2017 | Jun

The gradual growth of large cities was considered an obstacle for the development of religious faith and this is why they were characterised as religious deserts where infidelity dominates (MacLeod 2005, 7-8). Despite the secularisation process that took place in western metropolises, and despite or perhaps because of globalisation, religion managed to preserve its presence in public space, although its political power has significantly diminished. Examining the West, Christianity might have lost the dominant place it used to hold, but other religions and new religious movements (NRMs) emerged during the 1960s and onwards. These altered the religious character of western cities to the point that today it is difficult for someone to trace a western society where the dominant religion in the public sphere is only one [1].

Regardless of talking about secular or post-secular (Baker 2011) cities, religion has kept its place in public space even through “hidden forms” (e.g. the informal prayer houses of Muslims in Athens) (Sakellariou 2011). The dynamic arrival and presence of Islam in the West triggered debates regarding the resurgence or the new visibility of religion (Hjelm 2015), as well as debates about the place of religion in public space, having as a main stake the construction of Islamic mosques. This has caused many juxtapositions and conflicts throughout Europe (Allievi 2009), something that inevitably occurred during the construction of said mosque in Athens. Religion nowadays, because of immigration, is considered to be “on the move” (Oosterbaan 2014, 593) and subject to changes. As a consequence, religion returns to public space in various ways, such as “getting out” of churches and temples (Becci et al. 2013, 8) (see for example the distribution of religious books and leaflets from Jehovah’s Witnesses and Mormons on the streets of Athens or in the public prayers of Muslims in open space, Photo 1).

Photo 1: Public prayer of Muslims, Kato Patissia, 2013

Source: A Sakellariou

Athens, as a European metropolis, is characterised by multi-religiosity even though this is not very obvious. The purpose of this article is to present through the available information – despite the lack of quantitative data – this religious plurality. As mentioned this plurality is not something new, since various religious communities (e.g. Protestants, Jews, Catholics, and Muslims) existed historically for centuries in the Greek capital, despite the dominance of the Orthodox element.

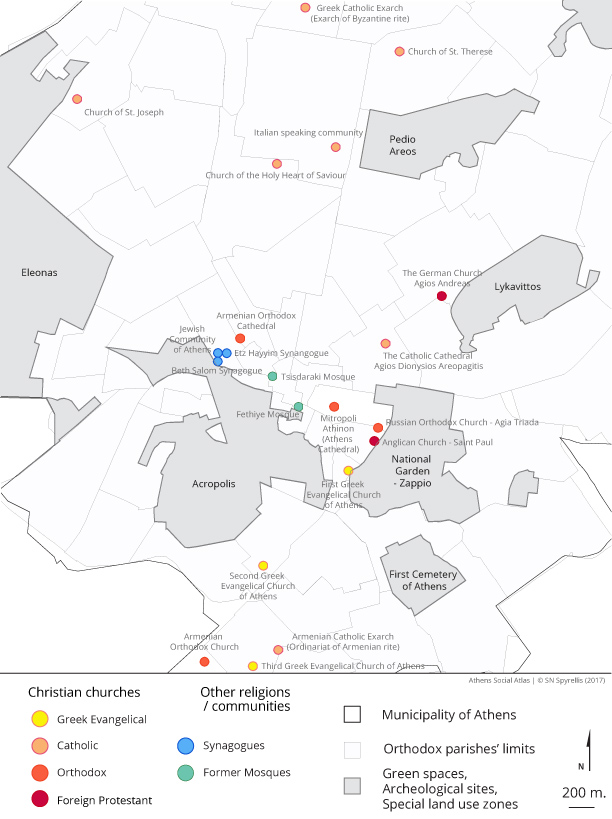

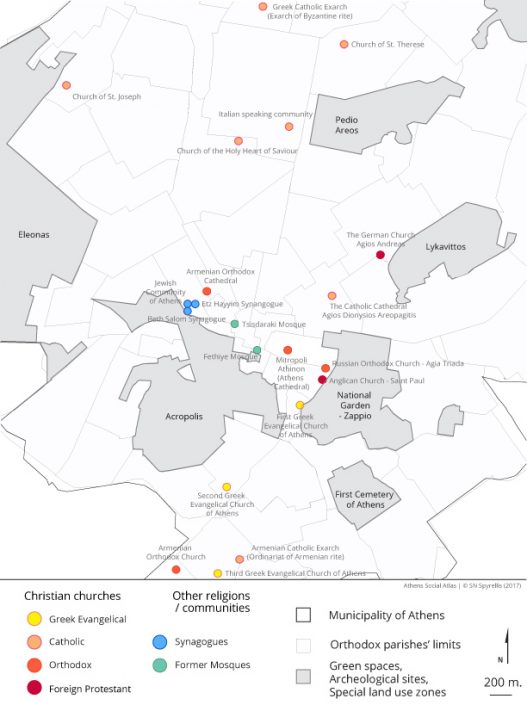

Map 1: Localisation of religious spaces of different religions and communities in the centre of Athens

