Mapping energy poverty in Athens during the crisis

Chatzikonstantinou Evangelia|Vatavali Fereniki

Built Environment, Politics, Social Structure

2016 | Dec

Introduction

One of the new phenomena that have emerged recently in Athens with great intensity is the difficulty of households to have access to adequate energy consumption. Since the outbreak of the Greek debt crisis in 2010 a significant number of households cannot cover their energy needs for heating, cooling, lighting or cooking due to a combination of factors (income cuts, tax increases, rise in unemployment rates, shrinking of welfare benefits, increase in fuel prices, etc.) (Santamouris et al 2013; Πάνας 2012; WWF and Public Issue 2013; Dagoumas & Kitsios 2014) and adopt new individual and collective practices.

This phenomenon, namely the exclusion or the inadequate access of households to energy, which is described as energy poverty and energy deprivation, is at the top of the public debate in Greece and Europe (Healy 2004; Walker & Day 2012; Atanasiu 2014; Santamouris et al 2007). In most cases, however, energy poverty, in the political agenda and the academic discourse, is associated with technical and financial data, such as fuel prices, incomes and the energy efficiency of buildings, without any concern about its geographical aspects which are formed through the production of urban space and especially through the individual and collective practices at different spatial scales (Chatzikonstantinou & Vatavali 2016). In the case of Athens, we argue that the issues of domestic energy consumption and particularly the conflicts and the challenges related with heating can enrich the debate on the impact of the crisis on the socio-spatial relations and inequalities, both at the level of the city and at the level of the apartment building, a type of building which has played a key role in urban development processes in Athens during the postwar era.

Geographies of energy poverty in the Municipality of Athens

The geographical distribution of energy poverty in Athens has been an under-researched topic until today, due to the fact that only recently energy poverty became a significant social problem, to the lack of relevant quantitative data and the difficulties in accessing data at the neighborhood or apartment building level, among other reasons. With this article we intend to create a first macroscopic image of the socio-spatial dimensions of energy poverty, by focusing on the Municipality of Athens. In doing so, we gathered and elaborated primary data about the characteristics and the uses of the buildings, family incomes, energy consumption, as well as about the implemented policies against energy poverty, in order to create a series of thematic maps. The parallel analysis of these thematic maps gives us the chance to draw general and specific conclusions regarding socio-spatial aspects of energy deprivation in Athens during the crisis. This analysis intends to expand the findings of a research project about the emerging geographies of energy poverty in Athens conducted in 2015 through interviews with households that live in apartment buildings in the Municipality of Athens, mapping of quantitative data and policy evaluation [1].

The data that have been used for the production of thematic maps for the Municipality of Athens have been obtained from public institutions and energy providers. The data of the 2011 Census have been analyzed at the Census Tract level, while the data provided by the General Secretariat of Information Systems and the General Secretariat of Public Revenues of the Ministry of Finance, the Hellenic Electricity Distribution Network Operator S.A. and the Electronic Governance of Social Security S.A. have been analyzed at the level of the post code zones. Finally, we should note that our elaborations have been limited by the difficulties and the restrictions in accessing quantitative primary data (protection of personal and commercial data, bureaucracy, problems of communication with the relevant institutions, etc).

Characteristics of the building stock and infrastructure networks

The majority of the buildings in the Municipality of Athens are apartment buildings that have been constructed during the first post-war decades, through the system of antiparohi (i.e. a land-for-flats barter system). Their construction features [2], as well as the fact that only a small part has been adequately maintained since their construction, has led to forming a decaying building stock with serious functional problems – especially concerning energy efficiency. The majority of apartment buildings have a central heating system, without individual choice concerning the amount of heating and the timing. In terms of energy resources, the main parameter is the natural gas network in the neighborhood. Where this network is not available, central heating systems have to use heating oil.

