An alternative approach to the 1833 plan of Athens

Karidis Dimitris

History, Planning, Social Structure

2019 | Jun

The approach focuses on the social character of the 1833 plan of Athens (by Kleanthes and Schaubert). Social analysis refers to both sides, to the authors of the plan and to the broader social context. With regard to the authors: a counter-claim is advanced contrary to the prevailing understanding of their proposal by means of stereotypical geometric figures which, once they are put on paper, supposedly, justify the design procedure itself (cyclical explanation). On the contrary, the approach in this paper claims that the field work carried out on the built up space of late Ottoman Athens, by the authors of the plan before they became engaged in the new plan, and the understanding of this environment, acquainted them with significant dimensions of the design procedure they should follow. At the same time, their experiences acquired both through their education in Berlin as well as their fruitful visits in Rome are considered to have decisively affected the understanding of the social dimension of their future proposal. In regard to the broader social context, the emphasis placed in the present paper on antithetical concepts such as community and society, tradition and modern life, public and private sphere of life, indicate the true reasons for the objections raised against the plan and its replacement by the Leo von Klenze plan. The claim that the real estate problems which arose out of conflicting interests among different groups of citizens were of primary importance is denounced. In a town, where the traditional administrative system was still in practice in 1833, where the structure of daily life had strong roots forged many years in the past, the belief that the previous antithetical conditions might be automatically overcome is rejected. Perhaps, on these same grounds, it may be supported that the 3d of September 1843 uprising, was vested with social characteristics, apart from its undisputable political significance.

Introduction – The written sources

Previous analyses to the first Athens plan were overwhelmed by a romantic and literally character of approach or were structured according to a travel-chronography basis – exceptions were few (Σουρμελής 1862, Φιλαδελφεύς 1902, Μπίρης 1933, Καρούζου 1934, Johannes και Μπίρης 1939). The first systematic references belong to the post mid-twentieth century period. Relative texts include: P. Lavedan (1952), Ι. Τραυλός (1960), Κ. Μπίρης (1966), Αθήνα-Ευρωπαϊκή Υπόθεση (1985), T.Hall (1997), E.Bastea (2000), Αλ. Παπαγεωργίου-Βενετάς (1999, 2001), D.Karidis (2014), Υ. Tsiomis (2017). Nevertheless, even under this category, the majority of historiographic analyses stand between history of architecture and urban history – ‘encyclopaedism’ is omnipresent: persons and chronologies are all powerful in the context of analysis and, thus, the modus operandi of the plan is lost. At the same time, as the plan is merely described and not explained, it is believed that it blindly follows design-clichés of the past, which are monotonously repeated from one publication to the other, as if they were self-evident and all-powerful synthetic tools. What is most astonishing is the atrophied dimension of social analysis, mainly as regards the narrow view under which the reactions against the implementation of that early plan are explained.

