2017 | May

The pattern on which the «shirt» of the modern city is sewn each time is the result of the dialectic between order and disorder, rhythm and arrhythmia, regularity and exception, and most certainly the result of the dialectic between general laws and local protocols of space usage (Stavridis,2006).

In the city of Athens and more specifically in its centre, there are lively streets, bright commercial avenues, noisy and ceremonial public spaces (Pettas,2017), streets suitable for morning and evening strolls. However, the spatiotemporal discontinuity of the modern city means that not every road is taken by every person. There are roads where a special and informal exclusion takes place: «strange» roads, more suspect, neglected and dirty, illuminated at night solely by small lamps above the entrance of some houses. In Athens, these are the roads where brothels cluster.

Space cannot be defined as an urban feature prior to habitation. It is articulated via a system of discriminations and correlations. Roads like these, especially during night-time, offer an alternative meaning and a non-mainstream social experience, which cannot be shared by everyone. Is this perhaps a case of an «informal prohibition» of a gendered -and not only- mediation of this experience, due to the multiple risks of these enclaves? It is certainly the case that in brothels streets, the majority cannot join the shadows that wonder day and night looking for «something of their taste» or for brothel-hopping. Here, local protocols are of limited use.

Although this paper is not focusing on the history of brothels in the Greek capital, it is worth pointing out that prostitution was a well-established social phenomenon in classical Greece, and actually a state-run activity (see for example https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prostitution_in_ancient_Greece and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prostitution_in_ancient_Rome). One of the most decisive factors for the clustering of prostitution in specific urban locations, were public health regulations (Korasidou, 2002). Indeed, the regulatory directive of the Ministry of the Interior of the newly established Greek State in the 19th century as well as police circulars and subsequent laws, evidence the state’s effort to protect public health. It tried to do so by halting the spread of deadly sexually transmitted diseases, that were obviously connected to prostitution. Prostitution was recognised as a profession by the «Directive on public girls and brothels» of the Ministry of Interior in 1834 (Korasidou, 2002: 125). Permission for running brothels was granted by the police.

Since then, all regulatory directives and all relevant laws aimed to achieve control of prostitution not only in order to reduce sexually transmitted diseases, which was the official argument, but to eliminate the «moral offence» caused by the presence of prostitutes in neighbourhoods and streets, and mainly to control abnormality (Korasidou: 2002, Tzanaki: 2016). The most important such legislation was Law 3032 / 1922: Measures to control sexually transmitted diseases and prostitutes, that defined the requirements for running brothels. When it legalised prostitution and restricted prostitutes in specific areas and neighbourhoods in order to effectively control them, the Greek State did nothing more than follow the practices of other European countries, such as France. Prostitution was tolerated so long as it was controlled (Korasidou: 2002).

