Gazochori: The History of a Neighbourhood (1857–1980)

Bournova Eugenia|Stoyannidis Yannis

History, Quartiers

2018 | Dec

Birth of a Neighbourhood

The Athens gasworks was established in 1857 by royal decree of King Otto, which granted French businessman François Théophile Feraldi the right to establish and operate the gasworks.

It was the first gasworks in the city of Athens and all of Greece and it quickly became an integral part of life in the capital, as it made street illumination possible and transformed everyday life in the city; the new gas streetlights gave those who were out in the city at night an improved sense of security. However, the biggest change anticipated with the coming of gas lighting was European splendour, which appears to have been coveted by part of the population of Athens from the mid-19th century onwards (Newspaper Skrip/ Σκριπ 25 December 1895).

Following the construction of the gasworks, which began in 1857 and continued for almost a century with the gradual addition of various annexes, unlicensed buildings began to spring up around it, forming the neighbourhood of Gazochori (Στογιαννίδης & Χατζηγώγας 2013: 53). As evidenced by its name—from the Greek gazi for gas and chorio for village—the settlement was formed after the gasworks began operations. In 19th and early 20th century sources, the neighbourhood is referred to sometimes as Gazochori and sometimes as the Aeriofotos neighbourhood or simply Fotaerio [1].

Before the founding of the gasworks, the wider area (Gazochori – Votanikos – Rouf) was out of the city limits and was mostly covered by fields and marshes. Indeed, an 1852 map shows the area west of Omonoia Square and north of Pireos Street to be practically uninhabited and deserted. Almost 20 years later, a 1875 map shows the gasworks and the area’s first buildings

Map 1: Map of Greece: Sheet 10, Athens plan, Division of Greece in Nomoi, Eparchies and Demes, 1852, (ΕΛΙΑ/ΜΙΕΤ)

Map 2: “Athens Town Plan of Athinai (Athens), Geographical Section General Staff No 4457, War Office 1944 (ΕΛΙΑ/ΜΙΕΤ)

Refugee Populations and Communicable Diseases

The name Gazochori was used by the daily press as early as 1885, with the area described as a hotbed of fevers, meningitis and typhus ( Newspaper To Asty/ Το Άστυ 29 December 1885). ). Indeed, at their 1900 conference, the Athens Medical Society referred to the so-called “epidemic of Gazochori” that took place during 1885-1886 and described a “malignant convulsive fever” which struck mostly children in the neighbourhood, which, it is stressed, featured “marshy areas”.

Addressing politicians and military officials, a satirical quatrain from the period says:

|

Tell them that there’s thousands dying in Gazochori Tell them that those horrid taxes still remain Tell them that the day has come, that is the worry, For Athens too the Spanish cholera to obtain (Ασμόδαιος 25 December 1885). |

In 1906 and 1916, the smallpox epidemics also claimed numerous victims in Gazochori ( Newspaper Empros/ Εμπρός 30 January 1906). The absence of an organised prevention and treatment system and the state’s lack of preparedness against diseases (Bournova, Garden, 2014) led the poor and the working class to seek practical solutions. Following the instructions of the neighbourhood’s midwives, residents would take their children that suffered from respiratory diseases to the base of the gasworks’ chimneys to have them inhale the “therapeutic” properties of the coke fumes (Στογιαννίδης, 2015: 115-116). Those suffering from tuberculosis would spend summers camping at Mount Penteli (Στογιαννίδης, 2016:382-404).

For several decades, the neighbourhood served as a receptor for newly arriving immigrants and refugees. In 1897, refugees from Crete settled in Gazochori ( Newspaper Empros/Εμπρός 28 November 1897). The arrival of refugees from Asia Minor increased the average household size, contributing to further deterioration of public and private hygiene:

| “…in the area of the gasworks, between Pireos Street and the Poulopoulos factory. Behold a new hell, practically within the capital, a horrible hell, which began in 1919 and is not ending. There are 325 families, Greeks from Russia and Pontus, that have settled in a large yard by the gasworks. They have built tiny houses, similar to those in Skopeftirio and in Dourgouti, at their own expense, but they can no longer live and sleep in them. Amid the neighbourhood there are two warehouses, and 35 families are housed—or, rather, are being murdered—there. Here too the few lavatories are insufficient, overflowing, and stench and death come from all sides. The neighbourhood’s residents are in anguish, and those closest have lost their patience and their health. They seem, inside the yard, as convicts and exiles, away from the lives of other people.”