The ‘geometry’ of the Athens plan versus social reality

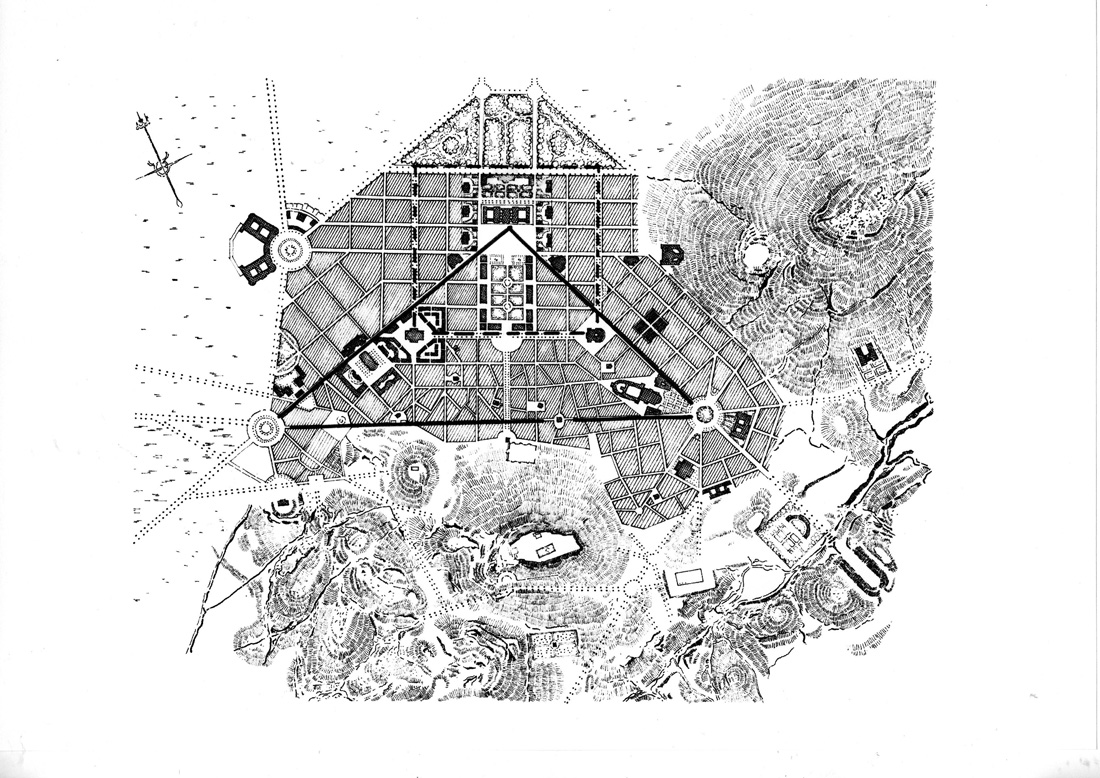

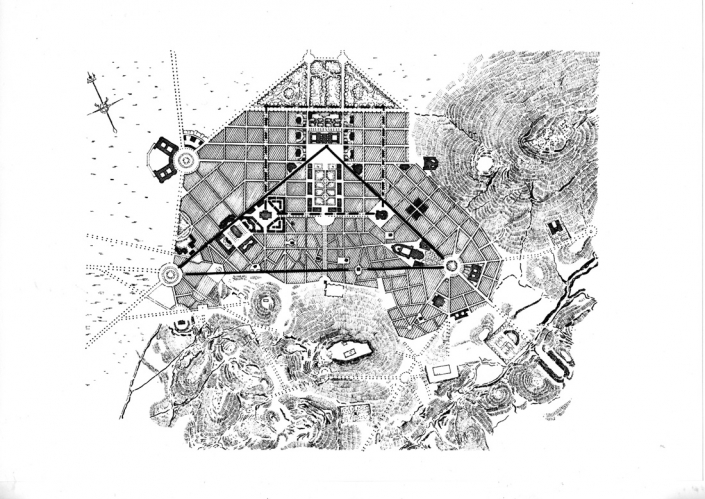

Notwithstanding occasional differences among them, the majority of the previous written sources converge, as regards an emphasis on the geometric characteristics of the urban form. The ‘geometry’ of the whole synthesis is usually understood under two well-defined forms (Figure 1) – an ‘almost’ isosceles, ‘almost’ right-angled triangle and an ‘almost’ rectangle (Αθήνα, Ευρωπαϊκή Υπόθεση : 93, Παπαγεωργίου-Βενετάς 2001: 67, Tsiomis 2017: 158). But, perhaps, this same ‘geometry’ can be understood under a different approach, revealing a different.

Figure 1: The Kleanthes-Schaubert plan of Athens (1833), including diagrammatic representations (source: re-drawing D.Karidis 2014, Fig. III. 2)

Let us consider axes, instead of geometric shapes, as the defining elements of the plan. Two of these axes appear to fit perfectly well within the existing situation, as regards the economic life and the social character of space) of pre-revolutionary Athens, depicted by Klenathes and Schaubert little before they submitted their planning proposal. These axes correspond to important gates of the town, defining directions to the Morea, to Elefsis and Thiva, and to the Mesogeia area. At the intersection of these same axes, the most important part of the political, the social and the economic life of the late-Ottoman Athens was located – namely the bazaar. Each of these axes was defined by two landmarks, selected on an equal basis from the periods of antiquity and the middle-ages.

