2023 | Dec

Introduction

To write the history of mass, and multi-faceted, house-production phenomena, guided as they are by a host of small private initiatives rather than state planning or big capital investments, unique case studies can be valuable but are not enough. Undoubtedly, in the absence of any centralized archive, case studies unpack crucial aspects of such phenomena. Architectural and urban historians who focus on housing, such as Gaia Caramellino, Filippo de Pieri, and Yael Allweil, have employed such microhistorical approaches in recent years, demonstrating their heuristic power (De Pieri, 2013; Allweil, 2017; Caramellino, 2019: 294-315; Μelsens et al, 2022). In the study of ‘antiparochi,’ the ‘land-for-flats’ trade-off contract which gained popularity in the Greek real estate after WWII—kicking off the spread of the typical Athenian condominium apartment buildings, known as the ‘polykatoikia’—, case studies challenge common assumptions about its grassroots nature and provide for a more nuanced understanding of architecture in the country (Kalfa and Alifragkis, 2022, Kalfa and Theodosis, 2022).

Housing, however, is, by nature, a quantity issue (Allweil, 2022), Patterns of action by a range of ‘agents’ as well as the spatial evolution of collectively produced residential types, that the polykatoikia is, can be researched only through large-quantity, long-term historical inquires. In this line, story recordings by groups that work on oral history at neighborhood scale recommend a more cohesive, and collective, history (a ‘history from-below’) of the intricate mechanisms of urbanization. Other tools, deeply entrenched in the field of architectural history, such as typological analyses so far employed in the study of vernacular architecture, have also enriched our understanding (Paschou, 2008; Woditsch, 2018).

More recent approaches that leverage large quantities of data and use geocoding through Geographic Information Systems (GIS) provide new perspectives in interpreting mass spatial, socio-economic, and typological transformations. The original research here presented, is an early glimpse into the manifold potentials stemming from spatializing a bulk of data pertaining to the post-war polykatoikia in Athens.

Sources and assumptions

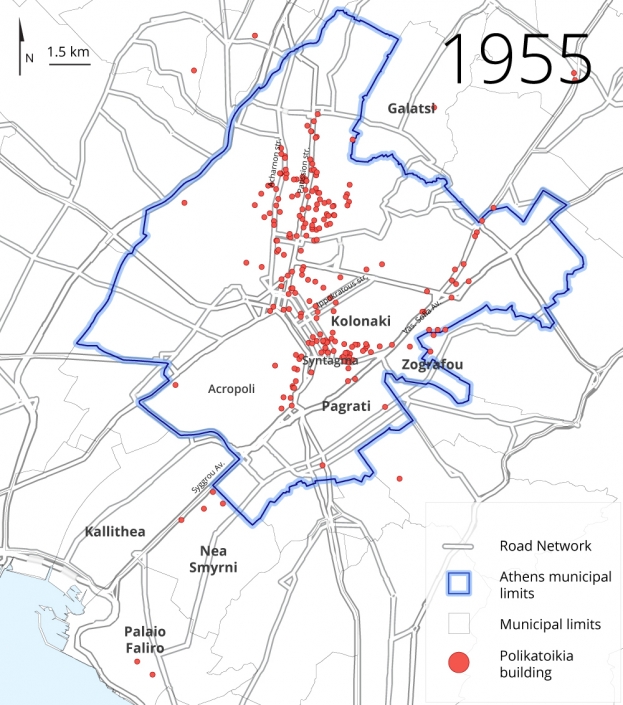

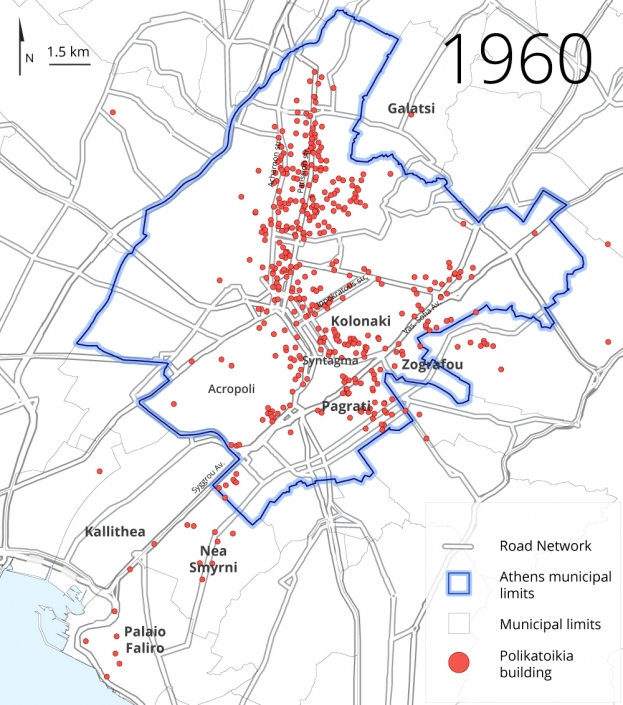

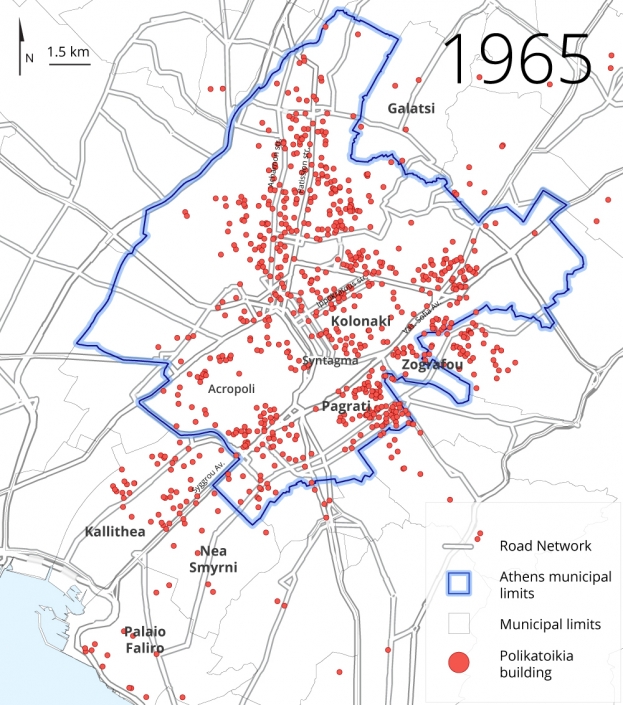

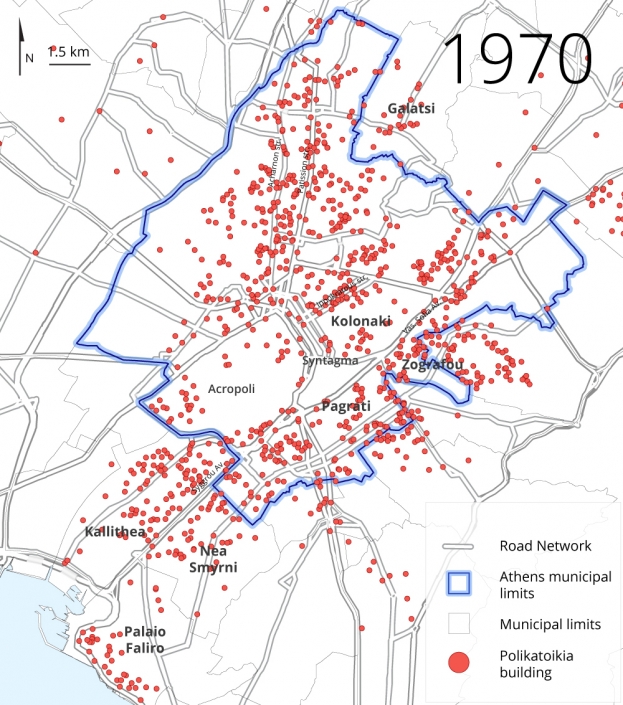

The prime repository for this research was readily available records of sanctioned building permits, published almost daily in two renowned Greek financial newspapers, Naftemporiki and Express. Our research drew upon their data pertaining to private construction activities in Athens, and its surrounding suburbs, for the years 1955, 1960, 1965 and 1970 [1] .

Photo 1 & 2: Panoramic view of Athens in 1969

Source: The digitization of the negative (film) was carried out by Babis Louizidis at the Documentation of the School of Architecture, NTUA. Reproduced with permission of Maria Romanos

While the selection of these specific years was essentially arbitrary—emerging from the observation that the first comprehensive dataset appears in 1955, and the five-year basis provides a sufficient chronological distance to capture continuities and raptures—, all four years are years of excess in terms of the construction of polykatoikia buildings (figure 1 & 2)

Figure 1: New polykatoikia buildings per year (in Athens, suburbs, and Piraeus)

Source: Comparative analysis of data from: a. Greek Statistical Yearbooks, b. the journals Naftemporiki and Express, c. Statistical Service of the Ministry of Public Works, d. the journal To Vima, 5/9/1963)

Figure 2: Percentage of polykatoikia buildings out of the total number of constructions

Source:Comparative analysis of data from: a. Greek Statistical Yearbooks, b. the journals Naftemporiki and Express, c. Statistical Service of the Ministry of Public Works, d. the journal To Vima, 5/9/1963)

Out of the total of 2,740 permits for polykatoikia buildings published in these four years, 2,712 were geospatially traceable and mapped. We recorded their publication date (typically appearing a few days after the permit issuance date), the permit holder (pertaining to either the property owner spearheading the project or the involved construction contractor), the building’s address, and the names of the architects/civil engineers endorsing the requisite plans and documents for permit authorizations. Subsequently, the signing architects and engineers were identified in registers of the Technical Chamber of Greece, and thus we also recorded their license (architect/civil engineer) and the year of obtaining it. Data related to the costs and volumes of the polykatoikia buildings were not consistently present in all published permits’ publications and were therefore left out.