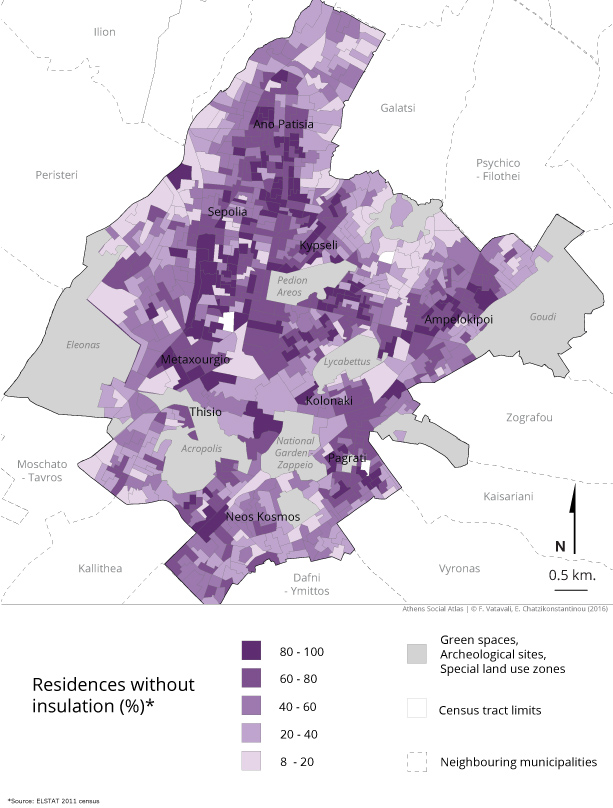

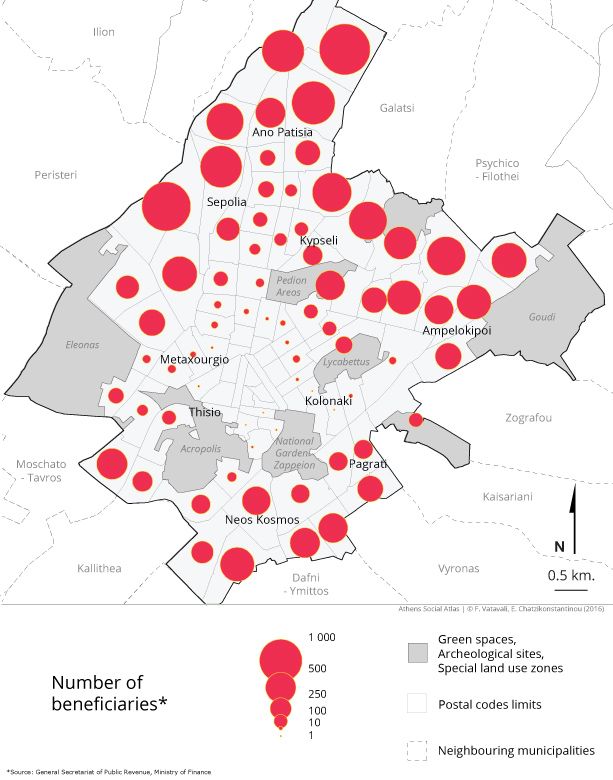

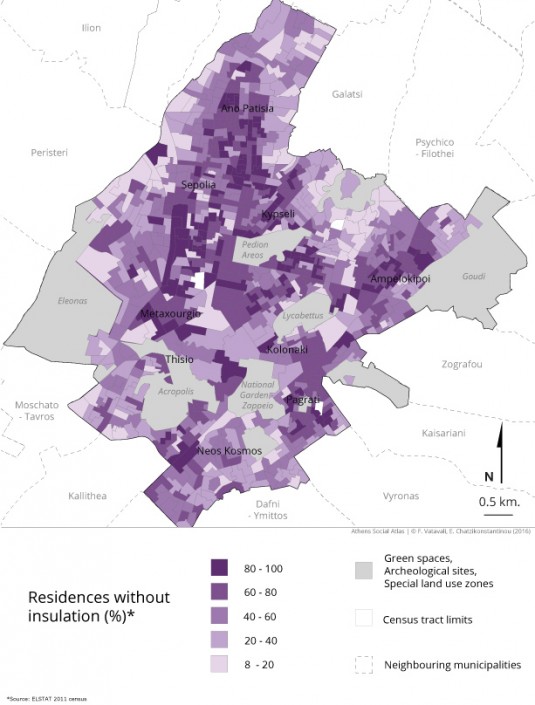

Map 1: Regular dwellings without insulation, 2011

Mapping the Census 2011 data produced by the Greek Statistical Authority (ELSTAT), we see that the percentage of buildings having no insulation at all is rather high all over the Municipality of Athens. In the historical centre, as well as in the districts of Agios Pavlos, Attiki square, Kipseli and Patisia, there are enclaves where more than 80% of dwellings do not have any insulation. In peripheral areas of the Municipality (like Sepolia, Ano Patisia, Ano Kipseli, Poligono) and in small enclaves in the city centre (e.g. the areas around Lycabettus hill) residences lacking insulation are fewer; a fact related to the higher rate of buildings constructed after 1979 –when insulation became obligatory for new buildings (Official Gazette 362D΄/1979).

