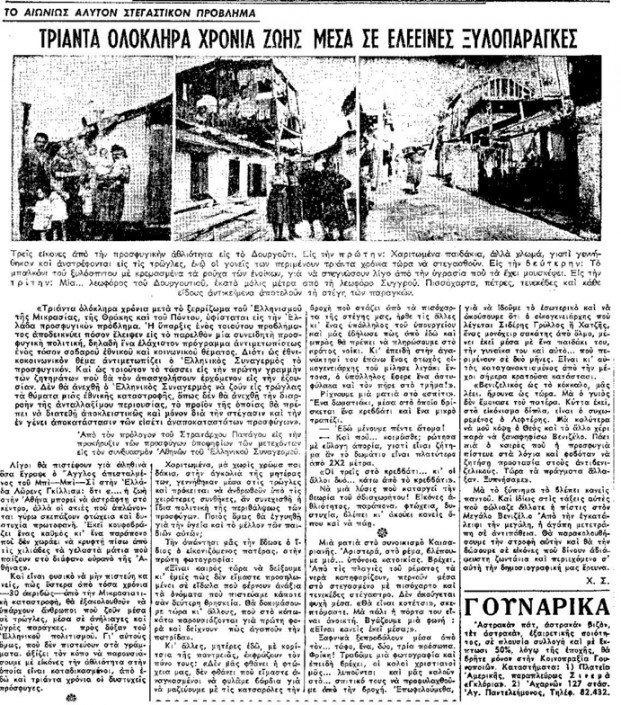

Photo 2: Newspaper article TO VIMA, “The eternal unsolved housing problem. Thirty whole years living into wretched shacks” (8 /11/1952, 3)

The etymology of Dourgouti designation

According to the prevailing view, the name Dourgouti came from an Athenian family Dourgouti or Dourouti [3] who had owned land in the region (Zacharakis 2016). According to a resident the name of the neighborhood may be due to the manufacturer, founder of silk factory in Metaxourgeio, Dourouti who had estates in the region (Θάνος, Νικολαϊδης 2013).

The first settlers and the refugee character of the neighborhood (1920-1949)

Dourgouti is one of the settlements that were created “arbitrarily” in the early 1920s, in the sense that they were constructed by the refugees themselves, outside the official city plan. The refugees who did not have the financial ability– to be quartered either in homes (made of wood, brick) or in some of the refugee settlements [4] that were built by the state and its institutions [5], – settled in Dourgouti waiting the future inclusion of the area into the city plan [6] (Μπίρης 1999, 286, 322).

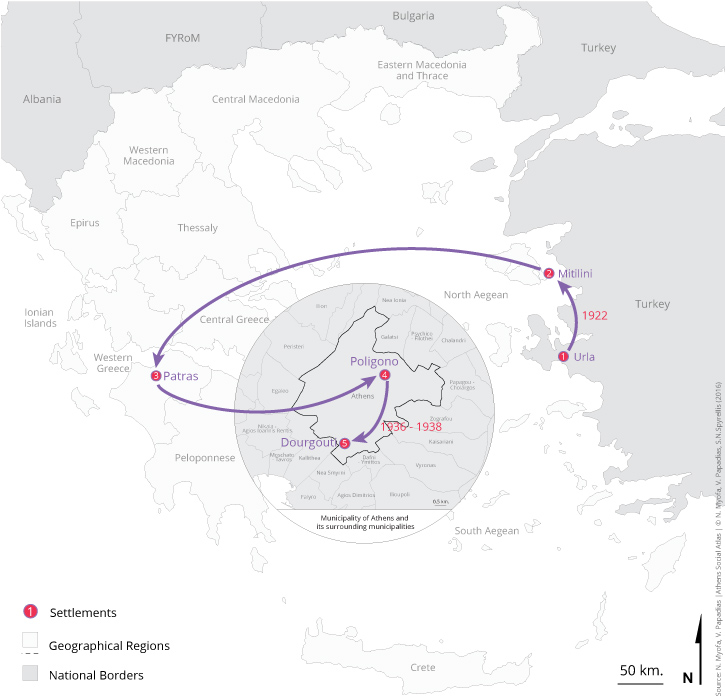

The first residents were Armenian refugees who resorted to Greece just before the Asia Minor Catastrophe. Before refugees settlement, the area was almost uninhabited and there were only farms (Photo 1). The Armenian element was maintained although many Armenians left for various reasons in the 1930s from the neighborhood towards the former Soviet Republic of Armenia (Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Πάπυρος Λαρούς Μπριτάνικα, 1986/1996, 299). The main reasons of the Armenian association with the area is of course the fact that the first residents of the neighborhood were Armenian refugees and also the foundation of the Armenian Catholic Church in 1925, which helped maintain the links that they had developed with the neighborhood (Αντωνίου 1995, 98).

In 1922 due to the Asia Minor Catastrophe in Dourgouti Greeks from various regions of Asia Minor (Smyrna, Aivali, Sully, Trapezounda, Sampsounta, etc.) but also from Constantinople settled in Dourgouti. The settlement of refugees in the area was not organized, because the shacks were built arbitrarily and not in the base of a design. In fact wherever there was empty space the refugees themselves used to build a shack. New waves of refugees continue at least until 1928. The result of this was the continuous expansion of the boundaries of Dourgouti with the construction of new shacks and the creation in a very short time of an entire settlement of shanty houses (a slum) (Παπαδοπούλου και Σαρηγιάννης 2006, 56-58, Leontidou 1989/2001, 156).

