The impact of the crisis on food retailing in Athens

Faka Antigoni|Skordili Sofia

Economy, Quartiers, Social economy

2018 | Aug

At national level, food is the most important spending category for households amounting to 20.7 per cent of their average monthly expenditure. For the poorest 20 per cent of them, food expenditure absorbs almost 1/3 of their disposable income (32.1 per cent) (ΕΛΣΤΑΤ, 2017). The drastic reduction in household disposable income, 26.0 per cent on average, led to an even greater decline in domestic food consumption. The overall decline was 29.4 per cent, over the period 2009-2014 (Χαραλαμπάκης, 2017). However, the rate of change varies considerably among food categories and retail format.

Which food categories, from what type of retailers?

The impressive shrinkage of the groceries market is accompanied by major changes in consumer patterns. Consumers shop smaller quantities and cheaper food categories. Furthermore, during the crisis, the large grocery chains have increased their attractiveness to consumers and gained new market shares. Consumer spending on food categories which contribute decisively to a balanced diet have declined significantly over the period 2009-2016 (ΙΕΛΚΑ, 2017). these include lamb and goat meat (-45 per cent), fish (-33 per cent), fruit (-23.5 per cent) and raw milk (-15 per cent). At the same time, consumption of categories of cheaper food products, such as pulses (+ 17.8 per cent) and private label products has grown rapidly (ΙΕΛΚΑ, 2017).

During the 2010-2017 period, the General Index of Retail Trade Turnover (excluding fuels and lubricants, base year in 2010 = 100), fell to 73.7 points. On the other hand, the index for category “big food stores” has followed smoother downward trend and dropped to 82.4 points (graph 1) (ΕΛΣΤΑΤ, 2018). In particular, within the category of big stores, smaller chains and self-service shops experienced a significant reduction in turnover, while top corporate chains saw minor declines or even increased sales. It is indicative that the two leading [1] chains in 2016 posted aggregate sales of € 4.3 billion compared to € 4.0 billion the year before. Similarly, the country’s larger discount grocery store saw a spectacular increase in sales over the first half of 2016, by 11.6 per cent, compare to the same period in 2015 (Καθημερινή, 20/08/2016).

Graph 1: Evolution of the Turnover Index in selected retail sectors, 2009-2017

During the crisis, the major chains have reinforced their market position. They achieved this : a) by buying out competitive retailers; b) by adapting the product mix and pricing policy to the new context, i.e. by market offers and introduction of new, cheaper, usually private label, products; and (c) by applying new network development strategies in the Athens Metropolitan Area.

The new geography of the leading grocery chains in Athens

During 1960-2010, a period of uninterrupted growth in food consumption, the large and cohesive Athens Metropolitan Area market was the prime target for expansion by grocery retailers. That market has retained its attractiveness during the crisis.

