Carnival in Athens: centre and neighbourhoods, 1834-1944

Potamianos Nikos

Culture, History, Quartiers

2024 | Jan

The article explores the relationship of the center of Athens with its periphery, the neighborhoods of the city, and the way in which this relationship changes from the first years that Athens became the capital of the modern Greek state until World War II. This relationship is proposed to be connected not only with the growth of Athens and the urban structures, but also with the class relations, the power of the bourgeoisie, its cultural hegemony or the extended autonomy of the popular classes. The processes of centralization and decentralization are studied through the example of the celebration of the carnival and its transformation over a period of a century. Carnival events are undergoing significant changes, as is the way they are imprinted in the space of the city.

Spatial theorists such as Lefebvre (1977) and Castells (1979) have identified centrality as a key component of urban life and have discussed the multiple levels of centrality (economic, political-institutional, ideological-symbolic, the centre as “milieu of action and interaction”) – which do not necessarily have to coincide in the same space.

The way and intensity with which activities are concentrated in urban districts and the area of concentration are obviously subject to change. The relationship between the city center and the periphery is generally subject to change: a relationship of subordination and control, according to Merriman (1991), but which is constantly in question. State mechanisms and upper classes are based in the center, and the periphery of the city, even when not inhabited by “dangerous classes”, is a space in which power exercises weaker control.

In this paper the processes of centralization and decentralization will be examined, as well as the relations that develop between the center and the neighborhoods of Athens during a century, as they appear in the celebration of carnival (Ποταμιάνος, 2020). In short, the pole of the urban center is constantly strengthening until the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, when the concentration of activities peaked; then this trend is stopped and the neighborhoods of the city seem to gain a new autonomy.

During the century that passed from when Athens became the capital until the Second World War, the area and the population of Athens multiplied rapidly: from the 30,000 inhabitants of 1853 to the almost 500,000 inhabitants of the municipality of Athens and the 1,100,000 of the whole region of the capital (including Piraeus) in 1940. Obviously the center is constantly shifting and being redefined all this time, for example with Omonia being initially located on the outskirts of the city and then becoming its dominant transport hub. What we are interested in here is not to determine the space occupied by the center but to examine its relationship with the rest of the city. On the one hand, the need for integration and coordination of urban activities increases, as the city expands; on the other hand, the strengthening of the bourgeoisie and the state implies, also, the increase of the importance of the city center from a political, administrative and symbolic point of view.

