Children's geographies in the neighbourhoods of Athens

Karampini Zoi|Micha Irini|Vallindra Eirini

Education, Quartiers, Social Structure

2024 | Jul

In this article we focus on children’s everyday places and their significance in Urban Studies. Our exploration is framed through the perspective of the socio-spatial dialectic and the relational structure of each place – ranging from the body, the chair, and the desk to the neighbourhood, the city and beyond. Embracing an interdisciplinary approach, we engage in dialogue with disciplines of Children’s Geographies, Critical Pedagogy, New Sociology of Childhood, and Critical Cartography. We aim to conduct a perspective for exploring the places in which children live and act through their views and embodied practices. Our objective is to highlight that focusing on children in research and education is a process of critically questioning what is assumed to be given and reconsidering our perceptions of childhood.

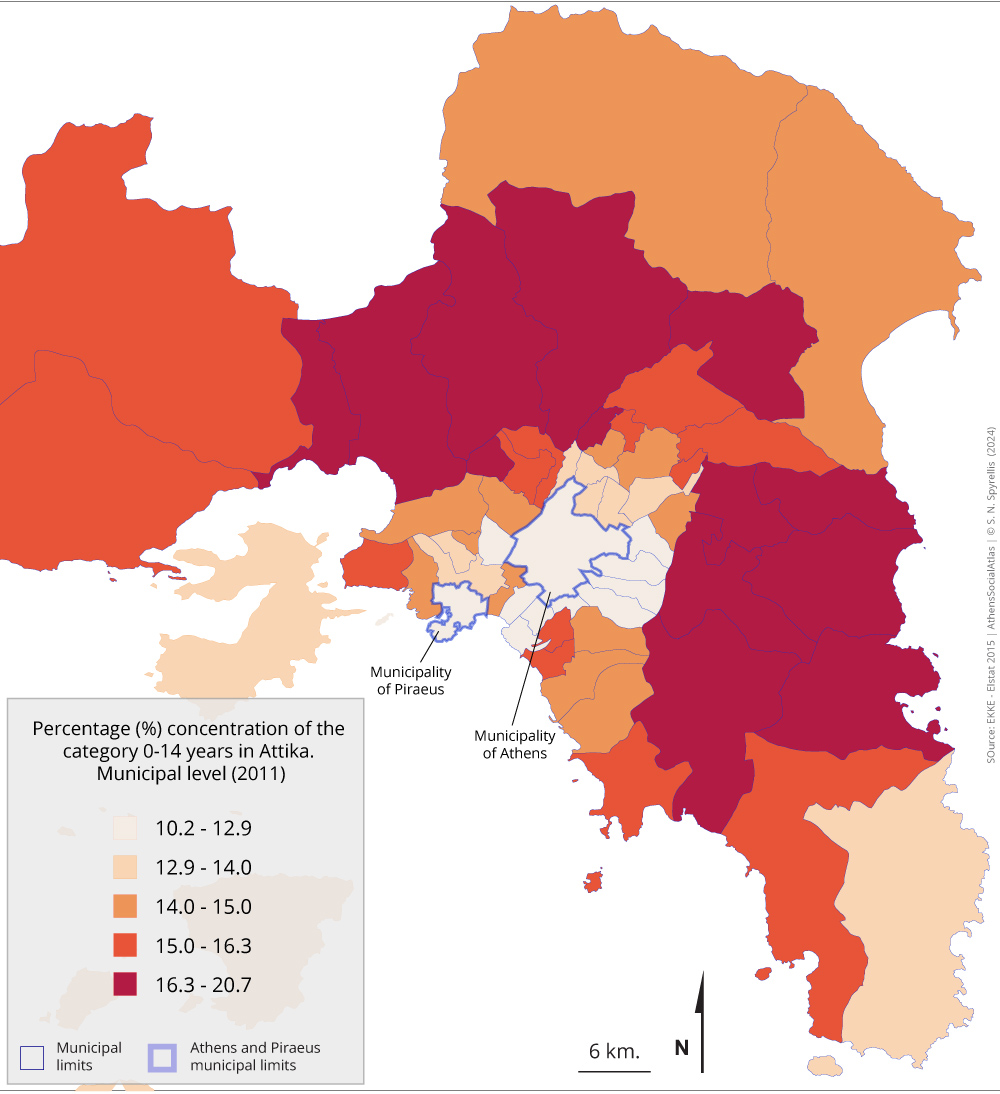

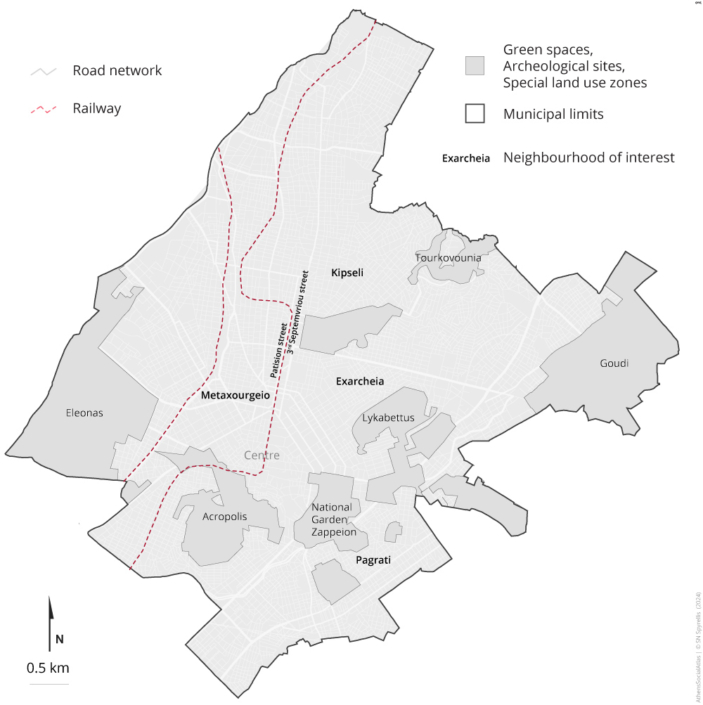

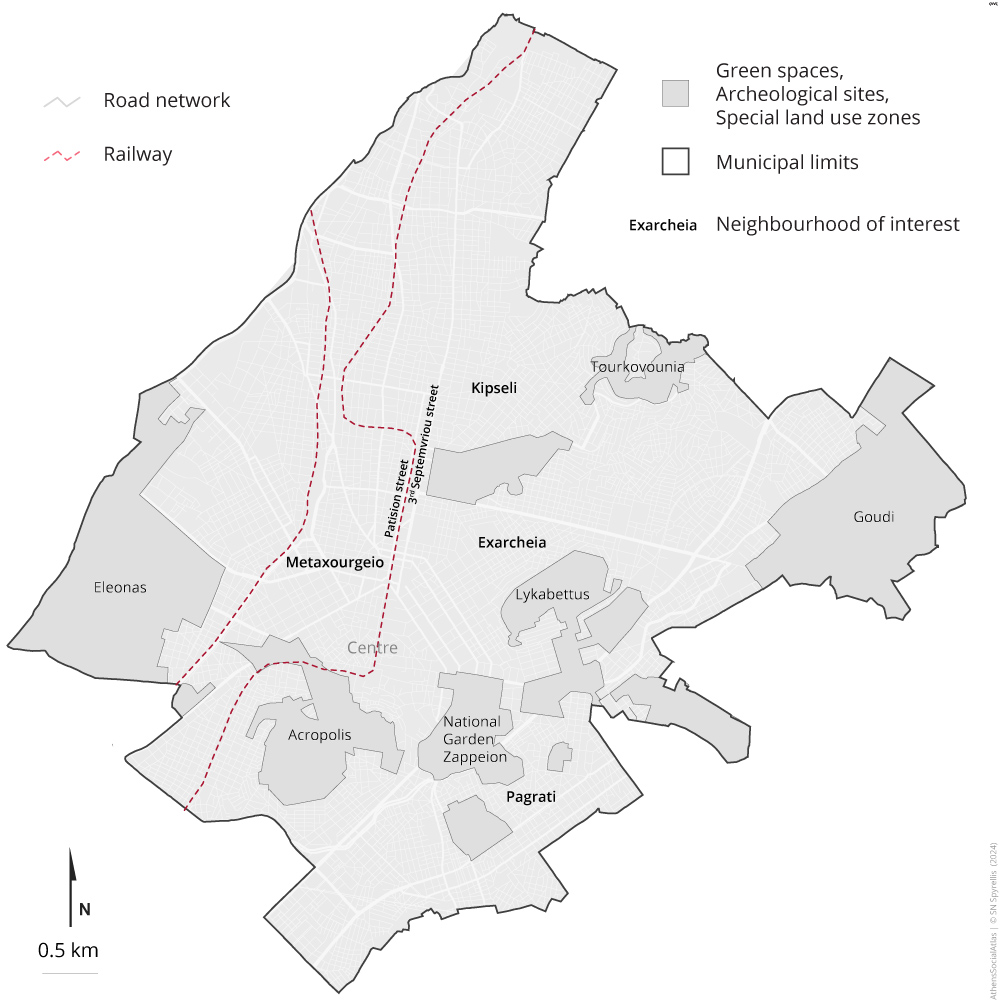

Through cartographic documentation of ethnographic research in Pagrati neighbourhood (with children 7-12 years old) and multiple educational workshops, both inside and outside the school context, in various neighbourhoods of Athens (Metaxourgeio, Exarcheia, Kipseli, Pedion