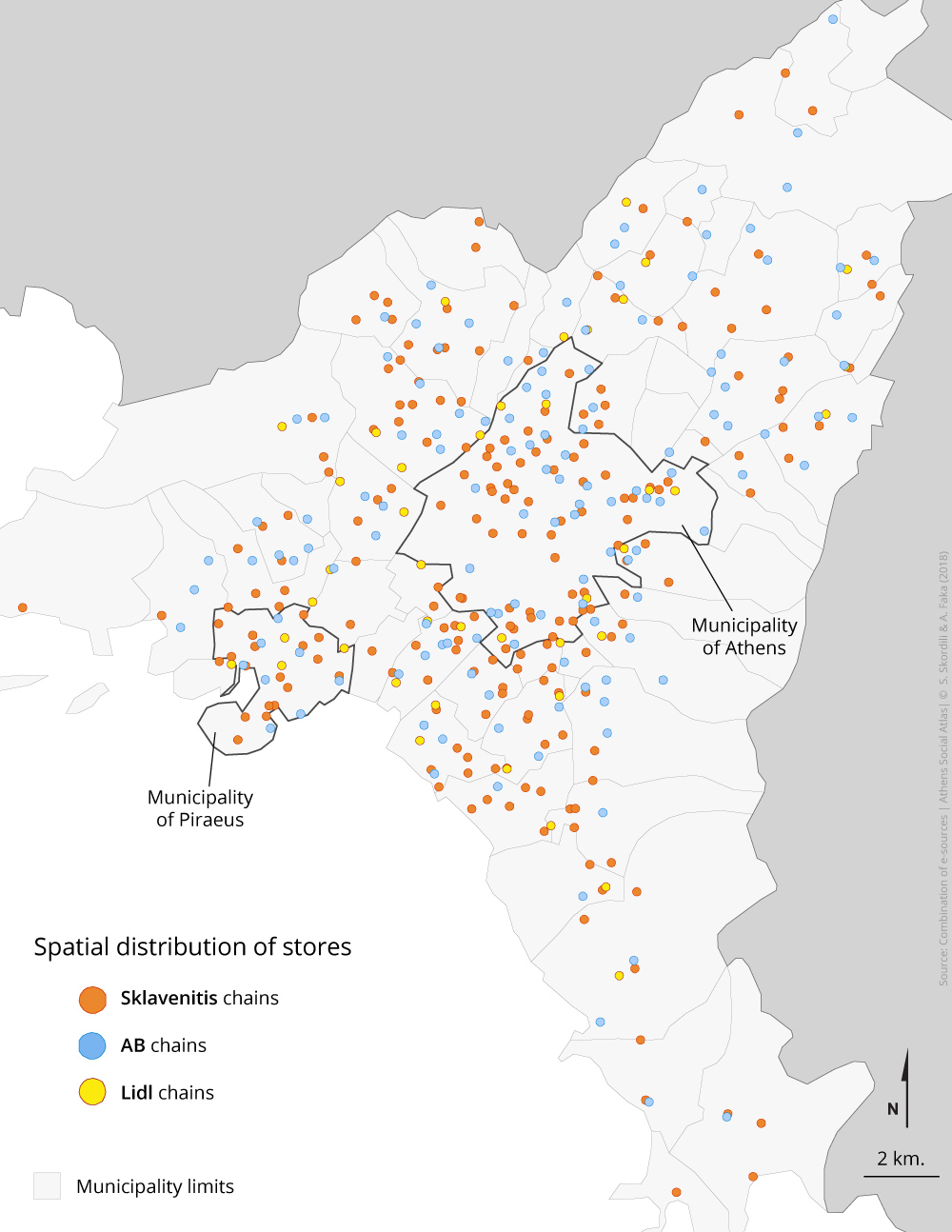

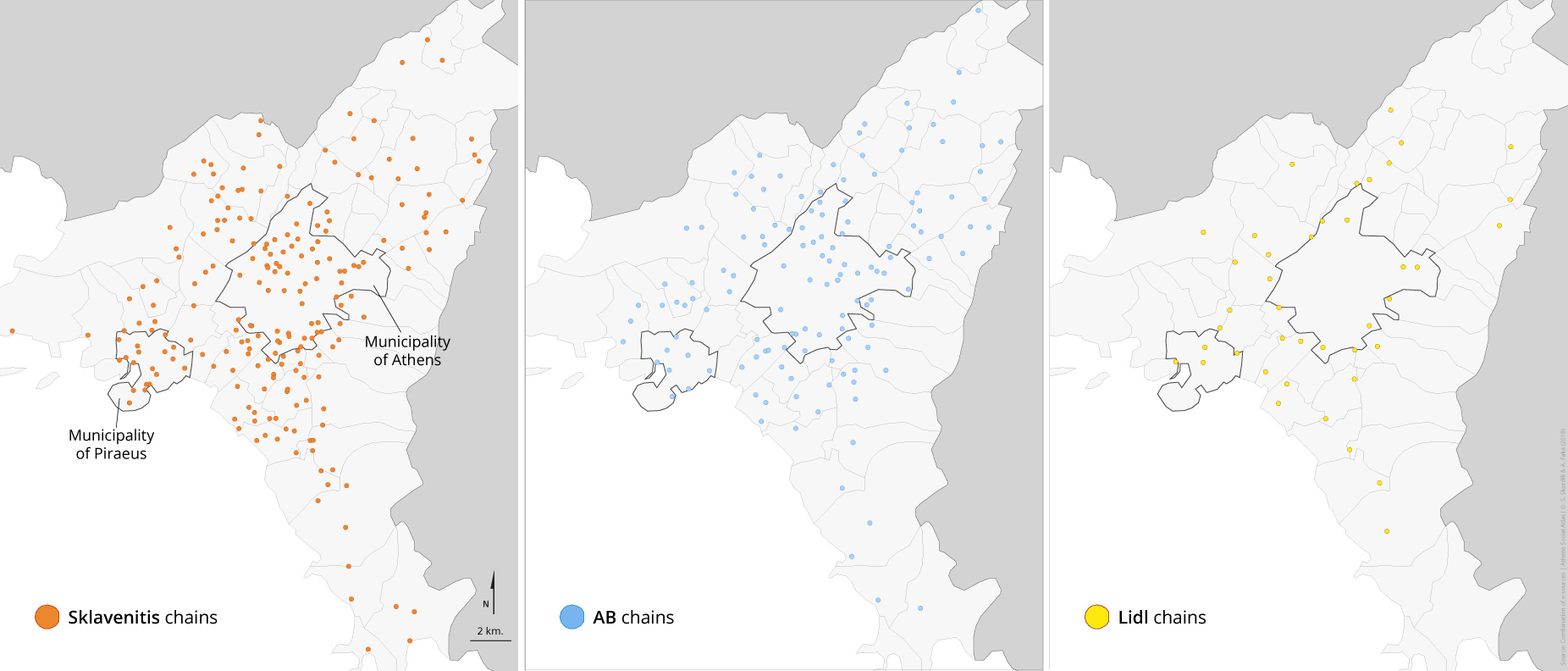

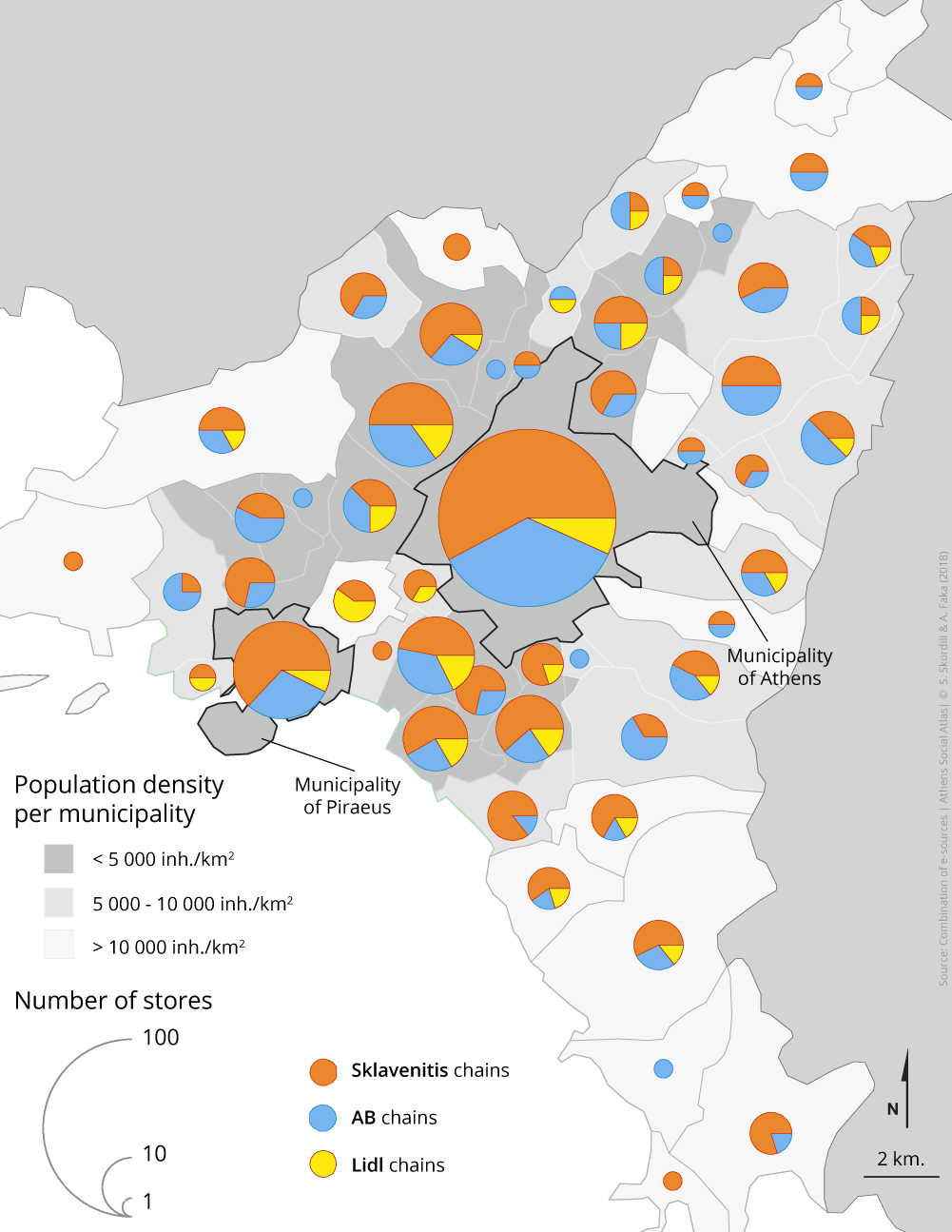

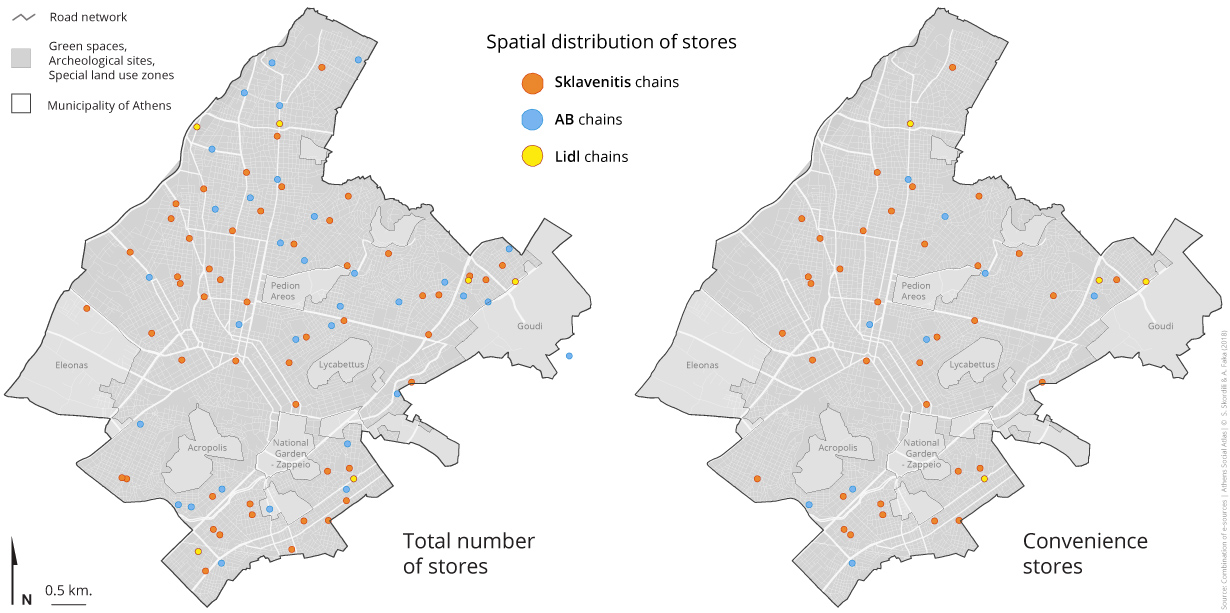

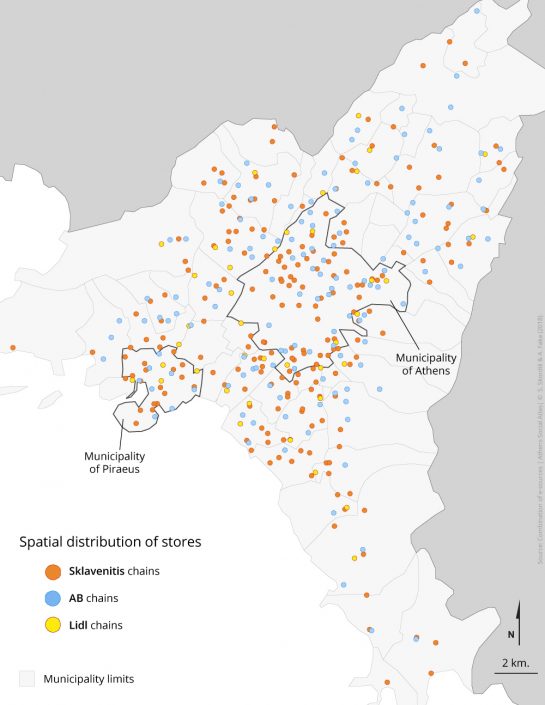

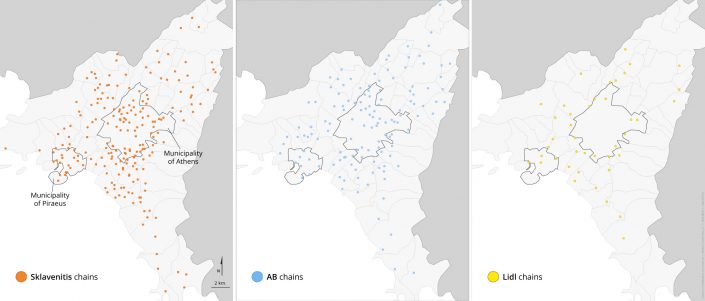

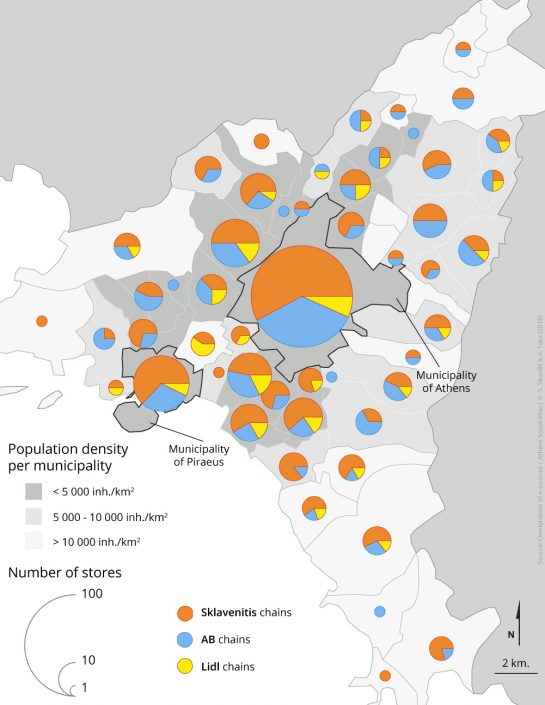

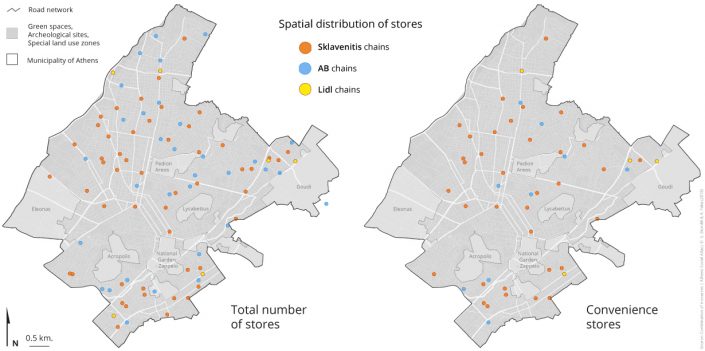

From 2000 to 2010, top chains boosted their presence in the city by creating new large stores along the major road network and on the high streets of the rapidly growing suburbs . When the first signs of the crisis emerged, major retailers began to develop dense networks of small convenience stores in every municipality of the capital city. At present, the three top chains have established a strong presence in Athens, with slight variations between them (maps 1α & 1β). Their presence is particularly strong in the densely populated areas of the central municipalities of the conurbation. These neighborhoods offer exposure to a large customer base, as well as low logistics cost (map 2) (Pothukushi and Kaufman, 1999).

