Pedestrianization in the centre of Athens: A brief history and some questions

Kanellopoulou Dimitra

Built Environment, Infrastructures, Planning, Transports

2016 | Dec

Introduction

This article is based on research carried out as part of my doctoral dissertation whose subject was walking and pedestrianization in the centre of Athens (Kanellopoulou, 2015). My objective, in this text, is to show the historical development of pedestrianization policies and the main (government) bodies responsible for the design of public spaces in the Greek capital. Although soft mobility in Athens is a marginal topic compared to other European cities (ESPON/TEMS), numerous public works on both a minor and major scale have taken place from 1970 to the present. These works dramatically changed the quality of the urban environment as well as the way in which this environment was perceived by pedestrians on their daily routes. Despite the initial objective of the local authority and of central government to create an entire network of pedestrian zones as well as to connect all archaeological sites, already in the 60s (Ζήβας, 2003), public works only progressed to a certain level. The fragmented nature of pedestrianization in the neighbourhoods of the seven districts of the Municipality of Athens and the beautification of roads of metropolitan significance, have raised questions regarding the geographical location of streets which became pedestrian, but also regarding urban planning and its symbolic role in the configuration and utilization of public space in the city.

This article is based on the collection of data from primary as well as secondary sources. Primary sources refer to forty interviews, which were carried out between 2011 and 2014 with public and private sector organizations in Athens, as well as various unpublished maps of that era which were given to me during the interviews. The secondary sources are technical texts and articles of that era and can be accessed by the reader in the archives of the local authority as well as in the archives of the organizations referred to in this article. The maps were personally revised by Stavros Nikiforos Spyrellis based on my thesis’ data.

The vision for a pedestrianized historical centre (1970-1990)