Throughout the course of this research, several assumptions had to be made. First, gaps and omissions in the publication of permits were taken as random (as they were) and therefore, treated as not distorting conclusions regarding trends in proliferation, the profiles of construction firms, and so on. Second, in our macroscopic examination of polykatoikia’s sprawl within the wider region of the Attica basin—excluding Piraeus—, there was no need to exclude data lacking complete address information. When street numbers were absent (which was the case for approximately 18.5% of the total permits, amounting to 507 cases), the position was arbitrarily designated at the midpoint of the referenced street—unless alternative location indicators were provided (e.g., ‘end of Patission Avenue’). The twenty-six permits, making up 0.96% of the total, specifying only the area (e.g., Lysiatrio), were geocoded to central streets of that area, while the very few instances of street name changes that transpired from 1955 to the present were addressed through cross-referencing bibliographic sources and information available online (usually originating from citizen initiatives or various municipal authorities) [2].

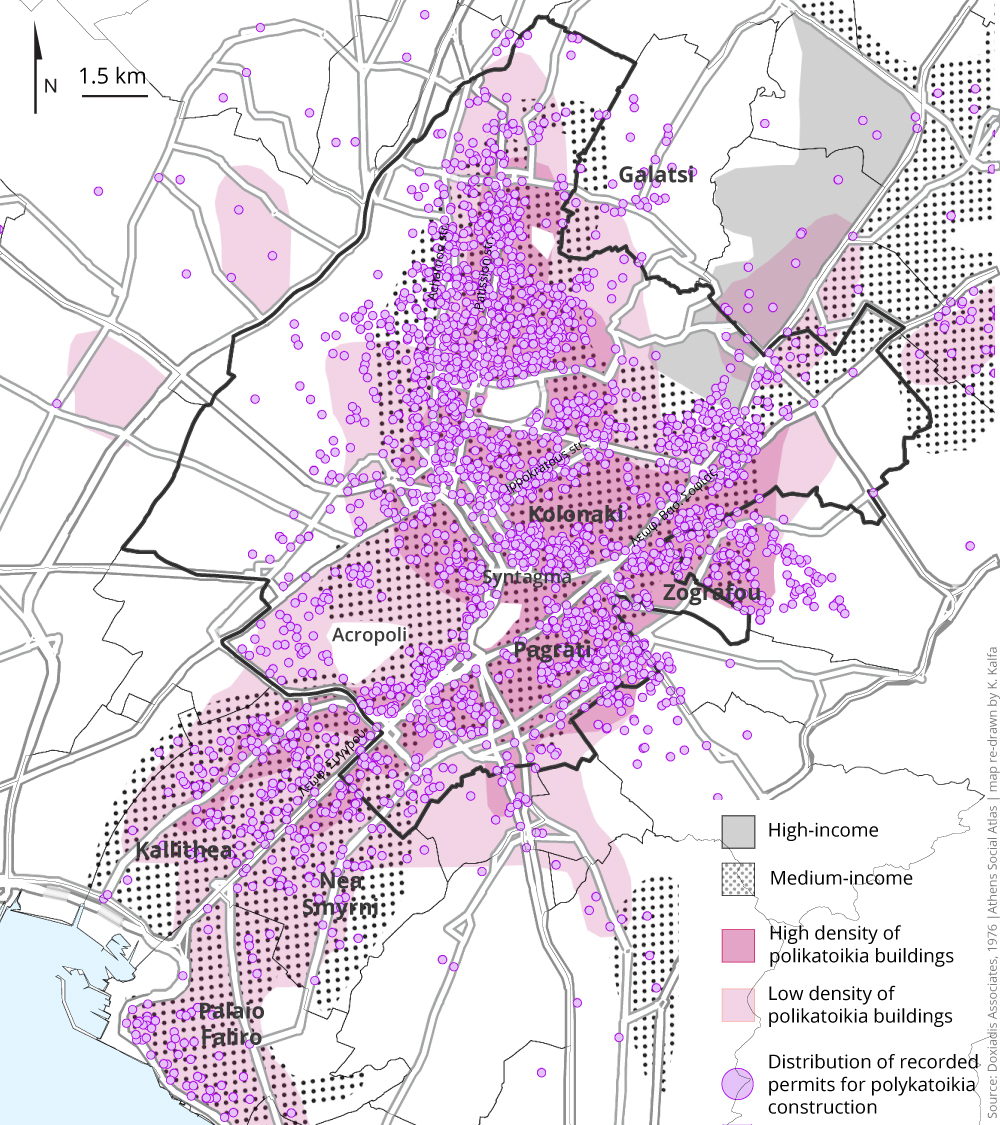

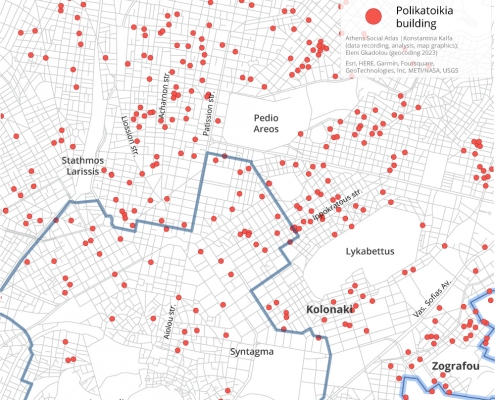

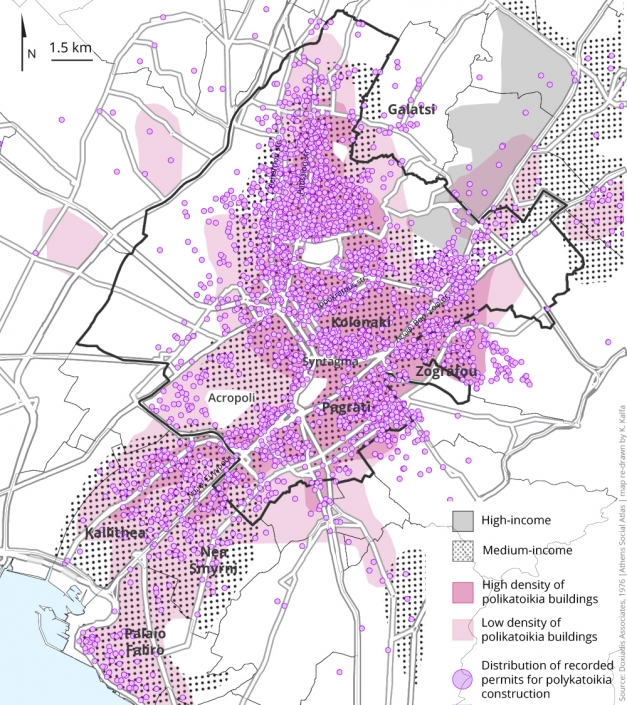

Third, we assume that building-permit data can effectively represent the actual evolution of Athens over time, even though, that is, it should be presumed that some permits may not have been realized. We held it that, as the Greek Statistical Yearbooks suggest, ‘the actual completions d[id] not usually deviate from the issued permits’ (Εθνική Στατιστική Υπηρεσία της Ελλάδας, 1954: 92). Also, as shown in Map 1, our recording of the polykatoikia buildings’ distribution agrees with what was documented in the Doxiadis Organization’s 1973 Regional Plan and Program for the Capital of Greece (Γραφείο Δοξιάδη, 1976).

Map 1: Τhe polykatoikia functions as the predominant type of housing for the era’s middle class

Source: Doxiadis Organization (Γραφείο Δοξιάδη, 1976); redrawn by Κ. Κάλφα.

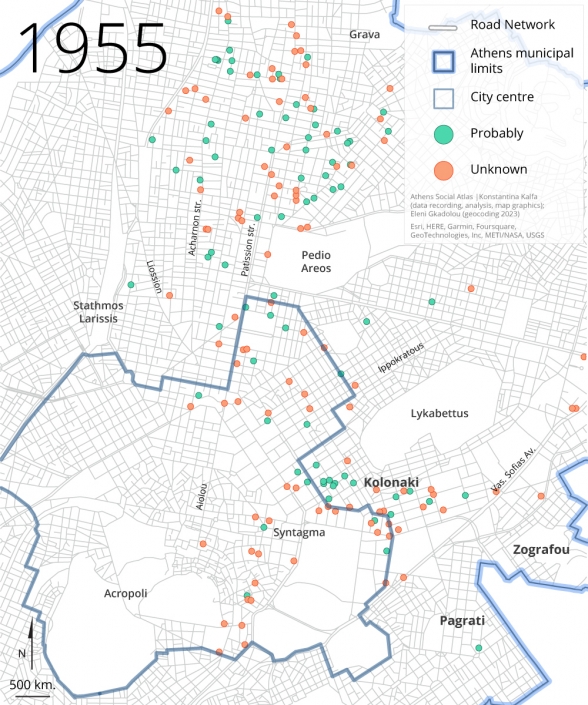

Last, we made assumptions about if a given polykatoikia was constructed through the antiparochi land-for-flats system, through research in other fields, as the ‘approved permits’ archive did not allow for definite conclusions. In particular, we cross-referenced the data generated by the archive, with oral testimonies and with findings from investigations into several construction firms’ classified ads published in the Greek Press during the period under study [3]. Based on this research we classified the records into ‘probably produced through antiparochi’ and ‘unspecified’.