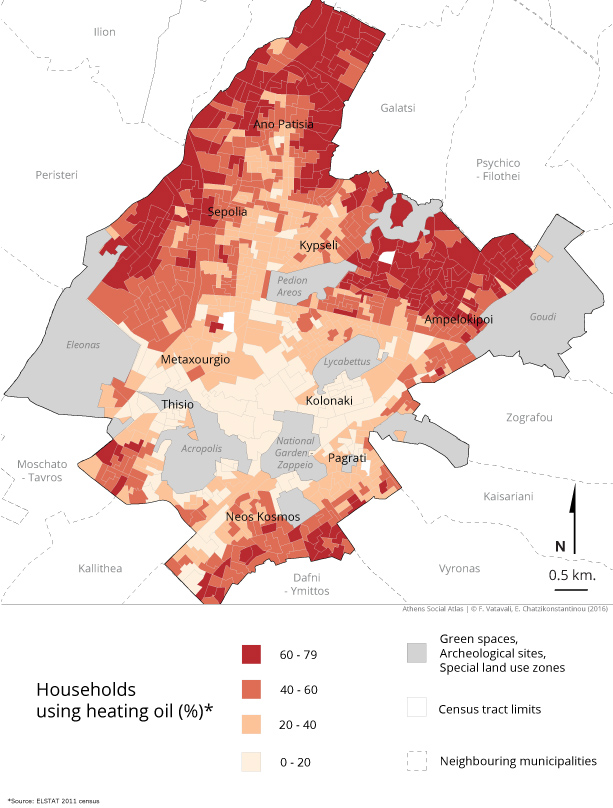

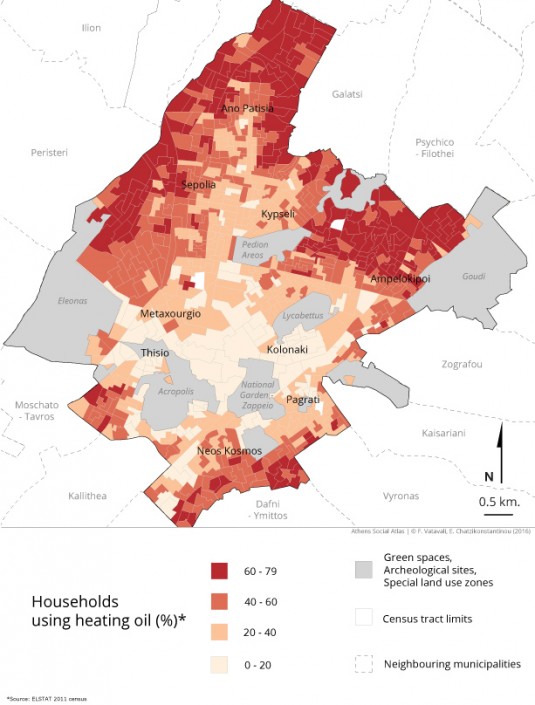

Map 2: Households using heating oil as the main energy resource for heating, 2011

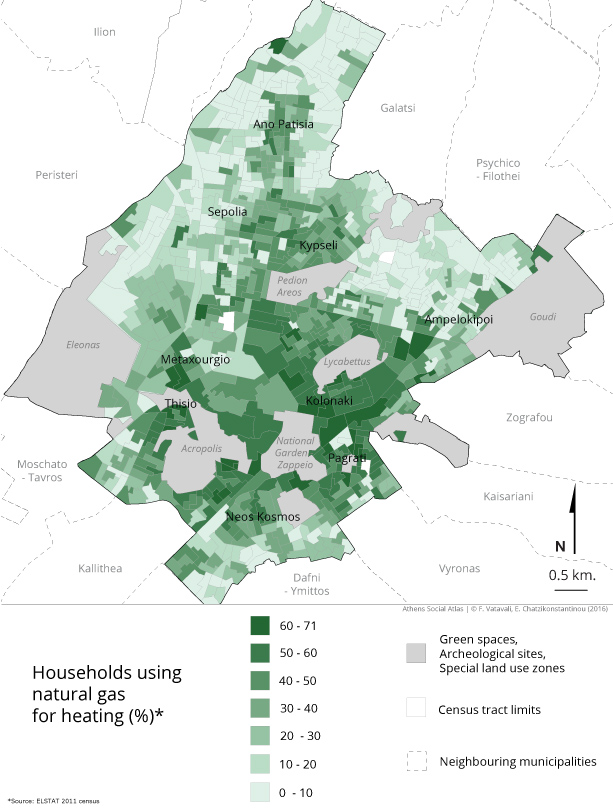

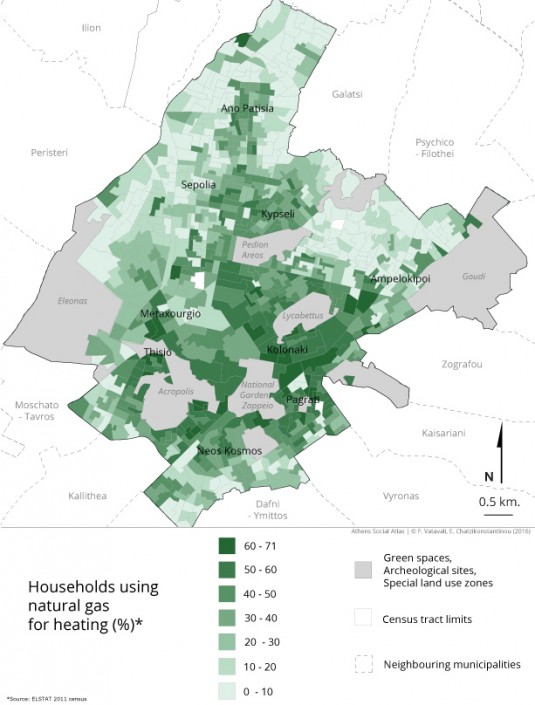

Map 3: Households using natural gas as the main energy resource for heating, 2011

The use of gas oil as the main energy resource for heating is very high in the peripheral neighborhoods of the Municipality of Athens (Ampelokipi, Gkizi, Ano Kipseli, Ano Patisia, Rizoupoli, Promponas, Sepolia, Akadimia Platona, Petralona, Gouva, Neos Kosmoa) and low in central areas (Historical-commercial triangle, Agios Panteleimonas, Kato Patisia, Exarhia, Mousio, Neapoli, Kolonaki, Ilisia, Pagkrati, Koukaki, Thisio, Metaxourgio, Keramikos, Gkazi), while the general picture regarding the use of natural gas as a main resource for heating is exactly the opposite. This is related to the expansion of the natural gas distribution network which covers a big part of the central areas of Athens from the very beginning of the 20th century. Moreover, despite the fact that since 2000 “the use of oil gas for heating water and spaces of residences is forbidden in the historic centre of Athens” (Official Gazette 239B΄/2000) – according to the data of ELSTAT (2011) – the use of oil gas for domestic heating remains high, although it is relatively lower than in other areas of the Municipality of Athens.

Domestic energy consumption

Despite the fact that it is hard – not to mention impossible in some cases – to get access to quantitative data regarding domestic energy consumption in Greece, existing surveys provide an overview of the trends that appeared since the outbreak of the financial crisis. One of the conclusions of these surveys is that energy consumption has been reduced steeply [3] and that households have switched to more affordable fuel sources in order to satisfy their energy needs [4].