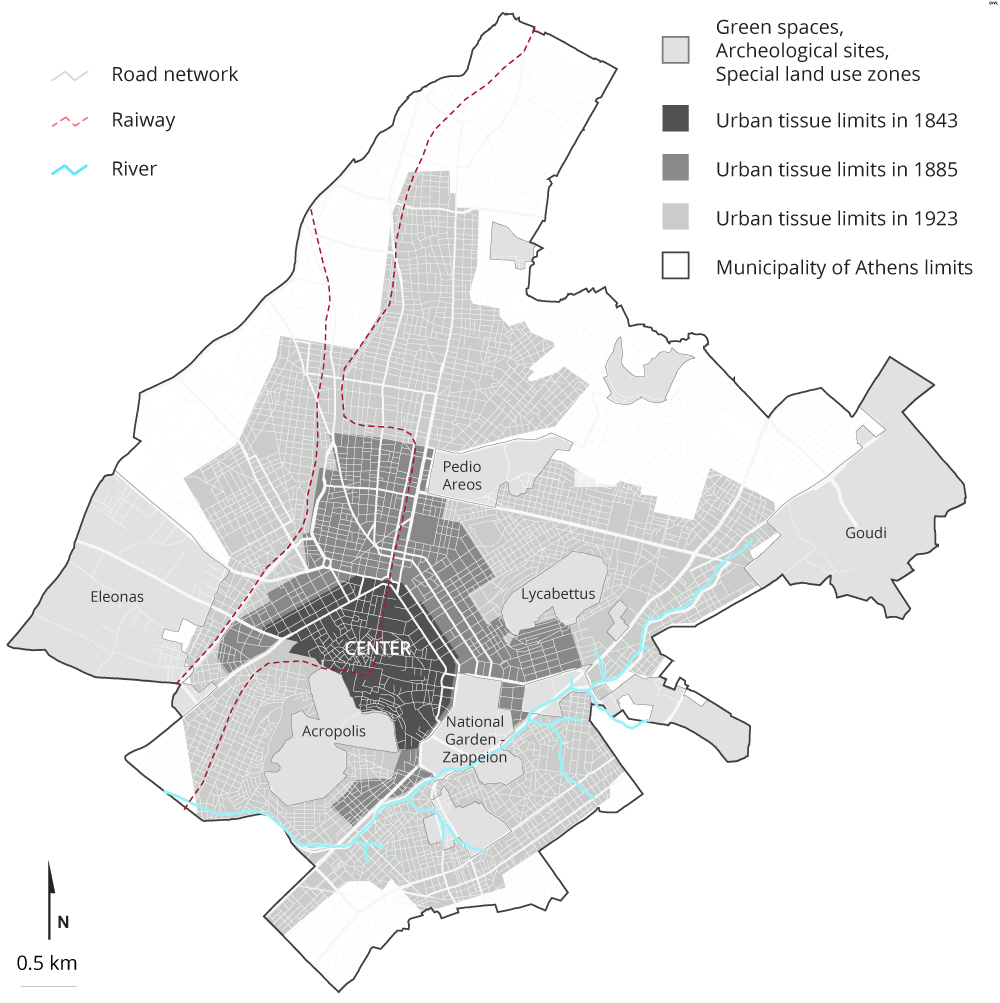

Map 1: The expansion of the urban fabric in the Municipality of Athens 1843-1923

Thus, the character of the center as a public space, bright, noisy, crowded, dominated by men and defined by large public buildings, squares, tram (and later bus) starting points, and supra-local entertainment centers, dominates literature and the press. It is a space that is gradually getting rid of the most disturbing craft activities, in which innovations in urban infrastructure such as electricity or asphalt are first applied, and in which the first cracks appear in the face to face society as Athens grows (Ποταμιάνος 2015: 44). Nevertheless, the center remains a place of residence throughout the period, and in fact a residence of the middle class (Μπουρνόβα και Δημητροπούλου, 2015).

The reinforcement of centralization in the structures of the city takes the form not of the retention at the center of all the activities that existed in it before (this did not happen, for example, with the commercial functions, which were largely diffused in the neighborhoods), but that of the subsumption of neighbourhood activities to the centre, bringing them under its control. For example, neighborhood grocery stores that procured their wares from the central vegetable market largely replace both going to the centre for shopping fruits and vegetables and the street vendors who went around the neighbourhoods selling produce from their market gardens on the outskirts of Athens and the surrounding villages (Ποταμιάνος, 2018). The forms of direct communication between the neighborhoods, therefore, are limited and the routes from the center to the neighborhoods and vice versa become more and more frequent, something that is not only due to the radial structure of urban transport. Typically, the election demonstrations, when they appear in Athens, are initially experimented with routes through various districts (Μη Χάνεσαι 1 and 2 July 1883, Ακρόπολις 5 July 1887), but they quickly standardize their route on the main avenues.