Geographical spread: key findings

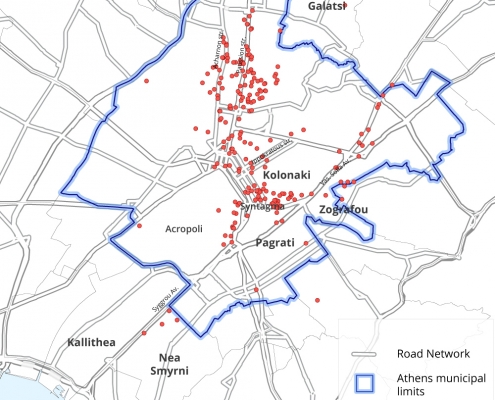

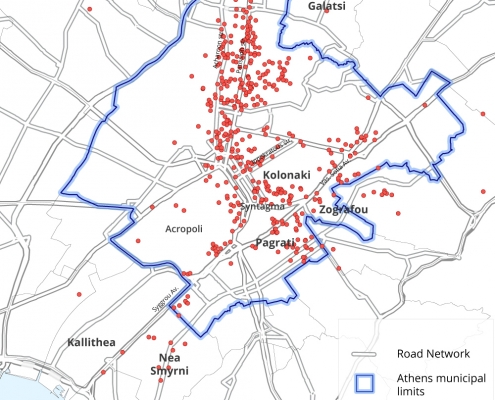

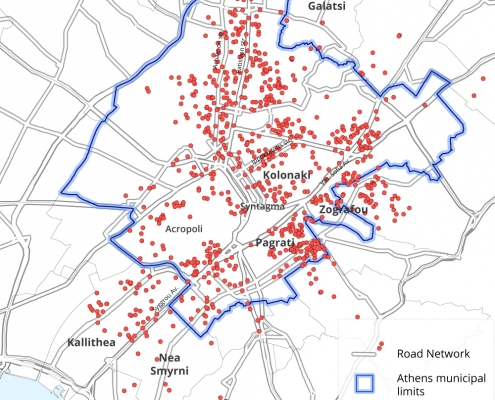

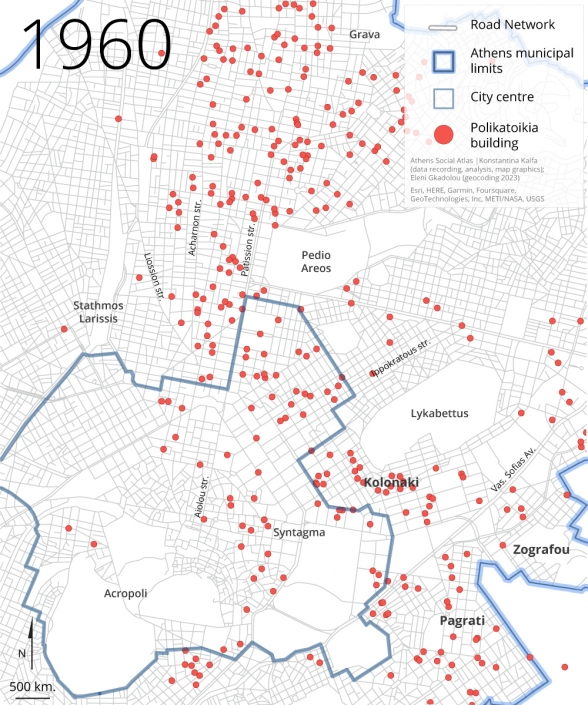

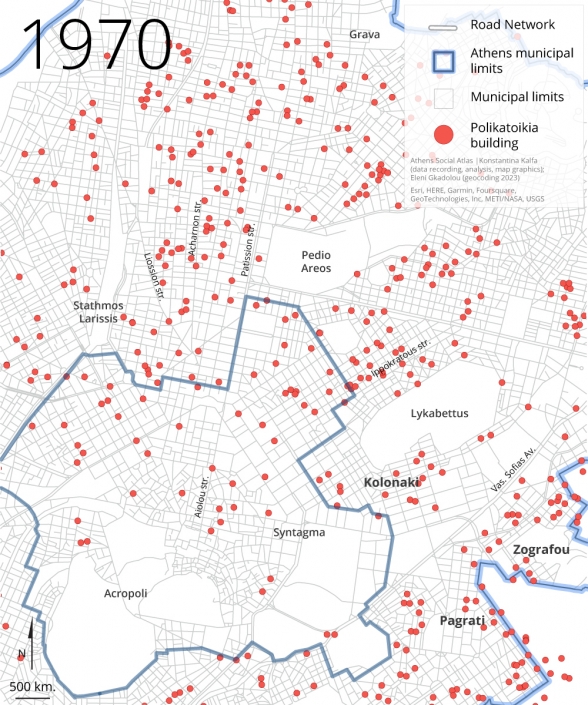

The post-war proliferation of polykatoikia buildings in Athens perpetuated pre-existing trends established during the interwar period. Their widespread presence in central and sought-after areas, particularly within the arc delineated by Marmaras (Μαρμαρας, 1991:113), encompassing Vassileos Konstantinou, Vassilisis Sofias, Panepistemiou, and Patission avenues, reflected, and further exacerbated, the socio-spatial segregation of Athens between the bourgeois eastern and the workers’ western districts—with Patission axis serving as the longstanding boundary, almost since the first plan for the city in the mid-19th century (Καρύδης, 2015) (Map 2a)

Map 2a: Geographic dispersion of all apartment building permits in Athens and suburbs (1955, 1960, 1965, 1970)

Source: Naftemporiki and Express journals

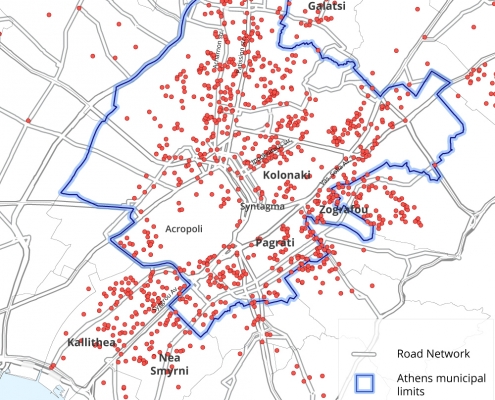

Indeed, contrary to the robust northeastern development, western development remained largely limited to the Acharnon Avenue axis, no more than half a kilometer parallel to Patission Avenue, until 1965, when a linear expansion of polykatoikia buildings emerged along Liosion Street, another half a kilometer to the west (Map 2b).

Map 2b: Geographic dispersion of all apartment building permits in the Municipality of Athens (1955, 1960, 1965, 1970)

Source: Naftemporiki and Express journals

Τhe maps have also laid visible that the growth of the polykatoikia sector was guided not only by the various small-landowners and small construction enterprises’ initiatives in free-market competition, as perhaps expected, but also by state interventions along the lines of the aforementioned uneven development, which, needless to say, formed land prices (Maps 3 & 4). Characteristically, the strategic positioning of Athens’ Hilton International and the U.S. Embassy on Vassilissis Sofias Avenue in the late 1950s and early 1960s, triggered the development of polykatoikia buildings in the neighboring areas, as both buildings functioned as symbols of the American consumerist culture and new housing standards for the middle class in the country (Wharton, 2004). These developments put an end to policies for social housing in the area, such as the planned provision of government-owned land on Ravineh Str (Hilton) for housing forty families of homeless public servants which was illegally exploited by private individuals— including Deputy Secretary of State for Housing, Emmanouil Kefalogiannis—, in 1959, through the antiparochi mechanism (Makedonia, 1961).

Map 3: Land price map for the year 1952

Source: Ministry of Public Works, Regulatory Plan for Athens, 1965

Map 4: Land price map for the year 1964

Source: Ministry of Public Works, Regulatory Plan for Athens, 1965

Development was largely linear following major avenues and central streets, a tendency driven not only by market desirability for centrality and accessibility but also by early regulations such as the 1955 General Building Regulation and the same year’s Royal Decree ‘Regarding the Terms of Construction in Athens’, (especially ΓΟΚ 1955 and Β.Δ. 30-08-1955 «Περί όρων δομήσεως εν Αθήναις», ΦΕΚ 249/Α/1955) which allowed for higher building heights along wider roads. The expansion to the south of the city’s center is a exemplary one in terms of how a freeway, Siggrou Avenue, conceived in the late-19th century as the thoroughfare connecting Athens with its wealthy seaside vacation suburbs (Faliro and Paleo Faliro), gradually fueled polykatoikia construction in all surrounding districts: starting from the southeastern side of the Acropolis rock (known as the Makrygianni district, and identified by Marmaras as an area concentrating polykatoikia buildings since the interwar period, 1991, 126), the development continued through the districts Koukaki, Kynosargos, and Neos Kosmos, and moved southward along the avenue to the suburbs Nea Smyrni, Kallithea, Tzitzifies, all the way down to the coast. The complete regeneration of entire districts like Kallithea in 1965, and Nea Smyrni in 1970, attests to these dynamics which were, nevertheless, further boosted by a set of announcements from the ruling authorities. For instance, during the July 1965 wave of protests, the dismantling of former refugee settlements was announced—a fact which could be perceived as kind of gentrification strategy, as these settlements’ residents were strong supporters of the Greek communist party (Myofa & Papadias, 2016; Λεοντίδου 2017; map 1)—, followed by several announcements for increases in building coefficients (also reflected in the 1965 Regulatory Plan of Athens, Σαρηγιάννης 2010) as well as for a host of regeneration and development projects in these districts [4].

Decisions made at the level of local municipalities were also regulating the market in an inconspicuous and yet firm manner. It is interesting to note in this respect that our research in the Urban Planning Office of Kallithea revealed that while the general regulatory framework (the 1960 Decree ‘Concerning the maximum height of buildings and the maximum exploitation coefficient of plots within the Attica basin’, ΦΕΚ 86Δ/24-6-1960), set the maximum number of floors at four, permits for 5-story buildings were issued in the years 1964 and 1965. Some of these permits even mentioned ‘5-story with provision for one additional floor.’ Although it was not possible to identify the municipal decision that allowed for such provisions, such findings suggest that private speculative initiatives in the polykatoikia construction sector could concentrate but in neighborhoods defined by favorable conditions for development, which they followed and, at the same time, shaped.