As far as Athens is concerned, no official documentation of the problem has been produced, and this is the reason why the overview of the energy poverty issues can only be achieved by combining data from various sources. According to the General Director of Attiki Gas Supply Company (EPA ATTIKIS), households living in about 33% of the apartment buildings in Athens in winter 2012-2013 and in about 44% in winter 2013-2014, did not use the central heating system [5]. Moreover, according to data of the Hellenic Electricity Distribution Network Operator S.A. (HEDNO), the electric power consumption in the Municipality of Athens was reduced by 12% per residence from 2008 to 2015. Also, the consumption of oil gas in the Metropolitan Area of Athens was reduced from 920,664tn in 2008 to 271,792tn in 2013, namely by 70.5% (ELSTAT 2016b). Apart from the shrinkage of income and the international rise in fuel prices, this reduction is directly related to the implemented policies and especially to the rise in the taxes on oil gas, which was imposed aiming at the reduction of the black market in fuel and the increase of state revenues.

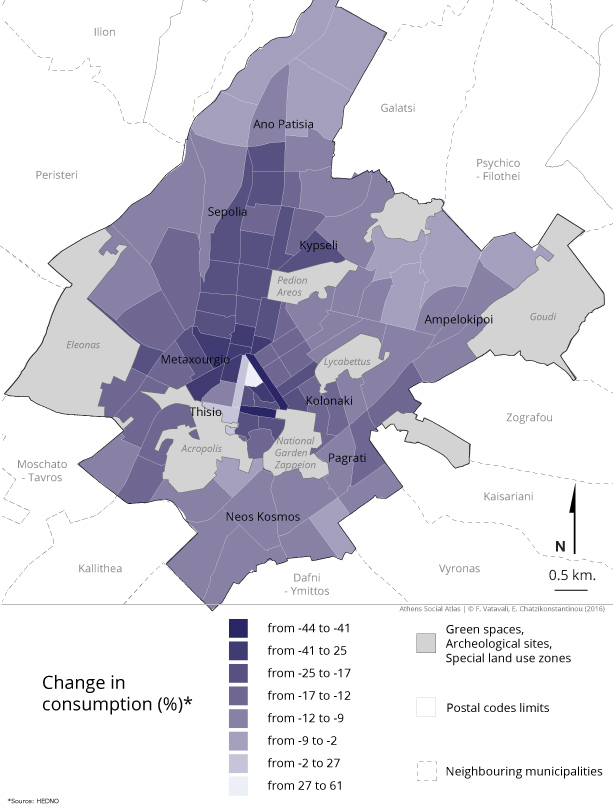

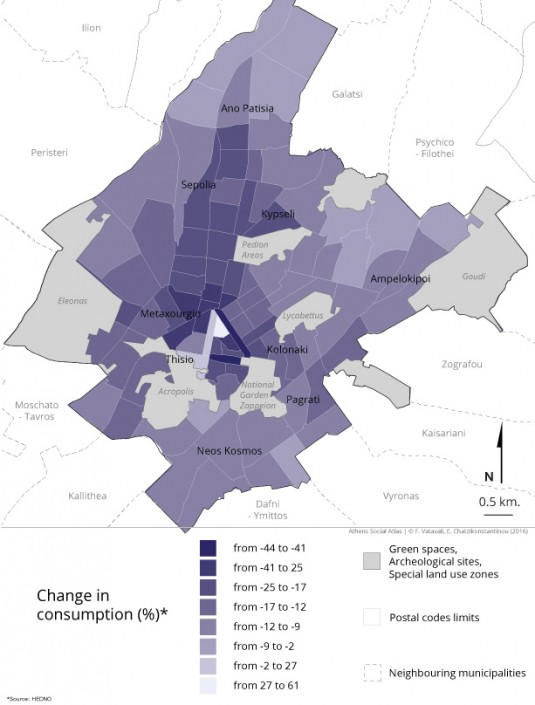

Map 4: Change in domestic electricity consumption, 2008-2015

From 2008 to 2015, electric power consumption has been reduced all over the Municipality of Athens, except from some small enclaves in the central areas, where it has slightly increased. The extent of reduction varies greatly. In particular, in some central areas (Omonia, Vathis square, Metaxourgio, Psirri, Gerani) reductions are rather high, varying from 25% to 40% per consumer. High reductions in electric power consumption are spotted also in areas between Patission Avenue and the metro-line 1, as well as in the areas of Mousio, Plaka and Kolonaki. The reduction of electricity consumption is lower in the northern parts of the Municipality (Ano Patisia, Rizoupoli, Prompona), as well as in the areas of Poligono, Girokomio and Ampelokipi.

Policies for tackling energy poverty

Considering the significant increase of energy deprivation, a wide range of policies and urgent measures have been implemented since 2012 in order to meet the energy needs of specific social and income groups: subsidies for heating oil, social tariff for domestic electricity consumers, electricity reconnections for indebted households which were previously cut off, free access to electricity for extremely poor households, favourable arrangements for debts and arrears on electricity bills, low electricity prices on days when weather conditions favour the creation of smog, as well as discounts for electricity consumers who pay on time. The relevant maps depict, on the one hand, the spatial dimensions of energy poverty and of poverty in general in Athens and, on the other hand, the spatiality of policies and measures against energy poverty.