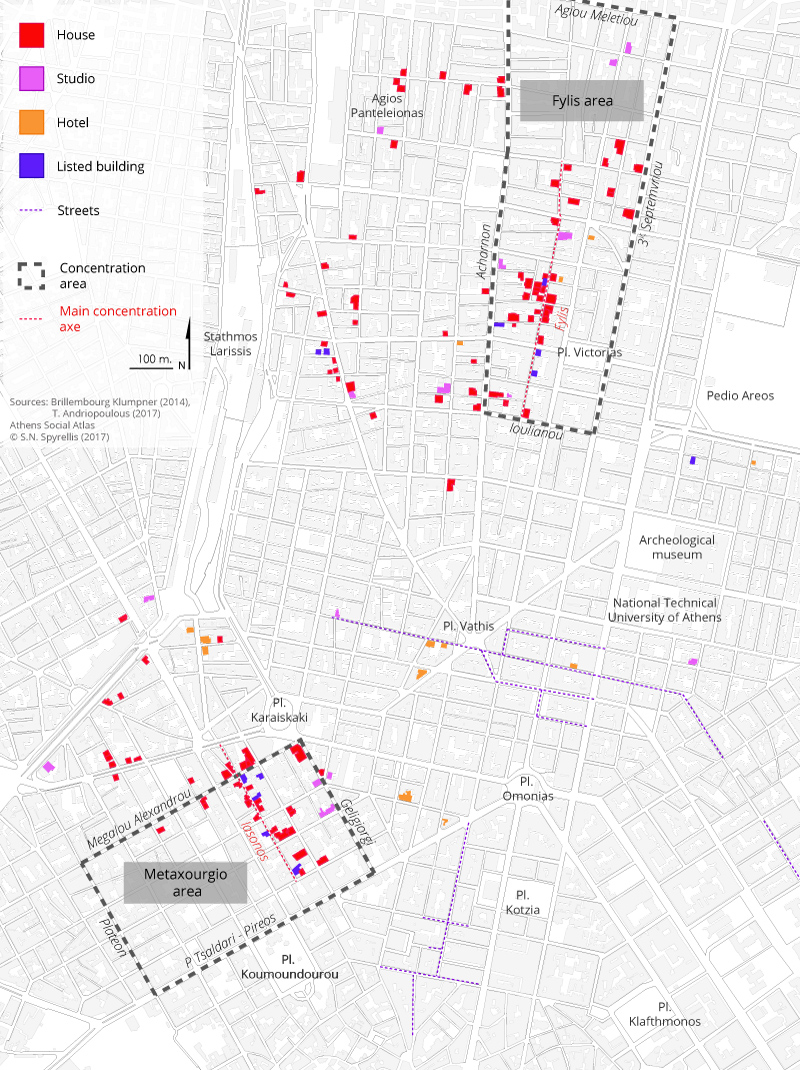

Map 1: Prostitution in central Athens.

Nowadays in Athens, old, traditional brothels are located south of Omonia Square within two sizeable rectangular areas. More specifically, the first and largest rectangle, is circumscribed by Tritis Septemvriou Str, Agiou Meletiou Str, Liosion Str and Ioulianou Str. Within this area, the density of brothels increases around Fylis Str, in a rectangle circumscribed by Heyden Str, Aristotelous Str, Feron Str and Acharnon Str. Fylis Street, in the center of the rectangle, has more brothels compared to the other adjacent roads. Although the Fylis Str area is gradually losing its prominent position in this business, it still remains the Trouba of Athens (photos: 1-6) [1]. The second rectangle in the Metaxourgio area, is circumscribed by Pireos Str, Plateon Str, Megalou Alexandrou Str and Deligiorgi Str. In this case, Iasonos Str functions in a way that is similar to Fylis Str (photos: 7-12).

Photos 1-6: The Fylis area

Unlike what is going on in Fylis Str., during the last few years, the social composition of the brothel clientele in the Metaxourgio area has substantially changed, towards a more socially and ethnically mixed crowd. The social composition of the residents of the neighbourhood, primarily immigrants (Μπαλαμπανίδης, Πολύζου, 2015) and marginal groups and individuals, has something to do with it. However, approximately the same social change is taking place in the composition of the population in the area around Fylis Str despite its middle class past. The key reason for the change in Metaxourgio is that the vast majority of brothels located there accepts immigrants as clients, unlike brothels in the Filis Str. area. One of the reasons why brothels in the Filis Str. area charge twice the price of brothels in Metaxourgio, apart from the attempt to preserve a sense of prestige, is that in this way they can exclude immigrants not onlydirectly by applying racist discriminatory criteria but via the market mechanism as well. Having said that, immigrants can find an offer of half price only a kilometer away [2].

Photos 7-12: The Metaxourgio area

The majority of brothels is housed mainly in old neoclassical and almost derelict houses (mostly in Metaxourgio), either in specially arranged ground floors (mostly in Fylis area) or in basements. Quite often, more than one brothels can be found in one house. During opening hours, brothels switch a small light on above their front door, which used to be red in the past (photo:13). This is where the title of the award-winning film The Red Lantern came from. The film describes the miserable life of prostitutes in Trouba and the term «traditional brothels» derives from the way brothels operated there.