Areos and the wider area between Patision and 3rd Septemvriou streets) (Map 1), we emphasize the importance of understanding children’s perspective on the city, as well as the need to integrate the socio-spatial dimensions of place into the learning experience. With this viewpoint, we propose a situated pedagogy, which is reinforced and practiced through exploration and mapping practices of place. Studying with the children in their everyday practices, we observe that their varied and differentiated spatial choices form a persistent dynamic in the city. Their mappings challenge dichotomous considerations, prompting us to reflect on adults’ tendency to place children in pre-ordered spatial arrangements.

Map 1: Municipality of Athens

Children’s geographies in research and education

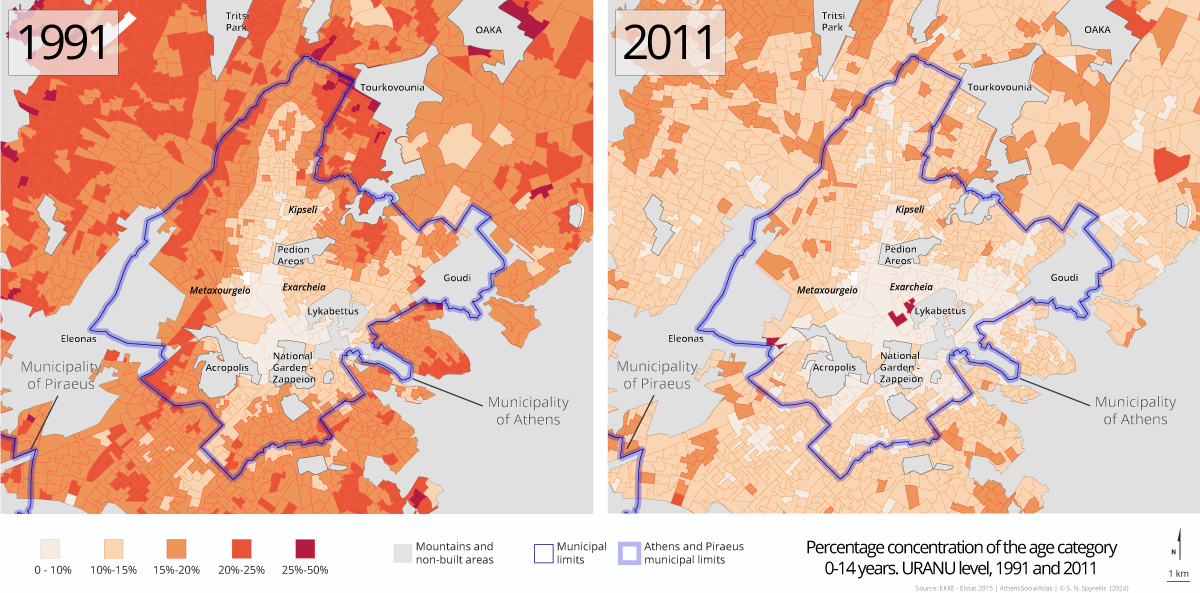

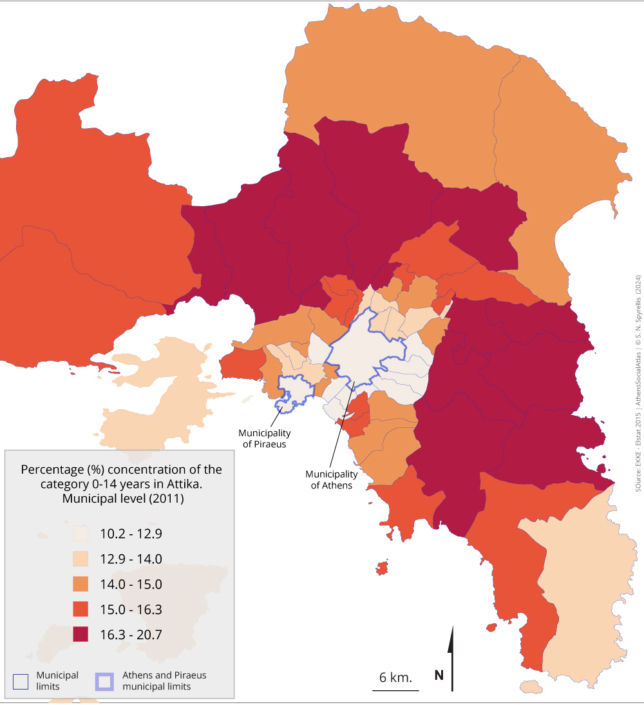

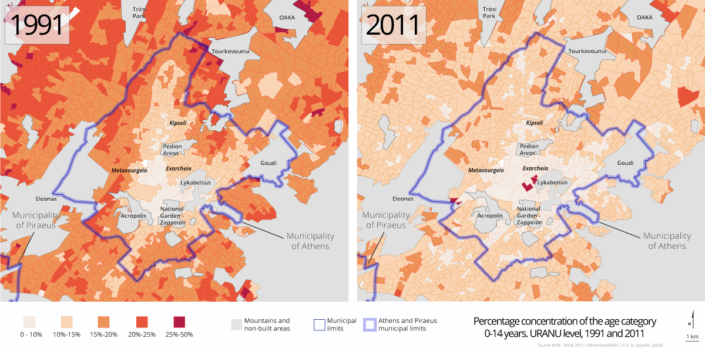

Children and young adolescents (up to 14 years old) constitute 13.9% of the population of Attica, a percentage reduced by 20.8% since 1991. The Municipality of Athens (Maps 2,3 & 4), in particular, maintains a similar percentage, depicting a relatively diverse population composition, despite its aging, which probably justifies the concentration of a significant percentage of elderly people (Maloutas and Spyrellis 2019).

