2015 | Dec

Starting in late 2009, the new Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change (YPEKA) with its departments and supervising organisations, intensively crafted the first integrated framework to address sustainably critical issues of the city and the metropolitan area. The “ATHENS-ATTICA 2014 Project”, as it was named, was published in magazine format (figure 1) and presented in June 2010. The name did not intend to have a reference with regards to its completeness, but was a symbol of a missed opportunity at city level: 10 years after the Olympic Games, it was imperative to proceed with the needed spatial, developmental and environmental changes which were not implemented following the completion of the games.

Figure 1: Cover of the YPEKA Issue “ATHENS-ATTICA 2014”

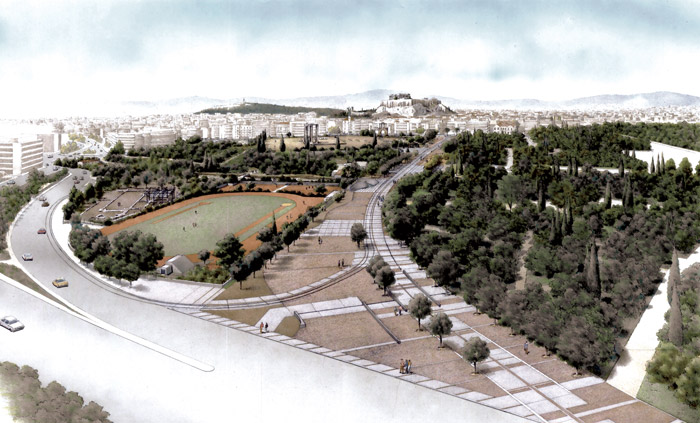

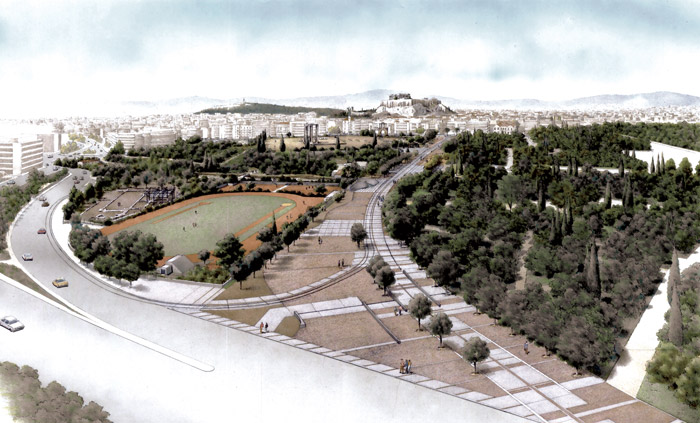

The Project reflected an integration of various visions, and proposed a set of strategic actions for Athens and Attica. Major projects were also included, such as the intervention along the emblematic axis of Panepistimiou Street -as a key strategy to re-program mobility in the city centre, or the creation of the already planned but seriously delayed Metropolitan Park at Faliron Bay, and the partial pedestrianization of Vasilissis Olgas Avenue (figure 2) which would complete the large central archaeological promenade.

Figure 2: Rehabilitation of Vasilissis Olgas Avenue

At the dawn of crisis, it was already understood that the city needed to adapt to a changing world and the importance of planning while taking into account new types of synergies and procedures, was stressed. The project’s main objectives were the sustainable development balancing production and ecology, the promotion of an awareness about how we move in the city and how we perceive it, the rehabilitation of lagging areas with degraded building stock, the modern day definition of an image for the metropolis, and the conservation of its natural and cultural wealth. The work comprises the priorities, methodology and mechanisms, and reveals the set targets for the new Athens and Attica Regulatory Plan.