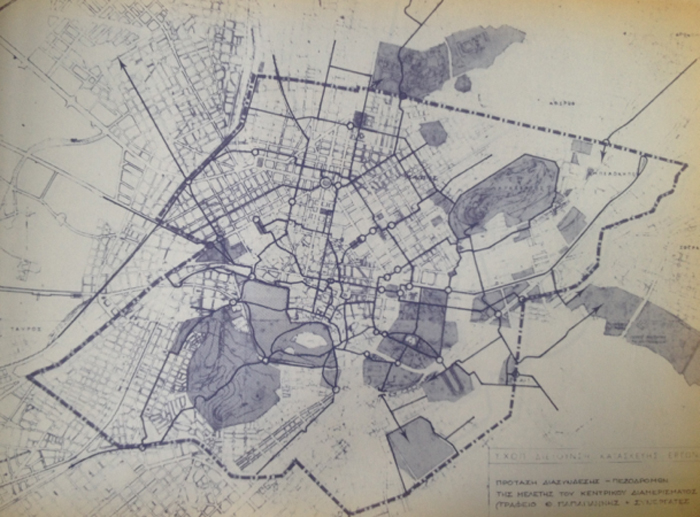

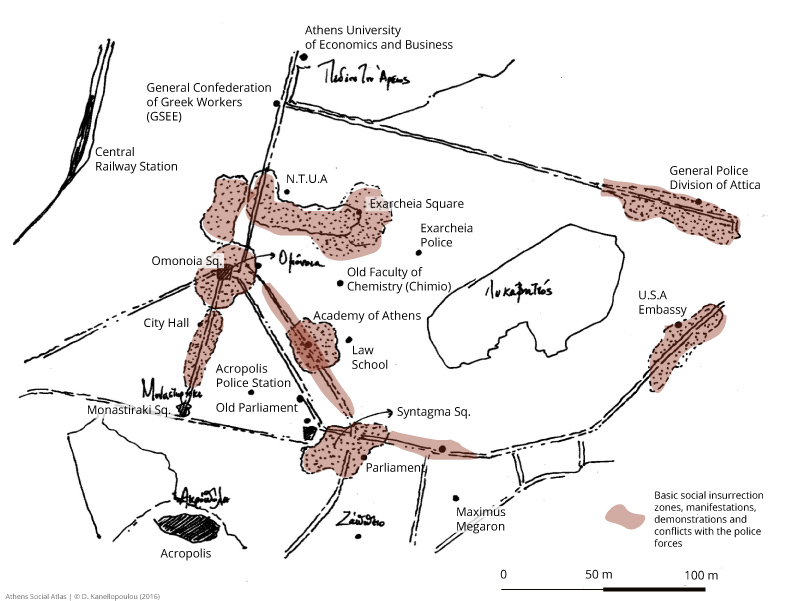

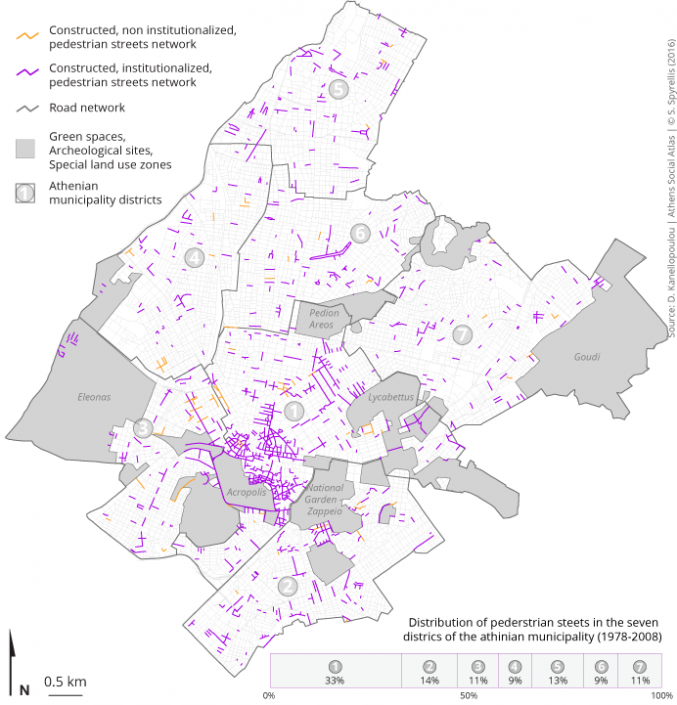

When the Ministry of Public Works (YΔΕ) began digging up Voukourestiou Street in the 1970s, thereby profoundly changing the landscape on this bustling road by transforming it into a big pedestrian street, a large section of the media, shop owners and even politicians reacted by saying the project was a result of a beautification intervention which would not be able to solve the problems nor meet the needs of the city (Μάνος, 2013). On the cover of The Architects’ Association Bulletin in 1978 (Figure 1), there is a comic by a well-known cartoonist (KYR) showing a newspaper agent in the middle of a flooded Voukourestiou Street shouting “Newspapers….Voukourestiou Street pedestrianiiiiized”. In the late 70s and early 1980s Athens experienced dramatic floods, so the projects to restore public space seemed to be, for most Athenians, a luxury. Discussions regarding quality of life improvements were considered “empty words” or just figments of the imagination of urban planners ( Μάνος, 2013). In this climate of mistrust, a group of architects, urban planners and designers from the Ministry of Regional and Urban Planning and the Environment (Υ.Χ.Ο.Π.) began compiling studies regarding the connection of green spaces with significant monuments in the centre of Athens via upgraded pedestrian routes (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Cover of the Bulletin of the Greek Architects Association (1978) where the cartoonist KYR relates the announcement of pedestrianization projects with the extensive floods experienced by the city at that time

Source: A. Geronikou archive – Technical Department of the Municipality of Athens

Figure 2: Interconnection of pedestrian streets in the central District of the Municipality of Athens

Source: Study of the central District of the Municipality of Athens by Th. Papagiannis & Associates for the Ministry of Planning and the Environment. S. Koulis archive

This group was accountable to ‘The Special Service for Public Works [1] for the Upgrading of Free Public Spaces and Area Renewal’ (ΕΥΔΕ – ΑΕΚΧΑΠ) and comprised employees of the Ministry and external experts, who were supported by the Minister Stefanos Manos. They lay the foundations for a vast plan which would reveal the historical nature of the centre of Athens and reclaim parts of public space for pedestrians [2]. The pedestrianization of Voukourestiou Street was not without precedent however, as the plan to restore the historical neighbourhood of Plaka had already been implemented. Apart from numerous architectural interventions on buildings, this plan also included the construction of an extended network of pedestrian streets (Figure 3) within that traditional neighbourhood (Μιχαήλ, 1986)