Map 2: Percentage concentration of the age category 0-14 years in Attiki. Municipal level, 2011

Data source: ΕΚΚΕ-ELSTAT (2015)

Maps 3 & 4: Percentage concentration of the age category 0-14 years in Athens per URANU [1], 1991 and 2011

Data source: ΕΚΚΕ-ELSTAT (2015)

These youngest urban dwellers usually live more ‘locally’, appropriating and co-shaping their everyday places, developing practices and relationships. Spatial and social networks develop around children’s habits and routines, often forming the organizational backbone of each neighbourhood (Gayet-Viaud, Rivière and Simay, 2015). Yet their perspectives, concerns, and insights are often overlooked by urban policymakers, as there is a scarcity of focused studies on children’s habits in university education within disciplines of space (architecture, urban planning, geography…), nor in school curricula. In mainstream narratives, children are frequently referenced by their absence, such as in publications on the aging population and the problem of under-aging; οr in research on their exclusion from public spaces in the city, the risks they face from traffic, and the generally stifling urban environment. However, Athens’ children do not constitute a homogeneous population category. Instead, age differences in the city’s neighbourhoods intersect with various ethnic, gender, class, family, and other differences, shaping a multifaceted everyday life. Here, we endeavour to shed light on these multiple intersections, aiming to establish a perspective in urban studies that emphasizes children’s places, their spatial negotiations, and their explicit and implicit claims.

Since the 1980s, the theoretical elaborations of the New Sociology of Childhood have been destabilizing the categorizations of predetermined (natural) adulthood, shedding light on social factors that contribute to the formation of each child’s identity. By exploring the boundaries between childhood and adulthood, they also deconstruct the view of the child as a passive recipient of a prescribed, ‘normal’ course of socialisation. The visible presence and the acceptance of difference, as well as the consideration of children as agents challenge regulatory practices that objectify children’s interests and rights, seeking in the ‘here and now’ of their life in the city, their own perspectives, thoughts, everyday practices, and spatial inventions (Καραμπίνη, 2023: 17-18).

The above formulations, are aligned with approaches from radical geography, feminist and cultural studies, critical pedagogy, and postcolonial thinking. They develop a strong research interest in the socio-spatial parameters of childhood and emphasize the importance of space in the educational process. Different spatial scales and interconnections are thus highlighted, with the city emerging as a significant site for habitation, everyday life, study, and learning. These explorations form two converging disciplinary areas: children’s geographies (see Holloway & Valentine, 2000) and place-based education (critical pedagogy of space) (see among others Morgan, 2000) (Figure 1).

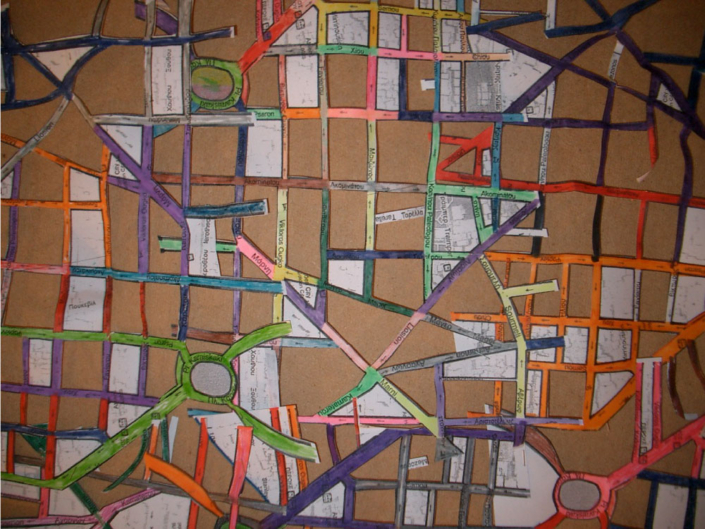

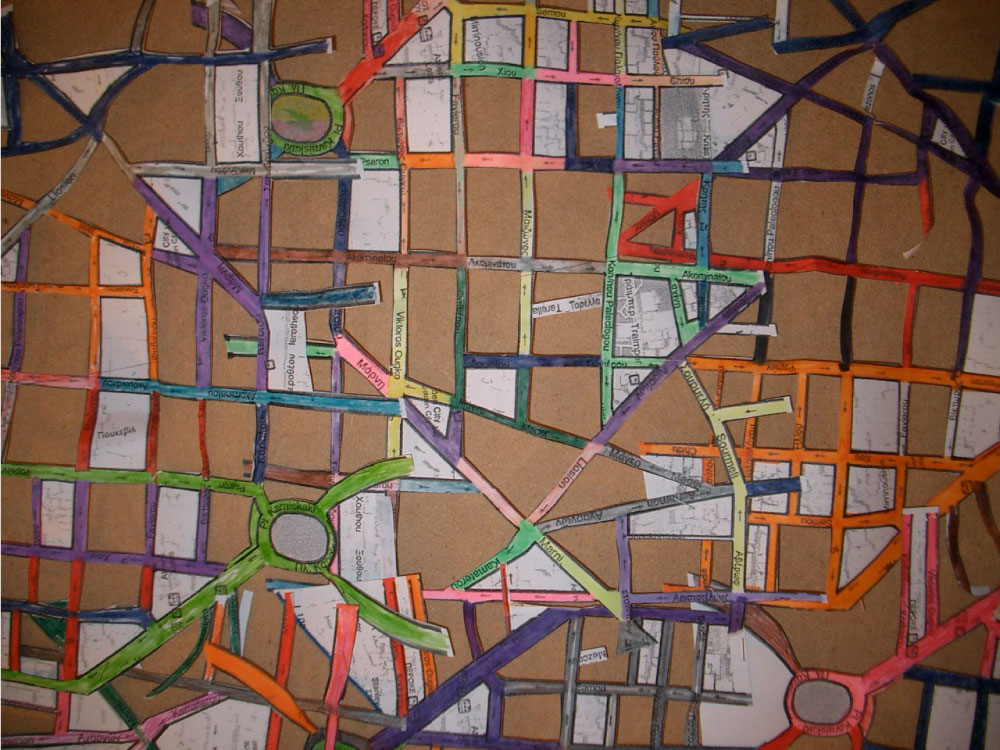

Figure 1: The chemin of the neighborhood: twelve maps cut and joined for us

Source: From the educational program ‘Between Two Squares: Vathis – Agios Pavlos, 2012-13’, https://elenakyla.wordpress.com

Children’s geographies have gradually developed since the 1990s, building upon earlier approaches by a generation of geographers in the 1970s who recognized children’s cartographic skills as a valuable research and educational tool [2]. Within the framework of an interdisciplinary dialogue they spotlight and map the exclusion of children from everyday urban spaces and advocate the viewing children as equal and integral members of the population, deconstructing the dominant notion that places them as a distinct (lower social) group -where entrenched narratives usually place women, migrant bodies, sexual heterogeneities, dyslexic or hyperactive students, and so on. Postcolonial approaches further contribute to this perspective by highlighting colonial mechanisms that undermine the multiple worlds of childhood under the lens of Western perspectives, but also the myriad networks that link children’s local experiences to global political-economic rearrangements (see Katz, 1994; Aitken, Lund and Kjørholt, 2007).