The Orthodox dominance

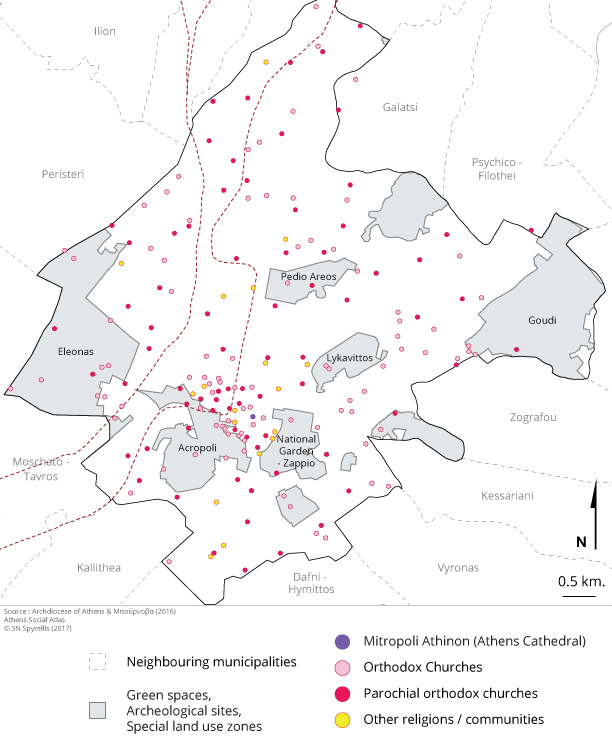

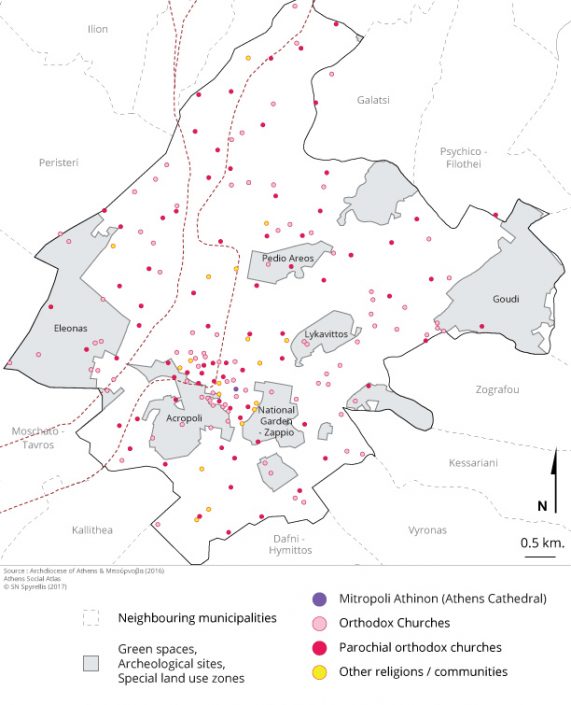

Even one who is not well aware of the Greek reality easily understands that the urban space of Athens is dominated by larger and smaller Orthodox churches (Map 2). In general, the Orthodox element in all of its forms (Greek, Russian, Armenian) (Photos 2, 3, 4) is incorporated in the urban tissue through various ways and constitutes the prevailing religious form that is visible to every observer.