Map 1α: Spatial distribution of the three leading grocery chains in the Athens Metropolitan Area, 12/2017

Map 1b: Spatial distribution of the three leading grocery chains in the Athens Metropolitan Area, 12/2017

Map 2: Spatial distribution of the three leading grocery chains and population density per municipality in the Athens Metropolitan Area, 12/2017

It is important to underline that the significant variations in the number of stores maintained per municipality by the three top chains, Sklavenitis, AB and Lidl, do not reflect similar variations in the volume of sales. As evidenced by the distribution of convenience stores in the municipality of Athens this is largely attributed to the development of different store formats (map 3). Two leading chains have developed dense networks of convenience stores (200-400 m2), while the third one (Lidl) bases its expansion on supermarket stores (800 to 1500 m2).

Map 3: Spatial distribution of the total number of stores and convenience stores of the three leading grocery chains in the municipality of Athens, 12/2017

Convenience stores have high footfalls since they fit new consumer demands molded by the crisis. The prevailing shopping pattern involves more frequent purchases of cheaper food in smaller quantities from destinations in close proximity to the family residence (Lowe and Wringley, 2010). These stores pose the greatest threat to local grocery retailing, since they have become a collective destination for everyday shopping, not just for food products. Several new regulations put in place after the recently implemented market liberalization scheme, such as the extension of shopping hours and the licence tosell freshly baked products in small stores, have increased their attractiveness. As a result, their number has been steadily increasing over the last five years.

Contrasting trends in independent food retailers

As shown in graph 1, the Turnover Index of the category ‘Food – Beverage – Tobacco’, which includes independent (small) retailers selling food exclusively or together with other goods, has collapsed to 66.5 points, well below the equivalent index of large food stores (82.6) and the Index of General Retail Trade (73.7) (ΕΛΣΤΑΤ, 2018). More independent retailers selling food have gone out of business than retailers in any other trade sector. According to data published by the Institute of Commerce and Services, independent food stores comprised 5.8 per cent of the total number of independent shops in Athens, in 2014. Two years later, although the decline of all independent retail outlets was fast, their participation had fallen to 5.3 per cent (ΙΝΕΜΥ-ΕΣΕΕ, 2016).