Figure 3: Proposed pedestrianization (in light green colour) in the neighbourhood of Plaka

Source: Leaflet of the Ministry of Planning and the Environment (1980). N. Remoundou-Triantafylli archive

The role of the Technical Department of the Local Authority and the State

In the early 1980s, the vision of a pedestrianized centre in Athens became a plan and gradually became a reality due to parallel, even though perhaps not co-ordinated actions on the part of the Ministry and of the Technical Department of the Municipality of Athens. It is important to stress that urban planning policies regarding the restoration and pedestrianization of public spaces were radically modified due to the recruitment by the Ministry of a new, younger generation of architects (Τουρή, 2013) as well as to the alignment of objectives and policies amongst local and central authorities. The Ministry’s plan to restore the city centre aimed at creating a network of pedestrian streets which would connect historical squares, significant monuments and archaeological sites (Κουλής, 2014) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Network of pedestrian flows determined by the Ministry of Planning and the Environment for the centre of Athens

Source: Γιαννόπουλος (1980)

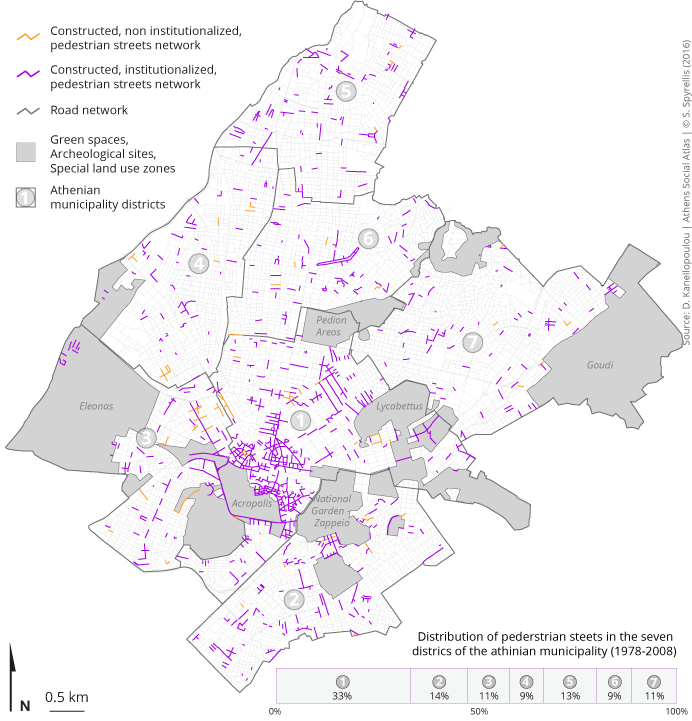

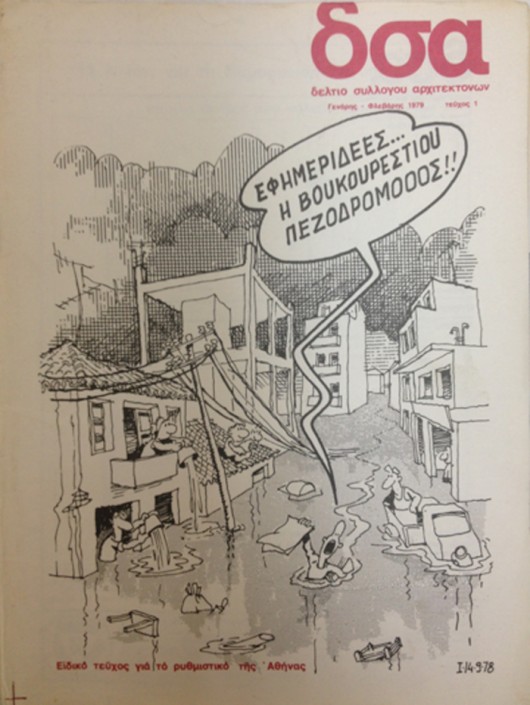

The Municipality’s Department of Urban Planning along with the Department of Architecture and the Department of Public Works constructed numerous pedestrian streets on a small scale in neighbourhoods in all seven Districts of Athens (known as District Units today) (Map 1, Graph 1&2)

Map 1: Pedestrian streets in the Municipality of Athens

Graph 1: Pedestrianization in the Municipality of Athens (1972-2008)