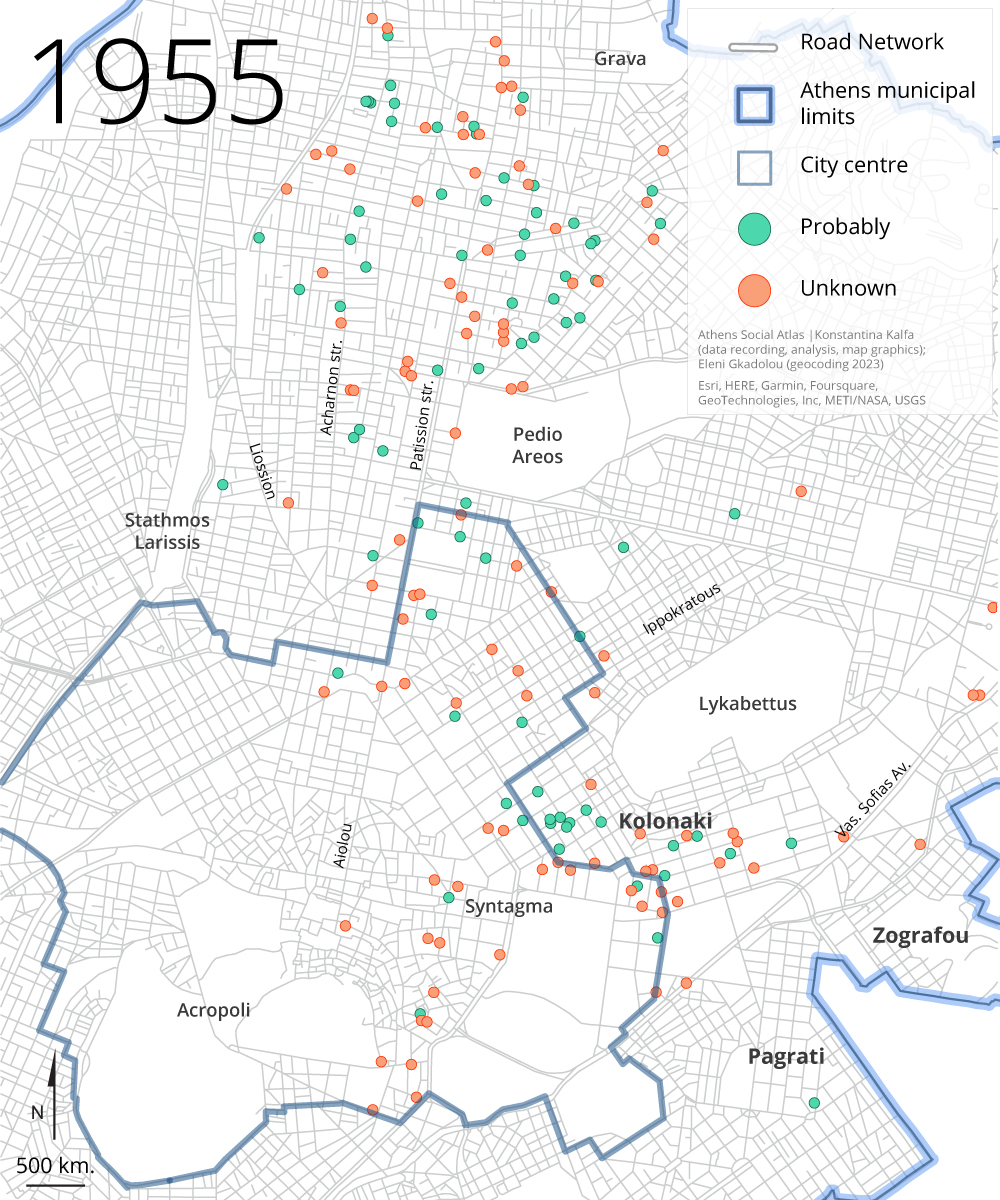

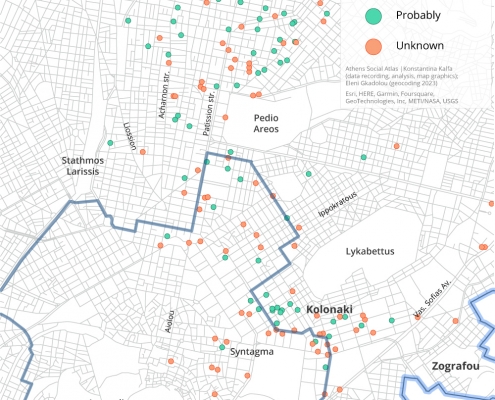

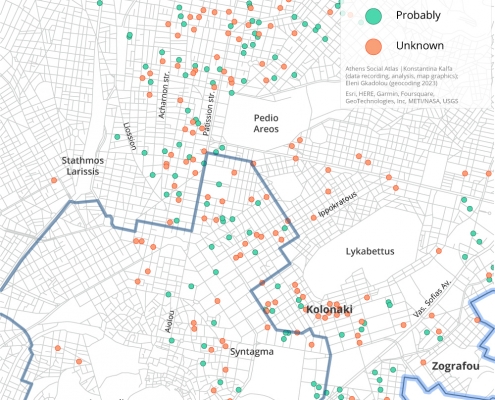

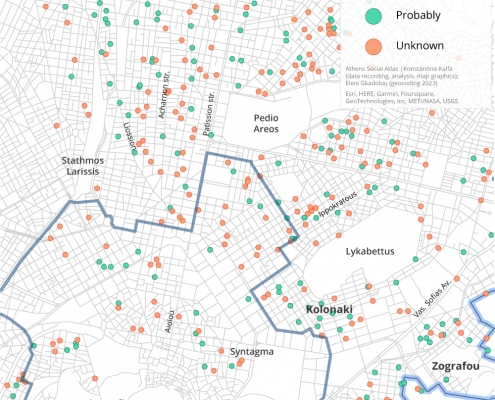

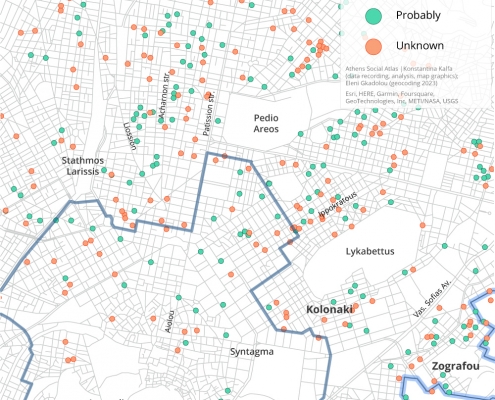

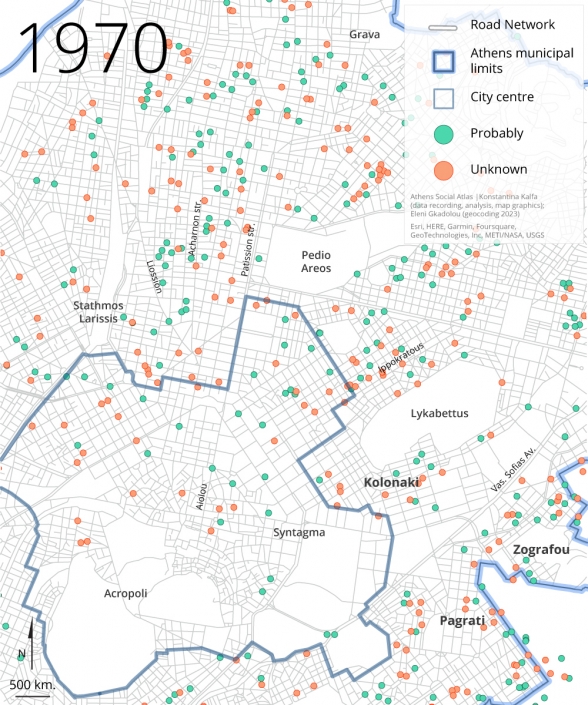

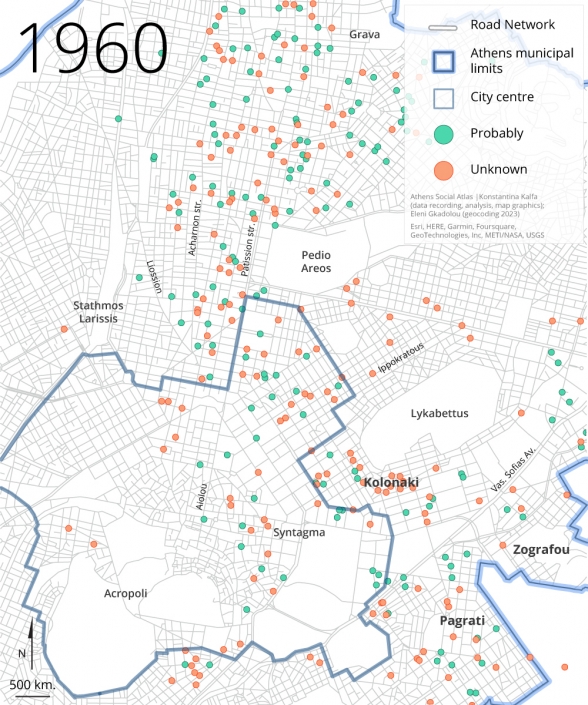

The patterns of this proliferation displayed no significant distinction in polykatoikias possibly constructed under antiparochi dealings—except for a subtle differentiation in the early years, primarily in central lower middle-class districts Amerikis Square, Kypseli, Patissia, and Ampelokipi, where antiparochi appears to have thrived more than in the more affluent districts such as Makrygianni, Kolonaki, and Kifisias Avenue (Maps 5a, 5b, 5c and Table 1). Indeed, these mappings clearly visualize the triumph of antiparochi transactions, in that they met no substantial hindrances in dealing with prime real estate, practically throughout every marketable spot in the city.