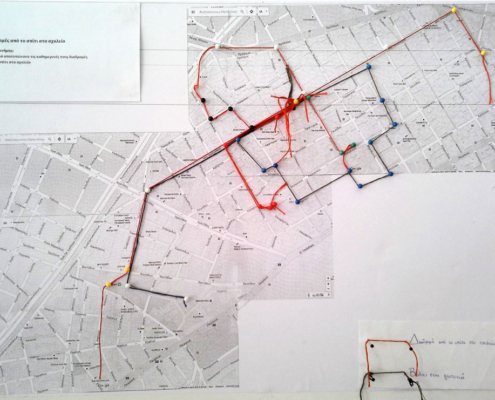

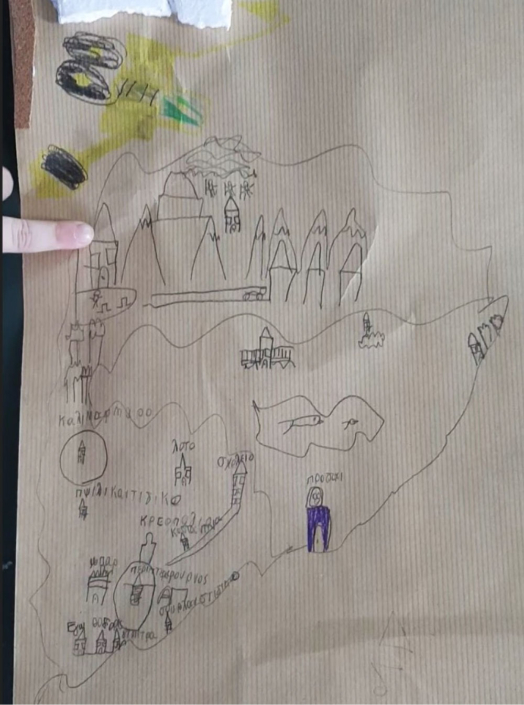

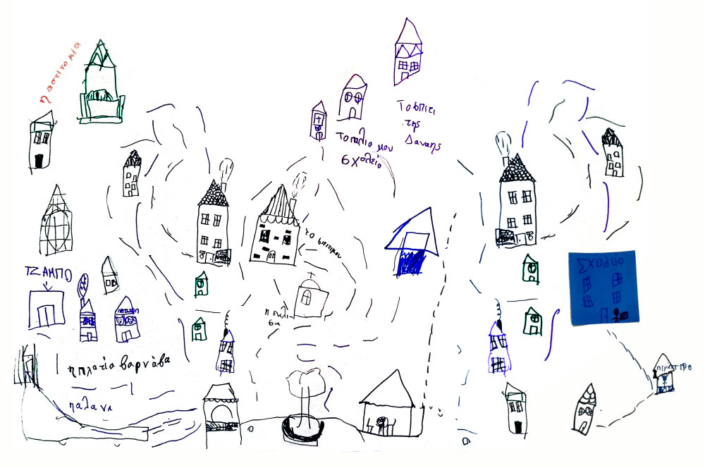

Drawing on geographical research on children’s everyday places, experiences and practices, diverse research elaborations seek ways to integrate the school neighbourhood into the teaching practice (see among others Smith, 2002; Gruenewald, 2003), to be used as a platform for learning, tacit knowledge and active participation in their communities (André et al., 2012). Critical considerations of cartography contribute to the shift towards studying the neighbourhood through appreciating and systematizing local knowledge. They push the conceptual boundaries of spatial representations beyond traditional school geographic representations (school maps and atlases), revealing new perspectives on space derived from personal and collective experiences (Harley, 1989; Crampton, 2001). These considerations shift the focus to social mapping practices, activating subjective socio-spatial perspectives and moving away from positivist approaches to the study of space (Del Casino and Hanna, 2005) (Figure 2). They highlight the multiple levels of knowledge that children produce about the world and encourage an understanding of their existence as integral to its spatial and relational dimension (Kitchens, 2009).

Figure 2: Mapping of the Pagrati neighbourhood

Source: From the experiential workshop ‘Mapping the Neighbourhood’ with children from the 1st grade of the 13th Primary School of Athens, 2020

This view differentiates the content and meaning of geography: it redefines our approaches to children’s spatial experiences, and the way we interpret space between the local and the global. In our approach, a map, a drawing, an experiential narrative does not describe in a neutral way what space is but studies what we do with space, imaginatively and politically (Gerard Toal in Graves and Rechniewski, 2015).

Children’s everyday places in Athens

In our country, the discourse regarding children’s geographies is still in its infancy, while the formal pedagogical curriculum is rather inhibiting its advancement. Nonetheless, over the past decade, there has been an emergence of ethnographic research and educational programmes examining the experiences and practices of children in the neighbourhoods of Athens, thus promoting a scholarly production that engages with the genealogy of Greek urban space and underscores its significance (Καλαντίδης et al., 2023). These situated studies shed light on an important sociological argument that has influenced the evolution of geographical thinking regarding childhood (see Qvortrup, 1987; Alanen, 1988). The argument is that: children’s lives are not solely confined to institutional, domestic, and specially designed spatial environments, such as the school building, the child’s room and the playground, but are broadly articulated in the spaces of their everyday lives. To encounter and investigate children in the city, we may follow their traces in everyday life. In the urban environment, apart from the designated thematic corners tailored for the child, elements such as streets, public transportation, urban amenities, textures and materials of the built environment, shops, apartment complexes, neighbours, and various unremarkable objects and details within the urban space constitute the lived spaces of children in their neighbourhood (Figure 3). It is in these ordinary and common urban spaces that children’s coexisting everyday life unfolds.

Figure 3: Spaces of children’s everyday life in the neighbourhood

Source: Children’s photographs from the ethnographic research archive in Pagrati, in Καραμπίνη, 2023

Children’s geographies are shaped in the same spaces shared by the rest of the city’s residents, highlighting the dynamic and dual meaning of this coexistence. On one hand, the actions and the presence of children in public spaces reveal their spatial and social marginalization in the city. The spatial manifestations of public interest, driving urban redevelopment projects in the centre of Athens, primarily cater to tourists and passersbys, often neglecting the needs of residents in the city’s neighbourhoods. On the other hand, the coexisting everyday lives of children reveal connections and alliances they forge with one another, with parents, caregivers, neighbours, pets, or stray animals, all of which seek social acknowledgment and institutional support. These everyday intersections invite us to highlight common spacetimes in the city, thereby disrupting the existing spatial divisions and social categorizations.