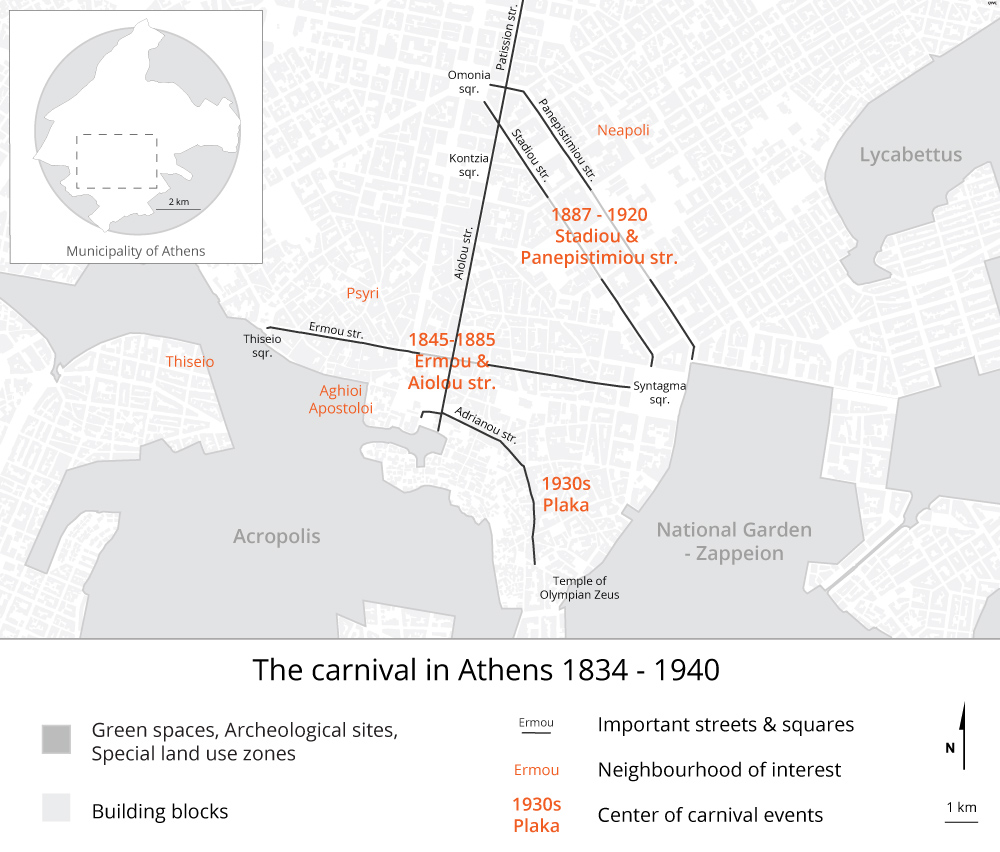

At carnival, in the middle of the 19th century, a gathering of disguised persons and masquerades and in general of various events is reported on the afternoon of the last Sunday (“Cheesefare Sunday”) at the junction of Ermou and Aiolou streets; however, the same descriptions give the impression of a carnival activity quite diffused in the city (eg Ευτέρπη 1 March 1849: 310-311). As the crowd grows, the police in 1872 forbid the passage of carriages and carts from Ermou and Aiolou streets on Cheesefare Sunday to avoid accidents (Μπουκλάκος, 1874: 341-2). Along with the concentration trends, however, many decentralized practices are developed, such as masquerade and folk spectacle tours in the neighborhoods. After all, it is in those years that we have to place the heyday of a carnival practice that we learn about mainly afterwards from its “obituaries”: the mass exchange of masquerade visits “from neighborhood to neighborhood” (Εφημερίς των συντεχνιών 3 March 1891). In 1876, Angelos Vlachos wrote that “the disguised members of the lower classes ran through the city from Psyrri to Plaka and from Neapolis to Agioi Apostoloi until late at night” (Εστία τ.1, 1876: 91-93∙ see Αθάνατος, 2001:52).

The gathering of the crowd in the center for the carnival will intensify from 1887 to 1914, when carnival parades are organized by the “komitata”, committees of the upper bourgeoisie with the aim of “civilizing” the public carnival and attracting visitors to Athens. The focus of the events then shifted further towards Stadiou and Panepistimiou streets, leaving Ermou street with a more peripheral character (eg Σύλλογος 29 February 1888). The most important thing, however, is that the new focus of activity gathers larger crowds according to the image given by our sources. In 1900-1901 “streams of people” are mentioned flowing from the neighborhoods to Stadiou street, and an increase in burglaries in the neighborhoods during the hours that their residents were in the center to watch the parade (Εσπερινή Ακρόπολις 14 February 1900, Σκριπ 7 February 1901, Εστία 17 February 1914).