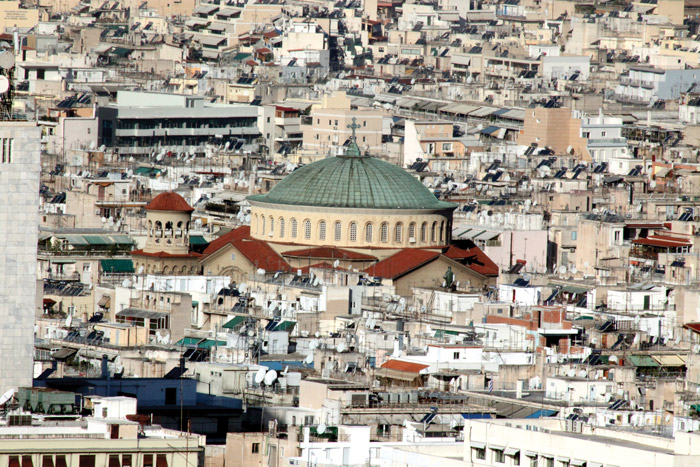

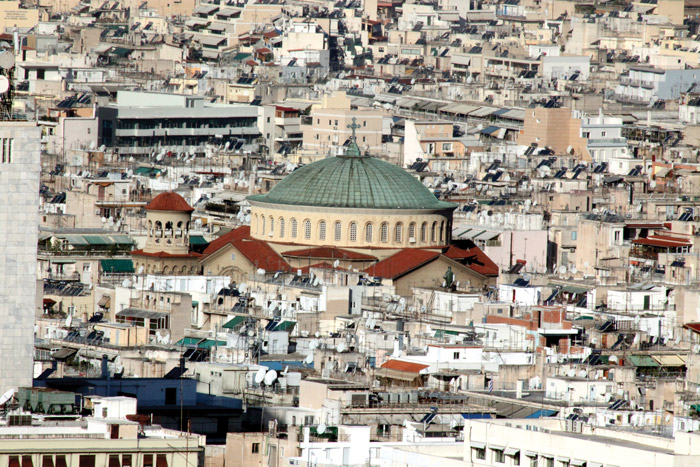

The structure of its four chapters reveals the new logic ruling the project. The first chapter, “Improving the City’s Functions and Image”, records emblematic and other smaller projects, several of which have been launched. Many issues, such as seeking methods to upgrade Pireos Street, were incorporated in a research project appointed to the National Technical University of Athens (NTUA), the outcome of which provided the basic information for the architectural competition regarding the intervention along Panepistimiou Street. The research project also analysed the double pole of the city centres of Athens and Piraeus and their dynamic relation. After years of not producing design work, the Ministry prepared through the Direction of Special Projects for Local Improvement (DEEAP) studies for such interventions as Ag. Panteleimon Sq. and Agorakritou street (figure 3), Attikis Sq. and Ag. Nikolaos Sq., and the preliminary study for the regeneration of the area comprising the old Refugee Buildings in Kaisariani. The same chapter includes an upgrading or reconstruction by adopting new approaches of various city regions, and a pilot study conducted by the SARCHA group for the Gerani area of the degraded Center; also the large metropolitan project of the former airport at Elliniko emphasising the creation of a Metropolitan Park, the Port and industrial zone of Drapetsona-Keratsini, Eleonas, and the Metropolitan Parks of Goudi and “A. Tritsis”. Finally, the work highlights the need for legal-institutional arrangements, policies and financial tools that are necessary for the implementation of the above.

Figure 3: Ag. Panteleimonas Square

The second chapter, “Sustainable Urban Mobility in Attica” raised the urgent issue of how to change our attitudes in moving and perceiving the city in new terms (figure 4). The third chapter, “Protection and sustainable management of the countryside and the mountains of Attica” stressed the need to protect the natural environment (figure 5) and limit sprawl to regions outside the city plan, which was later confirmed by the proposals set by a new Regulatory Plan. Finally, the 4th chapter, “Sustainable management of the coastal zone of Attica” prioritises the opening of the city to the Saronic Gulf and the rest of the coastal area. The lack of green spaces in Athens is balanced by the presence of many coasts inside its urban fabric, which add value as open spaces. The work lists a number of terms and conditions for addressing informal structures and other problems, and ends with a list of key actions, many of which were planned but never implemented.

Figure 4: Traffic problems and the need for sustainable mobility

Figure 5: Parnitha Mountain on fire: the destruction of natural resources

The investment in the new Athens-Attica Regulatory Plan (ARP) was extensive and supported a spatial development respectful of the environment, promoting integrated rehabilitation policies for the existing urban fabric (figure 6). The new ARP would seek to halt urban sprawl in peri-urban space, particularly in North and East Attica, to provide incentives for the relocation of production activities of high-disturbance in organised existing or new industry receptors, and a sustainable transport system for passengers and goods, giving priority to fixed course public transport, walking and cycling.

Figure 6: Cover of the YPEKA Issue with the proposal of the new AMP

As sufficient time has passed since the publication of the work, we can objectively assess its strengths and weaknesses. Comparing it with current approaches to solving the same problems, we can perceive it as penetrating, visionary and bold, given the realities it had to address. The new ARP specifically aimed to be a key redesign tool for the long-term sustainable development of Attica. Regarding the complicated issues of the Center, the work from its outset considered that a poor image of public space and its appropriation have a negative impact on social behaviour, and formulate devaluing standards for collective existence. It also stressed the need for participatory processes to upgrade lagging regions with apparent marginalisation; it clearly understood that the regeneration of the abandoned Center is associated with tolerance for people who live under unacceptable conditions, and dealing with their problems in a positive way is a condition for its sustainable social and economic function. The need for joint action by the central and local governments and civil society, in addressing complex problems related to diversity and the exclusion of vulnerable groups, was highlighted (figure 7).

Figure 7: Immigrants in the Center

Today, years after the launch of the program, a humane management of the various immigrant groups of the city has not been achieved, although these people could contribute covering deficient welfare services, providing a margin for survival to many small businesses.

Given its location, geometry, architecture, history, urban planning and economic importance, and its significance for the public transport and tram network, Panepistimiou Street was selected as the spine of interventions to regenerate the Center and as a most important axis to be offered to pedestrians and the enjoyment of the city. The implementation of this plan is still being pursued. Unfortunately, despite the amendment of its original scope in order to comprise urban upgrading, the annulment – instead of upgrading- of EAXA S.A. does not contribute to the efficient implementation of the program’s historical, aesthetic and functional activities.

The Project ATHENS-ATTICA 2014 led to architectural tenders which were held within a new institutional framework, and fed the public debate on urban architecture and culture. In addition to the competition for Panepistimiou Street, the program promoted tenders undertaken by EAXA S.A. for the regeneration of Theatrou Sq. and ATHENSX4 (regarding the recovery and reallocation of public space, enhancing its image and green) and for the landmark building (undertaken by DEEAP) at the end platform of a pier at Faliro Bay’s metropolitan park. Finally, in collaboration with the School of Fine Arts, three large scale emblematic wall paintings were applied on building façades, creating unexpected encounters of the city’s residents with art, at a time when citizens were inactive, public space had become confined or commercialised, and the role of art was crucial (figure 8).

Figure 8: Wall painting on a building façade on Pireos Street

Entry citation

Kaltsa, M. (2015) Project Athens-Attica 2014, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/athens-attica-2014/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.36

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- ΥΠΕΚΑ (2010) Αθήνα – Αττική 2014. Αθήνα.