This term is used to contrast the brothels of Fylis and Metaxourgion to an abundance of a new type of brothels, Studios (photos:14-16). These can be foundway to Iera Odos Str, as well as in other locations, such as in Vrilissou Str (in the Polygono ring road), in Frantzi Str in Votanikos or in Sygrou Avenue. In this case, the sign usually has the word Studio together with the address number of the establishment on it. The practices are the same as in the «traditional» type of brothel, but the service offered is not for the mass-market . There is a clear difference, compared to the “traditional” brothels in the sanitary conditions and the time available to clients regarding provision of services. The prices are three to five times higher than the “traditional” brothels and hence low income immigrants are excluded from these establishments too. It is not a coincidence that this type of brothels appeared at a time when these areas began to have high concentrations of immigrants, to satisfy market demand for “quality services” [3].

Photos 13-16: A new type of brothels: the Studios

In this case, contrary to Bauman, who called postmodernity “fluid modernism” (Bauman, 2000: 8), postmodernism ceases to be fluid since it modifies existing forms without changing their context. Here, the remains of modernity are simply solidified into places where new regularities take the place of the old. For this reason, brothels also include studios.

Brothel is a word which derives from the French word borda that meant the maid’s house; later the Italian bordello/ bordel acquired todays meaning, although originally it meant a hut outside a village where a prostitute lived (Petropoulos, 1991). Despite the efforts to gentrify areas where brothels cluster and although the clustering of such use [4], is against the law, brothels, remain the same through time, “identical and uniform”, as Nikos Kavvadias describes them in his poem Paralilismoi. When the poet, described the similarities between “houses of prostitutes”, the “snowy white but mournful schools of the western world” and the “dirty and dark bows” of freight ships, he mentioned that what was missing from all of them was “motion, spaciousness and pleasure”. The same humidity inside, the same ruins inside and outside.

What could, however, the brothel symbolise in a postmodern era when diversity and the ephemeral are mystified ? What could it symbolise when the end of memory has become an ideology and social culture favours “products ready for use” and “instant satisfaction requiring no effort”? (Bauman 2006: 29). What kind of memories could the remains of a city create, a city where rules, rhythms and behaviours have now changed even in finding a paid sexual partner? What have we inherited from these non-places (Auge, 1995), these unimaginable and, according to Foucault “extreme heterotopias” of urban fabric? (Foucault, 2012: 269). For there are times when even this tacky and impersonal vulgar love can bequeath some monuments to the future.

Is the creaking of an old and rotten door opening in a room not a trace? Could these transformations of a fleeting paid sexual contact leave behind such traces today? And if words are not only products of reality but carrying its images, what other words could be used to describe in the future the legendary teenager “brothel-hopping” in a brothel area? What remains from a sexual encounter in an impersonal hotel or from an online erotic «contact» (cyber sex)? How could we imagine Paris in the 19th century without the noisy “brothel-hopping” described Guy de Maupassant? Could Alexis Damianos make the film Evdokia today, using a call girl as the main character?

Brothels are one of the few remaining aspects of modernism where universality is neighbouring regularity but not necessarily similarity. The strangeness of this condition is that the brothel serves a traditional process from which non-familiar situations emanate regularly. Aren’t all heterotopias, spaces of non-familiar? They originate outside of the spatio-temporal order, that normally shapes heterotopic new experiences and provision relationships? Brothels, as heterotopias, are places charged with the temporariness of dwelling, places where the rules, although known, remain unwritten. The norms governing their function are oral. This is probably a «pre-modern» element that survives to the present.

The brothel performs the dual function of rescuing regularity through the simultaneous preservation of intimacy associated with the past. It is a tradition that is not necessarily associated with the repetitive use of space, but with the security of regularity, of the possibility of immediate selection and with the confidence of visibility.