Graph 2: Pedestrianization in the the 1st, 2nd and 5th District of the Municipality of Athens (1972-2008)

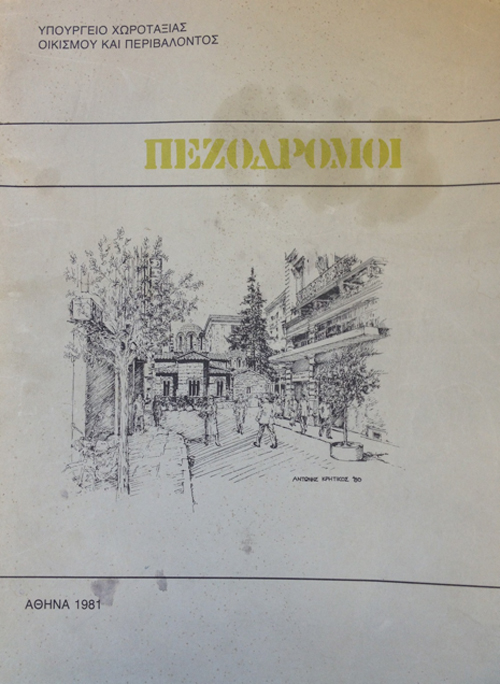

The researchers within the ΕΥΔΕ- ΑΕΚΧΑΠ group experimented both in design and construction by trying out materials and discussing the project with both developers and contractors regarding the different possibilities in construction (Figure 5). The employees of the Technical Department were able to gain know-how concerning land use, based on observation, trial and adjustment to the Athenian landscape on a daily basis. The Municipality, in co-operation with the Ministry (ΥΧΟΠ), completed numerous pedestrianization projects on a small scale in densely populated neighbourhoods in the city centre, particularly in areas around school buildings, churches and small open spaces at road junctions (Σκιαδά, 2013) (Figure 6).

Figure 5: Pavement cover at Aiolou pedestrian street

Source: Κανελλοπούλου (2014)

Figure 6: Cover of Booklet on the Design of Pedestrian Streets published by the Ministry of Planning and the Environment

Source: Archive of the Municipality of Athens Master Plan

An instrument of Urban Planning in Athenian neighbourhoods

Until the 1990s the case of Plaka remained the only completed plan of an extensively pedestrianized district. Pedestrianization was fragmented for the most part and often the construction of pedestrianized thoroughfares preceded its validation from the Municipal Council of the Local Authority as well as its legalisation by the Ministry through the required modification in the city’s Master Plan (Figure 7) (Kanellopoulou, 2015).

Figure 7: Detail of circular on the design representing pedestrian ways in Master Plans

Source: Archive of the Master Plan of the Municipality of Athens

Apart from providing pedestrian zones to improve daily living in densely populated urban areas, pedestrianization also took on a new symbolic meaning. It became a very successful instrument in the hands of political authorities who found in it an inexpensive means (i.e. not requiring the expropriation of private property) that had immediately visible results for the local community (Τουρή, 2013). As far as the Municipality was concerned, most of the pedestrianization projects were implemented following requests from one or more residents (Παπακωνσταντίνου, 2012). The Municipality’s engineers, who were responsible for these projects, after checking the impact of eliminating traffic from the area that was to become pedestrian and on the broad district as a whole, made recommendations to the Municipal Council for the final transformation of the road into a pedestrian street. Despite their fragmented nature (Map 2) the numerous pedestrian zones produced by the Municipality, visibly changed the feeling at the micro-scale and the attractiveness of the affected streets in Athenian neighbourhoods (Τσιώρα, 1998). They also familiarized Athenians with the concepts of public space free of cars, leisure time, urban green space and pedestrian zone (Ρεμούνδου, Πανέτσος, 1994).

Map 2: The development of pedestrian ways network in the Municipality of Athens (1978-2008)

The Olympic Games of 2004 as a goal since 1990

Following an especially productive decade of pedestrianization projects on the small scale, the early 1990s heralded an era in new urban planning policies and priorities both for the Municipality and the Ministry. The Company for the Unification of Archaeological Sites in Athens (ΕΑΧΑ) (ΦΕΚ 909/B/1997), was created in 1990 and marked the decision of the Ministry to intervene drastically and on the large scale in public space at the city centre. This new agency was responsible for devising and applying the plan to unify the city’s archaeological sites in an uninterrupted walk (Figure 8).