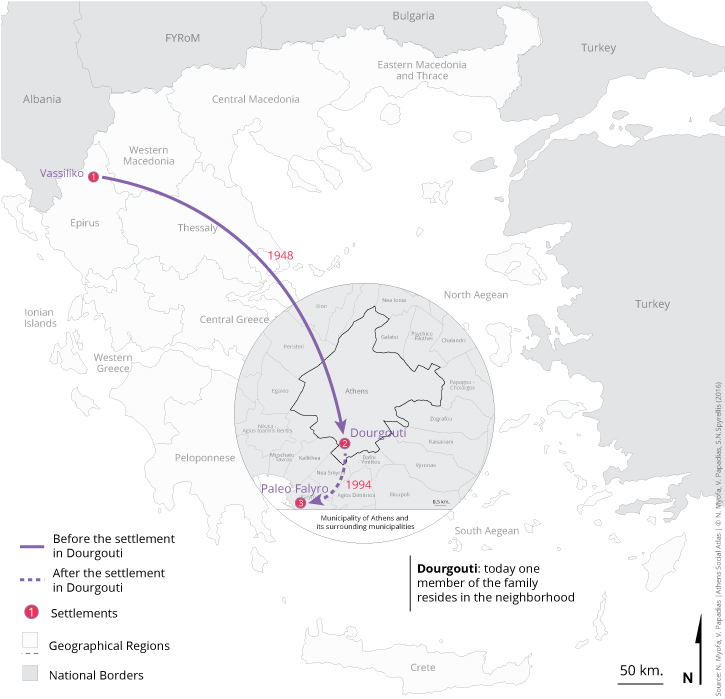

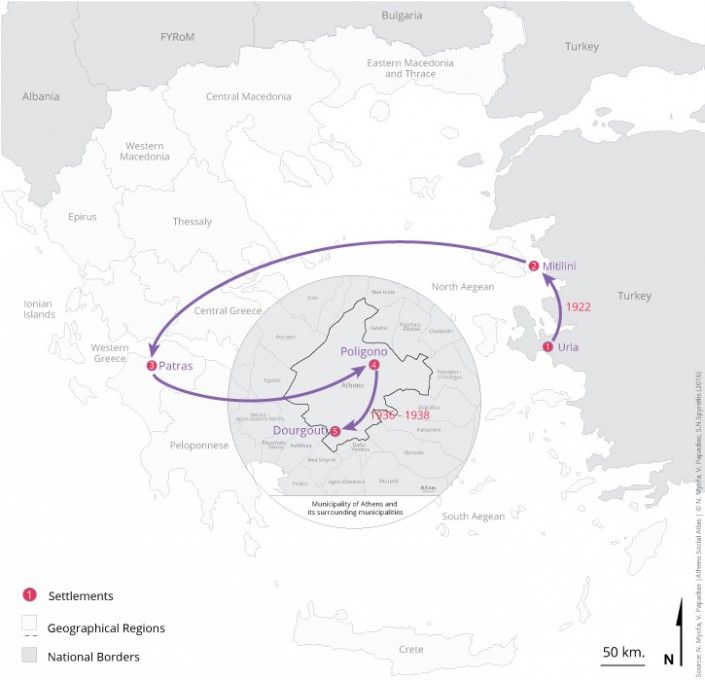

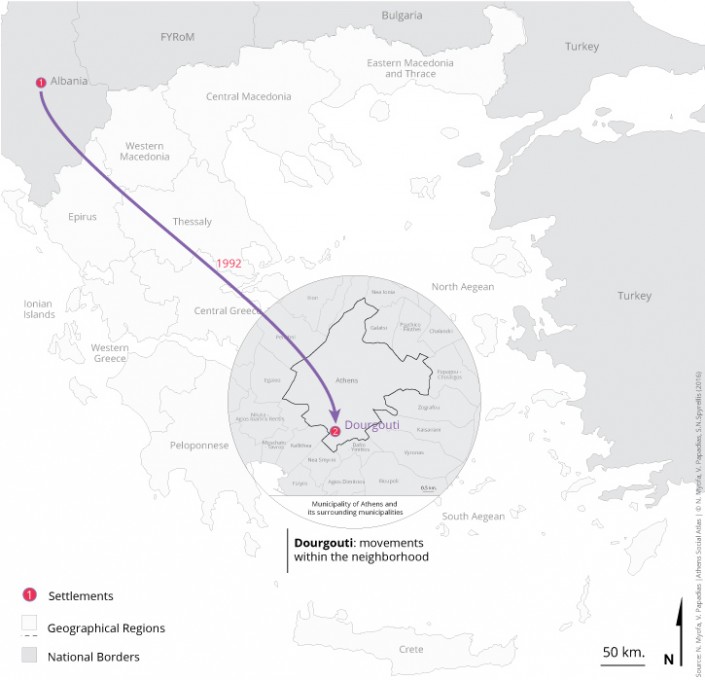

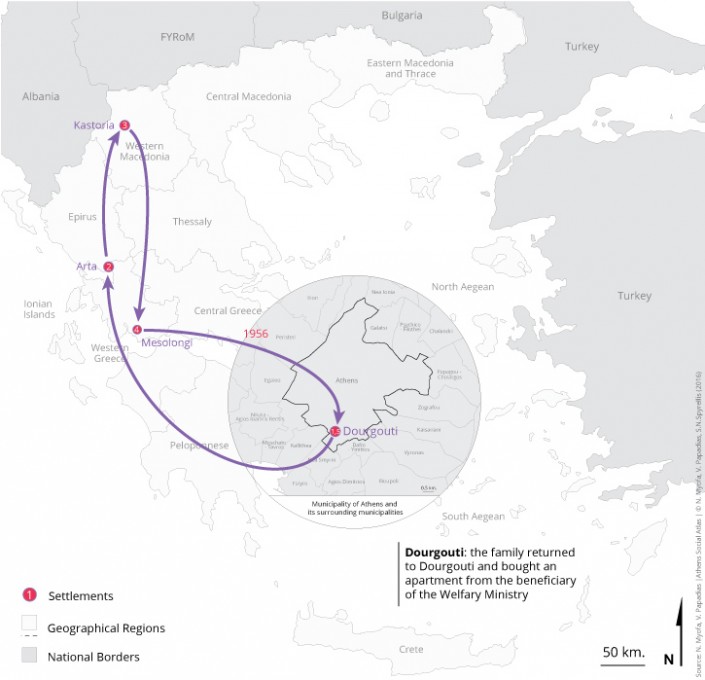

Map 1: Residents settlements

The first organized constructions the “Italika” and subsequently refugees apartment blocks of Welfare Ministry.

The “Italika” buildings were built in 1924 with money paid by Italy to Greece as war claims and so they took their name [7]. They were a group of 24 single-storey houses in 6 rows. Approximately 100 families of refugees from Asia Minor (Greeks or Armenians) settled there (Θάνος, Νικολαϊδης 2013 & Μεγάλη Ελληνική Εγκυκλοπαίδεια, 386).

The “Italika” was stone-built and according to residents’ narratives they were better constructions compared to those in the shantytown. However the socio-economic profile of those who lived in these houses did not differ from that of the residents in shacks.

Since the mid-1930s the Welfare Ministry made a first attempt at clearing the settlement of the shacks with the construction of eight apartment blocks (Photos 3-5). According to Vassiliou (Βασιλείου 1944, 83) “Dourgouti with interesting constructions is the largest center with apartment buildings for refugees” [8]. These blocks are the first ever constructed in the neighborhood and they constitute the group of the old apartment blocks of Dourgouti the neigborhood (Map 2). Despite the fact that some shacks were demolished, in order for the rebuilding to take place, there were still several shacks next to apartment buildings(Βασιλείου 1944, 78).

Photo 3: The first 4 of the apartment blocks for refugees that were built during the period 1935 to 1936 (Source: Myofa N. 2016)

Photo 4: This apartment block for refugees was built during the period 1938 to 1940 (Source: Myofa N. 2015)

Photo 5: This apartment block for refugees was built during the period 1938-1940 (Source: Myofa N. 2015)

Map 2: Relocations of one family of refugees from Asia Minor (narrator’s grandparents) from 1922 to 1940 (1st and 2nd generation). Settlement in the neighborhood, before the outbreak of the Second World War

Settlement of internal migrants at Dourgouti (1950-1974)

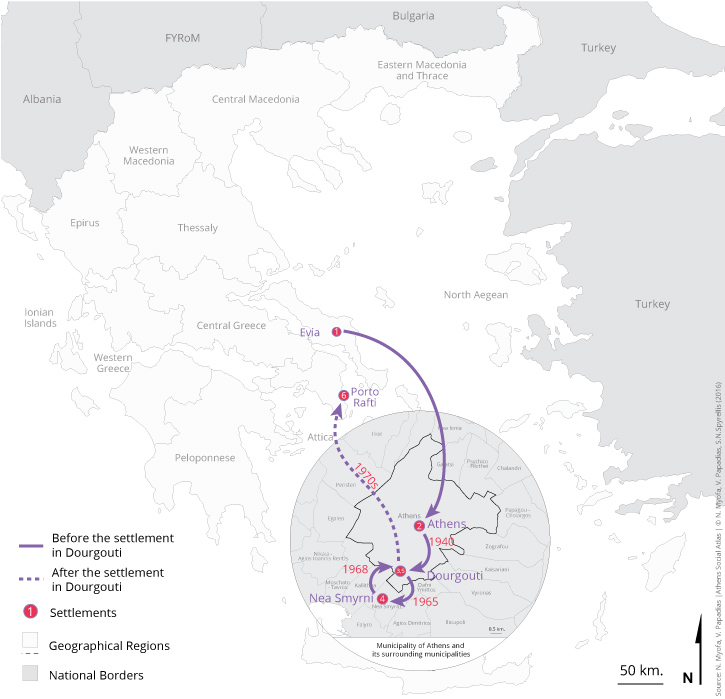

In the period from the end of Civil War until the early 1970s urbanization rates were very intense. Populations from different places of Greece abandon the rural areas for various reasons (civil war, job searching, etc.) and settle in the cities, especially in Athens (Maloutas 2003, 98). Natives from Ioannina, Evia, Ilia, Messinia, etc. seek for a shelter at Dourgouti (Maps 3, 8, 14). The new populations were being housed in shacks that had been abandoned from previous settlers mostly Armenians:

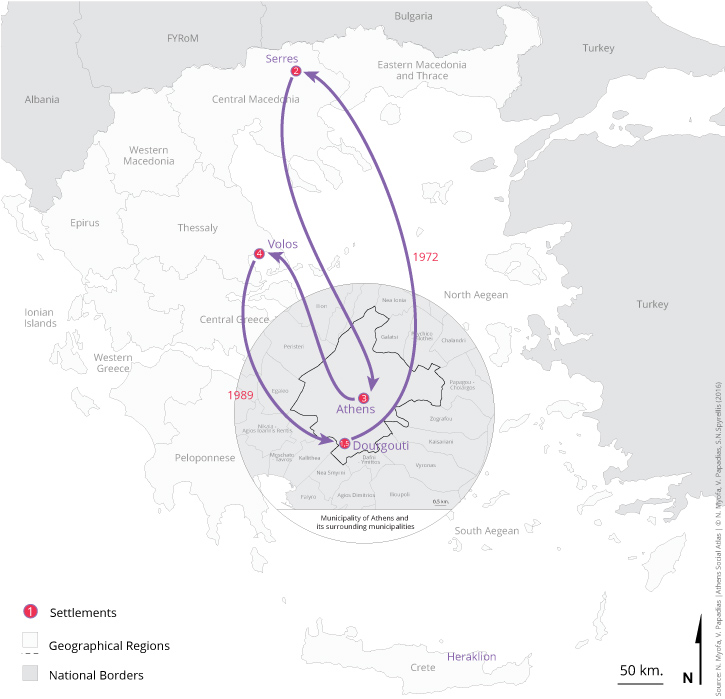

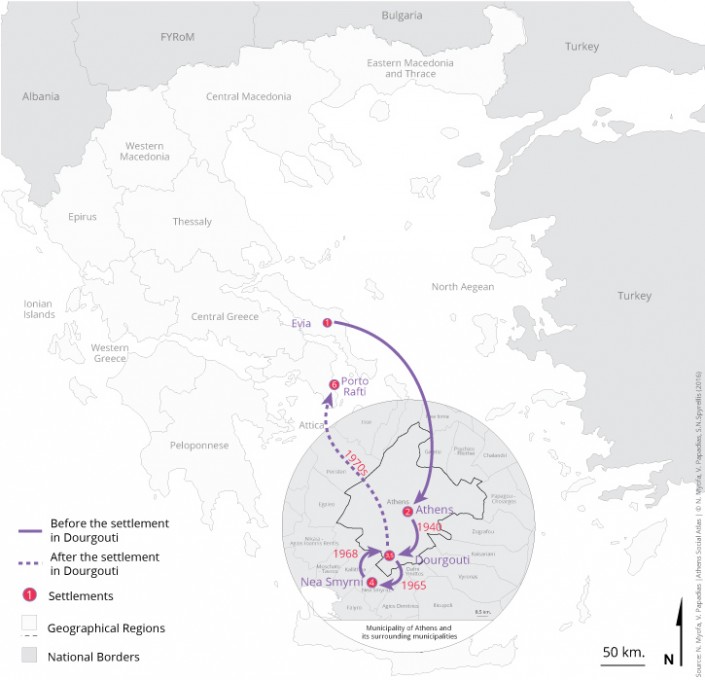

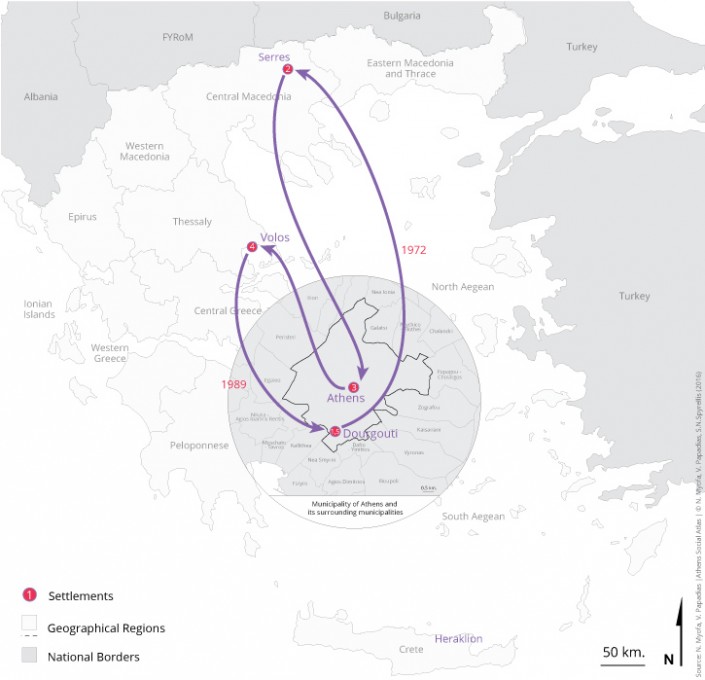

Map 3: Relocations of one family of internal migrants from Evia and settlement in a shack at Dourgouti. During the period of apartment buildings construction they relocated to Nea Smyrna and then returned to the neighborhood (1st and 2nd generation). The parents left from Dourgouti, after they had rented the apartment, in the 1970s, and settled in Porto Rafti

| “And then, an opportunity appeared, as an Armenian told [to my father] about a shack, that belongs to his relative who was going to leave for America, to buy it and to be close to each other. And indeed he bought for a very small amount. We hadn’t even seen it. We carried everything with a truck of that time, three wheels, and went. The first thing I saw was the number…” (Matina 10/12/2014). |

But the social profile of the neighborhood does not change because the internal migrants are also poor people:

| “Meanwhile, because there was poverty all around, they [migrants] were coming. They had already listened about Dourgouti, “lets go, there are houses to stay there.” And so poor men were coming, they were “sneaking” in a shack, not paying a rent […] and everbody who found the opportunity and could with the help of each other- with the help of each other everything got occupied! Armenians had not yet all gone” (Christina 3/11/2015). |

This continuous alternation of population in shacks was the reason that the program of shacks’ demolition and construction of new homes, for families that lived in, took so much time to be implemented (Παπαϊωάννου 1975, 56-57).

Program of “shantytown’s regeneration” in Dourgouti: Construction of public housing apartment blocks