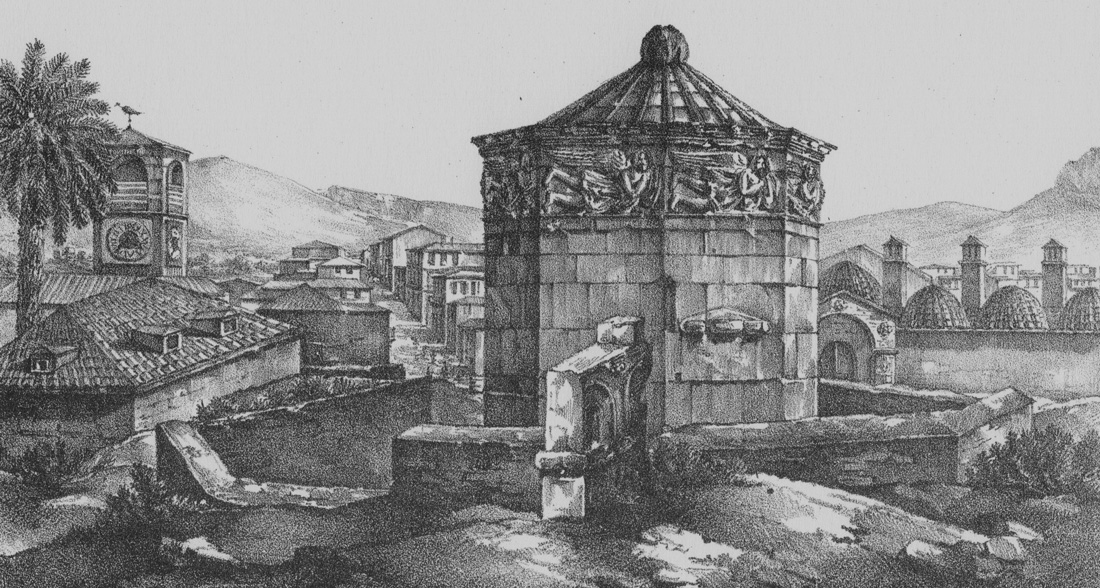

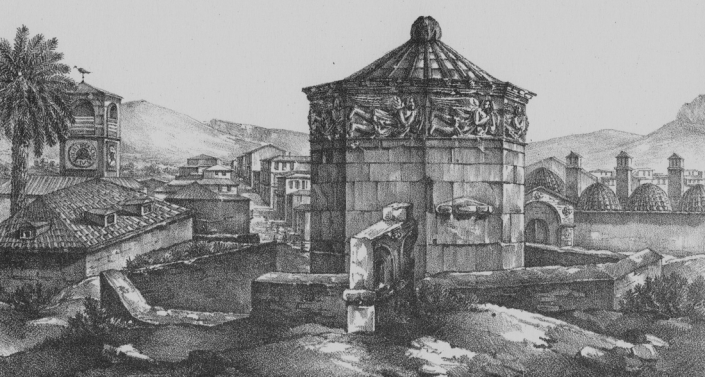

Figure 2: Eolou street is born (source: Lithograph, unknown artist, 1843, private collection)

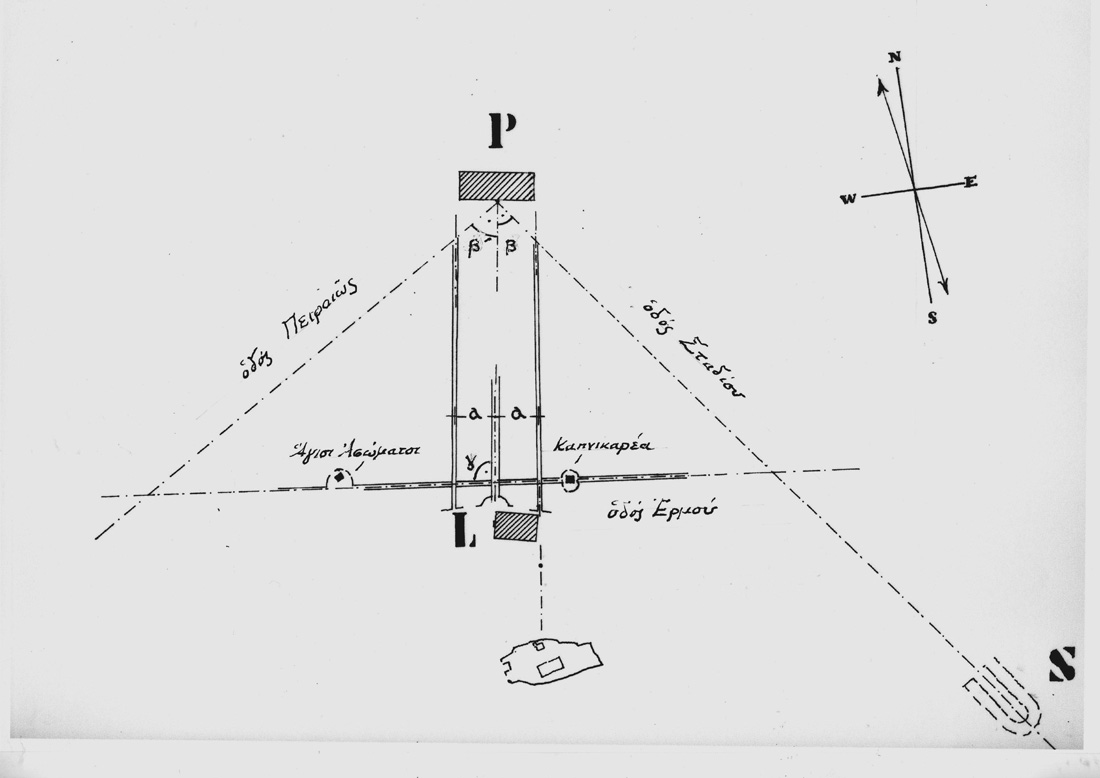

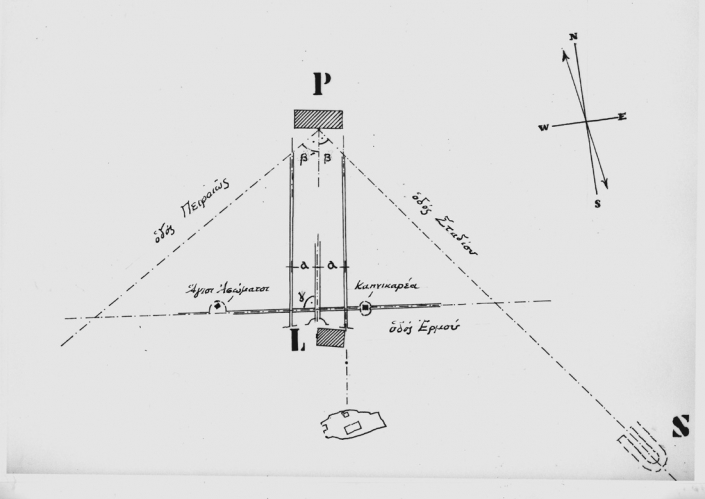

The north-south axis (Eolou Street) links the Erechtion with the Horologion of Andronikos (Figure 2). The south-west axis links Kapnikarea church with the church of Agioi Asomatoi. The specific selection of the north-south axis also explains the orientation set to the plan in relation to the Acropolis hill, diverging almost 150 from the North – a divergence which was, until now, left without any comment, or, thought to be the result of previous topographical corrections (Tsiomis 2017: 154). As for the other axis, in the eat-west direction, it intersects the north to south axis slightly diverging from a right angle. It is understood that this was so because the design concept in question is related to the overall design pattern suggested round each one of the two churches. And this design pattern is part of a romantic-classicist approach adopted in situ. So far, this numerical divergence has been left without any explanation (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The main design axes in the first plan, 1833 (source: author)