Figure 8: The six zones of intervention in the centre of Athens

Source: Announcement by the Ministry of Environment, Planning and Public Works and the Ministry of Culture (Archive of the Master Plan of the Municipality of Athens)

As Athens gradually became a European capital competitive as a tourist destination after the mid 1990s (Fola, 2011), the restoration of the centre of Athens was perceived as a challenge which would allow a section of the political and media elites to form a coalition around the concept of an essential “face lift” (Κεχαγιά, 2011, Ζιαμπάκας, 2015) of the city’s public space. EAXA started pursuing its target to complete 145 architectural interventions in ten years [3]. EAXA consolidated its role as an agency which designs public spaces, and its reputation was built upon the completion of a particular project thought to be a milestone for Athens. Dionysiou Areopagitou Street, i.e. the road at the foot of the Acropolis hill, was transformed into a two kilometre long pedestrian street in 2001 (Καλαντίδης, 1998). This pedestrian street (Figure 9) connects Thisio rail station with Makriyanni Street and the Pillars of Olympian Zeus. Pedestrianization took on symbolic significance because it signalled the beginning of an era of research and projects of metropolitan range and significance. These projects developed features which affected the aesthetics of space as well as the procurement and construction procedure of the works [4]. As a result, new administrative bodies and new procedures producing public space were initiated, reshuffling radically the way relevant procedures were performed until 1990, when everything lay completely in the hands of the Municipality and the central government.

Figure 9: Plan of the pedestrianization at the junction of Makryianni and Dionysiou Areopagitou streets completed in 2003

Source: Archive of the Company for the Unification of Archaeological Sites in Athens (Ε.Α.Χ.Α. SA)