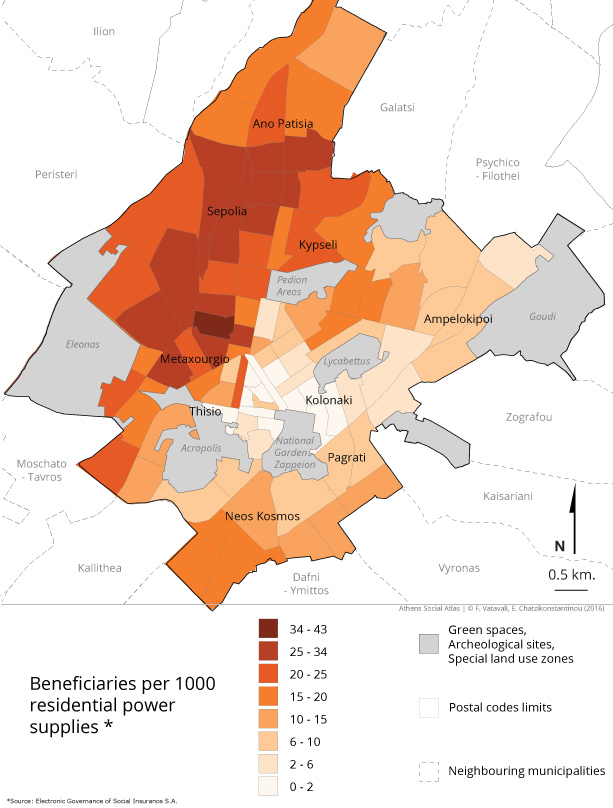

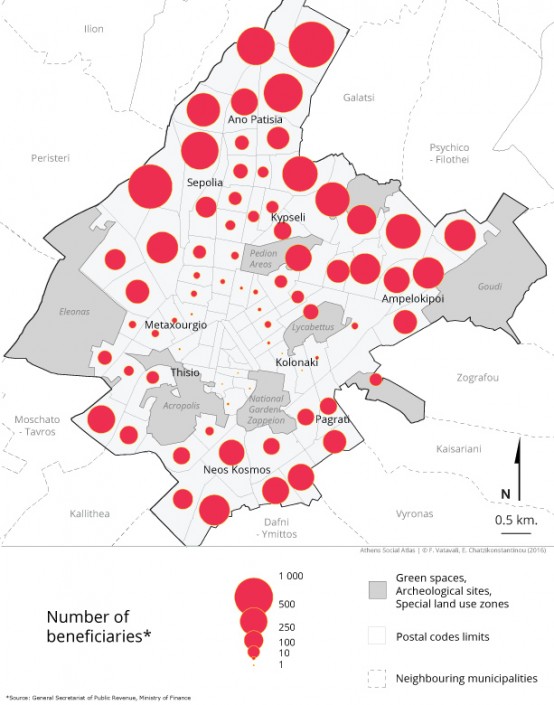

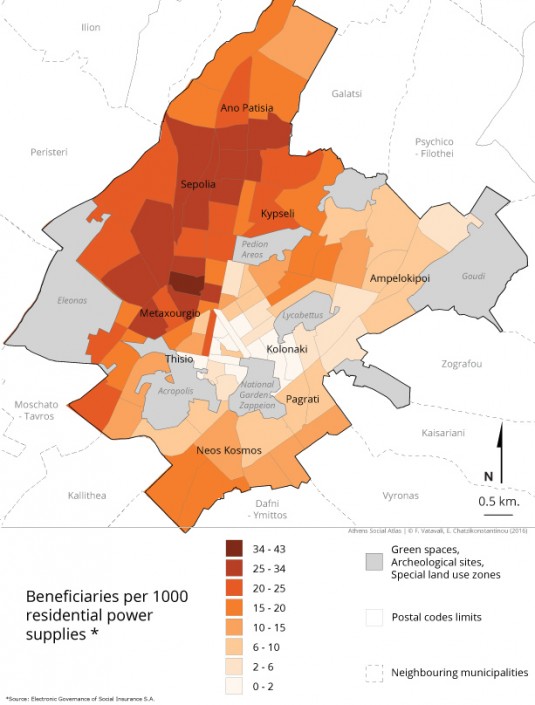

Map 5: Beneficiaries for the heating oil subsidy, 2014

In order to help households in their effort to satisfy their heating needs, the Ministry of Finance implemented a series of heating oil subsidy programs from 2012-2013 to 2015-2016 (Government Gazette 3049B΄/2012, 2656B΄/2013, 2820B΄/2014, 2677B΄/2015). At the national level, the number of beneficiaries was 184,973 for 2013-2014 and reached 351,043 in 2014-2015 (Ministry of Finance 2014), while, according to the data of the General Secretariat of Public Revenues, in the Municipality of Athens there were 12,057 beneficiaries in 2013, 21,935 in 2014 and 23,012 in 2015.

The mapping of the statistical data of the Secretariat General of the Public Revenues reveals that during 2012-2015 the concentration of the beneficiaries for the oil subsidy was higher in the peripheral areas of the Municipality of Athens. In 2014, for example, there was high concentration of beneficiaries for this subsidy in the areas of Sepolia, Rizoupoli, Ano Patisia, Ano Kipseli, Poligono, Girokomio and Neos Kosmos. This is related to the high concentration of buildings in which oil is used for central heating and consequently of households that are possibly entitled to receive subsidy for heating oil. It also reflects the income and property value criteria for eligibility posed by the programs, which were quite broad and, apart from the very low-income groups, included broader lower middle-income groups [6] .