Perhaps, what finally endures is not the brothel but everyone who is searching for “freedom” in desire. This desire however has already been structured as peculiar intimacy or unfamiliar regularity. That freedom may eventually boil down to a temporary look at one’s own face in a mirror during the awkward time of waiting in the “living room” -perhaps also in the bedroom later on. The awkwardness of those moments however is underpinned with the familiar illusion of the “omnipotence of choice”.

The brothel’s resilience could be connected to this paradox, to the non-sensical expectation that if the condition mentioned above is removed, in this extreme heterotopia, the place of the prostitution will become a place of mutual desire. In this case, heterotopia validates its precariousness as the possible metaphor for a spatialised utopia which does not seem impossible any more.

[1] Trouba is a neigbourhood near the Piraeus port which comprised a notorious brothel and infamous bars area since the beginning of the 20th century. The mayor of Piraeus -taking advantage from the period climate of the newly established dictatorship in 1967- closed the bars and evicted the prostitutes. This marked the end of Trouba as a prostitution area, but the name refers to a legendary brothel area in the collective memory of Athenians.

[2] People can be instantly excluded from entering brothels not due to their nationality but due to their color. There were cases where a demand was made of dark-skinned natives or foreigners were to speak some words in Greek, in order to be accepted or not.

[3] Without implying that prostitution emerged with the development of capitalist relations of production, the “erotic product” has been completely transformed in the context of these relationships, where everything, goods and people have and must have an exchange value,. It is known that for years the provision of this “product” is one of the most profitable, and most notably illegal, activities, with Sex Trafficking being a prominent example.

[4] If someone reads the fourth article of Law 2734/1999 which currently regulates the conditions of brothel function and was to visit one of the brothel areas afterwards, he/ she would be able to ascertain the conditions of illegality under which almost all brothels operate.

Entry citation

Andriopoulos, T. (2017) Brothels: houses which stood the test of time, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/brothels/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.71

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Bauman Z (2006) Ρευστή αγάπη. Για την ευθραυστότητα των ανθρώπινων δεσμών. Καράμπελας Γ και Ζουμπουλάκης Σ (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Εστία.

- Foucault M (2012) Ετεροτοπίες και άλλα κείμενα. Μπέτζελος Τ (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Πλέθρον.

- Κορασίδου Μ (2002) Όταν η αρρώστια απειλεί. Επιτήρηση και έλεγχος της υγείας του πληθυσμού στην Ελλάδα του 19ου αιώνα. Αθήνα: Τυπωθήτω.

- Μπαλαμπανίδης Δ, Πολύζου Ι (2015) Αναχαιτίζοντας τάσεις εγκατάλειψης του αθηναϊκού κέντρου: η παρουσία των μεταναστών στην κατοικία και στις επιχειρηματικές δραστηριότητες.Στο: Μαλούτας Θ και Σπυρέλλης ΣΝ (επιμ.), Κοινωνικός Άτλαντας της Αθήνας. Ηλεκτρονική συλλογή κειμένων και εποπτικού υλικού, Αθήνα. Available from: http://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/μετανάστες-κατοικία-και-επιχειρήσει/.

- Πετρόπουλος Η (2010) Το μπουρδέλο. Αθήνα: Νεφέλη.

- Πέττας Δ (2017) Η παραγωγή του χώρου σε συνθήκες σύγκρουσης. Στο: Μαλούτας Θ και Σπυρέλλης ΣΝ (επιμ.), Κοινωνικός Άτλαντας της Αθήνας. Ηλεκτρονική συλλογή κειμένων και εποπτικού υλικού, Αθήνα. Available from: http://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/άρθρο/χώρος-σε-συνθήκες-σύγκρουσης/.

- Τζανάκη Δ (2016) Ιστορία της [μη] κανονικότητας. Πάπαρη Κ (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Ασίνη.

- Augé M (1995) Non places. Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermoderity. Howe J (ed.), London, New York: Verso.

- Bauman Z (2000) Liquid modernity. 1st ed. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Brillembourg AJ and Klumpner H (2014) Reactivate Athens / 101 Ideas. Final research report for the Onassis Cultural Foundation (limited distribution). Zurich.