Maps 2: Localisation of religious spaces in the Municipality of Athens

Photos 2, 3 and 4: The Cathedral of Athens, The Russian Orthodox Church and The Orthodox Armenian Church in Neos Kosmos

Source: A Sakellariou

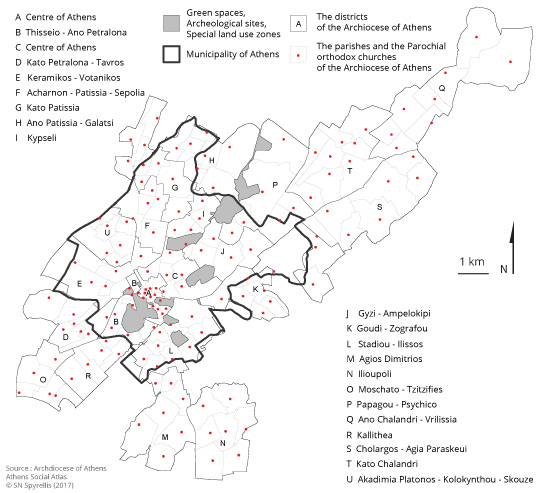

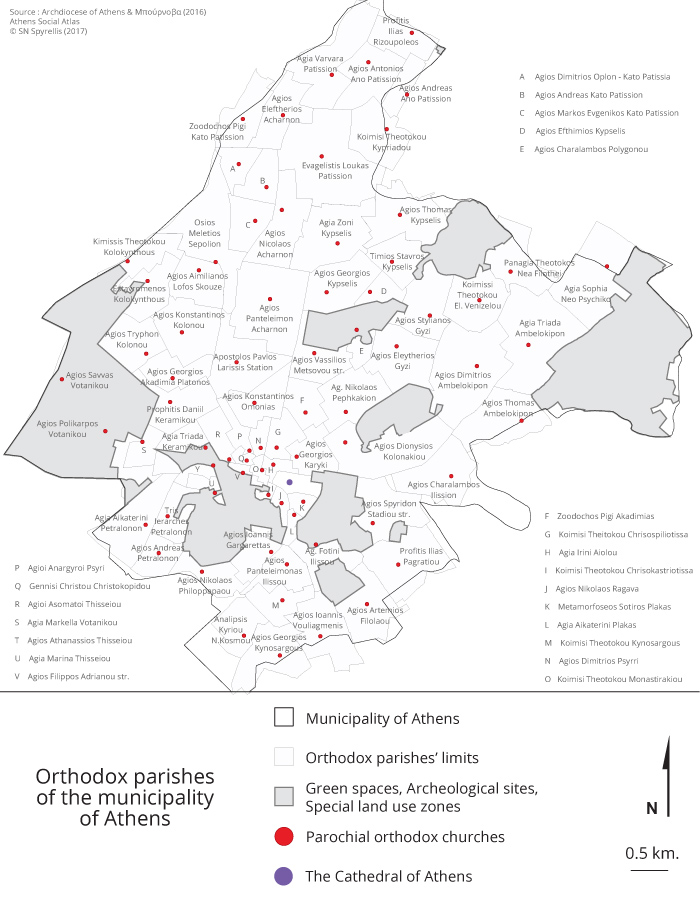

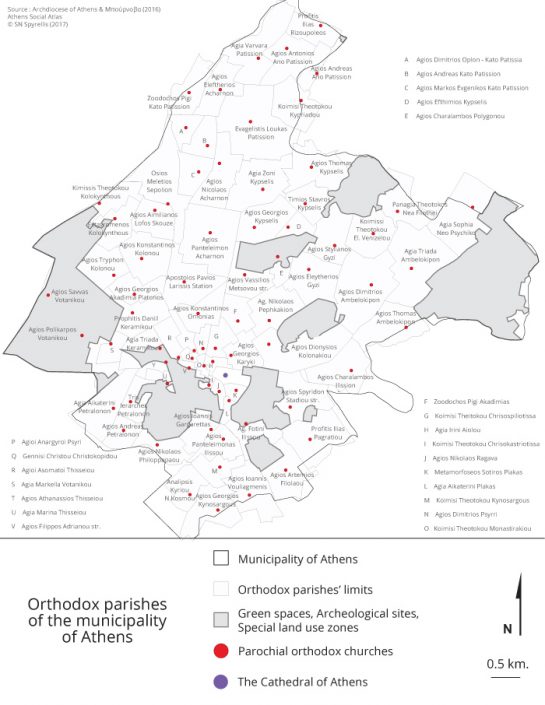

According to the Archdiocese of Athens, 145 parishes, divided among 21 districts, operate within the city region (Maps 2 & 4). These are illustrated on an analytical map followed by contact details [2]. Apart from parish temples, smaller churches are scattered throughout the city, like, for example, the one of Aghia Dynami situated beneath the building of the former Ministry of Education on Mitropoleos Street. In the Archdiocese of Athens seven monasteries and Holy hermitages exist, four of which are within the boundaries of the Municipality, thus constructing a type of in-world asceticism. This is a very interesting fact if one considers that the logic of monasteries and hermitages was to be situated far away from large cities.