Moreover, it is noteworthy that in areas with low-income households, there are less beneficiaries than expected, due to the high concentration of immigrants’ households which are excluded either because they lack the necessary legal documents or they do not have access to the relevant information. In this sense, Map 5 does not represent accurately the spatial distribution of energy poverty, because the information it conveys is a combination of parameters that are not necessarily related to all the types of obstacles in accessing energy.

.

Map 6: Beneficiaries of the Program for Confronting the Humanitarian Crisis for free electricity and reconnection to electricity network, 2015

In 2015, the Ministry of Labor, Social Security and Social Solidarity announced a program for supporting the households living in extreme poverty which offers to the beneficiaries access to food and housing, as well as 300 kWh of free electricity consumption per month, free reconnection to the electricity network and favourable arrangements for households who have been disconnected from the electricity network due to debts (Governmental Gazette 29A΄/2015 and 577B΄/2015). 89,288 families with 212,216 members had access to these subsidies at the national level and the implementation of this measure was extended to 2016. In particular, according to the data of the Electronic Governance of Social Security S.A., there were 7,849 beneficiaries for the free reconnection and access to electricity in 2015 in the Municipality of Athens.

According to the data of the Electronic Governance of Social Security S.A., there is a high concentration of beneficiaries for the subsidy for access to electric power in the areas of Sepolia, Kipseli, Patisia, Kolonos, Akadimia Platona, Agios Pavlos and Metaxourgio, while concentration is very low in central areas, such as Thision, Plaka and Kolonaki. The spatial distribution of the beneficiaries of the electricity subsidy reflect to a great extent the concentration of poverty in Athens, as, on the one hand, electricity is a basic amenity for all households, and on the other hand the financial criteria posed by the program exclude middle-income groups. However, considering that income is the only criterion for applying for electricity subsidy, the spatial distribution of beneficiaries does not provide a fully reliable input about the spatial patterns of energy deprivation.

Conclusions

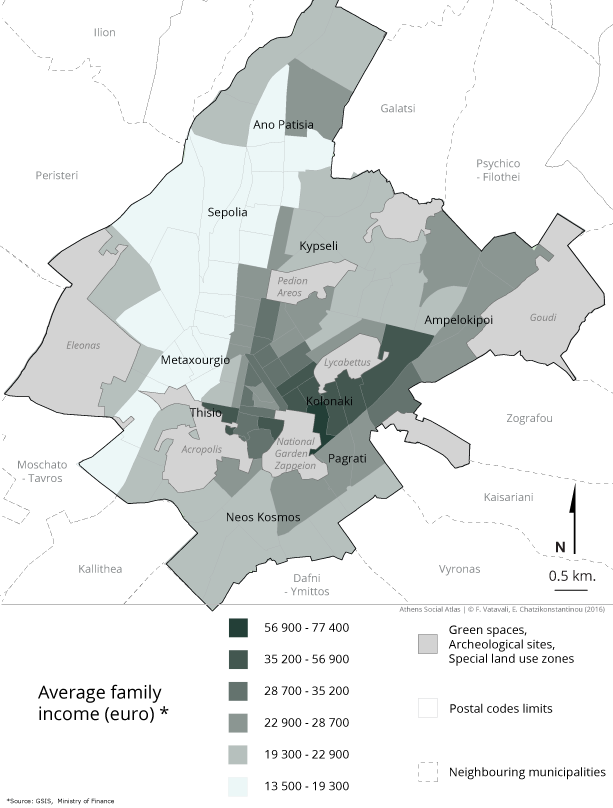

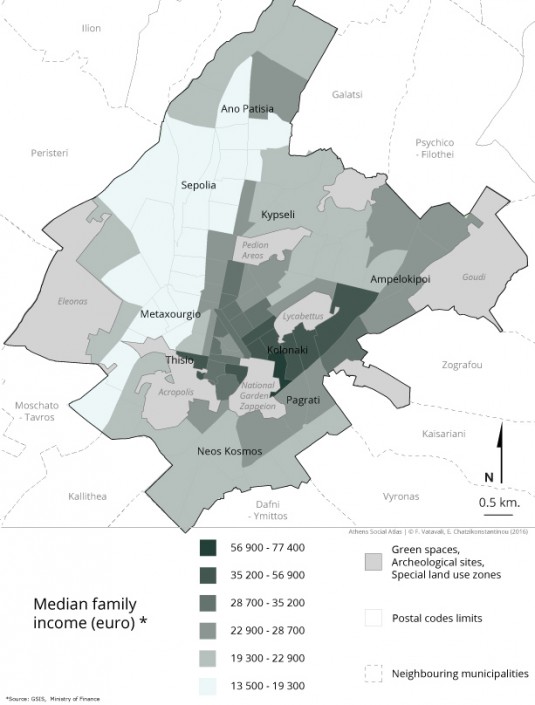

According to the thematic maps presented here, there is no clear segregation among the neighbourhoods of the Municipality of Athens, as devaluation and low energy efficiency of the building stock, poverty as well as reduction in energy consumption are widespread. This finding complements the academic discourse about social mixture in Athens during the post-war period (Mantouvalou 1996; Mantouvalou & Mavridou 1993; Maloutas et al 2006). However, there are areas in the Municipality of Athens where living conditions are deteriorating and problems are acute. The area with the most severe problems is the zone that includes part of the historic centre of Athens and the neighbourhoods to its north (Patisia, Sepolia, Kipseli, etc). In this zone, the concentration of low income groups (see Map 7 for the spatial distribution of income groups) and devaluated buildings is very high, the reduction in energy consumption is also high, while the possibility of access to cheaper energy through the natural gas network does not seem to play a crucial role.