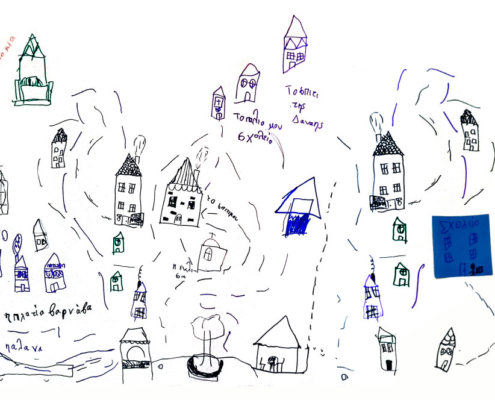

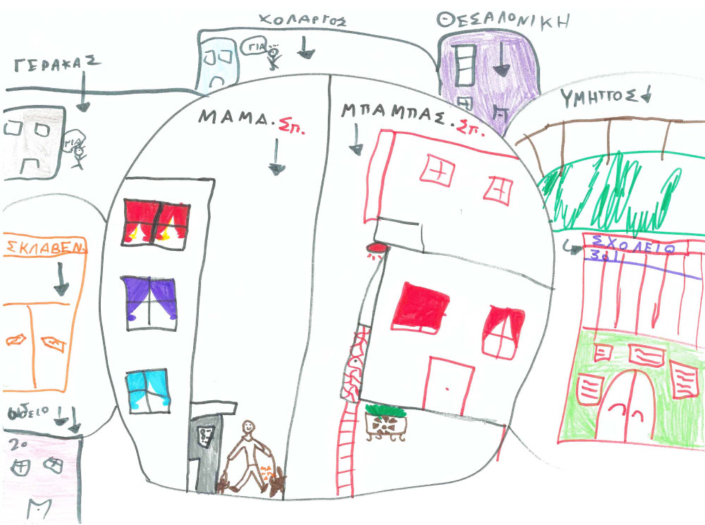

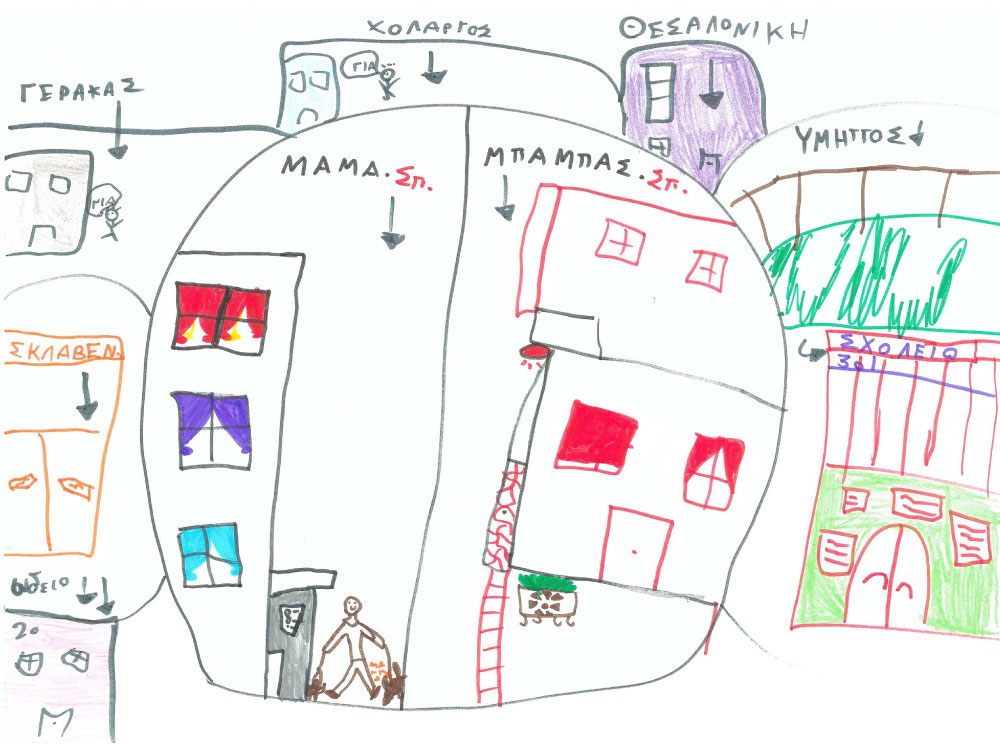

Children’s spatial mobility in the neighbourhood is largely centred around their homes. Contrary to dominant Western representations that associate the home with introversion and circular repetition (Fleski, 2000), children’s agency restores the social dimensions of domestic life. According to children’s mappings, home is conceptualized through the notions of housing, habitation, family and belonging (Figure 4). Marina mentions: “I’m going to draw a line and put dad’s here and mom’s here. We have very different things at mom’s and at dad’s. At mom’s we have apartment buildings and at dad’s we have a house with a yard”

Figure 4: The circle with my neighbourhood, Marina 8 years old

Source: From the ethnographic research archive in Pagrati, in Καραμπίνη, 2023

It is a multimodal place that activates multiple spatial practices in the neighbourhood: daily visits to the local market, social gatherings and children’s parties at homes, family rituals that bonds family members, and, of course, neighbouring. For children, neighbouring is a process of great importance, as it facilitates their familiarity with other residents. Their tendency to identify and map their neighbouring with other children, without necessarily getting to know each other personally, is particularly interesting (Figure 5). Helen says: “I am the only child living here. However, I have my friend Vassilis across the street. And further down my friend Christos […] At school no [we don’t talk]. On the balcony [only], when he goes out”

Figure 5: Everyday places, photograph of Eleni, 9 years old

Source: The ethnographic research archive in Pagrati, in Καραμπίνη, 2023

The traces that children shape as residents of Athenian neighbourhoods reflect their desire to live together and among their peers (Καραμπίνη, 2023: 89). In their mappings, this desire becomes evident as they capture those places and conditions of interaction and community building in the neighbourhood. Friends’ houses, squares, school, parks are described as places of socialization and action. The scale and details with which these spacetimes are defined are indicative of the significance that children attribute to them (Figure 6).

Figure 6: My home and my friend’s home

Source: The experiential workshop ‘Mapping the Neighbourhood” with children of the 1st grade of the 13th Primary School of Athens, 2020

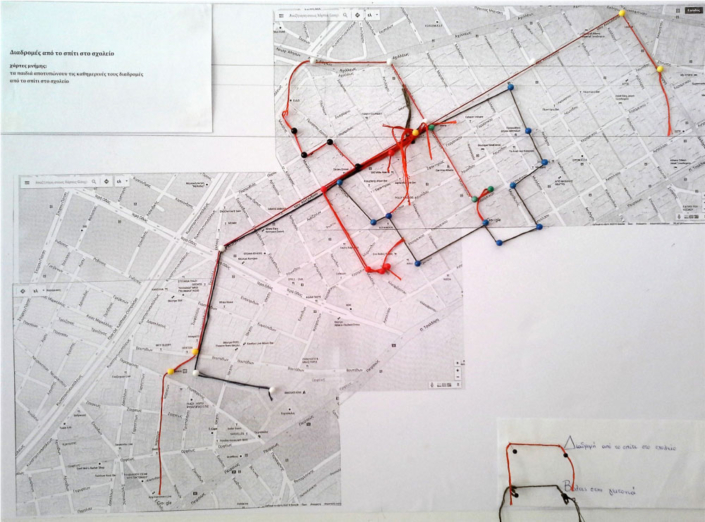

Through their daily movements in and out of the home, children produce meanings about the places they inhabit, highlighting the role of material space in this process (Christensen, James and Jenks, 2000). The spatial experiences of children living in Athens are defined by the typical apartment buildings, the dense urban construction, the shops, the monuments, the colours of the buildings, the local and the central events of the city – local markets and happenings. However, children’s sense of place is also co-shaped by images and experiences acquired by children in other material, imaginary and digital spaces. In their neighbourhood maps, spaces of the lived present intertwine with memories and representations that enrich and transform the meanings of the everyday. Consequently, what children perceive as a neighbourhood is constructed across multiple spaces and times (Καραμπίνη, 2024; Μίχα, 2020) (Figure 7). The scope, the boundaries and the structure of the place ‘here’ are constituted at different scales, from the global to the local (Massey, 2005).