From the pedestrian zone …to a soft mobility zone

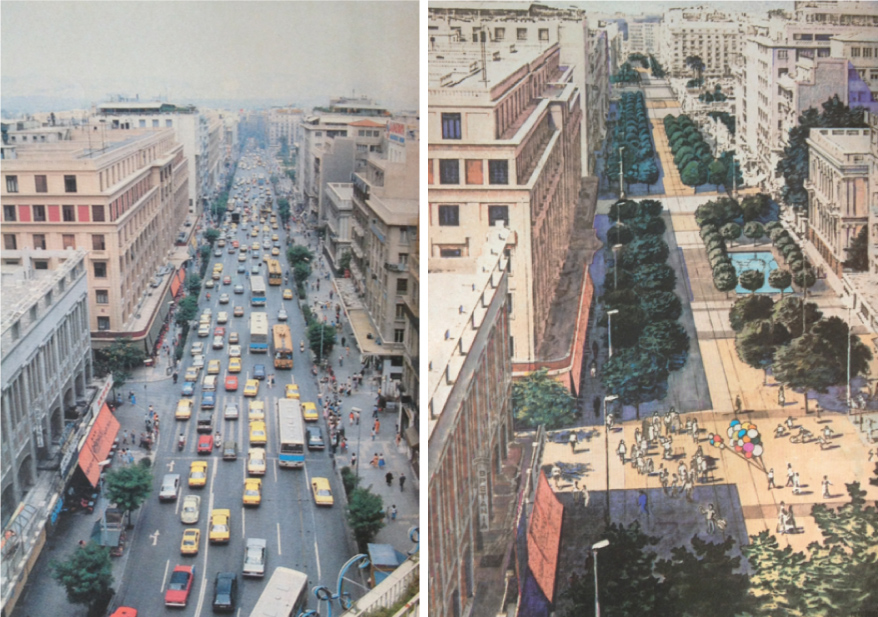

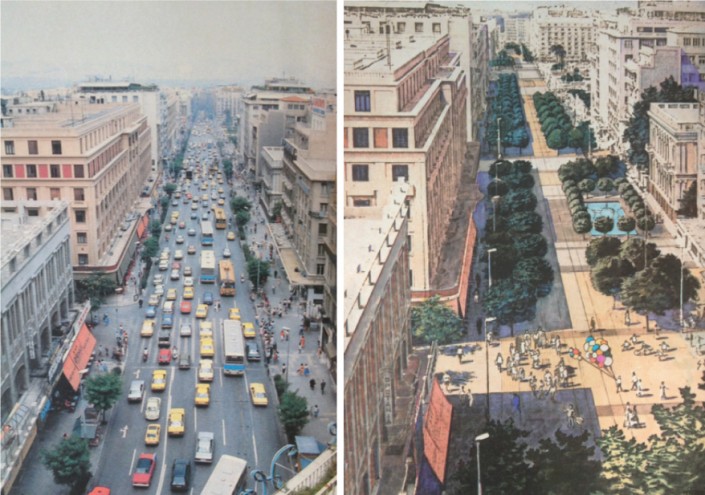

Ten years after the completion of Dionysiou Areopagitou Street, the idea for another large scale pedestrian street came to the forefront with the announcement of the Rethink Athens [5] tender. In the midst of the economic recession and generally amid many social problems in the centre of Athens [6], the focus of the Ministry of the Environment and Energy (ΥΠΕΚΑ) in an ambitious restoration project on Panepistimiou Street (Τζαναβάρα, 2011), indicated the central government’s conscious choice to promote spatial interventions in the city as a major response to the economic and image crisis that Athens was facing (Kanellopoulou, 2015). The idea of pedestrianizing Panepistimiou Street first appeared in 1983 as a proposal to the Ministry of Public Works (ΥΔΕ.) for the Master Plan of the capital (titled ‘Athens and once again Athens’) (Τριποδάκης, 2014) (Figures 10 & 11). ΥΠΕΚΑ commissioned a team from the National Technical University (ΕΜΠ) in 2010 to probe the idea of a partial pedestrianization of Panepistimiou Street (Figure 12) and to provide scenarios for extending the tram line from Syntagma to Parissia (ΥΠΕΚΑ and ΕΜΠ 2011). Despite the freeze on the project [7] (Καραμανώλη, Λάλος , 2014) the debate regarding the pedestrianization of Panepistimiou street reached immense proportions (Πορτάλιου, 2011, Χατζημιχάλης, 2011) and had a huge political and urban planning impact for two major reasons. First of all, it became a launching pad to deepen public debate on issues regarding the design of public spaces in the capital. At the same time it also sparked a debate about the role that public spaces can play in transforming the city’s image as well as what social role these spaces can play

Figures 10 & 11: Panepistimiou street before and after its proposed pedestrianization in the 1983 Master Plan

Source: Newspaper Ταχυδρόμος [date????]. S. Koulis archive

Figure 12: Photorealistic depiction of Panepistimiou by the OKRA team, winner of the Rethink Athens competition

Source: OKRA (2012)

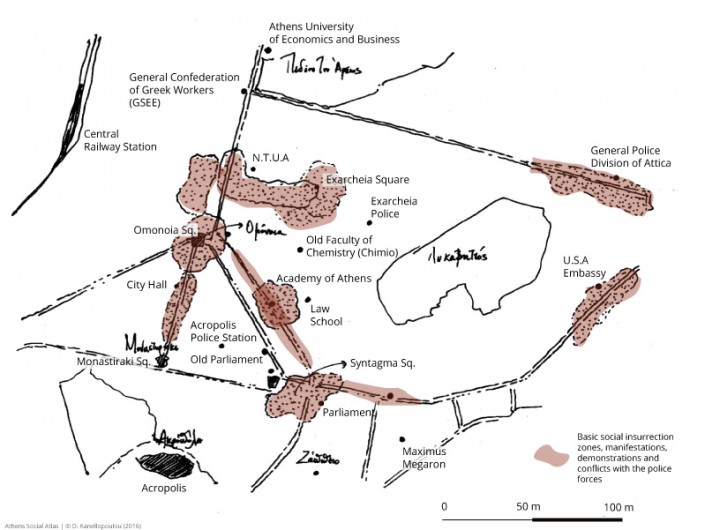

The map of pedestrianisation projects completed in the historical centre of Athens from the 1970s to the present (Map 1, Graphs 1&2), shows they are concentrated in areas directly connected to significant administrative, tourist and financial institutions (Map 3). The location of Panepistimiou Street is of particular symbolic significance concerning its social role as a public space. This road is a natural boundary among neighbourhoods that are significant in terms of tourism (Plaka, Monastiraki, the Commercial Triangle, Acropolis) and neigbourhoods that have mixed functionality, including middle class residential areas, civic buildings (schools, associations, etc.) and artistic locales (bookshops, libraries etc.). The thoroughfare itself has traditionally been a place of political discussion and expression and connects two of the city’s most historical squares.