(Ελεύθερον Βήμα, 20 Σεπτεμβρίου 1928). |

Increased levels of pollutants emitted by the gasworks added to the wretchedness in which the area’s working class already lived. On 15 June 1931, Stefanos Stefanou, journalist and private secretary of Eleftherios Venizelos, wrote in the Eleftheron Vima newspaper to denounce the fact that there existed no waste collection infrastructure in Athens, describing the city as a “vast rubbish town” and pointing out Gazochori as one of the neighbourhoods where the lack of hygiene goes beyond the limits of what is tolerable:

| “Go to Gazochori to see what is happening. It is the filthiest neighbourhood in this city. The streets are full of rubbish, and inside walled yards are heaps and hills of rubbish. Unbearable stench, flies, gnats, mosquitoes, all the insects in the world… that which puts the health of the residents in true and constant danger is the emptying of sanitationcarts within, or very close to, residential areas, as is the case in Gazohori,…” |

Kostas Biris described the neighbourhood as “…a shambles of huts and woeful shacks … a true Hell of misery and corruption” (Μπίρης 1966: 202).

According to local residents, the influx of internal migrants from Mani, Thessaly, Kefalonia, Kerkyra (Corfu) and the Aegean Islands continued until the mid-20th century, creating a culturally diversified residential area (Ζ.R.’s oral testimony, Industrial Gas Museum Oral Testimonies’ Archive). The choice of Gazochori as the place to settle in Athens had to do with the neighbourhood’s position at the fringe of the city’s urban centre. Its location outside the city plan meant that crude makeshift shacks could be built at a low cost while evading the scrutiny of zoning inspections and regulations.

“The Whores of Gazi” and Other Stories of Delinquency

In addition to the frequent epidemics, Gazochori became associated with one more thing: prostitution. A police ordinance of April 1894 “On common women and houses of debauchery” put Athens’ brothels “close to the gasworks premises”. The same ordinance described a three-level classification of common women, according to which, the third and lowest level comprised those who lived and worked in the brothels of Gazochori (Δρίκος 2002: 174-175). Classifying the neighbourhood’s prostitutes in this third level could be connected to an expletive that remained popular in later years: “Gazi whore” (Z.R.’s oral testimony, Industrial Gas Museum Oral Testimonies’ Archive). In 1897, police records show the arrest of two sex traffickers who tried to sell a 16-year-old maid “to the houses of ill-repute in Aeriofotos” ( Newspaper Empros/ Εμπρός 10 July 1897). Two months later, a schoolteacher from Methana was arrested in Gazochori while negotiating the “sale” of his wife to the brothels (Newspaper Empros/ Εμπρός 7 September 1897). These two incidents not only confirm the existence of brothels in the area but also seem to indicate that prostitution flourished there at the end of the 19th century. Gazochori would go on to become synonymous with prostitution, to the point that in 1900 the press was referring to the neighbourhood’s prostitutes as “the women of Gazochori” ( Newspaper Empros/Εμπρός 15 May 1900). ). It is worth noting that a reply sent by the Medical Council, to the Ministry of the Interior in 1905 on “secret brothels” does not mention Gazochori, but states that such businesses exist in the streets of Kerameikos (Thermopylon, Leonidou, Kerameikou, Kallergi, Deligiorgi) and Omonoia (Agiou Konstantinou, Satovriandou, Acharnon, Zinonos, Veranzerou, Solomou, Gamveta). Perhaps this is because Gazochori was considered to be at the fringes of the city. Many years later, Stefanos Stefanou discussed the area in an article, referring to it as “the territory of common women. ‘Let’s go to Gazi,’ said the soldiers and the bailiffs with their red coats and their whips in their hands” ( Newspaper Eleftheron Vima/ Ελεύθερον Βήμα, 9 July 1929).

Burglars and thieves often sought refuge in Gazochori and there were frequent brawls ( Newspaper Empros/ Εμπρός 31 December 1895, 23 October 1927, 30 June 1962).Armed brawls often involved soldiers, whose consistent presence in the area was a result to its proximity to the Engineer Corps barracks and, probably, to the area’s brothels ( Newspaper Skrip/ Σκριπ 23 November 1903).