Map 5a: Polykatoikia buildings possibly constructed under antiparochi dealings and unspecified cases in the Municipality of Athens (1955, 1960, 1965, 1970)

Source: Naftemporiki and Express journals

Map 5b: Polykatoikia buildings possibly constructed under antiparochi dealings (right) and unspecified cases (left) in the Municipality of Athens (1955, 1960, 1965, 1970)

Source: Naftemporiki and Express journals

Map 5c: Polykatoikia buildings possibly constructed under antiparochi dealings (right) and unspecified cases (left) in Athens and suburbs (1955, 1960, 1965, 1970)

Source: Naftemporiki and Express journals

Table 1: Concentration of polykatoikia buildings possibly constructed under antiparochi dealings (more than ten permits) by city districts/suburbs

Source: Comparative analysis of data from: a. Greek Statistical Yearbooks, b. the journals Naftemporiki and Express, c. Statistical Service of the Ministry of Public Works, d. the journal To Vima, 5/9/1963

Key stakeholders

The archive produced yields additional conclusions that extend far beyond questions of geographical distribution. It allows us to identify the key stakeholders in the Athenian polykatoikia market on an annual basis, akin to a photographic capture, while also make assumption about their enduring involvement. Focusing in particular on the permits for polykatoikia buildings possibly produced through the system of antiparochi, which amount to 1,215 permits, thus representing 44.8% of the total 2,712 mapped permits, we conclude that these were issued by 940 construction firms. This results to an average of 1.3 polykatoikia buildings per firm for all four years, with an annual maximum 1.27 in 1960, indicating that there was no significant concentration of capital in the polykatoikia sector, at least during the 15 year-period under study, and, thus, validating theoretical assumptions on this matter [5].

Out of the 940 construction firms possibly involved in antiparochi dealings, only 194 (20%) were relatively more active, producing 2 to 5 permits over the study period (with the exception of ‘Semitelos S., Zisiadis A., and Co’ and ‘Bougiouri Brothers,’ which were even more productive with 6 and 7 permits respectively). These firms produced the 18.4% of the total polykatoikia stock (499 out of the 2,712 mapped). Annually, the percentage of the more active firms did not go beyond 23.31% of the total annual antiparochi dealings (which occurred in 1960), while the polykatoikia buildings generated by them did not surpass 18.16% of the total mapped permits (again, this was in 1960). After 1965, participation by a majority of firms with minimal production (1 permit) continued to pullulate (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Antiparochi construction firms’ activities and product

Source: Comparative analysis of data from: a. Greek Statistical Yearbooks, b. the journals Naftemporiki and Express, c. Statistical Service of the Ministry of Public Works, d. the journal To Vima, 5/9/1963

When it comes to these firms’ experience, the same motif, of fragmentation, prevails. Οnly five out of the 194 most active firms, produced polykatoikia buildings in all, or in three, out of the four years under study. Even fewer had been established long before their recorded production of polykatoikia buildings, like the firms ‘Bougiouri Brothers’ and ‘V. and Tz. Chaniotis-K. Kathreptis Technical Cooperative Company,’ identified in advertisements from the 1930s and the permits for polykatoikia buildings issued during the interwar period (2012: 240-280) [6]. The rest have followed, as a rule, a rather coincidental and opportunistic pattern of activity.

The above evidence indicates that at least throughout the study period, production and profits in the industry, as shaped by the antiparochi system, were distributed across much more entrepreneurial hands and on a much smaller scale of production per enterprise compared to the big-capital investment projects that emerged during that era in Europe and elsewhere [7].

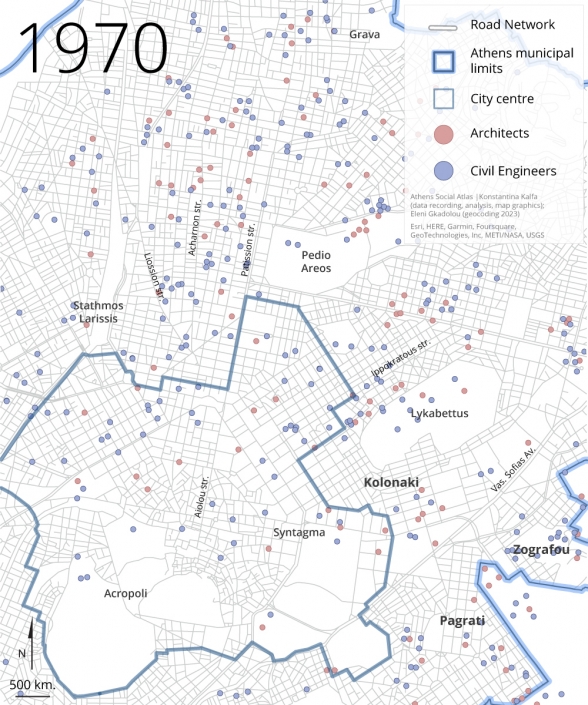

An ‘architecture’ without architects?

Regarding the training of the key stakeholders involved in antiparochi transactions, it is revealing that a significant portion (over one-third of them), had at least one shareholder with a university degree, primarily in civil engineering (accounting for five-sixths of them)[8]. They were typically the ones who signed the plans, on behalf of the firm, for the issuance of the permits. Even more telling is the fact that the ratio of the permits signed by a formal architect to the total is the same (one fourth) when considering both the permits probably produced through the system antiparochi and the total mapped permits) [9]. The same applies to the absolute number of the formal professionals signing the permits, as the ratio of civil engineers to architects equals to 3 in both the permits probably produced through the system of antiparochi and the total mapped permits) [10].

These correlations show that, for one, formal practitioners had a rather considerable share, even though a minor one, in the antiparochi sector, commonly seen as being run only by amateurish contractors who lacked any (technical) education, and secondly, that the presumed dominance of civil engineers over architects in the signing of polykatoikia building permits (primarily in those produced through the system of antiparochi) is largely a misconception. Actually, from 1945 to 1970, graduated civil engineers outnumbered architects, and hence, their greater numbers in signing the plans for polykatoikia buildings do not necessarily indicate their dominance in this sector [11]. Here, it is important to highlight that by referring to the ‘involvement’ of both architects and civil engineers, we are solely considering their signatures on the plans and other necessary documents for the issuance of the permits. In other words, we cannot account for the actual level of participation in conceiving these plans or, even more significantly, overseeing the construction process. According to Georgios Sarigiannis, in his unpublished account of the experiences of civil engineer Marinos Sarigiannis during his tenure as the head of the Structural Control Department at the Urban Planning Office of Athens and Suburbs, in the 1950s-1960s, there were instances where contractors or builders would ‘rent the professional stamp and signature of an NTUA graduate who had neither seen the plans nor knew the location of the construction» [12].