Figure 7: Pins with different colours mapping family routes

Source: The educational workshop ‘Routes: something from elsewhere, something from everywhere’, 5th grade of full-day class, 64th Primary School of Athens, 2015-16, in Micha, 2019

Children’s daily routes in the city unveil their unique relationship with places in-between. Children demonstrate their systematic preference for places that mediate between two distinct spatial systems, as these places serve important emotional transitions. However, the value of in-between places does not solely lie in their functional role as transitional spaces. Rather, they are hybrid spaces that negotiate binary spatial systems, specifically challenging the constraints and conventions imposed by these systems, while also remaining open to new perspectives and contingencies (Soja 1996). Between real and imaginary, inside and outside, here and there, children cultivate their own cultures: playing alone or with other children, constructing imaginary and magical worlds, exploring space, sharing their secrets, and often trying to challenge adult rules (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Children appropriating the places in-between, in their daily routes in the city

Source: Outdoor teaching workshops in the neighbourhood of Exarchia, with children of the 1st grade of the 35th Primary School of Athens

In places in-between at the entrances and pilotis of the apartment buildings, the sidewalks or the balconies- they negotiate their socialization, while simultaneously negotiating rules and boundaries (Μίχα, 2023: 57). For these reasons they demonstrate a remarkable ability to identify and appropriate liminal places») -spaces that are ambiguous, unregulated, and not predefined by the adult order (Cloke and Jones, 2005) (Figure 9). These fluid geographies of children reveal an aspect of the city that lies dormant and untapped by dominant urban practices, thereby broadening our geographical perception (Soja 1996). Niki says: ” here is the opposite pharmacy (1) […] Here is our house (2), and here is the Police Station (3) and the road we pass (4) […] And over here is two more stores […] They are now open. One is a l-aw fi-rm (5) the other I don’t know what it is. I still haven’t figured it out. […] I would like to change this shop. Because I don’t know what it is. And if I changed it I would make it a playground, or a steakhouse – souvlaki (6) “

Figure 9: My neighbourhood, Niki 11 years old

Source: The ethnographic research archive in Pagrati, in Καραμπίνη, 2023

Focusing on children’s inventions and claims in urban studies

In their urban narratives, children do not merely list familiar and unfamiliar places or landmarks of Athens; rather, they offer a multi-layered perspective of the urban field, encompassing textures, smells, sounds, and action (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Τhe snowy neighbourhood of Exarchia

Source: The experiential workshop “Mapping the Neighbourhood” with children of the 1st grade of the 35th Primary School of Athens, 2019

This perspective reveals their complex and dynamic relationship with space and suggests different ways of reading the city; multi-sensory modes that take into account temporalities, emphasizing field conditions, such as seasons, weather or other phenomena, socio-political current affairs, as well as affective modes that involve personal and collective action in the interpretation of space (Figures 11a & 11b) .In their narratives, children interweave inner concerns with experiences in the neighbourhood with friends, in routine or unexpected situations. They describe the individual and collective worlds they create, the habits, actions, relationships and informal social rules they devise -and over time subvert- in their everyday coexistence (Seigworth and Gregg 2010). Within these worlds, play has a prominent role, serving as a means for children to continually expand their spatial boundaries and reinvent both familiar and unfamiliar spaces, thereby reshaping conventional spatial arrangements.

Figures 11a & 11b: Mahmoud draws his neighbourhood

Source: The educational programme ‘Landmark buildings of the Modernist architectural movement in Athens: a view around 3rd September – Patision axes (2020-21)’, https://elenakyla.wordpress.com