Map 3: The 21 districts and the 145 parishes of the Archdiocese of Athens

Map 4: The parishes in the Municipality of Athens

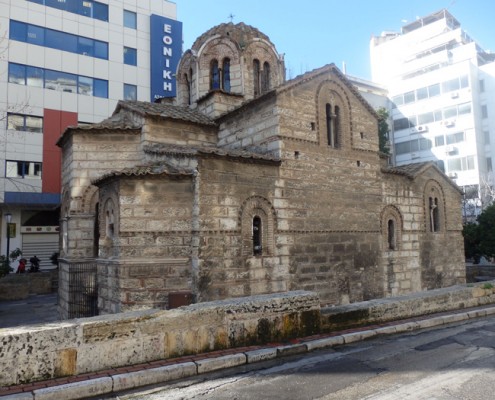

Within the city centre of Athens, on bustling and commercial streets, one can find many historical churches of the Byzantine or the Ottoman era. One such example is Kapnikarea or, as the church’s official name is, “The presentation of the Virgin Mary”, a church with old Christian columns dating back to its initial construction in the 11th century (based on a previously existing church of the 5th century) [3]. This church has faced the risk of demolition twice in history (1834, 1863), but eventually managed to keep its place in the city becoming, in modern times, a landmark and meeting point on the commercial street of Ermou (Photo 5). The church of Aghioi Theodoroi in Klafthmonos square of the same period (11th century), is of particular architectural importance, since, based on continuous archaeological excavations, it was discovered that it has been built over previously existing tombs of the Roman era (Photo 6).

Photos 5 & 6: The church of Kapnikarea and The church of Aghioi Theodoroi

Source: A Sakellariou

In many cases, Christian churches have been built on the relics of ancient temples and holy places. This constitutes a common practice of religions as they started to gain power and dominance on the social and political level. This domination is clearly illustrated in public space where every new religion gradually erases the traces of previous ones. Besides, debates or even violent conflicts over holy places in neighbouring locations, are common in many cases all over the world (Kong and Woods 2016, 20-24). An Athenian example is the small temple of Aghios Ioannis tis Kolonas (St. John of the Column) which is near Omonoia square, on Evripidou Street, and is placed on an ancient sanctum of Asklepios. A distinctive feature of the temple is a column of Korinthian style which protrudes from the church’s roof (Photo 7).

Photo 7: The church of Aghios Ioannis tis Kolonas

Source: A Sakellariou

The Catholic presence

The presence of the Catholic Church in Athens goes back to the era of the fourth crusade and the foundation of the Catholic archdiocese in 1205, even though it is argued that catholic communities existed since the 9th century. Catholics are the second largest Christian community in Athens after the Orthodox. Official statistical data on the number of Catholics are not available. According to unofficial estimates, Greek Catholics are approximately 50,000, though since the 1990s their total number increased because of the arrival of many immigrants (mainly from Poland and the Philippines). As a consequence, today their total number is approximately 250,000 [4]. The vast majority live in Athens and in the broader region of Attica, although, traditionally, communities of Greek Catholics have pre existed in the Ionian Islands and in the Cyclades.

Photo 8: The Catholic Cathedral, Aghios Dionysios

Source: A Sakellariou

Today in the Municipality of Athens one can find six Catholic parish churches and chapels, while the cathedral of Catholics in Athens is the church of Aghios Dionysios on Panepistimiou Street established in 1865 (Photo 8). Every Sunday, but also during the important holidays, the church is full of Catholics from around the world, a typical feature of the transformation of the composition of the catholic population during the last two decades. Like the Orthodox, the Catholic Church has nine holy monasteries in the centre of Athens and some others in the broader region of Attica (Piraeus, Psychico, Kifissia, etc.). The presence of the Catholic Church in public space is documented also through the ownership of its own foundations, cultural centres and schools like the Ursulines and Leonteios. It is worth mentioning the presence of the so-called Greek-rhythm Catholics or Unites, as they are called, who keep full communion with the Vatican, follow the dogmas of the Catholic Church, but keep the traditions and the church calendar of the Orthodox Church. This community draws its origin from the unification of the two Churches (Orthodox and Catholic) after the Ferrara-Florence Council in 1439 and its cathedral is located on Acharnon Street.