Within the existing town-planning analyses, the primary role of the north to south axis was given to Athinas street, and not to Eolou street, as it was previously suggested. It is thought that this was so because the plan gave specific priority to the role of Athinas street as the bisector of the top angle of the triangle. At the same time, one of the landmarks defining the direction of Athinas street was thought to be the Propylaia – what appears to be an absurd proposal. This is because the specific building complex on top of the Acropolis was (understandably) designed on the basis of a facial character, looking towards the west side of the hill, rather than supporting by itself a view from the north side of the hill [1].

Upon a second attentive reading of the geometrical synthesis of the 1833 Athens plan, one is inclined to point at the distance set between Eolou Street and Athinas Street, which is exactly the length of Hadrian’ s Library, an antique building complex which, just as it was the case with the Horologion, was widely discussed in the European travelogues of the 18th and the 19th century [2]. It is not accidental that the surface of Hadrian’s Library corresponds to the surface of the majority of urban blocks figuring on the first Athens plan! [3]

What remains to be explained is the choice made by the authors of the 1833 plan to draw Ermou Street through Kapnikarea church. The specific decision cannot be thought to be some kind of “mystery” (Tsiomis 2017: 154) [4]. We should rather turn our attention to Kleanthe’s and Schaubert’s journey, which was made right after they concluded their studies at the Berlin Baukademie. Part of that trip was a visit to Rome – what was a common practice for most of the architects, painters, etc. of the period. All available written sources do mention this visit, yet they do so rather briefly and ‘reluctantly’ (Bastea 2000: 73). Otherwise, these same sources put an emphasis on the acquaintance (very important, indeed) Kleanthes and Schaubert made in Rome of Karl Wilhelm Freiherr von Heideck (Παπαγεωργίου-Βενετάς 1999: 33) [5]. And yet, for those two young architects Rome was an open book of History of the City, the most valuable stimulus for the understanding of the Architecture of the City, the decisive intermediate between the education they received from Karl Friedrich Schinkel and the professional career they followed later. Indeed, Rome was the city which introduced pioneering urban interventions in the years which followed Pope Sixtus V, by the end of the 16th cent. (Gutkind 1969: 166). New thoroughfares in the city and obelisks had decisively articulated the built up environment and they had successfully managed to orientate the visitor by means of a “clearly organized sequence of purposeful architectural impressions” and not “a series of blunted visions of scattered houses, churches, and rolling countryside” (Bacon 1974: 136). The place occupied by Santa Maria Maggiore along the Strada Felicia, the apotheosis of baroque design (Rasmussen 1969: 50), was definitely not overlooked – and in this sense, the same place might be considered as the archetypal expression of the later choice to locate Kapnikarea church along the axis of Ermou street.

Nevertheless, Rome suggested one more provocative reading of its urban space: the Trivium of Piazza del Popolo. By the time the visit to Rome took place (1828) the series of urban interventions by Giuseppe Valadier had just been concluded there, including the semi-circular apses on the right and the left of the obelisk standing in the middle of the square, the connection of the same square with the Pincio gardens on the east, and the movement to the Tevere on the west (Bacon 1974: 155, 157). This is one more archetypal expression which the two young architects possibly recalled a few years later, while preparing the first Athens plan, locating the Palace on the top corner of the triangle and allowing for the main axes to radiate towards the Stadium, the Acropolis and Piraeus [6]. If examined under the previous syllogism, it appears that to look for the Trivium prototypes at Karlsruhe (Tsiomis 2017: 159) or to Versailles and St Petersburgh (Παγεωργίου-Βενετάς 1999: 266-267) was a rather unsuccessful (and all too easy) explanation.

The social and political context of the first plan revisited

Emperor Franz-Joseph, on the occasion of the urban interventions which took place in Vienna and Budapest in the middle of the 19th century, had mentioned three planning objectives: Erweiterung, Regulierung, Verschoenerung. The 1833 Athens plan included these same intentions – and, within this context, the existing analyses of this same plan more or less explain the specific planning proposal. Yet, one can claim that there are areas of analysis which have been overlooked, or, areas which have missed the ‘magnificence of explanation’ as they over-emphasized the ‘magnificence of geometry’. The following remarks try to overcome such a misunderstanding. The starting point is made by the plan’s final rejection, a few months only after its approval and the introduction of a new plan suggested by Leo von Klenze.