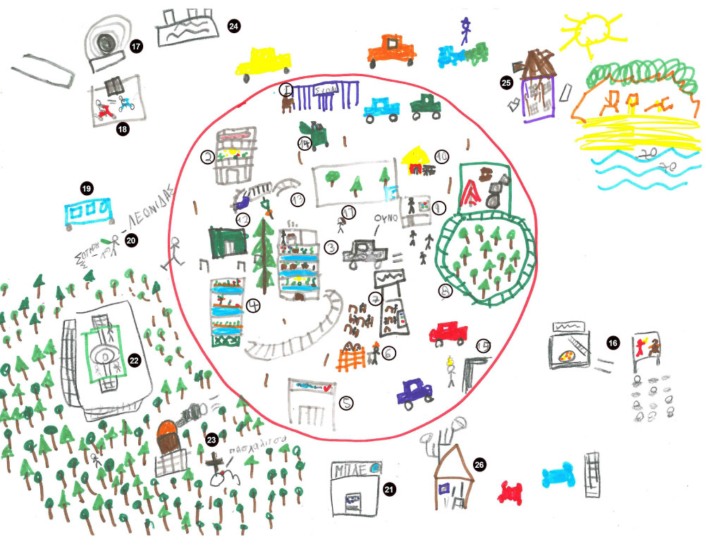

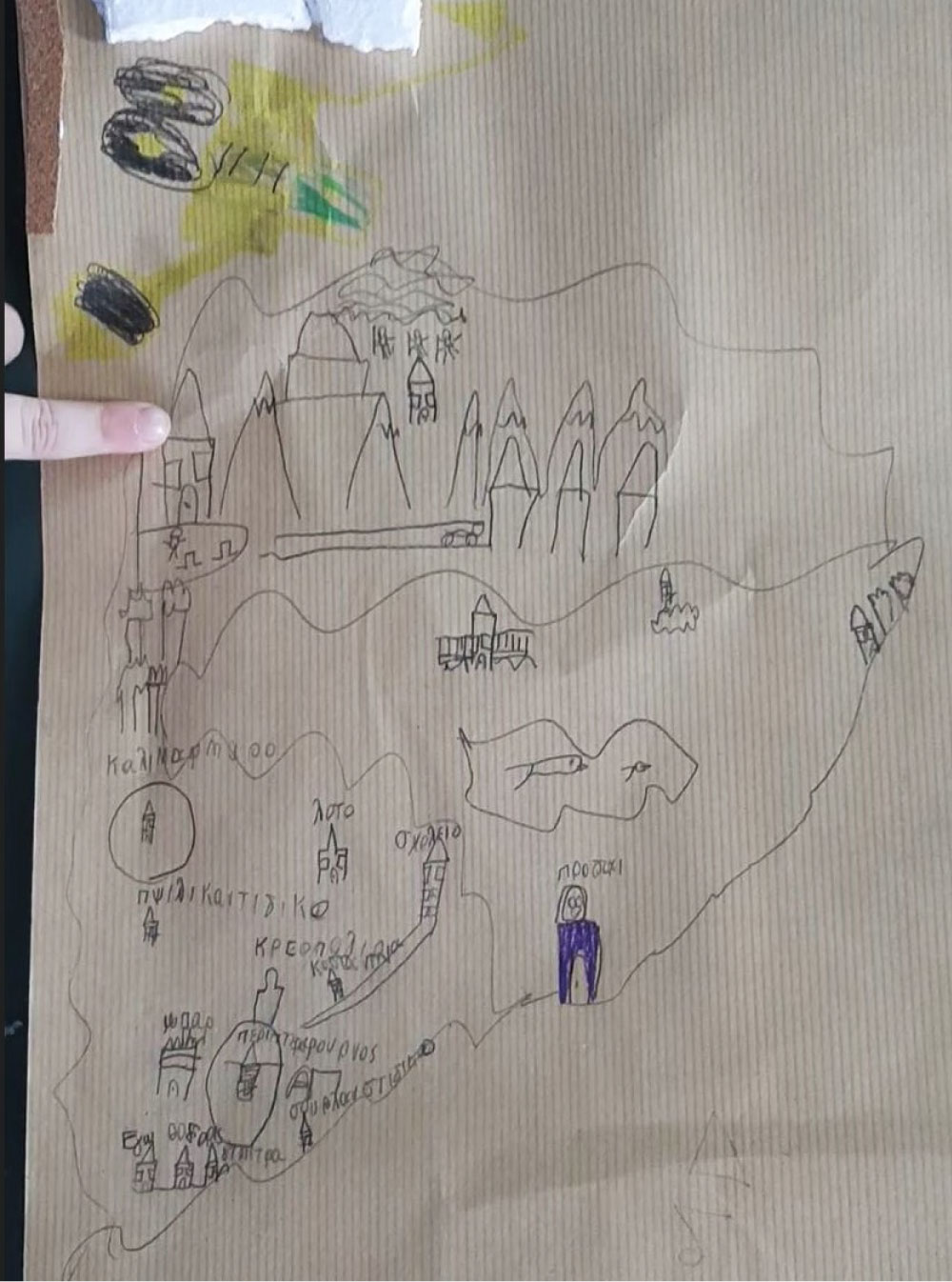

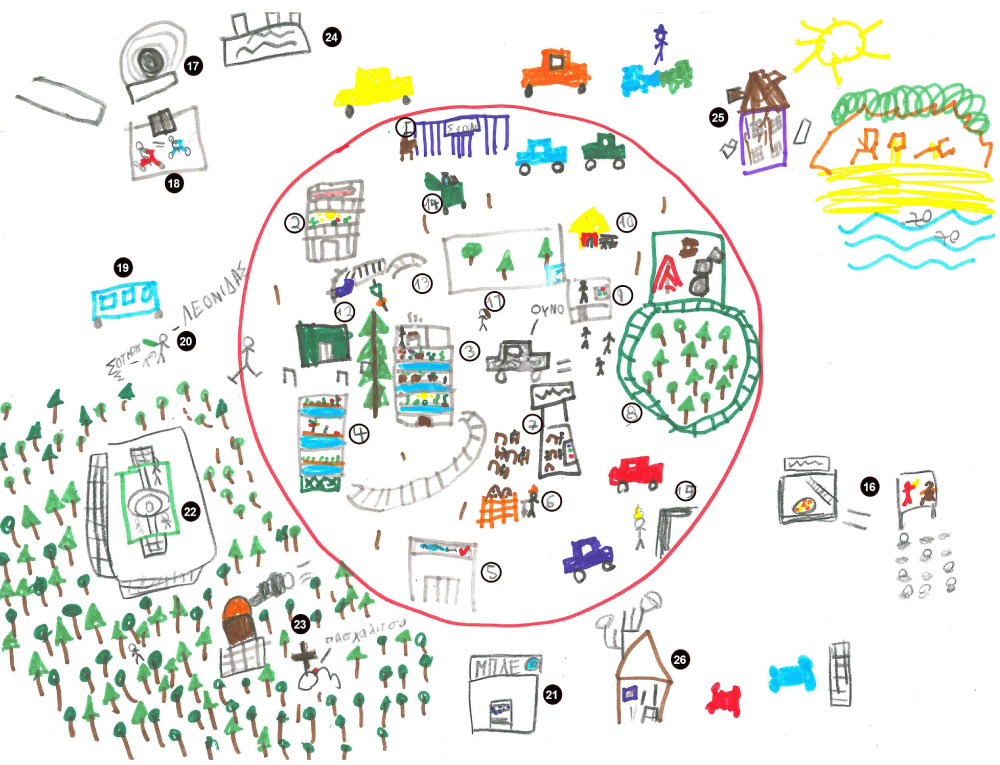

The systematic observation of children’s play in the neighbourhoods of Athens revises the established perception that children’s play is spatially restricted and defined. Children play everywhere and continuously throughout the urban space. The multifaceted nature of play brings into focus their ability to co-produce broader geographies in the city. Through play, they perform a process of producing and transforming spaces as they shape, reconstruct, and invent new spatialities (Figure 12). Children’s spatial inventions, such as hiding spaces, forts and haunted buildings, signify a deep connection to place, with substantial social ramifications for the collective life of the neighbourhood (Καραμπίνη, 2024). As documented in relevant research, children tend to care for and defend the play products: their own places, their friendships and their freedom (Χουϊζίνγκα, 1989). Building upon this understanding, we propose to approach the places that are woven by children during their play, not merely as areas accommodating children’s activity, but as contested spacetimes of everyday life. This view reveals to us that children express personal spatial readings and produce spatial rearrangements, thereby articulating their subjectivities in space. In other words, it highlights the political dimension of their action in the city. Alkis describes: Inside the circle we see (1) the School, (2) my friend’s M house, (3) our house, (4) grandparents’ house, (5) supermarket, (6) where the archaeological excavations take place, (7) the bar (ouzeri) “Sylvia”, (8) the Grove (Alsos), (9) the ice cream shop, (10) the kiosk, (11) the Messolonghi square, (12) the Youkali – cafe, (13) the playground, (14) a bin, (15) the hairdresser. Outside the circle is depicted (16) the cinema that became Lidl, (17) this is Kallimarmaro, (18) and this is X.’s bike and my bike that goes like a bullet, (19) the school-bus that takes us to the excursion, (20) Leonidas argues with Sotiris, (21) The Ble Telia (Blue Dot) – painting workshop, (22) this is football, (23) this is the observatory, at the observatory we buried a ladybug, (24) and the Acropolis, ( 25) and this is a haunted house. It was falling wood and it was near the Blue Dot. I’ll do it with a scratched number.

Figure 12: The circle with my neighbourhood’, Alkis 8 years old

Source: The ethnographic research archive in Pagrati, in Καραμπίνη, 2023.

For children, the spatial practices of play are intertwined with educational practices (Figure 13). The spaces and times of school, tutoring centres, educational outings are interconnected with those of their play and leisure activities. Their daily action forms a changing spatial grid that is rearranged as they grow up, move on to the next educational level, change their friendships and habits. Play and educational spaces interweave local nodes and networks in neighbourhoods, form peer communities, foster encounters with ‘otherness’ and activate the memory of place. Children and the everyday places they produce are living cells of historical time. The stories of the old residents who once acted in the same neighbourhoods, as well as the local customs and traditions, are spatialised through education, family and children’s communities, in institutional and informal ways, in children’s geographies. Mappings of children’s everyday actions reveal a multitude of cultural differentiations, dictated by nationality and religion, thereby showcasing the multiculturalism of Athens’ residents (Figure 14).