Map 7: Average family income, economic year 2011

This situation corroborates the findings of other research projects conducted in Greece or abroad, that stress the importance of the relation between low income and energy poverty. But still, the broader picture is more complex. In neighbourhoods with severe problems there are spatial enclaves of a relatively better condition, whereas enclaves of poverty, devaluation of living standards and energy deprivation are not uncommon in more privileged areas; this finding is also confirmed by qualitative research (Chatzikonstantinou & Vatavali 2016).

As far as the programs for tackling energy poverty are concerned, our findings show that the number of beneficiaries is limited compared to needs, and is not particularly concentrated in the areas with the biggest problems. The only exception is the program of the Ministry of Labor, Social Security and Social Solidarity providing free access to electricity for vulnerable groups, the beneficiaries of which are concentrated in low income neighbourhoods. But even in this case, the inability of households to satisfy their energy needs is mainly dealt with by income support, and not by a long-term strategy for addressing energy deprivation. Moreover, the benefits are the same for all beneficiaries, without any graduation according to households’ resources, buildings’ characteristics, and in fact without an accurate account of the spatial distribution of energy poverty.

All in all, we could say that the discourse about domestic energy consumption and the insights emerging from the thematic maps are interconnected with the wider assumption about the creation of multiple speeds and new polarizations in the neighbourhoods of Athens in the context of the Greek debt crisis (e.g. Encounter Athens 2011; Maloutas et al 2013). In this sense, the question that arises regarding the distribution of energy poverty in the urban space is whether the growing gap in the living standards among the neighbourhoods of the city and more generally the widening of social inequalities could transform the everyday life of the inhabitants of Athens, as well as the processes of space production and social integration in the city.

[1] The research project titled “Geographies of energy poverty in Athens in the crisis” was funded in 2015 by the John S. Latsis Public Benefit Foundation.

[2] According to the 2011 Census, 80% of the regular residences in the Municipality of Athens have been constructed before 1980. See also: Maloutas & Spyrellis 2015.

[3] According to a survey by WWF and Public Issue (2013) 81% of the households surveyed have reduced their expenditure on heating and cooling, while 74% reduced their electricity consumption. A similar picture is described by a survey conducted in the Northern Greece by the Department of Statistics of Athens University of Economics and Business, according to which 62.4% of households spend more than 10% of their total income on heating, 78.6% use less heating than they need because they cannot afford it and 64% declared they are unable to pay their heating bills (Panas 2012). Furthermore, a survey conducted by Santamouris et al (2013) concluded that between winter 2010/2011 and winter 2011/2012 domestic energy consumption dropped by 15%, despite the fact that the second winter was colder, and the ratio of fuel-poor households increased from 11.1% to 11.7%. Finally, according to data from the Family Budgets surveys of the Hellenic Statistical Authority, the percentage of households using central heating has fallen from 76% in 2008 to 35.5% in 2014 (ELSTAT 2016a), a percentage reduction of 46.7%. More precisely, the annual percentage reduction of households using central heating from 2008-2009 to 2013-2014 was 2.5%, 0.4%, 1%, 22.6% and 2.6% respectively (ELSTAT 2010, 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2015).

[4] In order to satisfy their heating needs in 2010, 65.9% of households were mainly heated by oil-burning systems, 7.2% by natural gas, 11.8% by stoves, 4.7% by electrical appliances, 4.8% by air-conditioning and 4.9% by other heating means. In 2014, the percentage of households that were mainly heated by oil-burning systems dropped to 35.5%, while 9.2% were heated by natural gas, 15.8% by stoves, 13.5% by electrical appliances, 12.8% by air-conditioning and 11.4% by other heating means. It is worth noting that 0.5% of households in 2010 and 1.8% in 2014 declared that they had no heating at all (ELSTAT 2016).

[5] Kathimerini (2014), “Without central heating 4 out of 10 apartment buildings in Athens,” 12/2/2014.

[6] In 2012, the beneficiaries should have annual family income less than 35,000 euro and nominal value of landed property less than 200,000 euro, in 2013 and 2014 the annual family income should not exceed 40,000 euro and the nominal value of landed property should be less than 300,000 euro, while in 2015 potential beneficiaries were reduced with maximum annual family income at less than 20,000 euro and nominal value of landed property at less than 200,000 euro.

Entry citation

Chatzikonstantinou, E., Vatavali, F. (2016) Mapping energy poverty in Athens during the crisis, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/energy-poverty/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.67

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Encounter Athens (2011) Ποια «κρίση» στο κέντρο της Αθήνας. Κριτικός λόγος και διεκδικήσεις για μια δίκαιη πόλη. Available from: https://encounterathens.wordpress.com/page/11/ (accessed 21 July 2016).

- WWF Hellas – Public Issue (2013) Έρευνα για το πρόγραμμα «Καλύτερη ζωή», Διαγραμματική παρουσίαση της έρευνας. Αθήνα. Available from: http://www.wwf.gr/images/pdfs/publicIssue-graphs-better-life.pdf.

- ΕΛΣΤΑΤ (2015) Έρευνα Οικογενειακών Προϋπολογισμών 2014. ΕΛΣΤΑΤ. Available from: http://www.statistics.gr/el/home?p_p_id=3&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=maximized&p_p_mode=view&_3_struts_action=/search/search&_3_redirect=/el/home/&_3_keywords=Έρευνα+Οικογενε%25C.