For the majority of the existing analyses of the first Athens plan, the epicenter of the reasons advanced for its rejection are the real estate problems which arose out of conflicting interests among different groups of citizens. The few systematic references on behalf of the social and political planning dimensions are overshadowed by what is commonly believed to be the “cultural tradition of the relation among the modern Greek society and the land property” (Μονιούδη-Γαβαλά 2017: 17).

The process of the implementation of the first plan was, by necessity, related with the overcoming of two sets of opposites – on one side, among ‘community’ and ‘society’, as these terms were first introduced by F. Tonnies’ Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft (Bottomore 1972: 39), and among ‘tradition’ and ‘modernism’. Both antithetic issues are incorporated in the process running from the post-capitalist period to the modern period (Karidis 2014: 245). ). In 1833, the traditional system of local administration was still in use (Γέροντας 1964: 13). The passage from experiencing the basic unit of the small parish community to an understanding of ‘privacy’, the latter understood as a set of rules of social organization adhering to the notion of a modern state, could not be ‘automatically’ concluded. To abandon all previous social and mental patterns of behavior would be synonymous to the destruction of an organic social cohesion (Figure 4). Even under the strictest stipulation of the new legal system it is absurd to believe that the passage from the medieval neighborhoods and the ‘unity in diversity’ inherent in them, to the early 19th century urban context, conceived on the basis of a theatrical maniera grande, might have been accomplished within a short period. A new architectonic/urban vocabulary had to be introduced within the borders of the newly formed urban environment.

Figure 4: Modern Athenians (source: Lithograph, unknown artist, c. 1840, private collection)

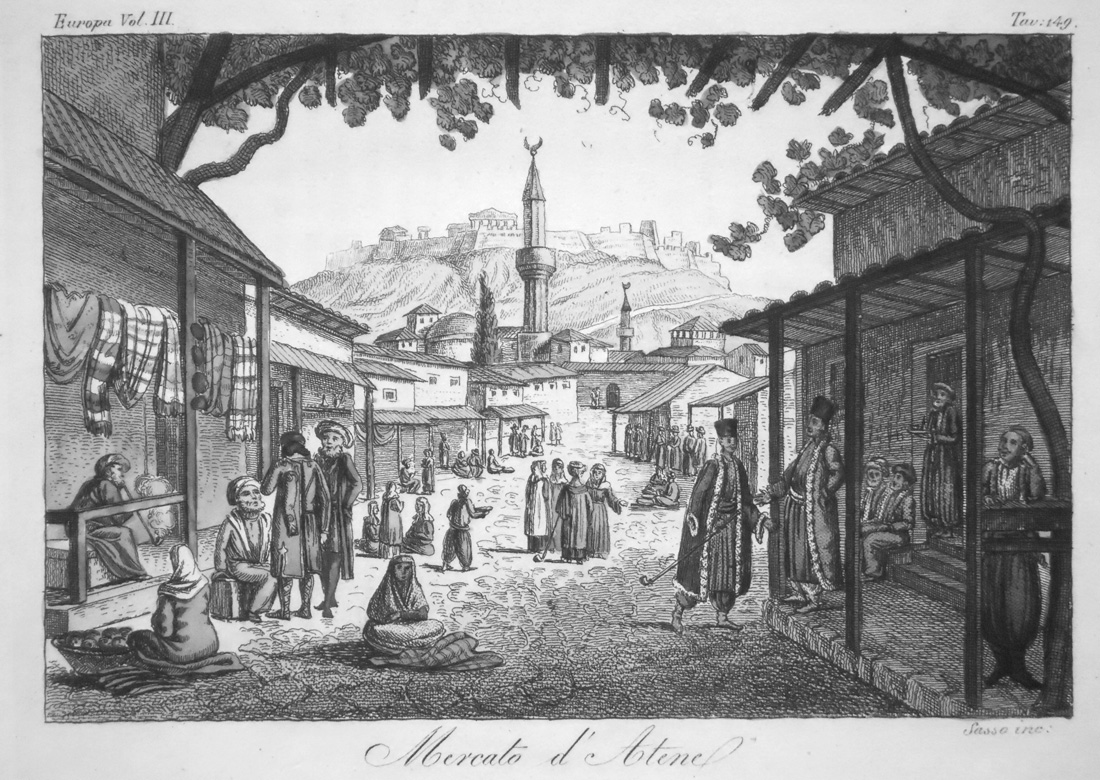

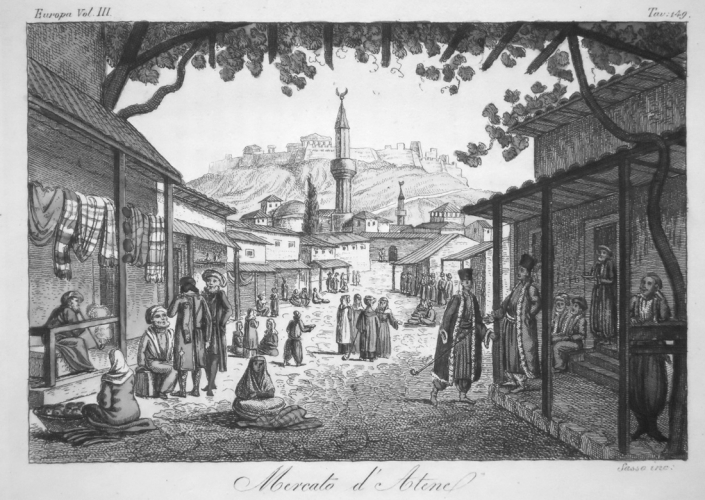

A break with the past was the condition for the new stratagems regarding the production of the built environment to be implemented. The idea of continuity of building fronts along the sides of a street and the new character of specific urban functions about to be introduced (e.g., in production and trade, with the passage from the oriental bazaar to a western-like commercial street), as well as the coming of new boulevards introducing the dramatic perspective of long-distance views, implied a new concept of city aesthetics – an altogether modern element (Figure 5) (Karidis 2014: 244).