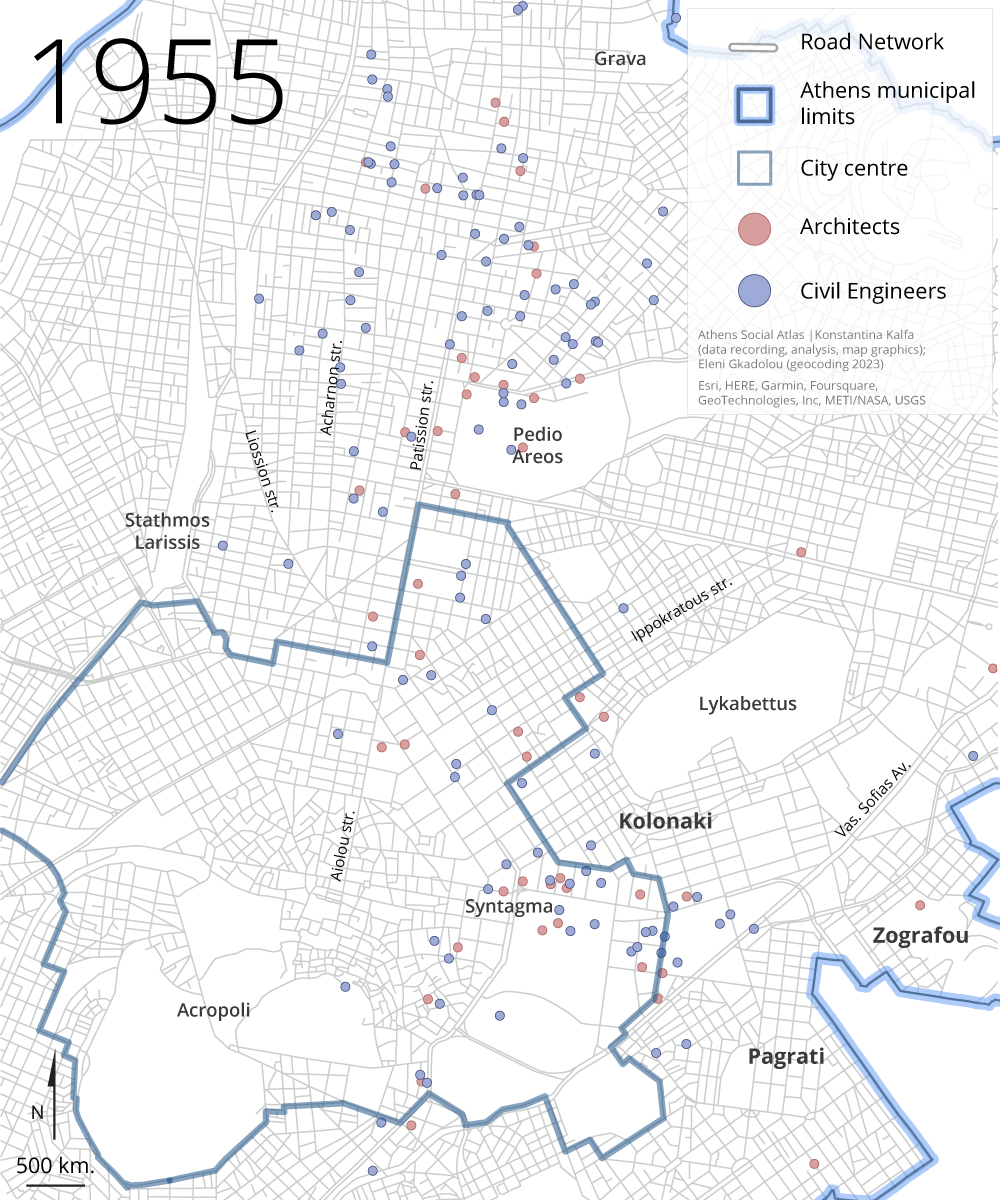

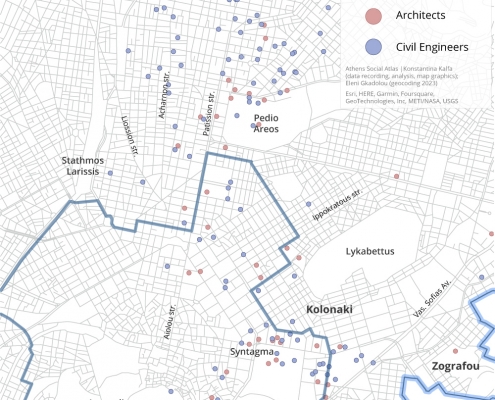

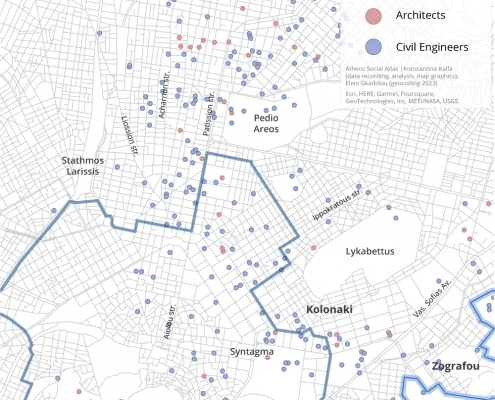

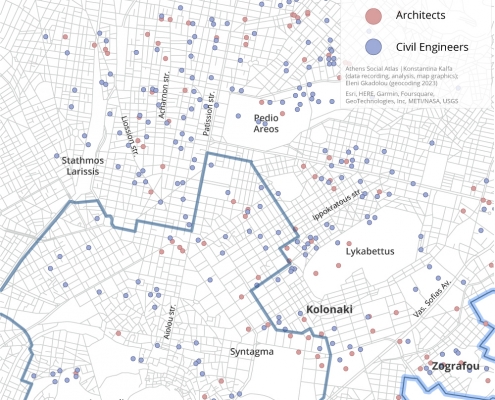

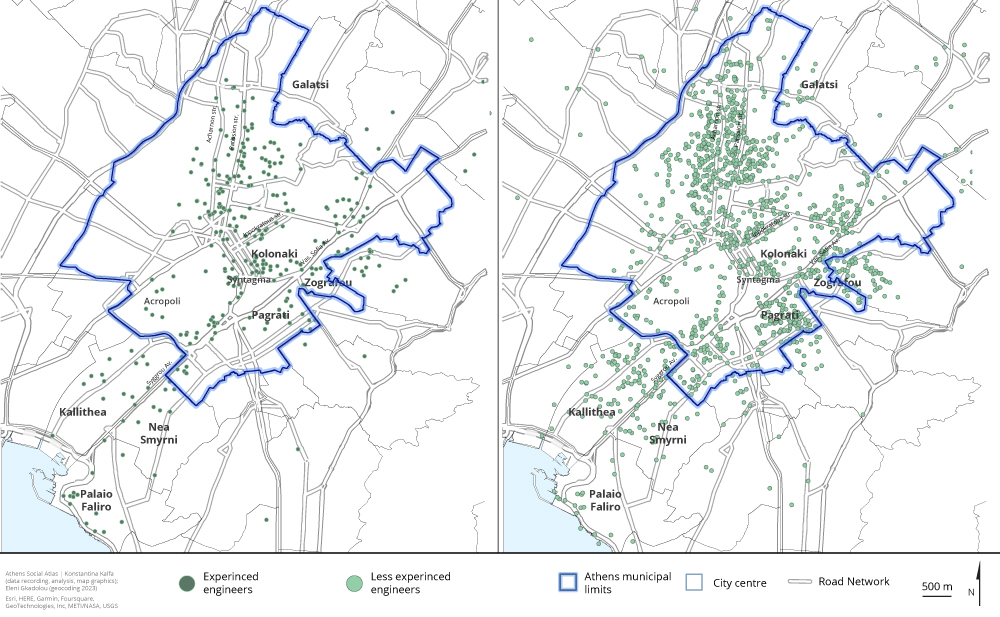

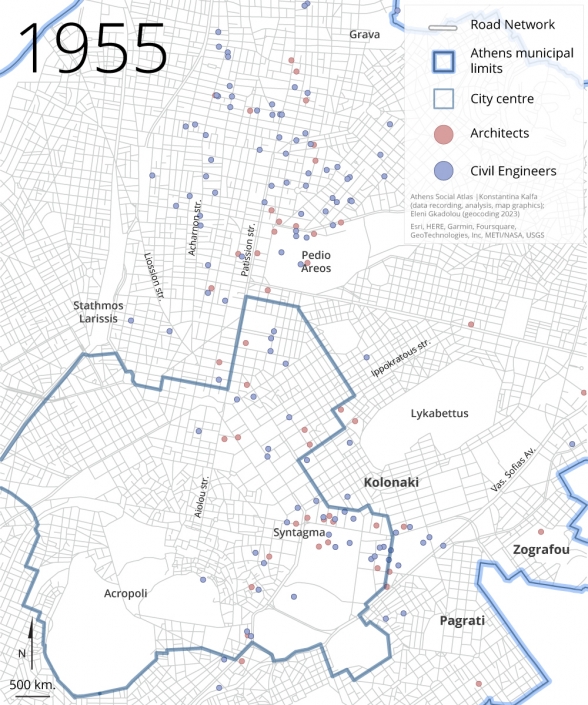

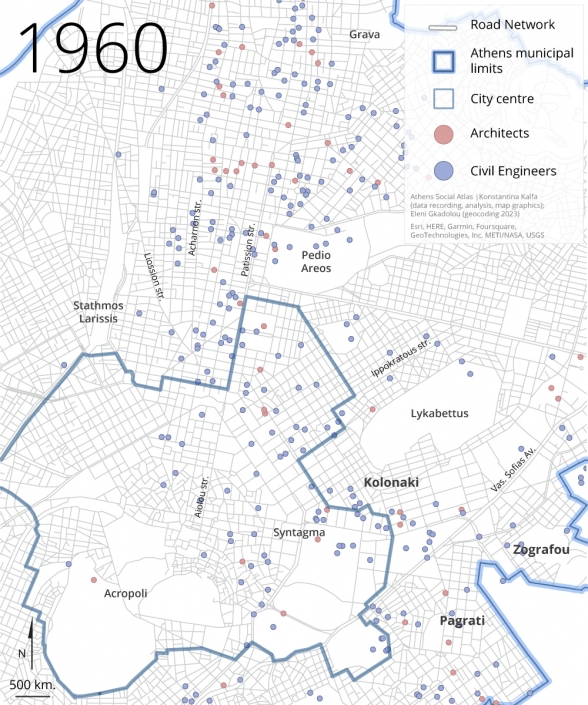

The ‘productivity’ (i.e. the number of polykatoikia permits they signed) of the two most active architects in comparison to the two most active civil engineers, is nearly identical (the top two architects signed twenty and seventeen permits, while the leading two civil engineers signed twenty-seven and seventeen permits) [13]. Therefore, the participation of architects in the permit issuance process is not inferior to that of civil engineers. Nor does any geographical pattern of dominance exist—except for a faint differentiation in 1955, where (relatively younger) civil engineers appear to have had a dominant presence in the western part of the city, primarily on Acharnon Avenue, compared to areas like Kolonaki, where more experienced architects predominated in signing permits for apartment buildings (Maps 6a και 6b).

Map 6a: Distribution of polykatoikia building permits based on who signs them (architect or civil engineer) in the Municipality of Athens (1955, 1960, 1965, 1970)

Source: Naftemporiki and Express journals

Map 6b: Distribution of polykatoikia building permits based on who signs them (architect or civil engineer) in Athens and suburbs (1955, 1960, 1965, 1970)

Source: Naftemporiki and Express journals

Regarding the experience of both architects and civil engineers, it is worth noting, parenthetically, that across all the years studied, there seems to be a distinct geographic division between two groups of engineers: the ‘experienced’ ones, who obtained their professional license 25 years ago and earlier, and the ‘inexperienced’ ones, who obtained their license within the last decade. This distinction is made by considering each year studied and counting backward in time. More precisely, it appears that experienced engineers consistently hold the advantage when it comes to issuing permits for apartment buildings in the more prestigious areas of the city (such as Kolonaki, Syntagma, or along Patission, Syggrou, Panormou avenues etc.), while the majority of less experienced engineers are active in peripheral neighborhoods and on less central streets—albeit they are not necessarily excluded from central districts and streets. Consequently, it becomes clear that the proliferation of polykatoikia buildings has been consistently directed by young, inexperienced engineers, who also happened to be the more budget-friendly workforce—a crucial criterion for any construction enterprise in this sector (Map 7).