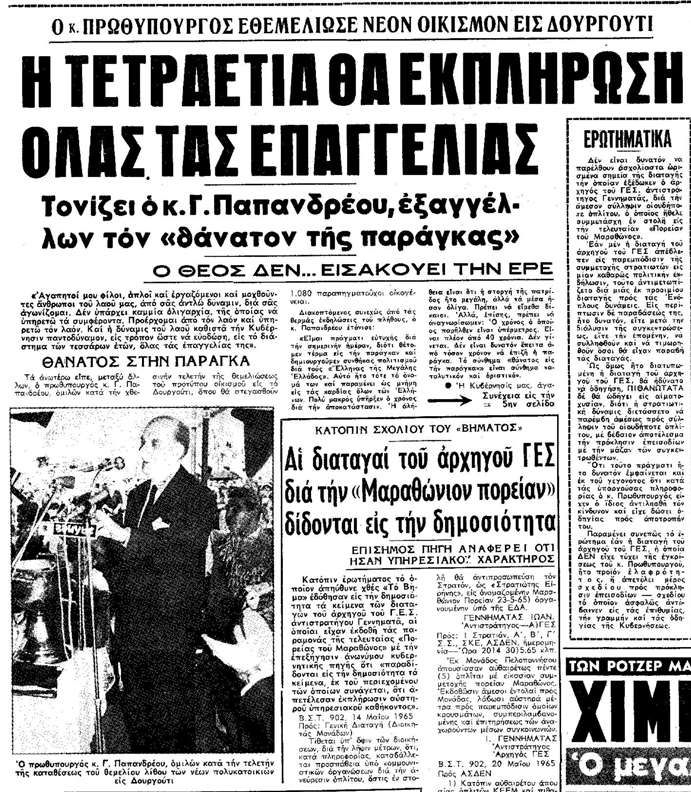

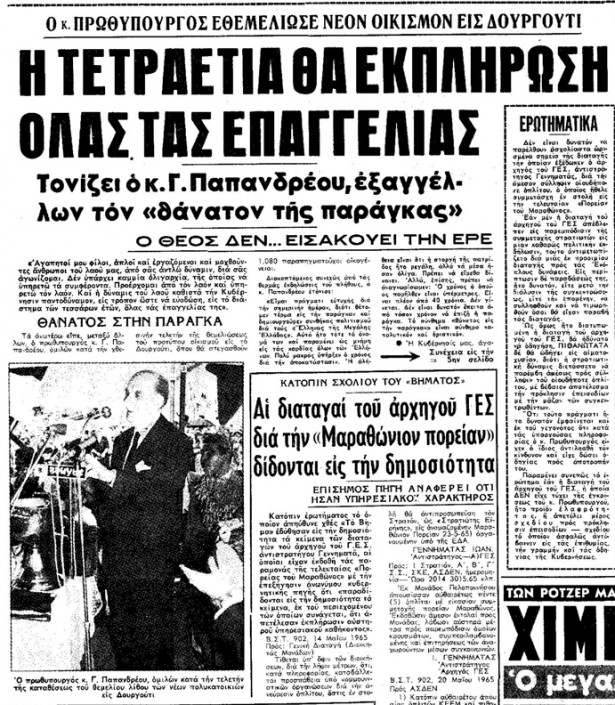

Prime Minister George Papandreou with the slogan “Shacks’ death” in 1965 laid the foundations for apartment’s block construction at Dourgouti (See video with this particular issue by the Hellenic National Audio Visual Archive) with the demolition of shacks and “Italika” for housing refugees and internal migrants (Photo 6).

Photo 6: Newspaper article TO VIMA, “The Prime Minister founded a new settlement in Dourgouti” (10/6/1965, 1)

The implementation of the final program of the Welfare Ministry in the area began in 1967 and ended in 1971, in the period of dictatorship. According to residents of the neighborhood a census of residents at the shacks was preceded. The distribution of the 865 apartments to beneficiaries became after a draw that was taking into account the number of members of each family (Παπαϊωάννου 1975, 59, 83). It is noteworthy that, the construction of 12-storey building (Photo 7) has symbolic value because “this construction closes the issue of housing refugees“.

Photo 7: The 12-storey building at Sfiggos 8 street is the last construction of public housing that was built by the State for those who lived in shacks (Source: Myofa N. 2015)

This transition from shacks to apartment buildings despite the fact that it meant better housing conditions for residents, it brought about significant changes in other characteristics such as neighborhood’s social cohesion and the sense of solidarity among residents. One resident describes the changes that occurred in the neighborhood:

| “They changed since, the demolition of all of them and the construction of the apartment blocks, they came from Tavros here, from Kountourgioti […]And from Drapetsona […] And as you understand they had not the same outlook on life. The neighborhood broke down after that, spoiled!” (Vlasis 22/11/2014). |

As for Armenian refugees they did not belong to the apartment beneficiaries with the particular state program. Those who were not housed in a 4 storey building at the street Rene Puo 2 (Photo 8)- that was built with the assistance of the Armenian Catholic Church in 1958- relocated to other refugee neighborhoods at Karea, at Nea Smyrni and elsewhere in the greater Athens area (Αντωνίου 1995, 107).

Photo 8: The building of Rene Pyo 2 street was constructed to house the Armenians refugees who lived in shacks. Today apart from older residents also Armenians, who settled in the neighborhood over the next decades, housed there (Source: Myofa N. 2016)

Dourgouti today

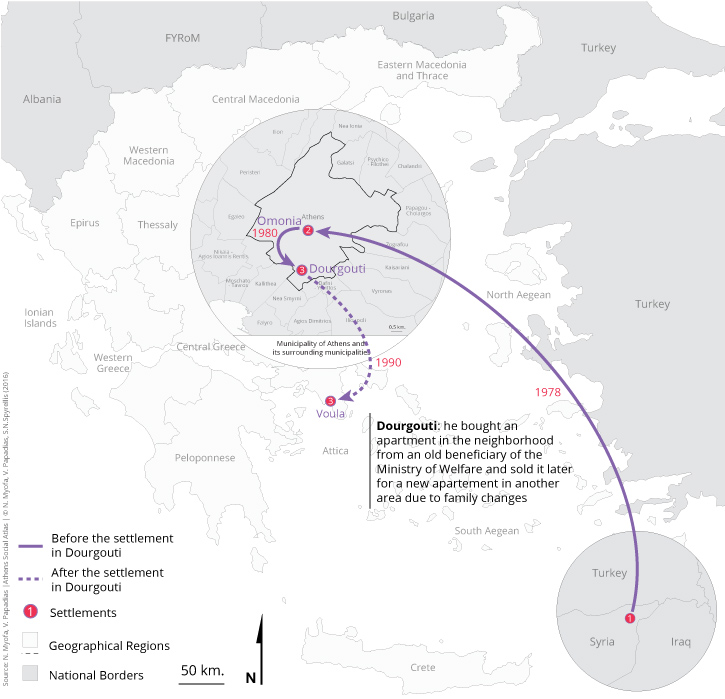

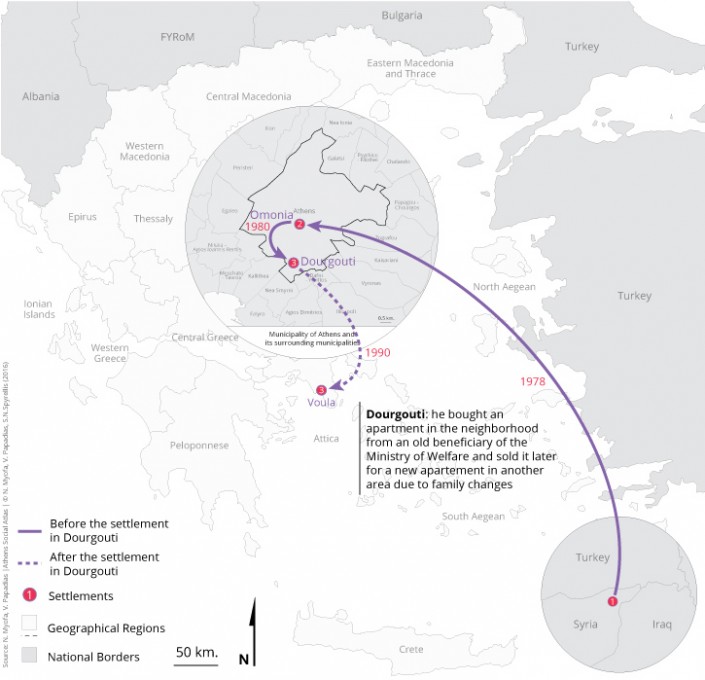

Since the early 1980s new residents’ inflows in Dourgouti are observed, not as intense as in the previous period. New residents are– either Armenians from Syria, Iran, Livanon, or internal migrants from various parts of the country– settled in apartments they buy or rent from the owners, former beneficiaries of the Welfare Ministry. The new wave of Armenians (Maps 4 & 5), of this period, are settled in Dourgouti because of the strong hostorical ties with the neighborhood.