As a working class neighbourhood, Gazochori was also the backdrop against which many love affairs played out, some of them fatal:

| “When you are young and in your prime and full of life and working in a smithy from dawn till dusk and the work and the fire are eating you up and you’re swimming in your own sweat and you’re dying at the anvil and losing your breath at the bellows, it is impossible not to fall in love with a pair of eyes that pass by that place where you’re hammering brass and iron. Something along these lines happened to the 20-year-old coppersmith Aristeidis Triantafyllopoulos, who fell in love four years ago with a pair of eyes belonging to then 15-year-old Katina Xenou…” (Newspaper Eleftheron Vima/ , 5 October 1924). |

| “Stamatis was a 28-year-old man. A woman called Thodora came across his path. She was 26… Both of them black marketeers, they became partners in trade. He was in love and she was wily, sensing his weakness and tormenting him.… he cut the thread of her life. The next morning, passers-by on Sofroniou Street stumbled upon the two bodies blocking the narrow alley.” ( Newspaper Eleftheron Vima/ Ελεύθερον Βήμα, 6 February 1943) |

However, beyond this delinquency, the working-class environment was favourable for the spread of communist ideas and therefore also for clashes with the police:

| “Regarding the clash with the communists in Gazohori, the following was ascertained”

Communists resident in the neighbourhood have been collecting small sums of money from residents to go towards supporting unemployed communists and to contribute to the coffers of the communist centre. They have also forced residents to buy Rizospastis [the newspaper of the Communist Party of Greece]. As a result, police carried out a surprise search that resulted in the arrest of many of the communists. The fighting between police and communists occurred during the search and approximately 50 shots were fired, injuring a policeman and the communist Dimakos. Later, another group of communists, believing that their ‘comrades’ had been arrested after being turned in by neighbourhood president Mr Haralambidis, attacked and beat him. Of the communists, five were arrested.” ( Newspaper Athinaika Nea/ Αθηναϊκά Νέα, 6 June 1933) |

Incidents of social deviance and criminal delinquency reconfirmed the neighbourhood’s symbolic position on the city’s fringes. For 56 years (1901-1957), Gazochori was also associated with Athens’ vegetable market, which was situated next to the gasworks on the corner of Iera Odos and Pireos Street (which is now a carpark that serves the metro station). The establishment of the vegetable market at the beginning of the 20th century seems to be connected not just with the trade of produce but also with the trade of hashish, as the so-called hasisopotes, as hashish smokers were colloquially referred to, frequented the tavernas and cookhouses that sprung up all around the market. The narrative that defined Gazochori as a hotbed of dangerous and immoral activities appears to have gradually waned after WW II. The intense emphasis on delinquent behaviours that was seen during the early 20th century is likely related to the wider spread of such phenomena and to the rhetoric of moral cleanliness and rehabilitation, which dominated the thinking of physicians, labour inspectors, sociologists and hygienists during that time (Platt 2000: 194-222).

Gazochori and the Urban Planning of Athens

Due to their proximity to Pireos Street, the commercial road that leads from Athens to Piraeus, the neighbourhoods that were established to the west and southwest of Athens—such as Pireos (today known as Kato Petralona), Gazochori, Hezolitharo (today known as Metaxourgeio), Akadimia Platonos, Iera Odos (Elaiotriveia neighbourhood) – attracted trade and manufacturing activities early on and were populated largely by lower income groups.

The area was incorporated into the city plan in 1880 and the city plan mostly followed the routes of existing older streets. Beginning in Gazohori, Orfeos Street crosses Elaionas following the ancient “Strata tis Koulouris” (archaic for “the road to Salamina”), a road once travelled by the Turkish traveller Evliya Celebi.

In 1908, A. Georgiadis’ Pinakas, which depicts the first official division of Athens into neighbourhoods, most streets in Gazohoridon’t even bear an official name. Nikolaos Igglesis’ 1928 Guide to Greece directory only lists 24 streets, compared to 38 that exist today. And until about 1940, the settlement appears to belong to the neighbourhood of Kerameikos, although a number of its streets appear to also belong to the neighbourhoods of Iera Odos (which stretched from 21 Iera Odos to the beginnings of Evmolpidon Street), Keiriadon (which stretched from 150-152 Pireos Street and reached the Engineer Corps barracks).