Figures 13-15: Figures from educational and experimental workshops

Children narrate their routes in the neighbourhoods of Athens, weaving together their personal movements, practices, desires, and concerns with the daily occurrences of the city. The contextual circumstances of the present –including socio-political developments and occasional events– impact their perception of their neighbourhood. Festivals, public holidays, strikes, but also the political management of critical issues such as the pandemic and the refugee crisis, reflected in the spaces of the neighbourhoods of the capital, are embedded in multiple ways in their elaborations (Figure 15). Children’s perspectives consciously articulate the “here and now” of their co-existence and claim their space in research, education and, more broadly, in the everyday life of the city.

[1] Urban Analysis Unit (URANU). It is a spatial unit / division of the urban tissue of large Greek cities based on the Census Tracts of ELSTAT. URANUs have an average population of 1,200 people.

[2] We refer in particular to William Bunge’s work in the Fitzgerald area of central Detroit (1973), where, after the 1967 riot, he, along with Gwendolyn Warren, Robert Ward and others, set up an inventive street university, the Detroit Geographical Expedition and Institute (DGEI), to organize geography courses for local children and teenagers and to develop participatory field research, through which spatial and social inequalities and racial discriminations, especially in the daily lives of children, were mapped. In the 1970s, a variety of further studies focused on children’s practices and movements in urban and rural settings (including Lynch 1977; Ward 1978; Hart 1979).

Entry citation

Karampini, Z., Micha, I., Vallindra, E. (2024) Children’s geographies in the neighbourhoods of Athens, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/childrens-geographies-in-athens/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.123

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Aitken St, Lund R and Kjørholt A (2007) Why Children? Why Now? Children’s Geographies 5: 13-14

- Alanen L (1988) Rethinking Childhood, Acta Sociologica 31(1): 53–67

- André I, Carno A, Abreu A, Estevens and Malheiros J. (2012) Learning for and from the city: the role of education in urban social cohesion. Belgeo 4. URL: http://belgeo.revues.org/8587

- Bunge W (1971) Fitzgerald; Geography of a Revolution. University of Georgia Press

- Christensen P, James A and Jenks C (2000) Home and movement. Children constructing ‘family time’. In Holloway SL & Valentine G (eds.) Children’s Geographies: Playing, Living, Learning London and New York: Routledge, pp. 120-134

- Cloke P and Jones O (2005) ‘Unclaimed territory’: childhood and disordered space(s). Social & Cultural Geography 6(3): 311-333. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360500111154

- Crampton JW (2001) Maps as social constructions: power, communication and visualization. Progress in human Geography 25(2): 235-252

- Del Casino VJ and Hanna SP (2005) Beyond the ‘binaries’: A methodological intervention for interrogating maps as representational practices. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 4(1): 34-56

- ΕΚΚΕ-ΕΛΣΤΑΤ (2015) Πανόραμα Απογραφικών Δεδομένων 1991-2011. Διαδικτυακή εφαρμογή πρόσβασης και επεξεργασίας απογραφικών δεδομένων (https://panorama.statistics.gr/).

- Felski R (1999) The Invention of Everyday Life. New Formations, 39(1): 15-3

- Gayet-Viaud C, Rivière Cl & Simay Ph (2015) Les enfants dans la ville. Métropolitiques 13. URL: https://www.metropolitiques.eu/spip.php?page=print&id_article=812

- Gruenewald D (2003) The Best of Both Worlds: A Critical Pedagogy of Place. Educational Researcher 32(4): 3-12

- Harley JB (1989) Deconstructing the map. Cartographica: The international journal for geographic information and geovisualization 26(2): 1-20

- Hart R (1979) Children’s Experience of Place. Irvington

- Holloway SL & Valentine G (2000) (eds.) Children’s Geographies: Playing, Living, Learning London and New York: Routledge

- Καλαντίδης Α, Μαντουβάλου Μ, Μίχα Ε και Στρατηγάκη Μ (επιμ.) (2023) Έμφυλες προσεγγίσεις στη μελέτη της πόλης. Αθήνα: Νήσος. ISBN: 9789605891763

- Καραμπίνη Ζ (2023) Καθημερινές πρακτικές και νοηματικές παραγωγές της γειτονιάς μέσα από τις γεωγραφίες των παιδιών στο Παγκράτι. Διδακτορική Διατριβή, Αθήνα: Εθνικό Μετσόβιο Πολυτεχνείο

- Καραμπίνη Ζ (2024) Υφαίνοντας τόπους της παιδικής ηλικίας στην πόλη. Στο: Μίχα Ε (επιμ.) Για μια χωρική ματιά στην εκπαίδευση, Αθήνα: Gutenberg, σ. 213-242

- Katz C (1994) Textures of global changes: eroding ecologies of childhood in New York and Sudan. Childhood: A Global Journal of Childhood Research 2(1-2):103–110

- Kitchens J (2009) Situated pedagogy and the situationist international: Countering a pedagogy of placelessness. Educational Studies 45(3): 240-261

- Lynch K (1977) Growing up in Cities. MIT Press – UNESCO

- Maloutas, T. Spyrellis, S. (2019) Inequality and segregation in Athens: Maps and data, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. DOI: 10.17902/20971.92

- Massey D (2005) For space. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage

- Micha I (2019) Children’s Everyday Flows and Networks in the Neighborhoods of Athens. In: Micha I & Vaiou D (ed.) Alternative takes to the city. Wiley-ISTE, pp. 81-100

- Μίχα Ε (2020) Συνομιλώντας για την πόλη με τα παιδιά. Στο Τσουκαλά Κ & Γερμανός Δ (επιμ.) Παιδική χωρική αφηγηματικότητα, πόλη – παιχνίδι – εκπαίδευση. Αθήνα: Επίκεντρο, σ. 423-438.

- Μίχα Ε (2023) Ανάμεσα στο ιδιωτικό και στο δημόσιο: θεωρητικές διχοτομίες και καθημερινές διαπραγματεύσεις. Στο: +oikismos_ 12 κείμενα για τον δημόσιο χώρο στο πλαίσιο της ομώνυμης εικαστικής παρέμβασης στον Συνοικισμό Χαλανδρίου 2019-2023 (επιμέλεια και σχεδιασμός Παπαρούνης Μ). Αθήνα: Futura, σ. 54-58

- Μίχα Ε (επιμ.) (2024) Για μια χωρική ματιά στην εκπαίδευση, Αθήνα: Gutenberg, ISBN: 978-960-01-2535-1

- Morgan J (2000) Critical pedagogy: the spaces that make the difference. Culture & Society 8(3): 273-289

- Qvortrup J (1987) Introduction. International Journal of Sociology, 17(3), 3-37

- Seigworth GJ and Gregg M (2010) An inventory of shimmers. In Gregg & Seigworth GJ (Eds.) The affect theory reader. Duke University Press, pp.1-28

- Smith GA (2002) Place-based education: learning to be where you are. Phi Delta Kappan, 83(8): 584-594

- Soja EW (1996) Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and other Real-and-Imagined Places. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd

- Ward C (1978) The child in the city. Pantheon Books

- Χουιζίνγκα Γ (1989) Ο Άνθρωπος Και Το Παιχνίδι (Homo Ludens). Αθήνα: Γνώση