The ‘unknown’ Protestants

One of the less known religious communities of Athens but also of the whole of Greece, is that of the Greek Evangelicals or Protestants. The wider Protestant presence in Athens and in Greece commenced shortly after the Revolution of 1821, through the missions that were sent mainly from the U.S.A. towards the wider East Mediterranean and Middle East regions. However, the official appearance of the Greek Evangelicals took place in 1858 with Michael Kalopothakis, who published the periodical named “The Star of the East”. The first Greek Evangelical Church was constructed in 1871 and still operates in the same place, on Amalia Street, opposite Hadrian’s Gate (Κυριακάκης 1985). It should be mentioned that at the time of the construction, the church was considered to be at the city boundaries, since Athens was much less extended than today (Photo 9).

Photo 9: The first Greek Evangelical Church

Source: A Sakellariou

Greek Protestants are not many and if all the denominations and dogmas are considered (Baptists, Pentecostals, etc.) there are approximately 25,000 followers, most of them living in Athens. The number of Greek Evangelicals increased after the arrival of the Asia Minor refugees in 1922, where many evangelical communities existed. Because of this arrival and increase in numbers, two additional churches were built, the second and the third Greek Evangelical Churches, not far away from the first one. The second is located in Koukaki (Photo 10), on Zinni Street and the third in Neos Kosmos, on Heldreich Street. In addition, in the Municipality of Athens and in neighbouring municipalities, branches of the first Church are operating. Examples can be found in Exarcheia and in Glyfada. Independent churches also exist, like in the Piraeus region.

Photo 10: The second Greek Evangelical Church

Source: A Sakellariou

In the urban space of Athens and more particularly in the city centre, apart from the Greek Evangelical Churches, there are two foreign Protestant churches. The first one is the Anglican Church (Photo 11) on Philellinon Street constructed from 1838 to 1843, based on the design of the Greek Architect Kleanthis and executed by the Danish architect Hansen. The second is the German Church on Sina Street of a more modern style whose construction started in 1931 and was inaugurated in 1934 (Photo 12).

Photos 11 & 12: The Anglican Church and The German Church

Source: A Sakellariou

The Jewish community of Athens

The Jewish community of Athens is one of the oldest and more historic communities of the city with the first references traced back in ancient times and more particularly in the 1st century B.C. New references are found later on during the Ottoman rule, while many expatriated Jews from Spain arrived in Athens from 1492 onwards. Although during the 1821 revolutionary years the Jewish community of Athens was dissolved, it started to be reconstituted after the establishment of the Greek state and was officially recognised in 1889. The presence of the Jewish community in Athens grew significantly after the Balkan wars through the arrival of many Jews from Asia Minor and from Thessaloniki. After WWII the Jewish community of Athens is the largest Jewish community of Greece with approximately 3,000 members.

The first synagogue in Athens, Etz Hayyim, was built in 1905 on Melidoni Street in Thisseio (Photo 13). In 1935 a new synagogue was built, Beth Salom (Photo 14), which continues to function today and nearby is the Holocaust Monument (Photo 15). It is very interesting that before the establishment of the first synagogue there were some unofficial prayer houses, with one mentioned on Ivi Street, near Ermou Street, which functioned since 1886, while another one is mentioned in the Yiousouroum family place on Ermou and Karaiskaki streets.

Photos 13,14 and 15: The Etz Hayyim Synagogue, the Beth Salom Synagogue and the Holocaust Monument

Source: A Sakellariou

The presence of Jews today is not as territorially visible as it was during the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, when they played a crucial role in the commercial district of the city, an area called “the Jewish”. A typical remnant of that period, but also from the general presence of Jews in public space, is the region of Athens known as Yiousouroum. The name is derived from a Sephardic family from Smyrna, of which Bochor Yiousouroum came in Athens in 1863. Bochor was a tailor and opened a shop with clothes at the crossroads of Karaiskaki and Ermou Street, near the auction hall . Because at that time people did not have money to spend, Bochor would buy second hand clothes, convert them and sell them at the bazaar on Avissinias square every Sunday [5]. Afterwards, the business was inherited and expanded by his children who also became involved with antiques. As a consequence, the area became the heart of the Jewish community and in due course the family name was unofficially given to the wider area, despite the fact that since then many antique shops opened in the same district (Αδαμοπούλου και Σακελλαρίου 2003, 13-14).