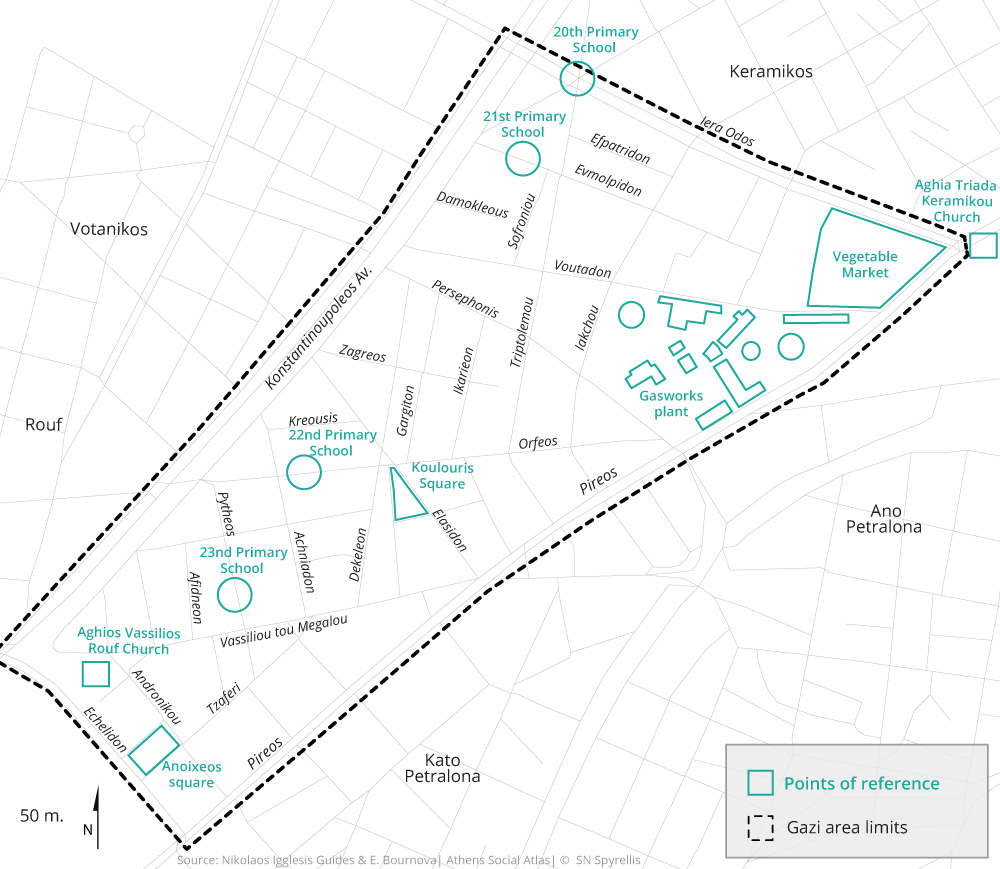

Despite not having clear borders, its main landmark and defining feature was the gasworks after all, Gazohori was probably delimited by Pireos, Konstantinoupoleos, Petrou Ralli and Iera Odos streets. However, the use of Petrou Ralli as one of the four streets that demarcated Gazohori was not clear until the 1950s. Maps from the early 20th century, such as the one from 1944, seem to show Vassileiou tou Megalou Street as the border, whilst a 1958 map seems to mark Echelidon Street as the area’s boundary.

Gazochori was not a formal parish. Two churches, Agios Vassileios at Rouf and Agia Triada at Kerameikos, were situated at the area’s two extremes, at the west and east end of Gazi, but neither was really located within it. Even Agios Vasileios, which was technically within the “borders” of Gazochori, was not a parish church, but was the chapel of the Ecclesiastical Orphanage of Vouliagmeni.

Gazochori was a neighbourhood without public squares. Locals recognise only one “common”: Koulouris Square, the small area at the intersection of Stratonikis, Elasidon and Orfeos streets. Anoixeos Square, which is located at the neighbourhood’s edge, is much more recent.

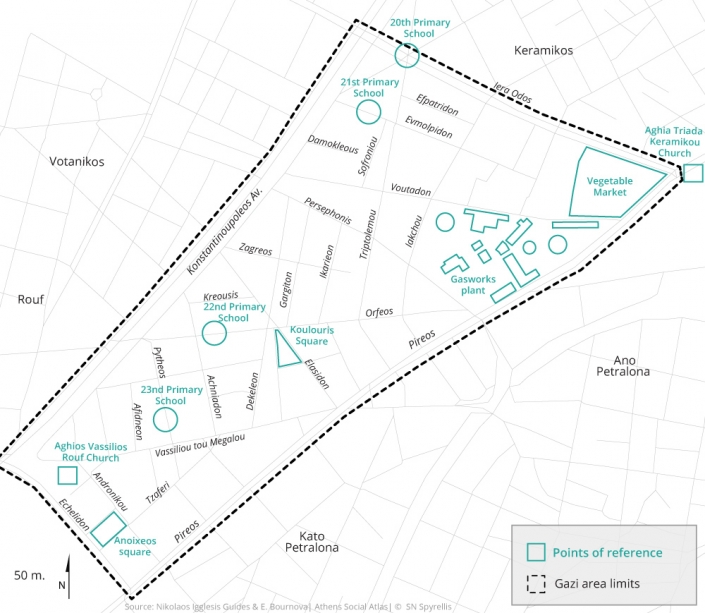

Map 3: Points of reference in the Gazochori neighbourhood

The Residents and Businesses of Gazochori, According to Nikolaos Igglesis’ Guides, 1910-1958