Map 4: Relocation of one family of Armenians from Iran directly to Dourgouti in 1986

Map 5: Relocations of an Armenian from Syria to Omonia and then to Dourgouti. Settlement in another area, Voula, due to family changes

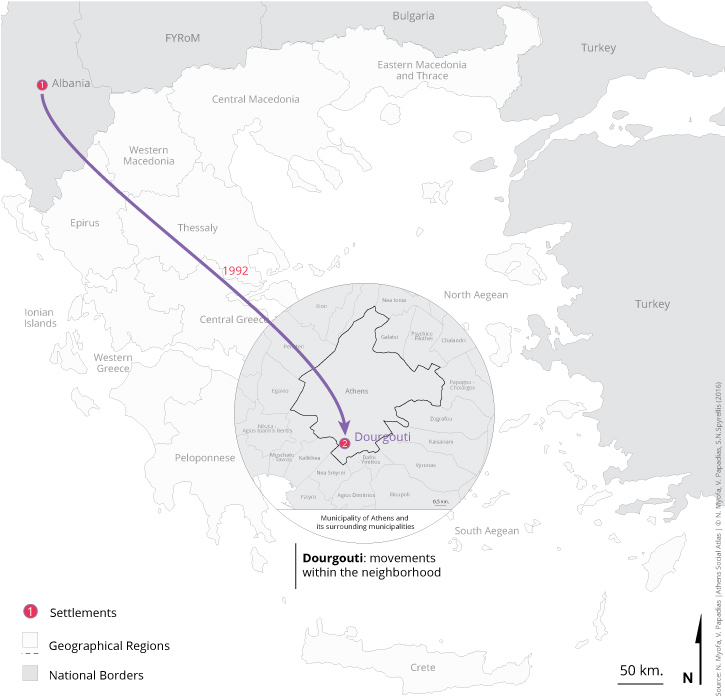

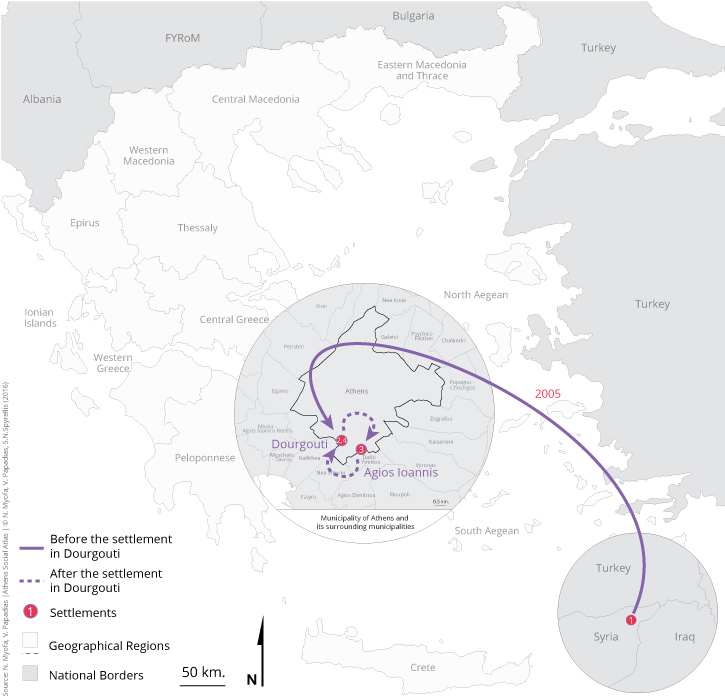

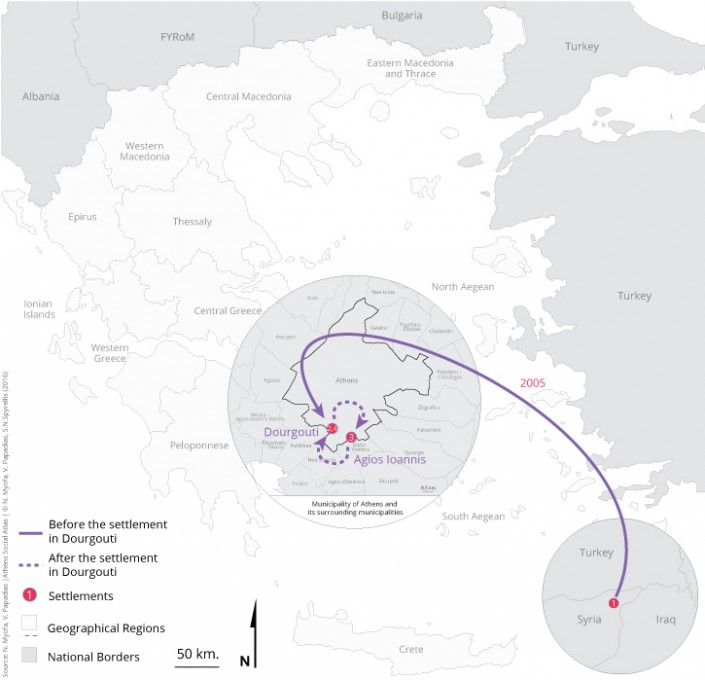

Also since the mid-1990s the inflow of foreign migrants– from Syria, Albania, Bangladesh– in the area increases. Those most recent residents are called by the old ones “new-immigrants“, a name that shows the intensity and continuity of the migratory waves that the neighborhood has received. They choose Dourgouti as a place of residence and specifically an apartment in the old refugee blocks due to low rent. Furthermore they settle in Dourgouti because usually someone from their family or a familiar person or a friend already lives in the neighborhood. This applies particularly to the Syrians and Albanians that as being seen have developed strong networks in the region and are usually settle directly in Dourgouti (Maps 6 & 7). However their settling there, can be either for a short time or for a more permanent amount of time. A resident describes the situation as follows:

Map :6 Relocation of one family of migrants from Albania to Dourgouti in the 1990s

Map 7: Relocation of one migrant from Syria directly to Dourgouti in 2005. He left from Dourgouti for a while and returned again in 2011

| “[The neighborhood] has people who will be one–two in fact to whom the house belongs and then 5–10 pass by within one year because they are familiars– friends– relatives who will stop for maybe two days in Greece and then hit the road” (Manolis 3/6/2015). |

Today Dourgouti concentrates a dwelling stock (public housing apartment buildings for refugees and internal migrants) which is aged and due to inexpensive rents tends to attract economic migrants. But without this to be the rule, since there are many descendants of Asia Minor refugees and of internal migrants 2nd, 3rd and 4th generation who reside in the neighborhood (Maps 8, 9, 10).

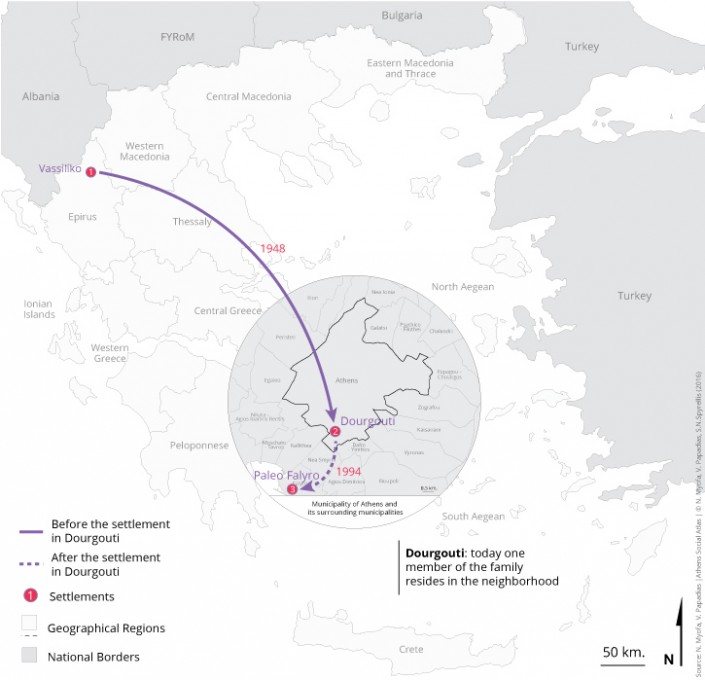

Map 8: Relocations of one family of internal migrants from Ioannina to Dourgouti in 1948 (1st and 2nd generation). The narrator said that, he created an autonomous household and then relocated to another area