- ΕΛΣΤΑΤ (2012) Έρευνα Οικογενειακών Προϋπολογισμών 2009. ΕΛΣΤΑΤ. Available from: http://www.statistics.gr/el/home?p_p_id=3&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=maximized&p_p_mode=view&_3_struts_action=/search/search&_3_redirect=/el/home/&_3_keywords=Έρευνα+Οικογενε%25C.

- ΕΛΣΤΑΤ (2014) Έρευνα Οικογενειακών Προϋπολογισμών 2013. ΕΛΣΤΑΤ. Available from: http://www.statistics.gr/el/home?p_p_id=3&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=maximized&p_p_mode=view&_3_struts_action=/search/search&_3_redirect=/el/home/&_3_keywords=Έρευνα+Οικογενε%25C.

- ΕΛΣΤΑΤ (2010) Έρευνα Οικογενειακών Προϋπολογισμών 2008. ΕΛΣΤΑΤ. Available from: http://www.statistics.gr/el/home?p_p_id=3&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=maximized&p_p_mode=view&_3_struts_action=/search/search&_3_redirect=/el/home/&_3_keywords=Έρευνα+Οικογενε%25C.

- ΕΛΣΤΑΤ (2015) Συνθήκες διαβίωσης στην Ελλάδα. ΕΛΣΤΑΤ. Available from: http://www.statistics.gr/living-conditions-in-greece.

- ΕΛΣΤΑΤ (2012) Έρευνα Οικογενειακών Προϋπολογισμών 2010. ΕΛΣΤΑΤ. Available from: http://www.statistics.gr/el/home?p_p_id=3&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=maximized&p_p_mode=view&_3_struts_action=/search/search&_3_redirect=/el/home/&_3_keywords=Έρευνα+Οικογενε%25C.

- Μαλούτας Θ, Εμμανουήλ Δ και Παντελίδου Μαλούτα Μ (2006) Αθήνα. Κοινωνικές δομές, πρακτικές και αντιλήψεις: Νέες παράμετροι και τάσεις μεταβολής 1980-2000. Αθήνα. Available from: http://www.ekke.gr/open_books/athens_2006.pdf.

- Μαλούτας Θ και Σπυρέλλης ΣΝ (2016) Η πολυκατοικία της αντιπαροχής και ο κάθετος κοινωνικός διαχωρισμός. Κοινωνικός Άτλαντας της Αθήνας. Available from: http://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/άρθρο/κάθετος-διαχωρισμός/ (ημερομηνία πρόσβασης 4 Σεπτέμβριος 2016).

- Μαντουβάλου Μ (1996) Αστική γαιοπρόσοδος, τιμές γης και διαδικασίες ανάπτυξης του αστικού χώρου ΙΙ: προβληματική για την ανάλυση του χώρου στην Ελλάδα. Επιθεώρηση Κοινωνικών Ερευνών 89–90: 53–80. Available from: http://ejournals.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/ekke/article/view/7276/6996.

- Μαντουβάλου Μ και Μαυρίδου Μ (1993) Αυθαίρετη δόμηση: μονόδρομος σε αδιέξοδο. Δελτίο Συλλόγου Αρχιτεκτόνων, Αθήνα 7: 58–71.

- Πανάς Ε (2012) Έρευνα για την ενεργειακή φτώχεια στην Ελλάδα. Αθήνα. Available from: http://library.tee.gr/digital/m2600/m2600_panas.pdf.

- Συλλογικό Έργο (2013) Το κέντρο της Αθήνας ως πολιτικό διακύβευμα. Μαλούτας Θ, Κανδύλης Γ, Πέτρου Μ, κ.ά. (επιμ.), Αθήνα: ΕΚΚΕ, Χαροκόπειο Πανεπιστήμιο.

- Atanasiu B, Kontonasiou E and Mariottini F (2014) Alleviating fuel poverty in the EU: investing in home renovation, a sustainable and inclusive solution. BPIE (Buildings Performance Institute Europe), Brussels. Available from: http://bpie.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Alleviating-fuel-poverty.pdf.

- Chatzikonstantinou E and Vatavali F (2016) Energy Deprivation and the Spatial Transformation of Athens in the Context of the Crisis: Challenges and Conflicts in Apartment Buildings. In: Großmann K, Schaffrin A, and Smigiel C (eds), Energie und soziale Ungleichheit, Berlin: Springer, pp. 185–207.

- Dagoumas A and Kitsios F (2014) Assessing the impact of the economic crisis on energy poverty in Greece. Sustainable Cities and Society, Elsevier 13: 267–278.

- Healy JD (2004) Housing, fuel poverty, and health: a pan-European analysis. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Santamouris M, Kapsis K, Korres D, et al. (2007) On the relation between the energy and social characteristics of the residential sector. Energy and Buildings, Elsevier 39(8): 893–905.

- Santamouris M, Paravantis JA, Founda D, et al. (2013) Financial crisis and energy consumption: a household survey in Greece. Energy and Buildings, Elsevier 65: 477–487.

- Sardianou E (2008) Estimating space heating determinants: An analysis of Greek households. Energy and Buildings, Elsevier 40(6): 1084–1093.

- Walker G and Day R (2012) Fuel poverty as injustice: Integrating distribution, recognition and procedure in the struggle for affordable warmth. Energy policy, Elsevier 49: 69–75.