Figure 5: Mercato d’ Atene (Source: G.Ferrario, Storia del Governo…di tutti Popoli antichi e Moderni, Firenze, M.DCCC.XXVIII)

So, the forced break with the past was necessary. It is for sure that the authors of the first Athens plan were not in possession of any ‘magic wand’ in order to implement their design proposal. In the early years of the capital city of the Hellenic state, it was out of the question that the members of a family living in a ‘traditional’ house might accept the new strict borders introduced (why?) among the private and the public sphere of life, to realize that they would no more (why?) experience the area in front of their house according to their ethos but according to decisions taken (why?) by a group of educated civil servants (whom they ignored). G.Finlay acerbically remarked that the citizens of Athens had “not seen the plan or been consulted on its practicability, let alone utility” (Finlay 1836: 95-96). On the other side, it is for sure that land speculation within the borders of the capital city was common practice. The same holds true as regards conflicts arising among, land owners who considered that in their vested interests were seriously threatened in the process of planning the new capital city, while the Government was unable to grant the required indemnities in the context of sharp land price increases (Morot 1873: 43-44).

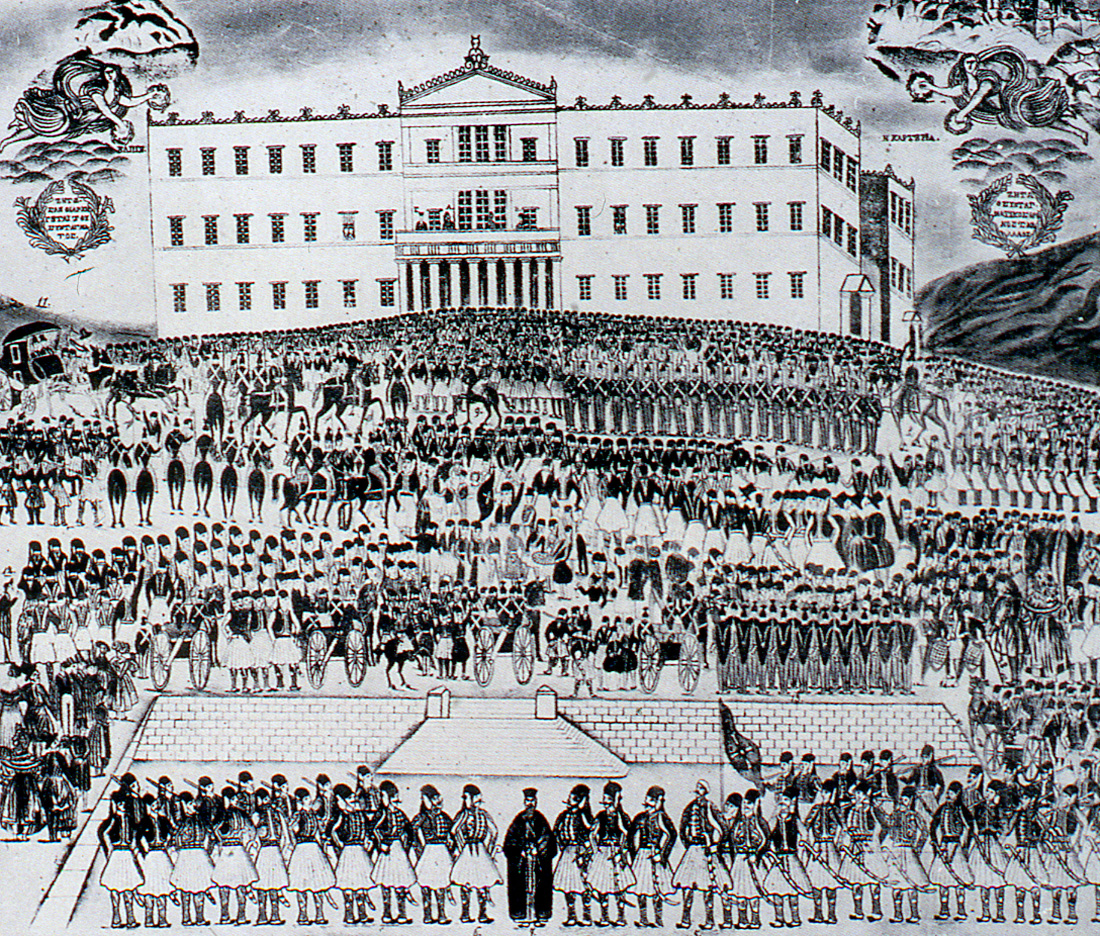

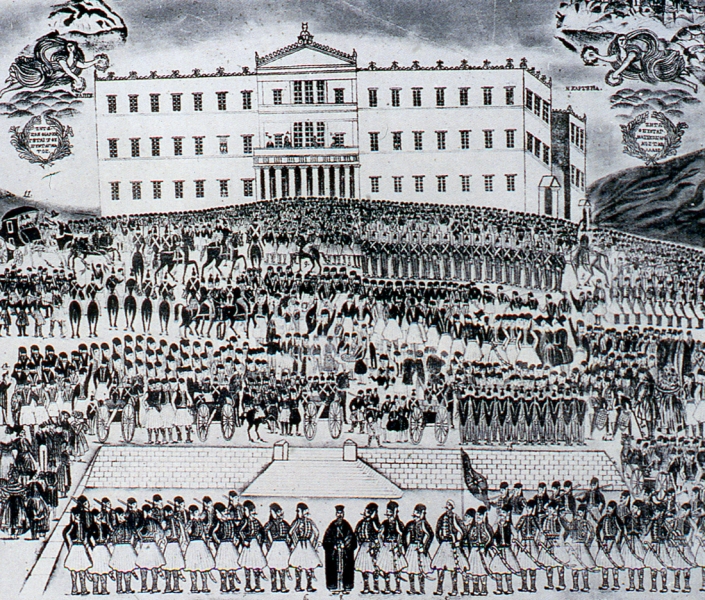

Figure 6: The 3rd of September 1843 uprising (source: Lithograph, unknown artist, private collection)

Within the previous analysis, it might be that the revolutionary movement of the 3d of September 1843, which is usually strictly examined under political conditions, should be (also) considered as a social and a psychological reaction of the small Athenian community to the ten-years pressing demands enforced against her. The official decree which commanded the implementation of the first Athens plan was, definitely, part of those pressing demands (Figure 6).

Excursus -K.Fr. Schinkels’ contribution to the plan

Schinkel’s drawing of the Royal Palace on top of the Acropolis proved to be a most provocative suggestion, so that, in the long run, any comments on the merits of the drawing itself have been overshadowed by controversial discussions on the true intentions of that suggestion (Kühn 1979: 511). A careful reading of the writings of the Prussian Oberbaudirektor reveals that the whole project had nothing to do with a plan intended to be implemented – it was a visionary suggestion (as his plan of Orianda Palace, in the Crimea also was, 1838), conceived in the context of exchanging views with Prince Maximilian of Bavaria as regards the ideal in architecture and, more specifically, the splendor of Greek architecture (Bergdoll 1994: 217). It is for the same reason that the belief, supposedly testifying that Schinkel’s participation in the preparation of the first Athens plan is impossible (implying