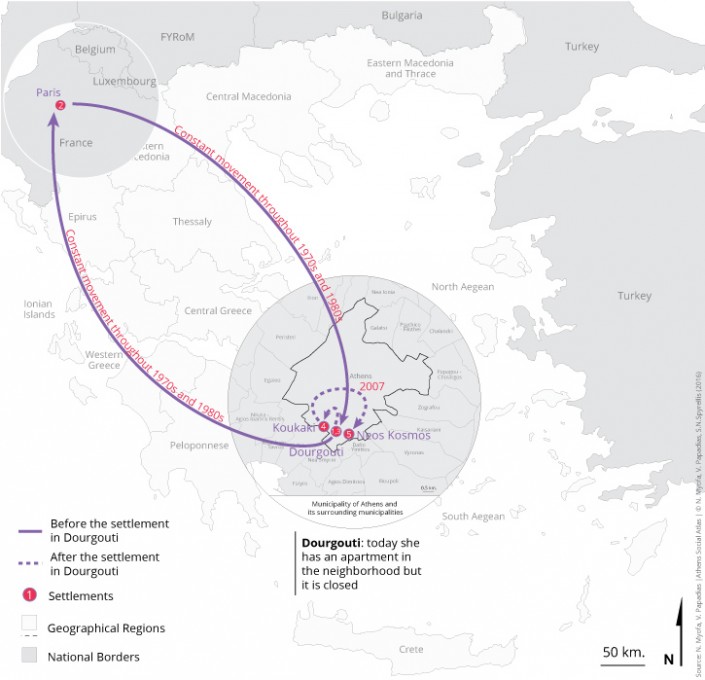

Map 9: Relocations of the narrator since she creates her own family. Settlement in the neighborhood at the end of 1980s

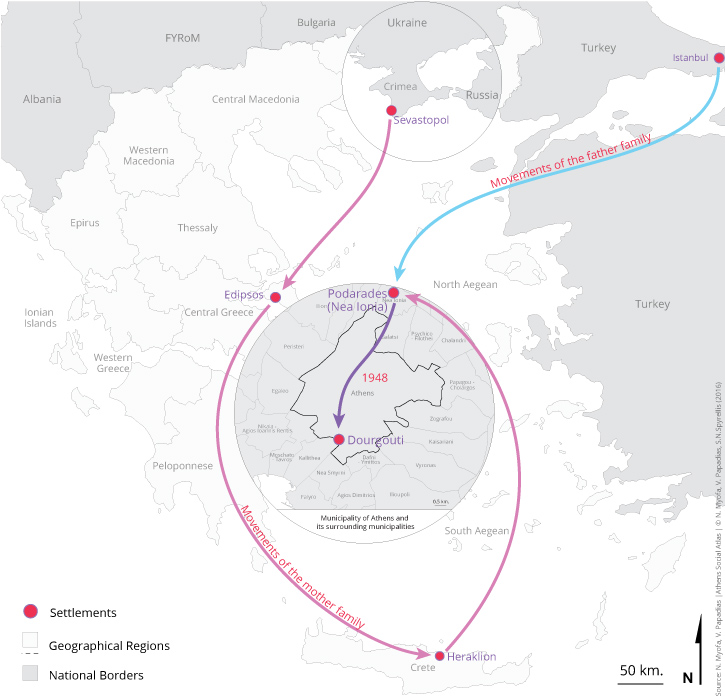

Map 10: Relocations of two families of Armenian refugees (father’s family and mother’s family of narrator) from Sevastopole and Constantinople to Nea Ionia during the period from the early 1920s to 1940s. Then the children of the family (narrator’s parents) created an autonomous household and settled in Dourgouti (1st and 2nd generation)

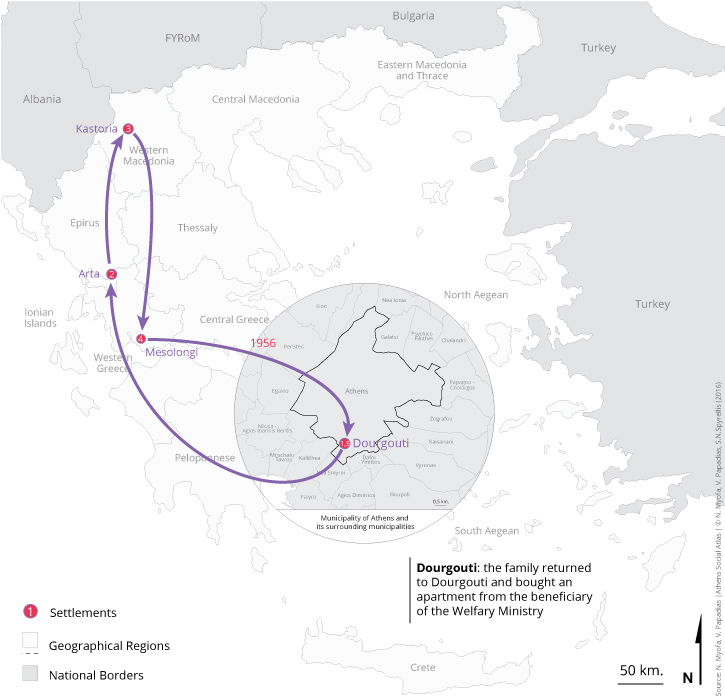

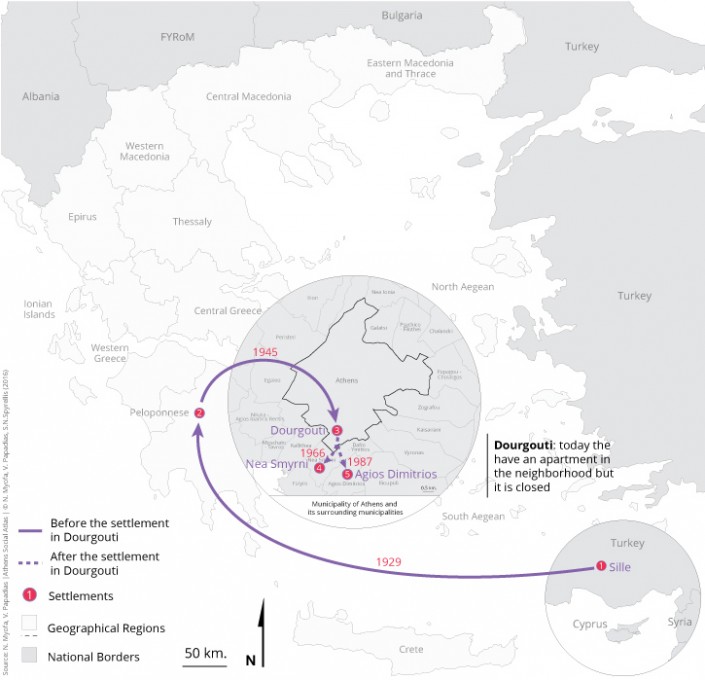

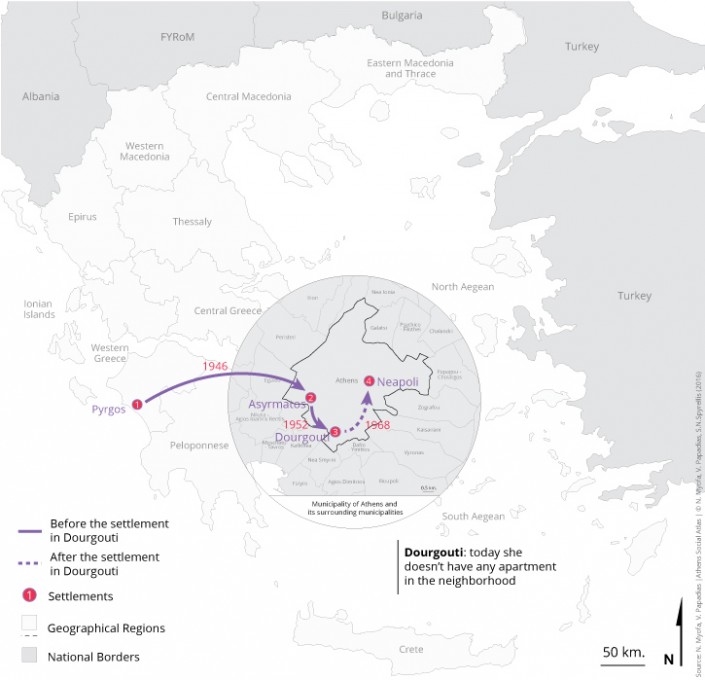

The residents are mostly owners of their apartment which they acquired by inheritance. The reasons they choose to continue to live there are very practical and have to do with the fact that in the neighborhood is located their home but are also emotional and associated with the ties residents have developed with the neighborhood and the other inhabitants. Also there are the cases of those who have an apartment in the neighborhood, but they don’t reside there anymore and either they have closed it (Maps 11, 12, 13) or rent it or the apartment was given to relatives (Map 14).