Map 7: Geographic distribution of apartment building permits based on the years of experience of the engineer who signed them (1955, 1960, 1965, 1970)

Source: Naftemporiki and Express journals

However, despite this stratification between small, elite, groups of well-established architects (who were typically not involved in antiparochi dealings, or at least worked on polykatoikia buildings in privileged locations in the city) and the rest, architects actually played a substantial role, on par with civil engineers, in the overall polykatoikia building industry, including, that is, projects developed through the system of antiparochi [14]. Findings like these illuminate the history of not only the phenomenon of the Athenian polykatoikia and the resulting modes of urbanization—which have typically been regarded as ‘spontaneous,’ bottom-up products, ‘designed by non-architects and engineers’ (as posited by esteemed scholars like Kenneth Frampton; Frampton in Theocharopoulou, 2022:7)—, but also of the architectural profession in Greece. They in fact deepen our understanding of Greek architecture’s alleged ‘failure’ to leave its mark on the country’s built environment. As discussed elsewhere (Kalfa 2022; Kalfa and Theodosis 2022), the success of antiparochi was contingent upon specific criteria that molded polykatoikia into a commonplace building type, subjugating any ‘will to’ architecture to the rules of an idiosyncratic market, while at the same time allowing Greek technicians to enjoy the advantage of capitalizing on the construction boom within the country.

‘Neighborhood contractors’ and other strategies

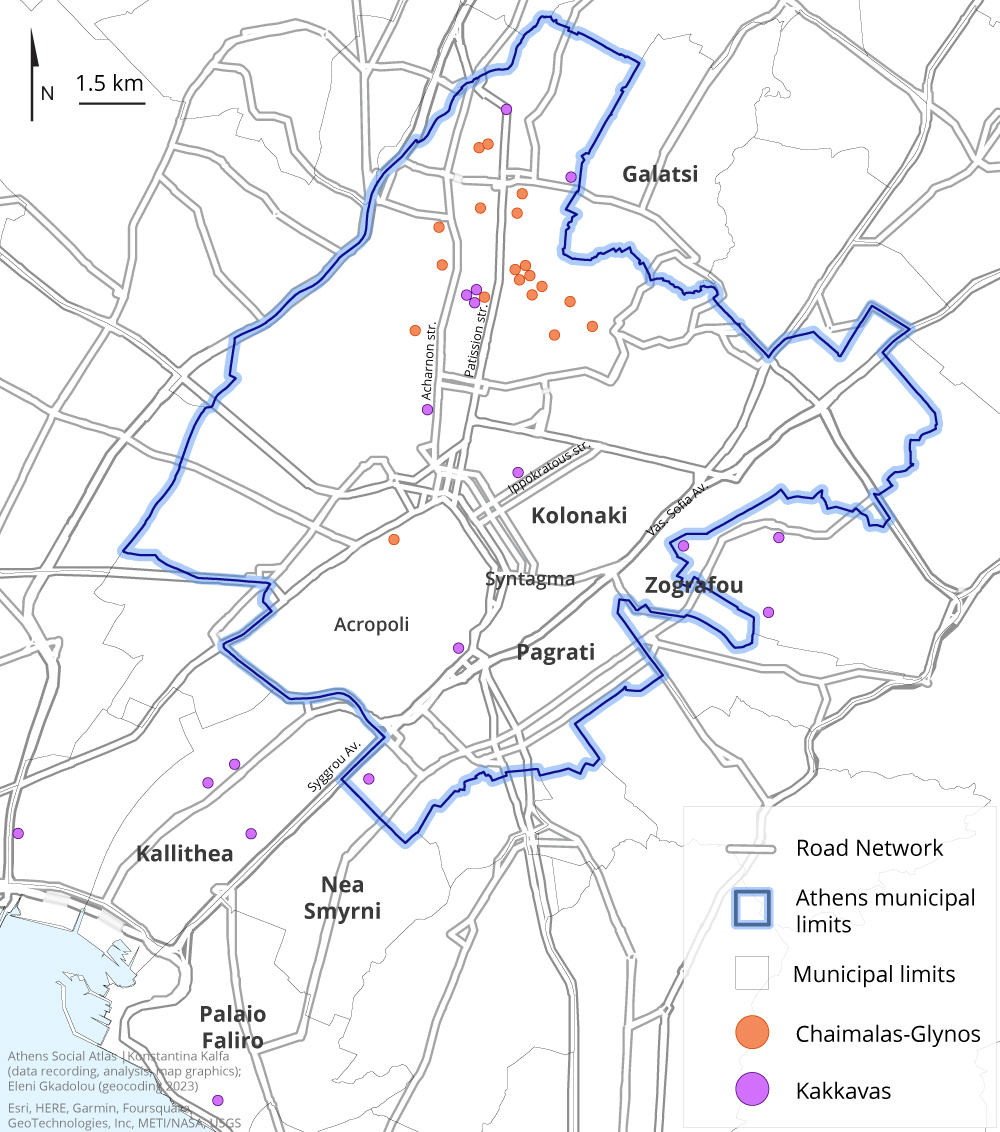

The geographic dispersion of each construction firm’s output further validates that the Athenian real estate market, shaped by antiparochi, accommodated various, at times conflicting, strategies. Although we did not yet proceed on a comprehensive quantitative study to firmly conclude on whether the dominant pattern is for the various firms’ product to cover the entire area of polykatoikia buildings’ dispersion in a given year or if antiparochi contractors operated locally as ‘neighborhood contractors’ (that is, being active in specific districts through a network of personal contacts, often using local cafes as their offices, as explained by Maria Mantouvalou in Alifragkis and Kalfa 2021), we are confident that both models were in operation. For example, the two successful companies mentioned earlier, ‘Bougiouri Brothers’ and ‘V. and Tz. Chaniotis-K. Kathreptis Technical Cooperative Company’ operated as ‘neighborhood contractors’: between 1931 and 1970, the geographic dispersion of polykatoikia buildings for both of these firms was limited from Omonoia Square to Koliatsou Square in the north-south direction and from Karaiskaki Square to Kanari Square in the east-west direction [15]. On the flip side, other equally successful contractors constructed buildings across an impressive geographical range from the northern suburbs to the southern ones. A typical case is Dimosthenis Kakkavas, a renowned contractor deep into the antiparochi scene [16].

Examining Kakkavas’s business in comparison to yet another successful construction firm engaged in antiparochi dealings during the same period, the ‘Construction and Real Estate company Chaimalas-Glynos,’ none of whom were registered engineers and possibly lacked any formal training, we can reach certain preliminary, and yet intriguing conclusions [17]. Between 1965 and 1971, Kakkavas produced at least twenty polykatoikia buildings, scattered all over Attica, while Chaimalas-Glynos’ activity was limited to the northeastern districts of Athens (Patissia-Kypseli-Agios Eleftherios) (Map 8) [18].

Map 8: Geographic dispersion of polykatoikia buildings produced by Dimosthenis Kakkavas and Chaimals-Glynos in Athens and suburbs

Source: Naftemporiki and Express journals

And yet, despite these diverging strategies between the two, no recognizable differences in their product are observed, besides the fact that Chaimalas-Glynos’ buildings are generally smaller in volume. Once again, we are led to conclude that the polykatoikia building type is less the product of individual stylistic preferences than it is of the ‘laws’ of speculation, even if those were prescribed in each era’s market trends and tastes and the current regulation (the General Building Code) (in this case: penthouses on the final floors, the so-called ‘artificial’ technique in the plastering, colorations in shades of beige and ochre, typically long balconies with simple metal railings, glass panels between different apartments’ balconies, and awnings in green, blue or orange).

Closing remarks

The unglamorous and incredibly labor-intensive task of digging building permits data for anonymous commercial apartment buildings falls entirely outside the established or even state-of-the-art methods of architectural and urban history. Nevertheless, mapping such data promises shifts in how we understand architecture as a cultural practice. As we emphasized at the outset, this publication presents only an initial set of findings that begin to unveil the ‘anonymity’ of contemporary, apartmentalized, Athens to some extent. New computational tools could analyze architectural traits within large datasets and ‘recognize’ their key factors and agents —ownership, legislative framework, spatial policies, entrepreneurial initiatives, land market, and so on. Overall, the effort herein, by shedding light on the bonds between ‘improvised’ home- and city-making practices, political economy, and top-down decision making, can raise questions not limited to Athens only, but also relevant to any context where housing and the production of the built environment were not undertaken by centralized mechanisms or promoted by the welfare state, and even, offer back insights that may be applicable to Western organized planning contexts (Kalfa, Alifragkis και Tournikiotis, 2022).

Acknowledgments

Part of the research presented here was conducted within the framework of the three-year research program ARCHIPAROCHI (PI: K. Kalfa), funded by the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (HFRI) and the General Secretariat for Research and Technology (GSRT), under grant agreement No 1693. We extend warm thanks to Kyriakos Gklezakos and Georgios Sarigiannis for their valuable insights shared during our discussions. We also appreciate the encouragement of Thomas Maloutas to publish this work and the ongoing collaboration and critical advice of Stavros Nikiforos Spyrellis, as well as his technical support.

[1] Data recording and analysis were conducted by Konstantina Kalfa. Geocoding was performed by Eleni Gkadolou.

[2] See for instance: https://www.alimosonline.gr/αναμνήσεις/30027-Λίστα%20οδών%20και%20πλατειών%20που%20άλλαξαν%20στο%20παρελθόν%20ονομασία%20στον%20Άλιμο-1.

[3] Interviews were conducted using oral history methods by Konstantina Kalfa and Stavros Alifragkis between February 2019 and February 2020 (a small selection of them included in the short documentary ‘Antiparochi – A Short Introduction,’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dvjFiopD9wA). Research on classified ads was conducted by Emilia Athanassiou. Both tasks were part of the Research Program ‘Antiparochì and (its) Architects: Histories of Social Forces, Spatial Politics and the Architectural Profession in Greece, 1929-74’ (ARCHIPAROCHI, 2018-2022) (PI: Konstantina Kalfa). Discussions with researcher Kyriakos Gklezakos also helped a lot in this inquiry.

[4] See, for example, ‘Faliro’s coast will be transformed into a cosmopolitan center,’ To Vima, February 9, 1967, p. 4; ‘The largest Greek square in Nea Smyrni,’ To Vima, January 19, 1969, p. 4; ‘In Nea Smyrni, floors are increasing by one in all cases,’ To Vima, Tuesday, July 14, 1970, p. 8.