Map 3: The symbolic and functional importance of Panepistimiou street in the centre of Athens in respect to areas of economic, political cultural and tourist interest

Conclusion

Since the end of the 1990s, pedestrianization on a small scale as a means of improving the urban environment in individual neighbourhoods has been put on the back burner of restoration of public space policies. On the contrary, large scale restoration has been promoted by the Ministry and the Municipality (Σταυρογιάννη, 2014) [8]. Despite the general rhetoric of the government regarding the significance of reclaiming the streets for the inhabitants, walking is still not an easy task in many parts of pedestrianized streets of Athens [9].

At the same time, the spread of different political movements [10], who reclaim public spaces for inhabitants (Καβουλάκος, 2013), as well as restoration policies on a large scale in historical districts and in residential areas has given rise to many questions and queries as well as to the need for public debate on whether policies should focus less on the pros and cons of particular projects’ implementation, and more on residents and citizens’s behaviors and needs who, apart from being the immediate beneficiaries of these projects, are also the creators of public space through their daily practice.

Acknowledgements:

A large part of the data presented in this article is based on interviews and unpublished material from the personal archives of the interviewees. As a result I would like to thank the following: Stratis Koulis, Tasia Lagoudaki, Stefanos Manos, Nouli Melampianaki, Elia Iatrou, Elli Papakonstantinou, Anna Skiada, Vaya Touri and Alexandros Tripodakis. I would also like to thank Stavros-Nikiforos Spyrellis for his diligence on maps 1 and 2 which accompany this text.

[1] Two units within the Ministry of Planning and the Environment (ΥΧΟΠ) are responsible for public space works: the Direction for Urban Planning and the Special Service for Public Works for the Upgrading of Free Public Spaces and Area Renewal (ΕΥΔΕ-ΑΕΚΧΑΠ) (ΦΕΚ 68/Α/1978).

[2] The perimeter was delimited in 1979 (ΦΕΚ 567/Δ/1979).

[3] See the program of the Company for the Unification of Archaeological Sites (ΕΑΧΑ) published in ΦΕΚ 909/B/1997.

[4] The Ministry of the Environment and Energy (ΥΠΕΚΑ) initiated the revision of the legal frame concerning the funding and implementation of public works (see Law 4014/2011 and mainly article 29, complemented by the articles 2 and 2α of Law 3316/2005).

[5] Project for the remodelling of a broad zone around Panepistimiou street. The project is adopted by the Ministry of the Environment and Energy (ΥΠΕΚΑ), the company Attiko Metro and the Ministers of Finance and Development.

[6] After 2008, the Municipality of Athens reduces expenses for the design of new public spaces and uses the funds to maintain and clean the ones that already exist. Personal interview with Elie Papakonstantinou (02/07/2014).

[7] The funding was rejected from the European Commission, because the investments required have no returns for the public sector and this was considered as an important disadvantage given the circumstances of the economic crisis.

[8] See the project Relaucnhing Athens (www.cityofathens.gr) of the Municipality of Athens.

[9] Personal interviews with Ilias Nomikos (20/05/2013), Dora Fardela (21/08/2013) and Elsa Tsekoura (04/08/2012).

[10] I refer mainly to the Free Spaces movement (see the Observatory of Free Spaces in Athens-Attiki) and to a number of residents’ initiatives (e.g. Filopappou Hills https://filopappou.wordpress.com/).

Entry citation

Kanellopoulou, D. (2016) Pedestrianization in the centre of Athens: A brief history and some questions, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/pedestrianization-in-athens/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.66

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References.

- Ζήβας Δ (2006) Πλάκα 1973-2003. Το χρονικό της επέμβασης για την προστασία της παλαιάς πόλεως Αθηνών. Αθήνα: Πολιτιστικό Ίδρυμα Ομίλου Πειραιώς.

- Ζιαμπάκας Σ (2015) «Λίφτινγκ» στο ιστορικό κέντρο. Εφημερίδα των Συντακτών, Αθήνα, 6 Νοεμβρίου. Available from: http://www.efsyn.gr/arthro/liftingk-sto-istoriko-kentro.