However, a closer look at the statistics, as well as at the geographical distribution of shops in Athens, reveals that independent food retailers are not developing in homogenous ways.

A neighborhood in focus

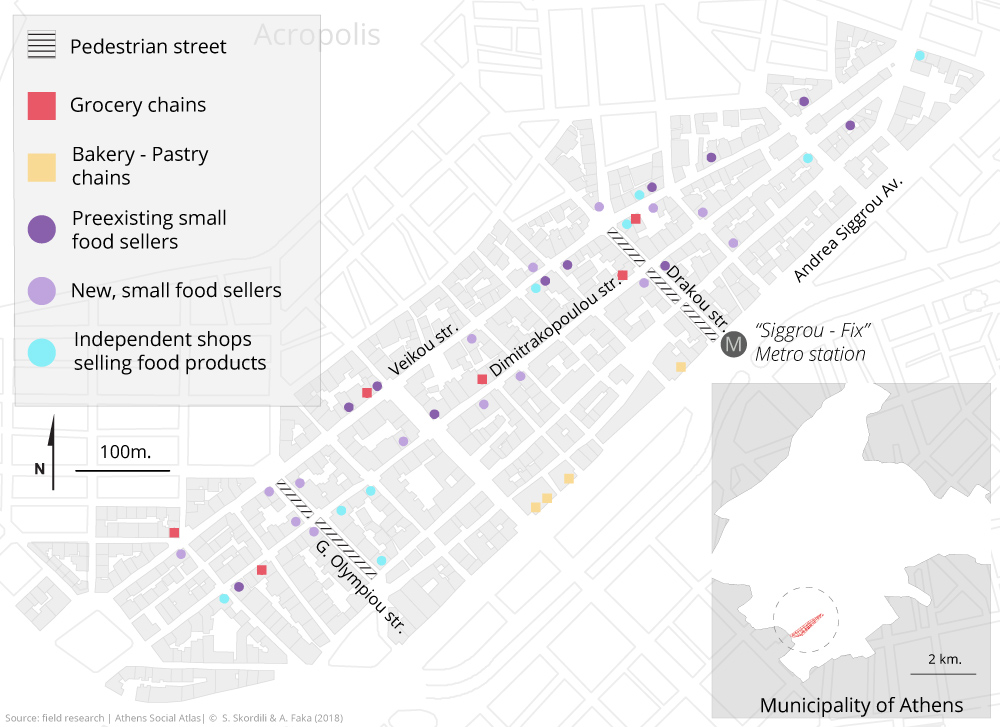

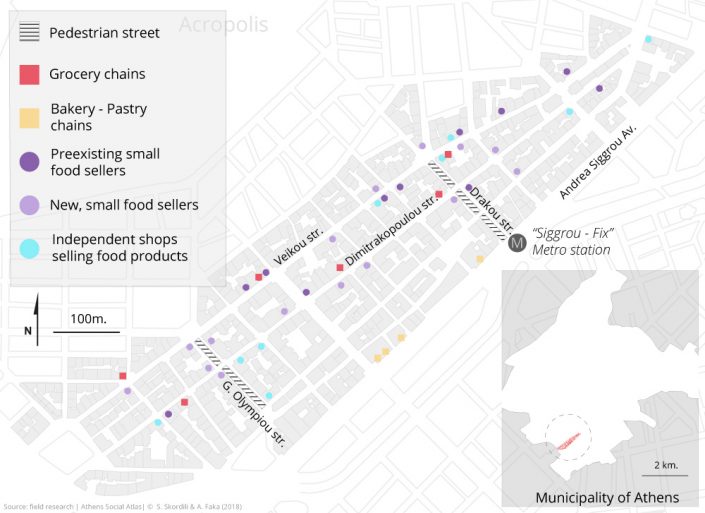

A recent (Oct-Dec 2017) door-to-door survey covering the Koukaki area (Syngrou – Chatzichristou – Veikou – Sikelias streets), revealed that food retailing is thriving in that neighborhood and, in fact, it is more prominent than any other retail trade. In spite of the large number of abandoned shops (photo 1) there were 45 active food retailers of various types and sizes (map 4a).