Papadiamantis in 1899 sets one of his Athenian short stories (“Οι παραπονεμένες”) in a neighbourhood during the carnival parade, the “time of the great influx in the centers, of the great desolation in the outskirts”. It is no coincidence that in Papadiamantis’s story, the group of people left behind in the neighbourhood consists of women; however, the transformation of public carnival in the main streets brought about by the parades favoured the increased presence of women in the centre in the following years, and generally contributed to their achieving access to the public space.

Developments such as the ongoing disconnection of the carnival from the community and the acceleration of the tendency to turn its events into more impersonal urban spectacles, performed by people who made a living from them, rather than being connected to neighbourhood and immigrant communities, certainly contributed to the increase in the concentration levels of the Carnival celebration. The broader context of this development was the rise at international level of a mass culture “more focused on individual consumption than on collective participation” (Vigarello, 2004: et seq.).

In addition, however, the initiative of the committees and the importance it acquired makes clear the relationship between the reinforcement of the role of the city center and the strengthening (demographic, economic, social and political) of the Athenian middle class. The bourgeoisie lived in the center both literally and symbolically: in the center as the place of political and economic decision-making and as the emitter of the values and symbols of power and authority.

The increasing importance of the middle class (and especially their more Europeanized and “modernizing” fraction), and the attempt to deepen their hegemony to levels corresponding to their new power, also acquired a spatial expression: the “reoccupation” of the centre of Athens (meaning the streets of the areas in which they lived) and its appropriate configuration during carnival, as well as an increase in centralization at the level of both state and city. Here it is worth recalling Gruppi’s (1977: 84) definition of hegemony as the ability to unify a social whole that is not homogenous, and transferring it from the level of ideology to that of the city.

Map 2: Epicenters of carnival events in Athens 1834-1940

It seems, moreover, that at the beginning of the 20th century the spatial dimension of the contrast between bourgeois and popular culture has become more intense. Α striking example is provided by the report in the Estia newspaper in the summer of 1901 from Thissio Square, where there was a flourishing district of popular entertainment venues: every now and then the trams brought “groups of sightseers from the rather Europeanized neighbourhoods, coming to see the festivals of the people” (Χατζηπανταζής, 1986: 154). Ι did not detect any similar exploration mission for the carnival period, however the spatial-social dimension of a strong cultural difference was highlighted by complaints in the newspapers about improper behaviour in the main streets during carnival: in 1905 the “crude pranks” of the alleyways of Psyrri were said to have moved to Stadiou Avenue, “the great open-air salon of genteel japes” (Σκριπ 1 March 1905 -cf Σπυροπούλου 2010: 129 for the comparison of Stadiou with s bourgeois salon by the novelist Spandonis in 1893). while in 1920 there is a report of a “brutal invasion of the main streets by gangs of layabouts” (Καιροί 19 January 1920). In 1915 a journalist appeals to the police to remove the “loathsome gangs of masqueraders” who ask for money for the spectacle they offer with the camel, the maypole, tumbling somersaults and “other rubbish”, or at least to “confine them to the outermost neighbourhoods of Athens, so that the people of the centres may escape this aesthetic nausea” (Ακρόπολις 22 January 1915). The “outermost neighbourhoods”, then, are identified as the natural habitat of these spectacles, which lies far from the centre, the “showcase” of the city and, above all, a place where people of more refined culture reside.

The degree of concentration at carnival events peaked at the turn of the 20th century, and then fell. The critical factor here was the more general transformations that took place in carnival entertainments, moving away from public festivities and spectacles towards dancing (Ποταμιάνος, 2020: 263-267). Of course, the public entertainment venues in the centre of Athens were very crowded, while the carnival balls of the various associations also tended to be held in locations in the centre. It remains a fact, however, that the neighbourhoods were in a better position to compete with the city centre in attracting people to entertainment venues rather than in offering urban spectacles. Moreover, the progress achieved in gender relations, as regards women’s ability to circulate in a public space (Ποταμιάνος, 2020: 232-234), made it less important to create a “civilized space” in the centre of the city where harassment was least possible. From this point of view, then, as well, there was less need for concentration

Of course, after the last parade organized by a komitato in 1920, centrally organized events and parades will be repeated in the 1930s in Plaka, with the “Carnival of old Athens” organized by the Tourism Organization, the municipality and a committee of residents (Βλάχος, 2016: 189, Ελεύθερον Βήμα 2 March 1932, Αθηναϊκά Νέα 26 January 1934 etc). This initiative made Plaka the center of the (weakened) carnival in Athens in the following decades (eg Μπρούσαλης 1963), and seems to have contributed more generally to the establishment of Plaka as a center of supra-local entertainment with its taverns, later bars, etc. It is clear, however, that it was now a small carnival parade, with a much smaller crowd.