Map 11: Relocations of the narrator with her parents from Dourgouti in other areas. Settlement in the neighborhood in the mid 1950s (2nd and 3rd generation)

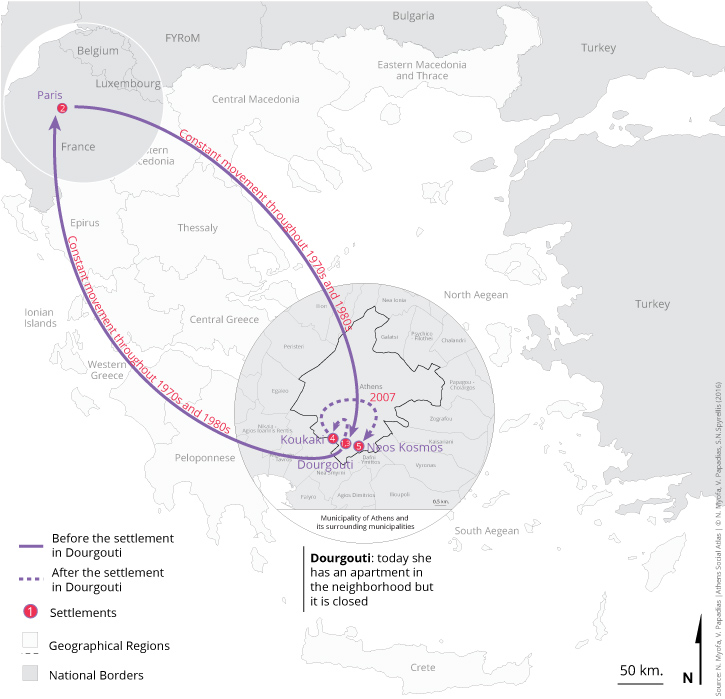

Map 12: Relocations of the narrator from the 1970s until 2007 (3rd generation)

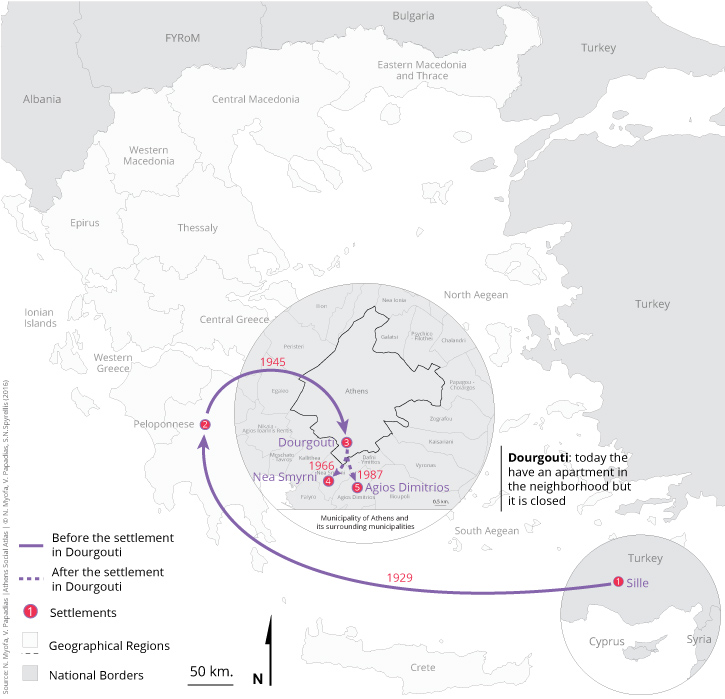

Map 13: Relocations of one family of refugees from Sully in Asia Minor (1st generation). The two children of the family created autonomous households and relocated to other areas

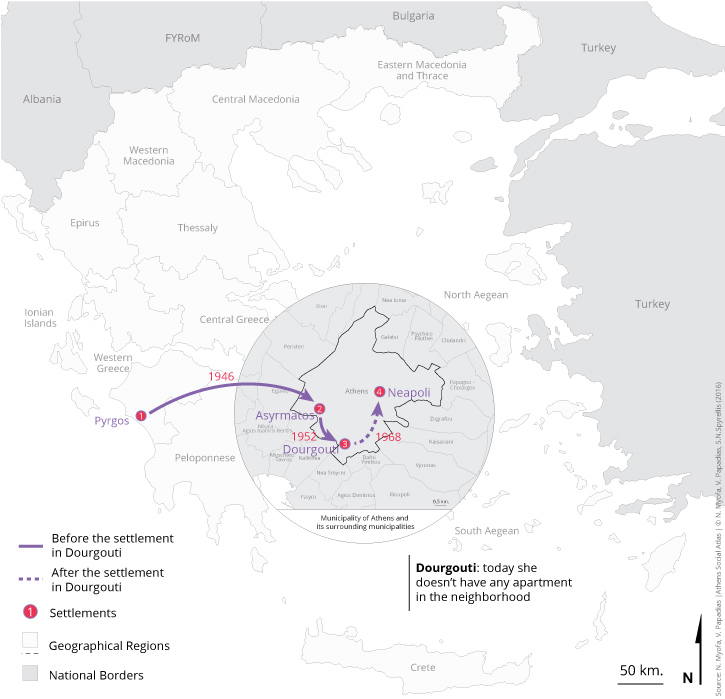

Map 14: Relocations of one family of internal migrants during the period 1946-1952 from Pyrgos Ilias to Dourgouti and from Dourgouti to Neapoli in 1968 up today. The narrator said that, today she doesn’t own any property in the neighborhood

The coexistence between natives residents of the neighborhood and immigrants who settled in the last decades maintained in a rather normal level. Maybe it has to do with that– Dourgouti was– a neighborhood which always had intensive refugee and migration flows:

| “Certainly those Albanian families who settled here and stayed, became completely acceptable, let’s say[…]. In fact they were not assimilated by us […] we learned to live with each other and to find out, you know, the middle way, let’s say, so that we were able to understand each other” (Evaggelia 5/5/2015). |

| “Well there, sometime, maybe three or four years ago some Syrians had resided. Okay […] they made some constructions around the house […]. So in the summer, they came out, they took out tables and the shisha and they sat […]. It was too picturesque! I was thinking: “How nice, like it used to be. As I have heard from older people’s narratives that in the summers they slept on the rooftop and they did not shut their eyes until next morning” (Aggeliki 5/5/2015). |

In conclusion Dourgouti is a neighborhood with an intense migratory history that even today continues to accept new waves of migrants and refugees. The apartment buildings that were built by the state for those who– refugees and internal migrants– could not afford to be housed by their own means, nowadays accommodate new-immigrants and also descendants (children or grandchildren) of older residents of the neighborhood who continue the history of Dourgouti .

Mapping senses and elements of history

Web mapping has revolutionized the field of cartography. Cartographers tend to have more and better digital tools available for space representations and data visualization, while everybody gain increasingly more access to simple mapping applications and techniques.

History mapping web application attempt, accessible by the link below, consists of representations of 2-dimensional urban terrain tranformations(at years 1929,1940,1959 and 2014), events occured during German occupation period in Athens and use of buildings, documented by oral testimonies, illustrations of the neighborhood in old photos and cinema films, locating their shooting spots, as well as some major landmarks from the past ( http://dourgoutihistory.comuf.com/ ).