Photo 1: Abandoned shops in a row, 12/2017

Map 4a: Food retail shops in the Koukaki neighbourhood, 11/2017

As shown in the map there is an obvious locational preference of food retailers for highly visible and easy to access points: along the two main traffic routes, Veikou Str. and Dimitrakopoulou Str. andalong the two pedestrian streets, Drakou Str. and Georgaki Olympiou Str.

Map 4b: Food retail shops per category in the Koukaki neighbourhood, 11/2017

Ten out of the 45 stores, a significant number for such a small neighborhood, belong to large grocery and bakery chains (map 4b). Presumably, their share of local food sales is much higher than the share of the other stores. These stores attract large numbers of consumers and are in need of frequent deliveries, so they pose a considerable extra burden to the already high traffic load of the area. Due to the profound lack of big commercial spaces at the neighborhood level, several of these stores have been located in small and unsuitable shops (photo 2). Due to their small size they are obliged to limit the range of the products on offer below the 3,000-5,000 product codes that are usually available in a typical convenience store (Lowe and Wringley, 2010).

Photo 2: Food chain store developed in two separate stores on either side of a block of flats entrance, 12/2017

Nevertheless, next to the powerful retailers, thirty-five independent retailers are active and resist the uniformity and standardization imposed by the big retailers. Independent shops do not constitute a homogeneous group. In fact, they differ substantially in their qualitative features and in their dynamics. Nine of those retailers are specialized independent stores (wine merchants, corner shops) that sell a selective range of food products, covering the times of day when grocery stores are closed.

The remaining 26 independent shops only sell food. Ten of these are traditional independent bakeries, greengrocers, grocers, butchers and fish mongers. These traditional shops, along with the weekly farmers’ market of the neighborhood, continue to appeal to loyal customers, offering a range of services that differentiate them from supermarkets (friendly service, home delivery, informal credit arrangements etc.). They emphasized the domestic origin of their products during the crisis, as opposed to the mainly imported food found in the shelves of corporate retailers. It must be noted that the bold national symbols on the facades of these stores show that the national origin has outgrown the local during the crisis (photo 3) (Σκορδίλη, 2016).

Photo 3: Butcher shop, 12/2017

The last and larger category (16 out of a total of 36 stores) are either brand new initiatives, entering the business during the crisis, or traditional stores that have been recently restructured and repositioned in the market. The restructuring is usually related with the entry of the younger generation in the family business. These food specialty stores, known as ‘new-grocery stores’, have made their presence felt in every Athenian neighborhood during the crisis. Due to the low needs for initial capital and their familiarity with food, several young men and women who face difficulties in entering the labour market, as well as older people experiencing or threatened by unemployment, took the initiative to be involved in micro food retailing.

The majority of those establishments are elegant small shops with well-designed signs and stylish decoration (photos 4 & 5). They have emerged as meeting and socialization points for residents of the wider area who share common interests in quality nutrition, local products and support small scale activities.

Photo 4: New store selling fruits, vegetables and fresh juices, 01/2018

Photo 5: New store selling local grocery products, 01/2018

Specialty food retailers: a crucial node in short supply chains

The potential impact of these new food specialty retailers could be significant. Their benefits is not limited to reducing unemployment and offering food of high nutritional value. Their integration to short agri-food supply chains may well have a decisive impact on the survival of thousands of independent farmers and local food producers. Specialty retailers can serve as an alternative market channel for small-scale producers that are blocked by the established networks of corporate retailers. They may connect producers with distant consumers as they are able to convey information about the origin, the production process and the nutritional value of food to the consumers while, at the same time, they may communicate the observations and special demands of consumers to the producers (Renting et al., 2003).

However, the protracted social and economic crisis does not facilitate the inclusion of small food retailers in short supply chains. In the context of limited funds and low consumer demand, their owners are forced to limit their visits to rural areas in search of new suppliers. Hence, a big number of them has already joined wholesale networks. For the same reasons, they are pushed to limit the range of the products offered and are extremely hesitant to extend their business to new high added value activities, such as cooking seminars or online sales. Therefore, in practice, the core features of that retail format have been distorted and specialty retailers are losing all the direct and indirect advantages they can gain from their participation in short supply chains (Σκορδίλη, 2016).

Small-scale food retailing is not an outdated retail format but a significant destination for complementary shopping. Currently, an increasing number of cities all over Europe and North America support small-scale independent food retailers with policies in their Municipal Urban Food Plans (Morgan, 2012). The city of Athens has to take similar action without further delay, in order to enhance economic diversity, to link the city with its rural hinterland and to improve the nutrition of its residents.