My hypothesis is that this reduction in concentration is linked to an increase in the autonomy of popular culture and the popular neighbourhood. The further spatial expansion of Athens, with the doubling of its population in the 1910s and 1920s, would de facto have reinforced various neighbourhood and inter-neighbourhood centres, and a more autonomous life of the “outer” neighbourhoods. As early as 1916, a columnist describes “small neighbourhoods” as self-sufficient, independent units: “there are people who, except for an evening stroll as far as Syntagma Square, do not travel at all to the so-called centres. They belong to the neighbourhood. Its café, its pedestrian area, its pretty young girl, its small theatre, its bustle, become enough from day to day to satisfy their every interest” (Πατρίς 30 June 1916). The classic play “Fintanaki” (1921) written by Pantelis Horn seems to express this awareness, setting its plot in a miniature version of the popular neighbourhood, the “courtyard”, and presenting it as a complete world within which the lives of the inhabitants of the houses surrounding the communal courtyard unfold. Obviously it would be wrong to think of the neighbourhood as an enclosed space, but between the wars it appears to become more self-sufficient and self-contained; the publication of neighbourhood newspapers such as the Φωνή του Παγκρατίου in 1930 is typical of this development. A sense of greater isolation and self-sufficiency was definitely also due to the limited interactions between the native Athenians and the refugees who came from Asia Minor in 1922 and settled in new working-class districts around Athens.

The popular neighbourhood, in these circumstances of increased self-containment, was the space in which a new popular culture arose during the interwar years, exemplified in the emblematic music and overall culture of rebetiko. The evidence I have collected, however, does not appear to indicate any particular dynamism in the field of carnival culture. Older popular spectacles such as the camel or maypole were not restored to their former glory (actually they are often described as being in decline: Έθνος 5 March 1924, Πρωία 3 March 1929 etc), nor were satirical masquerades revived. The Asia Minor refugees, with the possible exception of the practice of flying kites on Clean Monday (as Cleo Gougouli has pointed), did not leave their mark on carnival culture, as they did in fields such as music or cooking. A description of carnival life in the neighbourhood of Agia Triada published in 1924 may be representative: “We did not see the crowds of yesteryear, the camel, the maypole, and the Fasoulis puppet theatre, nor did we see masqueraders. We did see a different crowd, of merrymakers on carts who sang various carnival songs, while in many alehouses others danced.” Festivities involving European and Greek dances also took place in houses, “and it is rumoured that on the last days of carnival, balls will be held at all the alehouses of the neighbourhood, large and small, which will be temporarily transformed into dance halls to which, they say, only masqueraders in costume will be allowed entry” (Εύα 23 February 1924).

The neighbourhood streets would certainly have been busier, especially considering the lack of space in the poorer homes. Let us bear in mind that this activity was only disseminated outside the neighbourhood to a limited extent; it is mentioned that the masqueraders of the interwar period largely stayed within their own neighbourhoods, without leaving them to meet in the centre (Παπαζαχαρίου, 1980: 205-206), This was a reversal of the tendency towards concentration observed in the previous period, a reversal which might be correlated, probably not arbitrarily, with the crisis of middle-class hegemony in the interwar years, which at the political level was expressed in a series of military coups (that is, with the increase in the use of violence and the decline of the institutionalization of political conflict: Κωστής, 2013). This tendency of the popular neighborhoods to become autonomous will reach extreme levels in the conditions of the Occupation of Greece by the Axis powers during the Second World War), and will culminate in the attempted military and political occupation of the centre of Athens, the seat of political power and the middle class, during the civil conflict of December 1944, by a Communist left based on the periphery of the city.