Even though the Jewish community maintains cultural places and there is also the Jewish museum in Nikis Street at Syntagma Square with very interesting exhibits, their presence in public space is not comparable with Christian denominations regarding its visibility. One could argue that the Jewish presence in Athens, despite the existence of historical and monumental places is not very visible, and has become a kind of “hidden religiosity”.

The Muslim communities

Muslim populations have existed in the area of Athens since the Byzantine Empire era and also during the Ottoman rule. The contemporary Muslim presence in the area of Athens could be divided into two main categories, the natives and the immigrants and refugees, or, as it has often been called, the old and the new Islam (Tsitselikis 2012). The natives are primarily from the Muslim minority of Thrace and were gradually established in Athens since the 1960s in the area of Gazi (Gazochori), with the highest growth being documented in the 1970s. From the mid-1980s a second wave of internal immigration was observed in the same region but also in other neighbouring areas (Kerameikos, Metaxourgheio, Votanikos) (Antoniou 2003). The second category is the one of immigrants and refugees. Already from the 1970s but also later in the 1980s, many Muslims of Arab and African origins (e.g. Egyptians, Sudanese) arrived in Athens, most of them to study. This is why, since that time, there has been a popular demand for the construction of a mosque either in Maroussi or in Goudi, ideas that were never actually implemented. The presence of Muslims grew radically in the 1990s but mainly in the 2000s, when they started to arrive to Greece in mass numbers. Today the unofficial calculations estimate the Muslim population of Athens at approximately 300,000 [6].

The muslim majority nowadays resides in the centre of Athens and more particularly close to specific subway stations (Kato Patissia, Aghios Nikolaos, Attiki, Neos Kosmos, and elsewhere), but in other parts of the city as well (e.g. Kypseli) . Most of their unofficial prayer houses are found there as well. Most of these places are either illegal or they function having a different type of permit e.g. of a cultural centre or an association which also includes a prayer house. Usually they are placed in basements or old garages and storehouses with the exception of a large place in Moschato which belongs to the Arab-Hellenic Centre for Culture and Civilization and was built in an old factory with private funding (Photo 16). There are about 100 such places around the region of Attica, while according to other estimations there are about 60, because during the last years many of them were shut down due to the economic crisis and resulting financial problems (Photo 17).

Photos 16 and 17: The mosque in Moschato and a mosque in Neos Kosmos (Muslim Association of Greece)

Source: A Sakellariou

In the public space of Athens there are also many Ottoman monuments which document the Muslim presence throughout the city. Typical are the two mosques in the historical centre of Athens. The first one is the Fethiye Mosque in the Roman Agora which was recently renovated and will function as an exhibition place (Photo 18). Its construction is placed between 1668 and 1670 over the ruins of an unknown Byzantine temple of the 8th – 9th century. The second one is the mosque of Tsisdaraki or Tzistaraki (or the mosque of the Lower Fountain or of the Lower Bazaar Market) which is situated in Monastiraki square and was constructed in 1759 by the Ottoman governor of Athens and was also named after him (Photo 19). Nowadays it functions as cultural space- part of the Museum of Greek Folk Art. Apart from the existing prayer houses, another issue regarding the presence of Muslims, is their public prayers in open spaces, especially during Ramadan (e.g. The Olympic Stadium, Peace and Friendship Stadium, the University Propylaea) or during other holidays, like Ashura of Shia Muslims. Muslims are the second largest religious community, however, they have never acquired the relevant place in public space, because, despite their strong public presence, they are rather treated as an invisible religious group.

Photos 18 and 19: The Fethiye Mosque and The mosque of Tsisdaraki

Source: A Sakellariou

Other religious communities

Apart from the aforementioned recognised religions, many other smaller religious communities, older and newer ones, also exist within the urban tissue of Athens. Jehovah’s Witnesses (Μαυρολέων 2003, 58-63) for example, maintain many assembly places or Kingdom Halls, as they call them, and they are openly active in public space through the use of stands with leaflets and publications for the promotion of their religion. They first appeared in Greece at the beginning of the 20th century and today they are approximately 20,000, organised in about 350 churches, most of them situated in Athens. There is also the Church of Later-Day Saints (Mormons), whose first members appeared in Greece in the beginning of the 20th century, although the first official mission to Greece was organised in 1990 and today they reach 759 members [6]. At the same time and because of the intense immigration waves of the last years, Sikh and Hindu communities have developed, though their majority is found outside the city centre in other regions (Megara, Evoia, Voiotia, Marathonas) (Παπαγεωργίου 2011, Christopoulou 2013). Finally, other communities active in public space are people from various groups following the ancient Greek religion [7] organising open events at the temple of Olympian Zeus near Hadrian’s Gate and elsewhere, but also Greek Buddhists whose first organised appearance was in the middle of the 1970s, who were recognised by the Ministry of Education as a religious community in 2001 and number around 1,000 throughout the country and operate their own centres within the city (Photo 20) [8].