that in the plan of Athens, ratified in 1833, the Palace was located in the town below the Acropolis), is absurd. On the contrary, there are strong arguments in favour of the teacher of Kleanthes and Schaubert having been involved in the elaboration of the Athens plan [7]. Such arguments have nothing to do with any ‘corrections’ Schinkel might have proposed to Schaubert upon the latter’s visit in Berlin. These arguments are based on three crucial remarks Schinkel must have advanced, towards his two former students, in correspondence with them between 1832 and 1833, ever since the early stages of the elaboration of the plan.

The first remark is related with the juxtaposition of the Acropolis and the Palace: the dialogue introduced between the seat of the Sovereign and the symbol of civilization had been already well established, in Berlin’s Lustgarten, only a few years earlier, when the Altes Museum was built facing directly the Emperor’s Palace (Bergdoll 1994: 73-86) [8]. Schinkel had been directly involved in the choice of the specific area for that Museum. In Athens, the same dialogue was introduced, in the other way round: the Acropolis (Symbol of Civilization and Demoocracy) came first and the Palace (symbol of the Sovereign’s power) came afterwards.

The second remark is related with the ‘Π’-shaped commercial complex, which was located along Athinas Street in the first Athens plan – in this case the architectural prototype might have been the Kaufhaus which Schinkel had suggested to be built in Berlin in 1827, when Kleanthes and Schaubert were students at the Bauakademie (Παπαγεωργίου-Βενετάς 2001: 75-76, Tsiomis 2017: 164). Even if Schinkel did not directly indicate the specific commercial complex, it is certain that the two young architects had good knowledge of it. It was common practice that great part of the educational material in use at said School of the Berlin Academy included the understanding of their tutors’ own projects.

The third remark refers to the trivium in Athens, formed by the axes radiating from the Palace [9], earlier commented.

As it is understood, the first and the second of the previous remarks constitute, so to say, the DNA of the first Athens plans! [10]

Even though these remarks, supposedly made by Schinkel have, so far, no written evidence to support them, they still retain their significance as challenging issues in the context of research.

[1] The specific building complex had an understandable facial character, looking towards the west side of the Acropolis, disregarding its view from the north. One only has to look at Leo von Klenze’s pencil drawing (1834) of the northern side of the Acropolis.

[2] Normally, it was the west side of the Library that was depicted in the drawings, the side which included the Propylon and the attached leaning against the wall. The most well-known among these drawings was the one by Le Roy (Les ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce, 1774).