- Καβουλάκος Κ-Ι (2013) Κινήματα και δημόσιοι χώροι στην Αθήνα: χώροι ελευθερίας, χώροι δημοκρατίας, χώροι κυριαρχίας. Στο: Κανδύλης Γ, Μαλούτας Θ, Πέτρου Μ, κ.ά. (επιμ.), Το κέντρο της Αθήνας ως πολιτικό διακύβευμα, Αθήνα: ΕΚΚΕ, σσ 237–256.

- Καλαντίδης Γ (1998) Η ενοποίηση των αρχαιολογικών χώρων της Αθήνας. Αρχιτέκτονες 11: 36–53.

- Καραμανώλη Ε και Λιάλιος Γ (2015) Οριστικό «όχι» ΣτΕ στην ανάπλαση της Πανεπιστημίου. Η Καθημερινή, Αθήνα, 6 Ιουνίου. Available from: http://www.kathimerini.gr/818146/article/epikairothta/ellada/oristiko-oxi-ste-sthn-anaplash–ths-panepisthmioy.

- Κεχαγιά Β (2011) Τρέχουν για λίφτινγκ στο Κέντρο. Τα Νέα, Αθήνα, 3 Μαϊου. Available from: http://www.tanea.gr/news/greece/article/4629071/?iid=2.

- Μιχαήλ Ι (1986) Το πρόβλημα της Πλάκας σε σχέση με τη σύγχρονη Αθήνα. Στο: Τα προβλήματα των ιστορικών κέντρων Ρώμης και Αθήνας, Αθήνα.

- Πορτάλιου Ε (2011) Είναι δυνατή η ρύθμιση του χώρου σε εποχή γενικευμένης απορρύθμισης. Ενθέματα, Αθήνα, 4 Δεκεμβρίου. Available from: https://enthemata.wordpress.com/2011/12/04/portalioy/.

- Ρεμούνδου Α και Πανέτσος Γ (1994) Αναβάθμιση εμπορικού τριγώνου στο κέντρο της Αθήνας. Δεδομένα, αρχές σχεδιασμού, πρόγραμμα, μεθοδολογία. Στο: Ο δημόσιος χώρος της πόλης, Θεσσαλονίκη: ΣΠΕ – ΕΜΠ.

- Σταυρογιάννη Λ (2014) Πρόταση για την πεζοδρόμηση της Σταδίου. Η Αυγή, Αθήνα, 27 Φεβρουαρίου. Available from: http://www.avgi.gr/article/10810/1964405/protase-gia-ten-pezodromese-tes-stadiou.

- Τζαναβάρα Χ (2011) Τι αλλάζει η πεζοδρόμηση. Η Ελευθεροτυπία, Αθήνα, 12 Απριλίου. Available from: http://www.enet.gr/?i=news.el.article&id=266241.

- Τουρνικιώτης Π (2012) Μεταλλασσόμενοι χαρακτήρες και πολιτικές στα κέντρα πόλης Αθήνας και Πειραιά. Αθήνα.

- Τσιώρα Δ (1998) Χώροι για τους πεζούς. Κτίριο 106: 53–58.

- ΦΕΚ Β’ 909 (1997) Τροποποίηση της Κοινής Υπουργικής Απόφασης 69163/21.6.1995 και έγκριση του καταστατικού της ανώνυμης εταιρίας με την επωνυμία Ενοποίηση αρχαιολογικών χώρων Αθήνας Ανώνυμη Εταιρία. Ελλάδα.

- Χατζημιχάλης Κ (2011) Η πεζοδρόμηση της Πανεπιστημίου και άλλες πολεοδομικές φαντασιώσεις για το κέντρο της πόλης. Ενθέματα, Αθήνα, 15 Μαϊου. Available from: https://enthemata.wordpress.com/2011/05/15/hatzimihalis/.

- Fola M (2011) Athens City branding and the 2004 Olympic Games. In: Dinnie K (ed.), City branding: Theory and cases, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 112–117.

- Kanellopoulou D (2015) La marcheplurielle: aménagements, pratiques et experiences des espaces publics au centred’Athènes. Université Paris 1, Panthéon-Sorbonne.

Online sources

European Platform on Mobility Management, “Tems The EPOMM Modal Split Tool”, www.epomm.eu/tems