Photo 20: Buddhist centre in Athens

Source: A Sakellariou

All of the above prove that Athens is characterised by a religious variety, either prevailing and visible or hidden and invisible. The Orthodox religion is still dominant but there are other religious groups which claim their own place in public space, which historically has been a crucial subject of peaceful or even violent confrontation among religions. Bearing in mind the question of whether Athens was ever a secular city in order to characterise it now as post-secular, the main observation is that the religious landscape of the city is being transformed and will probably continue to do so even more in the future.

[1] I would like to thank those who helped me during the preparation of this article providing me with information and giving me the opportunity to take photographs of religious places. More particularly I would like to thank Mr. Naim Elgadour, from the Muslim Association of Greece, Mrs Taly Mair and Mr. Zozef Mizan from the Jewish Community of Athens, Mr. Halid Tribis from the Arab-Hellenic Centre for Culture and Civilization, and Mr. Giorgos Diakofotakis from Greek Buddhists, “The Diamond Way”. I would like also to thank Dr. Robert Hill for editing the English text.

[2] http://iaath.gr/enories-iaa και http://iaath.gr/enories-map

[4] http://www.cathecclesia.gr/hellas/

[5] http://www.kathimerini.gr/835870/article/politismos/polh/to-paramy8i-twn-gioysoyroym

[6] https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/256407.pdf

[7] http://www.mormonoi.gr/about

[9] There are many Buddhist schools but one of the oldest ones is the Diamond Way. http://www.diamondway-buddhism.gr/centers/athens/

Entry citation

Sakellariou, A. (2017) Religion in the city: Religious diversity in urban space, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/religion-in-the-city/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.73

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Αδαμοπούλου Α και Σακελλαρίου Α (2003) Ο Ελληνικός Εβραϊσμός Σήμερα: Η Ισραηλιτική Κοινότητα της Αθήνας. Πάντειο Πανεπιστήμιο.

- Κυριακάκης Μ (1985) Πρωτοπορεία και Πρωτοπόροι. Αθήνα: Αστήρ της Ανατολής.

- Μαυρολέων Μ (2003) Οι μάρτυρες του Ιεχωβά: Mια κοινωνιοψυχολογική προσέγγιση. Πάντειο Πανεπιστήμιο.

- Παπαγεωργίου Ν (2011) Θρησκεία και μετανάστευση. Η κοινότητα των Σιχ στην Ελλάδα. Θεσσαλονίκη: Κορνηλία Σφακιανάκη.

- Allievi S (2009) Conflicts over mosques in Europe: Policy issues and trends. London: Alliance Publishing Trust.

- Antoniou D (2003) Muslim immigrants in Greece: Religious organization and local responses. Immigrants & Minorities, Taylor & Francis 22(2–3): 155–174.

- Beaumont J and Baker C (eds) (2011) Postsecular cities: Space, theory and practice. London: Continuum.

- Becci I, Burchardt M and Casanova J (eds) (2013) Topographies of faith: Religion in urban spaces. Leiden, Boston: Brill.

- Christopoulou N (2013) ‘Sweet jail’: The Indian community in Greece. Florence. Available from: http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/29506/CARIM-India-2013_44.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Hjelm T (ed.) (2015) Is God back?: Reconsidering the new visibility of religion. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Kong L and Woods O (2016) Religion and Space: Competition, Conflict and Violence in the Contemporary World. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Mc Leod H (ed.) (2005) European Religion in the Age of Great Cities: 1830-1930. London: Routledge.

- Oosterbaan M (2014) Public religion and urban space in Europe. Social & Cultural Geography 15(6): 591–602.

- Sakellariou A (2011) The ‘invisible’ Islamic community of Athens and the question of the ‘invisible’ Islamic mosque. Journal of Shi’a Islamic Studies 4(1): 71–89.

- Tsitselikis K (2012) Old and New Islam in Greece: From historical minorities to immigrant newcomers. Leiden, Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.