[3] The dimensions of the Library of Hadrian are, approx., 76×115 m. The rectangular shape under which the Palace is depicted on the map by Klenathes and Schaubert is purely indicative. Such indicative plans were part of the Architektonisches Lehrbuch, by Fr.Weinbrenner (Tubingen, 1810-1819), a textbook for architecture, which must have definitely been known to the Baukademie students of architecture.

[4] One source is the exception to the rule, even though the meaning is rather unclear. K.Biris wrote: “They drive away (?) Ermou street from meeting Athinas street on a right angle, so that they might save (?) Kapnikarea [church]…” – our question marks (Μπίρης 1966: 29-30). In other bibliographical references on the subject, the fact that there is no comment whatsoever on this subject might imply that they consider the specific planning decision (namely the divergence from the right angle) as self-understood!

[5] That meeting was crucial for the two young architects, since it is following that meeting that they became acquaintained with Capodistrias, the Governor of Greece at that time, and, later, they were assigned the first Athens plan. The same stands true for K.Fr. Schinkel, some two decades earlier, when he met W.Humboldt in Rome, and, following that acquaintance, he ‘entered’ the Court of Prussia.

[6] Unless someone else indicated them the same Trivium solution (see following paragraph in the text)

[7] Karidis, https://www.blod.gr/lectures/to-allo-shedio-tis-athinas-tou-1833

[8] The great Ionic stoa on the front of Altes Museum and the central part of the building opening the view to the interior bore a symbolic expression of the social character assigned to Culture, far from the ‘conventional’ character of an Art Museum. (It is easy to identify two buildings of the same period with such a ‘conventional’ character: the Glyptoteque in München, designed by Leo von Klenze, in 1830, and the British Museum, by Robert Smirke, in 1827). In Berlin, the strict and ‘closed’ façade of the Palace was the perfect contrast to Schinkel’s museum. In Athens, where Schinkel never came, the symbol of Culture and Democracy was already in place. For Schinkel, it was only logical that the Palace should be located opposite it.

[9] The specific layout was discussed in a previous paragraph.

[10] Perhaps, this remark explains Leo von Klenze’s ‘insight’, when he was asked to replace Kleanthes and Schaubert plan with a new plan. Indeed, the location of the Palace in a different place was a direct attack upon the symbolism inherent in his adversary’s proposal.

Entry citation

Karidis, D. (2019) An alternative approach to the 1833 plan of Athens, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/an-alternative-approach-to-the-1833-plan-of-athens/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.89

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Γέροντας Δ (1964) Περί του εθιμικού δικαίου των Αθηνών της Τουρκοκρατίας και της Επαναστάσεως. Αθήναι.

- Καρύδης Δ (2018) Το «άλλο» σχέδιο της Αθήνας του 1833. Αθήνα. Available from: https://www.blod.gr/lectures/to-allo-shedio-tis-athinas-tou-1833.

- Μονιούδη – Γαβαλά Δ (2017) Σχεδιασμός και έγγειος ιδιοκτησία στην Αθήνα, 1833-1922. Αθήνα: Παρασκήνιο.

- Μπίρης Κ (1966) Aι Αθήναι από του 19ου εις τον 20ον αιώνα. Αθήνα: Έκδοσις του Καθιδρύματος Πολεοδομίας και Ιστορίας των Αθηνών.

- Παπαγεωργίου – Βενετάς Α (1999) Εδουάρδος Σάουμπερτ (1804-1860). Σιετή Τ (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Οδυσσέας.

- Παπαγεωργίου – Βενετάς Α (2001) Aθήνα. Ένα όραμα του κλασικισμού. Αθήνα: Εκδόσεις Καπον.

- Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού (1985) Αθήνα Ευρωπαϊκή Υπόθεση. Αθήνα.

- Bacon EN (1974) Design of cities. London: Thames and Hudson London.

- Bastea E (2000) The creation of modern Athens: planning the myth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bergdoll B and Lessing E (1994) Karl Friedrich Schinkel: An Architecture for Prussia. New York: Rizzoli.

- Bottomore TB (1972) Sociology. London: Unwin University Books.

- Finlay G (1836) The Hellenic kingdom and the Greek nation. J. Murray.

- Gutkind EA (1969) Urban development in southern Europe: Italy and Greece. New York: The Free Press.

- Hall T (1997) Planning Europe’s capital cities: aspects of nineteenth-century urban development. London: Routledge.

- Karidis D (2014) Athens, from 1456 to 1920, the Town under Ottoman rule and the 19th century Capital City. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Kühn M (1979) Schinkel und der Entwurf seiner Schüler Schaubert und Kleanthes für die Neustadt Athen. Berlin und die Antike, Berlin.

- Lavedan P (1952) Histoire de l’Urbanisme, Époque Contemporaine. Laurens H (ed.), Paris.

- Morot J-B (1873) Journal de Voyage Paris à Jerusalem. Paris: Imprimerie de J.Claye.

- Rasmussen SE (1969) Towns and Buildings. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Tsiomis Y (2017) Athènes à soi-même étrangère. Marseille: Parenthèses.