Entry citation

Potamianos, N. (2024) Carnival in Athens: centre and neighbourhoods, 1834-1944, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/carnival-in-athens/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.117

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Αθάνατος Κ (2001) Ταξείδι στην παλιά Αθήνα. Αθήνα: Δήμος Αθηναίων Πολιτισμικός Οργανισμός.

- Βλάχος Ά (2016) Τουρισμός και δημόσιες πολιτικές στη σύγχρονη Ελλάδα 1914-1950. Αθήνα: Economia Publishing.

- Κωστής Κ (2013) «Τα κακομαθημένα παιδιά της ιστορίας». Η διαμόρφωση του νεοελληνικού κράτους 18ος-21ος αιώνας. Αθήνα: Εκδόσεις Πόλις.

- Μπουκλάκος ΓΘ (επιμ.) (1874) Συλλογή των Αστυνομικών νόμων, διαταγμάτων, διατάξεων και κανονισμών. Αθήνα.

- Μπουρνόβα Ε και Δημητροπούλου Μ (2015) Κοινωνικο-επαγγελματική διαστρωμάτωση της πρωτεύουσας. Στο: Μαλούτας Θ και Σπυρέλλης ΣΝ (επιμ.), Κοινωνικός άτλαντας της Αθήνας. Ηλεκτρονική συλλογή κειμένων και εποπτικού υλικού, Αθήνα.

- Μπρούσαλης Κ (1990) Σερπαντίνες και κομφετί. Στο: Ψαράκης Τ (επιμ.), Ανθολόγιο της Αθήνας, Αθήνα: Νέα Σύνορα, σσ 21–24.

- Παπαδιαμάντης Α (1984) Οι παραπονεμένες. Στο: Τριανταφυλλόπουλος ΝΔ (επιμ.), Άπαντα, Αθήνα: Δόμος, σσ 193–198.

- Παπαζαχαρίου Ε (1980) Η πιάτσα. Αθήνα: Κάκτος.

- Ποταμιάνος Ν (2020) ‘Της αναιδείας θεάματα’. Κοινωνική ιστορία της αποκριάς στην Αθήνα, 1800-1940. Ηράκλειο: Πανεπιστημιακές εκδόσεις Θεσσαλίας.

- Ποταμιάνος Ν (2018) ‘Οι πλάνητες υιοί του Ερμού’: πλανόδιοι έμποροι στους δρόμους της Αθήνας 1890-1930. Στο: Χατζηιωάννου ΜΧ (επιμ.), Ιστορίες λιανικού εμπορίου 19ος-21ος αιώνας, Αθήνα: Εθνικό Ίδρυμα Ερευνών, σσ 111–145.

- Ποταμιάνος Ν (2015) Οι νοικοκυραίοι. Μαγαζάτορες και βιοτέχνες στην Αθήνα 1880-1925. Ηράκλειο: Πανεπιστημιακές Εκδόσεις Κρήτης.

- Σπυροπούλου Α (2010) Μορφές κατοίκησης στην Αθήνα κατά τα τέλη του 19ου αιώνα. Αρχιτεκτονικός χώρος και λογοτεχνία. Αθήνα: Νήσος.

- Χατζηπανταζής Θ (1986) Της Ασιάτιδος μούσης ερασταί… η ακμή του αθηναϊκού καφέ αμάν στα χρόνια της βασιλείας του Γεώργιου Α΄. Αθήνα: Στιγμή.

- Castells M (1979) The urban question. A Marxist approach. London: Arnold.

- Gruppi L (1977) Η έννοια της ηγεμονίας στον Γκράμσι. Αθήνα: Θεμέλιο.

- Lefebvre H (1977) Το δικαίωμα στην πόλη. Χώρος και πολιτική. Αθήνα: Παπαζήσης.

- Merriman JM (1991) The Margins of City Life: Explorations on the French Urban Frontier, 1815-1851. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Vigarello G (2004) Από το παιχνίδι στο αθλητικό θέαμα. Αθήνα: Αλεξάνδρεια.