[1] Fluctuations at the top of the hierarchy of large supermarket chains are often. During the first half of 2018, the three leading chains, in hierarchical order, Sklavenitis, AB and Lidl, dominate the food retailing sector. Their performance in the key activity measurements is the following: annual turnover (balance sheet estimates 31/12/2017), 2.2, 2.1 and 1.0 billion euros; number of employees (full-time and part-time), 23.000, 14.000 and 5.500 employees; number of stores (small and larger) 550, 370 and 220 respectively (data by multiple sources, mainly, FPress 06/01/2018).

[2] All photographs included in this article are taken by the authors

Entry citation

Faka, A., Skordili, S. (2018) The impact of the crisis on food retailing in Athens, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/food-retailing-in-athens/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.83

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- ΕΛΣΤΑΤ (2017) Έρευνα Οικογενειακών Προϋπολογισμών 2016. Δελτίο Τύπου 11/10/2017. Available from: http://www.statistics.gr/documents/20181/f692a045-65fc-40af-96c8-bfdb073ecbea (ημερομηνία πρόσβασης 24 Φεβρουάριος 2018).

- ΕΛΣΤΑΤ (2018) Εποχικά Διορθωμένος Δείκτης Κύκλου Εργασιών στο Λιανικό Εμπόριο (προσωρινά στοιχεία) 01/00-01/18. Available from: https://www.statistics.gr/statistics/-/publication/DKT39 (ημερομηνία πρόσβασης 30 Μάρτιος 2018).

- ΙNEMΥ – ΕΣΕΕ (2017) Ετήσια Έκθεση Ελληνικού Εμπορίου 2016. Ινστιτούτο Εμπορίου & Υπηρεσιών της Ελληνικής Συνομοσπονδίας Εμπορίου & Επιχειρηματικότητας. Available from: http://www.inemy.gr/Portals/0/EasyDNNNewsDocuments/618/00_Kef_2016.pdf (ημερομηνία πρόσβασης 22 Φεβρουάριος 2018).

- ΙΕΛΚΑ (2017) Μείωση της Δαπάνης των νοικοκυριών σε είδη παντοπωλείου αλλά αύξηση ως ποσοστό των συνολικών αγορών. Δελτίο Τύπου 17/10/17. Available from: http://www.ielka.gr/?p=2289 (ημερομηνία πρόσβασης 20 Φεβρουάριος 2018).

- Η Καθημερινή (2016) Η ύφεση χτυπάει τα νοικοκυριά, που περικόπτουν την κατανάλωση τροφίμων. Αθήνα, 20ο Αύγουστος. Available from: http://www.kathimerini.gr/871634/article/oikonomia/ellhnikh-oikonomia/h-yfesh-xtypaei-ta-noikokyria–poy-perikoptoyn-thn-katanalwsh-trofimwn.

- Σκορδίλη Σ (2016) ‘Νέες’ πρωτοβουλίες στον αγρο-τροφικό τομέα: Ευκαιρίες και εμπόδια για ανθρωποκεντρική και ισόρροπη χωρική ανάπτυξη. Στο: Λαμπριανίδης Λ, Καλογερέσης Θ, και Καυκαλάς Γ (επιμ.), Χωρική ανάπτυξη και ανθρώπινο δυναμικό: νέες θεωρητικές προσεγγίσεις και η εφαρμογή τους στην Ελλάδα, Αθήνα: Κριτική, σ 528.

- Χαραλαμπάκης Ε (2017) Πόσο έχει επηρεάσει η κρίση την οικονομική κατάσταση των ελληνικών νοικοκυριών; Μια συγκριτική ανάλυση των δυο κυμάτων της έρευνας HFCS. Οικονομικό Δελτίο Τράπεζας της Ελλάδος 45: 37–54.

- FPress (2018) SuperMarket: Μάχη γιγάντων για το καλάθι. Αθήνα, 8th July. Available from: http://www.fpress.gr/epixeiriseis/story/54551/supermarket-maxi-giganton-gia-to-kalathi.

- Lowe M and Wrigley N (2009) Innovation in retail internationalisation: Tesco in the USA. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, Taylor & Francis 19(4): 331–347.

- Morgan K (2012) The rise of urban food planning. International Planning Studies, Taylor & Francis 18(1): 1–4.

- Pothukuchi K and Kaufman JL (1999) Placing the food system on the urban agenda: The role of municipal institutions in food systems planning. Agriculture and Human Values 16(2): 213–224.

- Renting H, Marsden TK and Banks J (2003) Understanding alternative food networks: exploring the role of short food supply chains in rural development. Environment and planning A, SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England 35(3): 393–411.