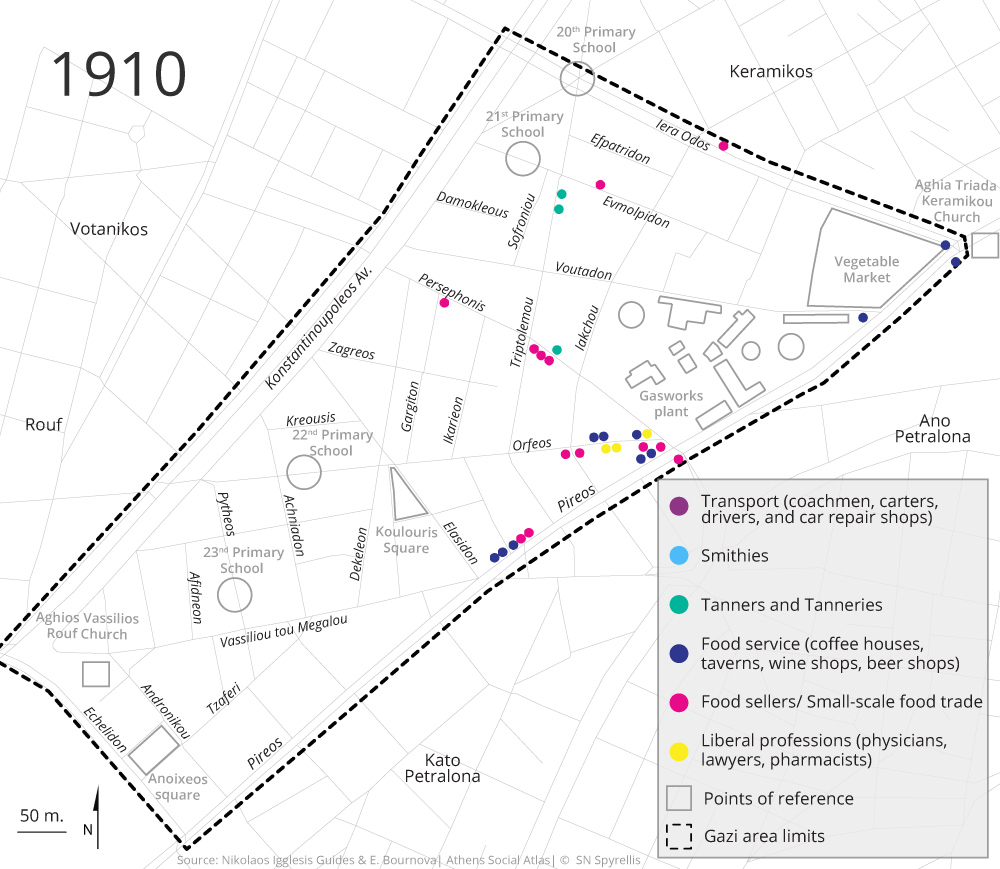

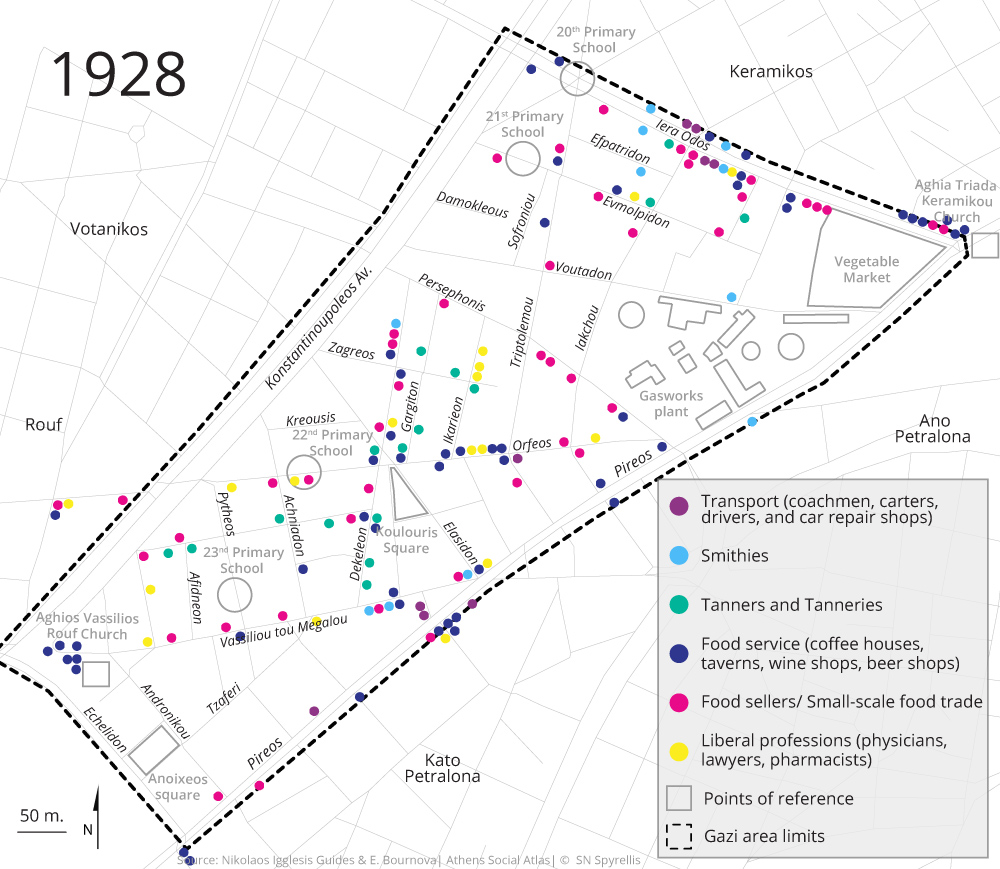

Thanks to Nikolaos Igglesis’ Guide to Greece directories, we are able to study the socioprofessional make-up of Gazohori’s population and the economic activities that took place in the area. The directories for 1910 and 1928 (the latter being the most comprehensive as it was very likely based on the records of the population census of 1928) list both business premises and individuals, whereas those for 1939 and 1958 list only business premises—with the exception of liberal professions such as physicians and lawyers, whose names and addresses were likely provided by their respective professional associations. As such, the very form and data of these directories dictate the limits of the study of the evolution of the socioprofessional make-up and economic activities of Gazochori; we can track changes in the occupations of the area’s male residents for 1910 and 1928, and we can track the evolution of local businesses between 1939 and 1958.

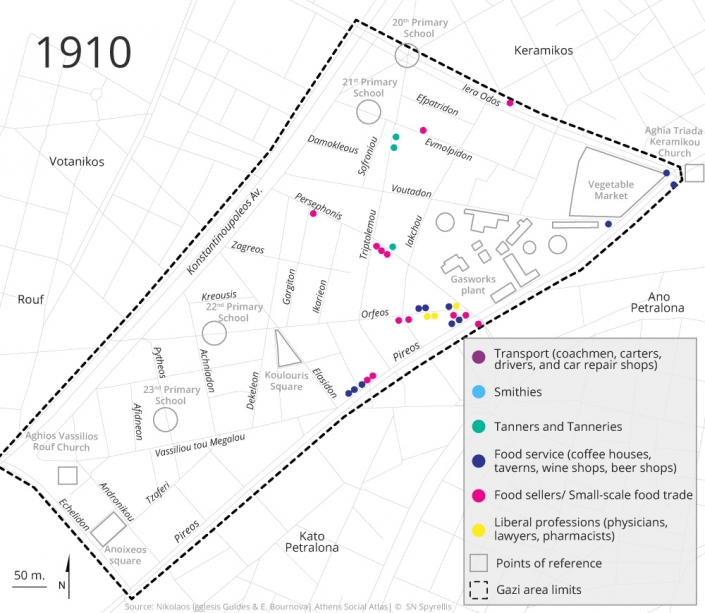

According to the 1910 Guide to Greece (Table 1), just 127 men with a trade or steady employment resided in the neighbourhood. Neither the female population nor the gasworks workers are listed, with two exceptions: a gasworks inspector and a gasworks tinsmith. Two blacksmiths and a mechanic are also listed, but it is not specified whether they were employed at the gasworks. In 1910, coffeehouses, cookhouses, wine shops and small food stalls were the main economic activities, concentrated in an arch-like area around the factory. The social elite is represented by three lawyers and the gasworks inspector (Map 4).

Table 1: Socioprofessional categories of the male population of Gazochori, according to Nikolaos Igglesis’ Guide to Greece directory (1910)

Map 4: Location of businesses in the Gazochori neighbourhood in 1910

We don’t know the exact numbers of the neighbourhood’s population because Greek census findings at the district or neighbourhood level are not published. All we know is that in 1920, Gazi, Kerameikos and Metaxourgeio—collectively known as “Kerameikos exo” (literally “outside”, or west, of the ancient cemetery of Kerameikos)—had approximately 20.000 residents comprising a total of 4.321 families.