Προκειμένου να δημιουργηθεί ένα ολοκληρωμένο αφήγημα, αλλά και να αναδειχθεί κατά το δυνατόν μεγαλύτερο μέρος από το πολιτισμικό κεφάλαιο που έχει δημιουργηθεί στο Δουργούτι, εκτός από την χαρτογράφηση της Ιστορίας, επιχειρήθηκε και μια ιδιόμορφη χαρτογράφηση, με στόχο να διερευνηθεί το παρόν, όχι όμως μέσα από την ματιά ενός παρατηρητή-μελετητή, αλλά από τη σύνθεση απόψεων και σχολίων που διατύπωσαν πολλοί και διαφορετικοί, κάτοικοι και μη, που αξιολόγησαν το χώρο με αφετηρία τα ερεθίσματα που προκάλεσε στις αισθήσεις τους.

Apart from mapping history, in order to extract quality knowledge and compose a more complete narrative for the neighborhood, a research conducted to study the present situation, not through the eyes of an individual, but through the opinion and comments of many different people living or not in the area. These people evaluated space recording the impressions produced by urban terrain characteristics to their five basic senses. The aim was to reveal diversity and contrasts occured by space.

Data collection was made possible using a questionnaire in the form of a three dimensional map and totally 206 individuals voluntarily participated.

The idea of sensory survey conducted, better known as the “exploration of the neighborhood throughout senses”, belongs to the site-specific art team “ohi pezoume” and specially to George Sachinis [9]. It started in September 2014 and finished in December of the same year.

Data collected primarily in the field, as well as the results, are presented in a form of a web application accessible by the following link: https://veegee.shinyapps.io/sensor/

[1] This article is based on the qualitative research through interviews with residents of the neighborhood that Nikolina Myofa carried out between November 2014 up to February 2015 in the context of the PhD thesis she does at Harokopio University under the title “Social housing in Athens. Study of refugees’ settlements Dourgouti and Tavros from 1922 to nowadays” and the BSc thesis entitled “Historical and sensory mapping to Dourgouti neighborhood in the New World” by Evangelos Papadias.

The authors thank several people who contributed substantially to the production of this document. Firstly the residents of Dourgouti who were interviewed, Mrs. Tasoula Vervenioti scientific responsible of the “Oral History Group of Dourgouti” (OPIDOU) and all the members of the group for the constructive discussions. Also we thank George Sahinis the inspirer of Dourgouti Island Hotel Project because through various actions that carried out in the neighborhood contributed the creation of a dialogue and trust climate with residents and therefore facilitate the completion of the research. Furthermore we thank the members of the “Historical Mapping Group” coordinated by George Thanos who accomplished research in archival and bibliographical sources in order to highlight the rich history of the neighborhood. Finally we thank George Kandylis, researcher at the National Center for Social Research, for editing the text in English.

[2] In old maps of Athens, Dourgouti appeared as the “labyrinthine settlement of Armenians” (Αντωνίου 1995, 104).

[3] For more informations about Dourouti family see Μπίρης 1999, 241.

[4] Vyronas, Kaisariani, Nikaia, Tavros, etc.

[5] Refugee Fund, Refugee Settlement Commission and Technical Service of Welfare Ministry.

[6] In the census which was carried out in 1940 Dourgouti was no longer an independent settlement but it was included in the city plan of Athens (Υπουργείον Εθνικής Οικονομίας- Γενική Στατιστική Υπηρεσία της Ελλάδος 1950, 62).

[7] The Catholic monastic Order of “Saint John of Jerusalem” has undertaken the construction of these houses.

[8] For refugees’ apartment blocks, see Βλάχου κ.α., 1978: 122

[9] The survey was made possible through the collaboration of “ohi pezoume” team and the Department of Geography of Harokopion University during Dourgouti Island Hotel project.

Entry citation

Myofa, N., Papadias, E. (2016) The development in the neighborhood of Dourgouti since 1922, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/dourgouti/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.64

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

Βιβλιογραφία

- Αντωνίου Π (1995) Η Ελληνο-Αρμένικη κοινότητα της Αθήνας. Πανεπιστήμιο Αιγαίου. Available from: http://thesis.ekt.gr/thesisBookReader/id/5015#page/1/mode/2up.

- Βασιλείου Ι (1944) Η λαϊκή κατοικία. Αθήνα: Π.Α.Διαλησμά.

- Βλάχος Γ, Γιαννίτσαρης Γ και Χατζηκώστα Ε (1978) Η στέγαση των προσφύγων στην Αθήνα και τον Πειραιά στην περίοδο 1920-1940. Προσφυγικές πολυκατοικίες. Αρχιτεκτονικά Θέματα 12: 117–124.

- Γκιζελή Β (1984) Κοινωνικοί μετασχηματισμοί και προέλευση της κοινωνικής κατοικίας στην Ελλάδα 1920-1930. Αθήνα: Επικαιρότητα.

- Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Πάπυρος Λαρούς Μπριτάνικα, Τόμος 21ος (1986) Δουργούτι. Εκδοτικός Οργανισμός Πάπυρος.

- Ζαχαράκης Μ (2016) Συνοπτική Ιστορία Δουργουτίου. Available from: http://dourgouti.nkosmos.gr/?p=305.

- Θάνος Γ (2015) Όψεις του Δουργουτίου στην τέχνη και τη λογοτεχνία. Ομάδα Άστυ. Available from: http://omadaasty.blogspot.gr/2015/08/dourgouti-kai-logotexnia.html (ημερομηνία πρόσβασης 27 Αυγούστου 2015).

- Θάνος Γ και Νικολαϊδης Ν (2013) Ο Νέος Κόσμος των Προσφύγων. Ομάδα Άστυ. Available from: http://omadaasty.blogspot.gr/2013/04/o.html (ημερομηνία πρόσβασης 5 Απριλίου 2013).

- Λεοντίδου Λ (1989) Πόλεις της σιωπής. Εργατικός εποικισμός της Αθήνας και του Πειραιά, 1909-1940. 1η έκδ. Αθήνα: Πολιτιστικό Τεχνολογικό Ίδρυμα ΕΤΒΑ.

- Μεγάλη Ελληνική Εγκυκλοπαίδεια, Τόμος ΙΓ (1956) Ιωαννίται. 2η έκδ. Ο Φοίνιξ.

- Μπίρης Κ (1966) Aι Αθήναι από του 19ου εις τον 20ον αιώνα. Αθήνα: Έκδοσις του Καθιδρύματος Πολεοδομίας και Ιστορίας των Αθηνών.

- Παπαδοπούλου Ε και Σαρηγιάννης Γ (2006) Συνοπτική έκθεση για τις προσφυγικές περιοχές του Λεκανοπεδίου Αθηνών. Αθήνα. Available from: http://courses.arch.ntua.gr/fsr/137052/Prosfugika Lekanopedio.pdf.

- Παπαϊωάννου Ι (1975) Η κατοικία στην Ελλάδα. Κρατική δραστηριότης. Αθήνα.

- Τα Νέα (1948) Έρευνα στους συνοικισμούς. Αι ανάγκαι του Δουργουτίου. Αθήνα, 4 Νοεμβρίου.

- Το Βήμα (1952) Το αιωνίος άλυτον στεγαστικόν πρόβλημα. Τριάντα ολόκληρα χρόνια ζωής μέσα σε ελλεινές ξυλοπαράγκες. Αθήνα, 8 Νοεμβρίου.

- Το Βήμα (1965) Ο κ. Πρωθυπουργός εθεμελίωσε νέον οικισμόν εις Δουργούτι. Αθήνα, 10 Ιουνίου.

- ΦΕΚ Δ’ 80 (1988) Έγκριση Γενικού Πολεοδομικού Σχεδίου Δήμου Αθηναίων (Νομός Αττικής). Ελλάδα.

- Maloutas T (2003) The self-promoted housing solutions in post-war Athens. Discussion Paper Series 9(6): 95–110. Available from: http://www.prd.uth.gr/uploads/discussion_papers/2003/uth-prd-dp-2003-06_en.pdf.