[5] The yearly averages polykatoikia buildings/firm are: 1.17 in 1955, 1.27 in 1960, 1.2 in 1965, and 1.19 in 1970. Also: Interview with the economist Ilias Katsikas in the context of the Research Program ARCHIPAROCHI, February 2019.

[6] N. and I. Bougiouris constructed two polykatoikia buildings (in 1935 and 1937), and B. Chaniotis built four (in 1931, 1939, 1940, and 1941). It is noted that through a random sampling of ‘plot wanted’ advertisements, the ‘Chaniotis-Kathreptis’ company was found in five advertisements (at the journal Eleftheria on March 5, 10, and 14, 1964 and To Vima on July 5 and August 15 1964), seeking plots in the areas of Patissia, Kypseli, and Acharnes, for exchange on antiparochi.

[7] As additional support for this conclusion, a random sampling of classified ads in the Greek daily press revealed yet another sixteen construction companies engaged in polykatoikia building projects. Although they did not have any projects during the four years under examination (and were thus not initially discovered in our research), these companies exhibited substantial activity during the study period (e.g. the ‘Credit Building Organization Mich. Papailias-Chr. Moschandreas and Co.’ and the ‘Construction Companies of Georgios Sakketos’).

[8] Conclusions cannot be drawn for nine of the remaining companies.

[9] One hundred fifty-six permits out of the total mapped have been signed by ‘engineers’ who could not be identified in the records of the Technical Chamber of Greece.

[10] A total of 1,334 engineers (both architects and civil engineers) signed the 2,712 mapped permits. It is also worth noting that the ratio of all engineers in the total number of permits to the engineers who signed the potential antiparochi permits is the same, both for architects and civil engineers (1.9).

[11] Up until 1967, civil engineering students accounted for one-third of the total student population across all other departments of the National Technical University of Athens. See . http://www.civil.ntua.gr/info/history/ and Σαρηγιάννης, 1977: 64-91.

[12] We thank Georgios Sarigiannis for kindly allowing us to publish this information

[13] The second most active civil engineer, Charalambos Vovos (born in 1934, graduated in 1957) with 12 permits for potential antiparochi, is the well-known founder of ‘Babis Vovos Hellenic Tourist S.A.’ (1974), renamed to ‘Babis Vovos – International Technical S.A.’ in August 1999 (http://www.babisvovos.gr/home.asp?pg=glance, https://el.wikipedia.org/wiki/Μπάμπης_Βωβός).

[14] Recent research revealed that even well-known architects like Constantinos Doxiadis and Suzanna and Dimitris Antonakakis were indeed deeply involved, for different reasons and in different ways, in antiparochi construction (Kalfa and Alifragkis 2022, Kalfa and Theodosis 2022). Besides, the building permits we studied were signed, among others, by some of the era’s most famous architects.

[15] Based on our research in building permits and classified ads.

[16] It is noteworthy that Doxiadis Organization construction company ‘Zygos S.A.’, which constructed polykatoikia buildings through the antiparochi system, ‘spied’ on the Kakkavas’s enterprises in early December 1970 (Kalfa and Theodosis 2022).

[17] The fact that ‘Chaimalas-Glynos’ were involved in antiparochi transactions in the areas of Kypseli, and Patission and Acharnon avenues is confirmed by relevant advertisements in the newspaper To Vima (see, for example: November 27, 1964, February 18, 1965, June 14, and December 31, 1967)

[18] For the study of these two cases, additional information was also sought from advertisements and promotions of the two firms, especially from the newspapers To Vima, Macedonia, Oikonomikos Tachydromos, and Eleftheros Kosmos.

Entry citation

Kalfa, K. (2023) Athens apartmentalized, 1955-1970, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/athens-apartmentalized-1955-1970/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.116

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Allweil, Y (2017) Homeland: Zionism as housing regime, 1860-2011. Νέα Υόρκη: Routledge.

- Alweill, Y (2022) Housing as architecture history of quantity. Στο EAHN22 Στρογγυλή Τράπεζα Housing History as a Methodological Observatory. Μαδρίτη, 15-18 Ιουνίου.

- Γραφείο Δοξιάδη (1976), Χωροταξικό Σχέδιο και Πρόγραμμα Περιοχής Πρωτευούσης, Τελικη Εκθεση, τ.Ι και ΙΙ. Αθήνα.

- Caramellino, G και De Pieri F (2019) Private generalizations: The Emergence of the micro scale in historical research on modern housing. Στο: Kockelkorn, A και Zschocke Ν (επιμ.) Productive Universals/Specific Situations: Critical Engagements in Art, Architecture and Urbanism. Βερολίνο: Sternberg Press, σ. 294-315.

- De Pieri, F, et al. (επιμ.) (2013) Storie di case. Abitare l’Italia del boom. Ρώμη: Donzelli.

- ΕΣΥΕ (1954) Συνοπτική Στατιστική Επετηρίς της Ελλάδος. Αθήνα: Εθνικό Τυπογραφείο.

- Frampton, K (2009) Μοντέρνα Αρχιτεκτονική. Ιστορία και κριτική. Αθήνα: Θεμέλιο, 2009.

- Kalfa, K και Alifragkis, S (2022) Atelier66 and the Athenian polykatoikìa: Power, control and agency agendas in and the 1960s-1980s Greek commercialised housing market. Στο: Editorial seminar Housing histories as a methodological observatory. Μιλάνο, 10-11 Νοεμβρίου.

- Kalfa, Κ και Theodosis, L (2022) Dealing with the Commonplace: Constantinos A. Doxiadis and the Zygos Technical Company. ABE Journal 20, http://journals.openedition.org/abe/13699.

- Καλογερόπουλος, Κ, Τσάτσαρης Α, Χαλκιάς Χ (2018) Μελέτη αστικής επέκτασης μέσω ιστορικών χαρτογραφικών τεκμηρίων – Η περίπτωση της Πετρούπολης. Στο Μαλούτας Θ., Σπυρέλλης Σ. (επιμ.) Κοινωνικός άτλαντας της Αθήνας, https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/άρθρο/η-αστική-επέκταση-της-πετρούπολης/.

- Καρύδης Δ. (2015) Αθήνα: Κοινωνική διαίρεση του χώρου στο πέρασμα από την πόλη των Οθωμανικών χρόνων στην ελληνική πρωτεύουσα, στο Μαλούτας Θ., Σπυρέλλης Σ. (επιμ.) Κοινωνικός άτλαντας της Αθήνας. Ηλεκτρονική συλλογή κειμένων και εποπτικού υλικού (https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/άρθρο/απαρχές-κοινωνικής-διαίρεσης/).

- Λεοντίδου Λ (2017) Φτωχογειτονιές της ελπίδας, στο Μαλούτας Θ., Σπυρέλλης Σ. (επιμ.) Κοινωνικός άτλαντας της Αθήνας. Ηλεκτρονική συλλογή κειμένων και εποπτικού υλικού (https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/άρθρο/φτωχογειτονιές-της-ελπίδας/).

- Μαρμαράς, Μ (1991) Η αστική πολυκατοικία της μεσοπολεμικής Αθήνας: Η αρχή της εντατικής εκμετάλλευσης του αστικού εδάφους. Αθήνα: Πολιτιστικό Ίδρυμα Ομίλου Πειραιώς.

- Μαρμαράς, Μ (2012) Για την αρχιτεκτονική και την πολεοδομία της Αθήνας: Δεκατέσσερα κείμενα και ένα αρχείο. Αθήνα: Παπαζήσης.

- Μelsens, S, et al. (2022) Intermingled Interests: Social Housing, Speculative Building, and Architectural Practice in 1970s and 1980s Pune (India). ABE Journal 20, http://journals.openedition.org/abe/13394

- Μυωφά Ν, Παπαδιάς Ε (2016) Η εξέλιξη της γειτονιάς Δουργούτι στο Νέο Κόσμο από το 1922 έως σήμερα, στο Μαλούτας Θ., Σπυρέλλης Σ. (επιμ.) Κοινωνικός άτλαντας της Αθήνας. Ηλεκτρονική συλλογή κειμένων και εποπτικού υλικού (https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/άρθρο/δουργούτι/#4).

- Paschou, Α (2008) Urban block in post-war Athens development, form and social context. Διδακτορική διατριβή, ETH Zυρίχης.

- Σαρηγιάννης, Γ (1977) Η αρχιτεκτονική στην Ελλάδα και οι σπουδές της στο ΕΜΠ, Τεχνικά Χρονικά 3: 17β, 64-91.

- Σαρηγιάννης, Γ (2010) Τα ρυθμιστικά σχέδια Αθηνών και οι μεταβολές των πλαισίων τους, Greekarchitects, διαθέσιμο στο: http://www.greekarchitects.gr/gr/αρχιτεκτονικες-ματιες/τα-ρυθμιστικά-σχέδια-αθηνών-και-οι-μεταβολές-των-πλαισίων-τους-id3464.

- Wharton A J (2004) Building the Cold War: Hilton International Hotels and Modern Architecture, University of Chicago Press, pp. 41-70.

- Woditsch, R (επιμ.) (2018) The public private house: Modern Athens and its polykatoikia. Ζυρίχη: Park Books.

Υπουργείον Δημοσίων Εργων, Υπηρεσία Οικισμού, Ρυθμιστικόν Σχέδιον Αθηνών, Αθήναι 1965

Websites:

- Αθήνα – Βικιπαίδεια (wikipedia.org)

- http://www.civil.ntua.gr/info/history/

- «Antiparochi – A Short Introduction», https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dvjFiopD9wA.

- https://www.alimosonline.gr/αναμνήσεις/30027-Λίστα%20οδών%20και%20πλατειών%20που%20άλλαξαν%20στο%20παρελθόν%20ονομασία%20στον%20Άλιμο-1.

Journals:

- Ελευθερία

- Το Βήμα

- Μακεδονία

- Οικονομικός Ταχυδρόμος

- Ελεύθερος Κόσμος