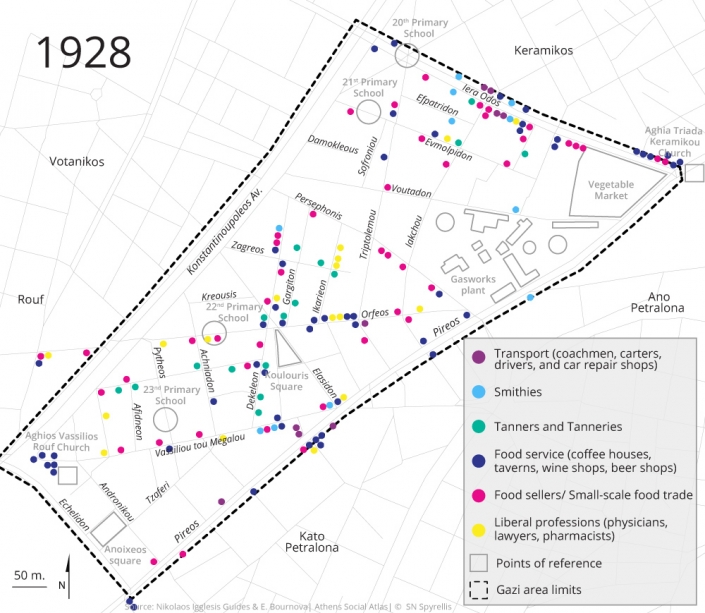

The neighbourhood’s population appears to have been constantly growing, either due to the arrival of internal migrants or due to the influx of refugees from Asia Minor. Igglesis’ Guide of 1928 (Table 2) lists almost 1.000 individuals and business premises in Gazochori, as well as another 114 individuals whose address is noted as “the vegetable market” and who we assume did not actually live in Gazochori (Map 5).

Table 2: Socioprofessional categories of the male population of Gazochori, according to Nikolaos Igglesis’ Guide to Greece directory (1928)

Map 5: Location of businesses in the Gazochori neighbourhood in 1928

The largest category, “artisans/craftsmen, retailers, hoteliers, food service professions”—representing approximately half of the economically active residents recorded by the editor of the 1928 directory—comprise primarily food services professions, including coffeehouse keepers, wine-sellers, tavern keepers and grocers (Map 6) who conducted their business from very small premises and whose financial situation did not much differ from that of their clients. Their sheer numbers point to tiny businesses and confirms the neighbourhood’s working class character. That same year, the press referred to an “excess of shopkeepers” in Athens (article titled “The crisis of our large urban centres-Athens: The city of phenomenal prosperity” Newspaper Eleftheron Vima/ Ελεύθερον Βήμα 5 February 1928), a result of the considerable increase in the number of grocers, who according to the article’s author went from 3.116 in 1920 to 4.755 in 1928: “Many have fallen to the level of the proletariat.”

Map 6: Evolution of the location of food services, including coffeehouse keepers, wine-sellers, tavern keepers and grocers, in the Gazochori neighboorhood (1910-1939)

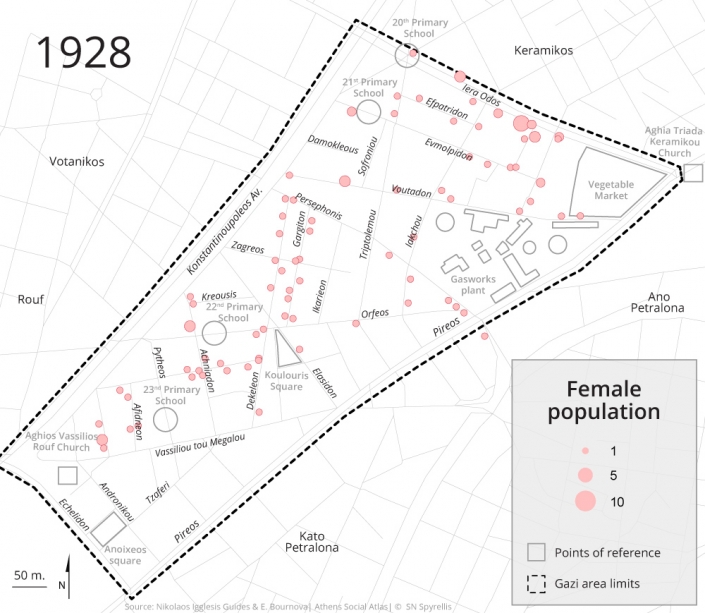

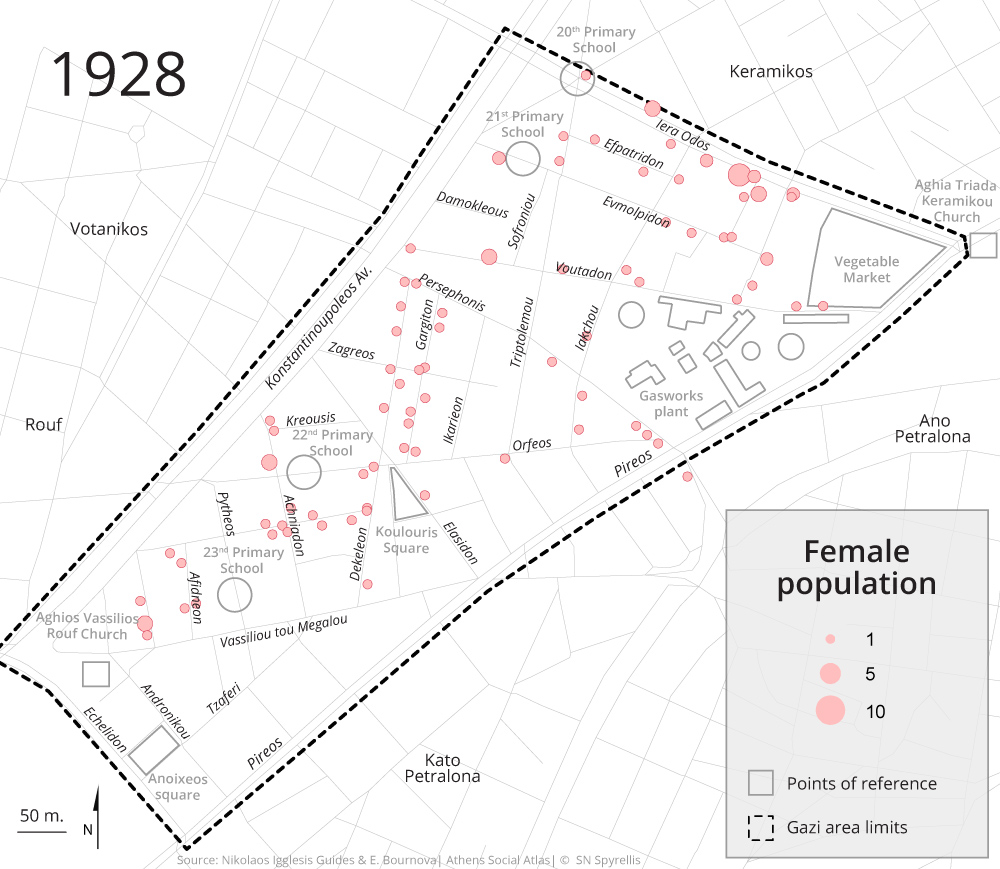

In 1928, part of the neighbourhood’s female population is also included in the directory: 99 women in total. Of these, just three are listed with an occupation and all three of them are midwives. The rest of the women are noted as widows or housewives, as is also the case with civil status documents of that era (Map 7).

Map 7: Female population in 1928

Obviously not all gasworks employees and workers resided in Gazohori. Nor was the entirety of the neighbourhood’s economically active male population recorded in Igglesis’ Guide, as there were likely many more day labourers than the approximately 100 listed therein.

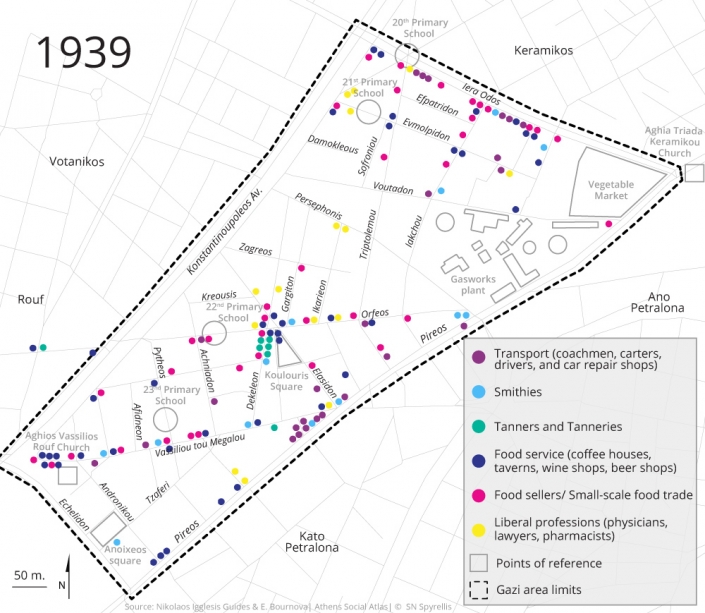

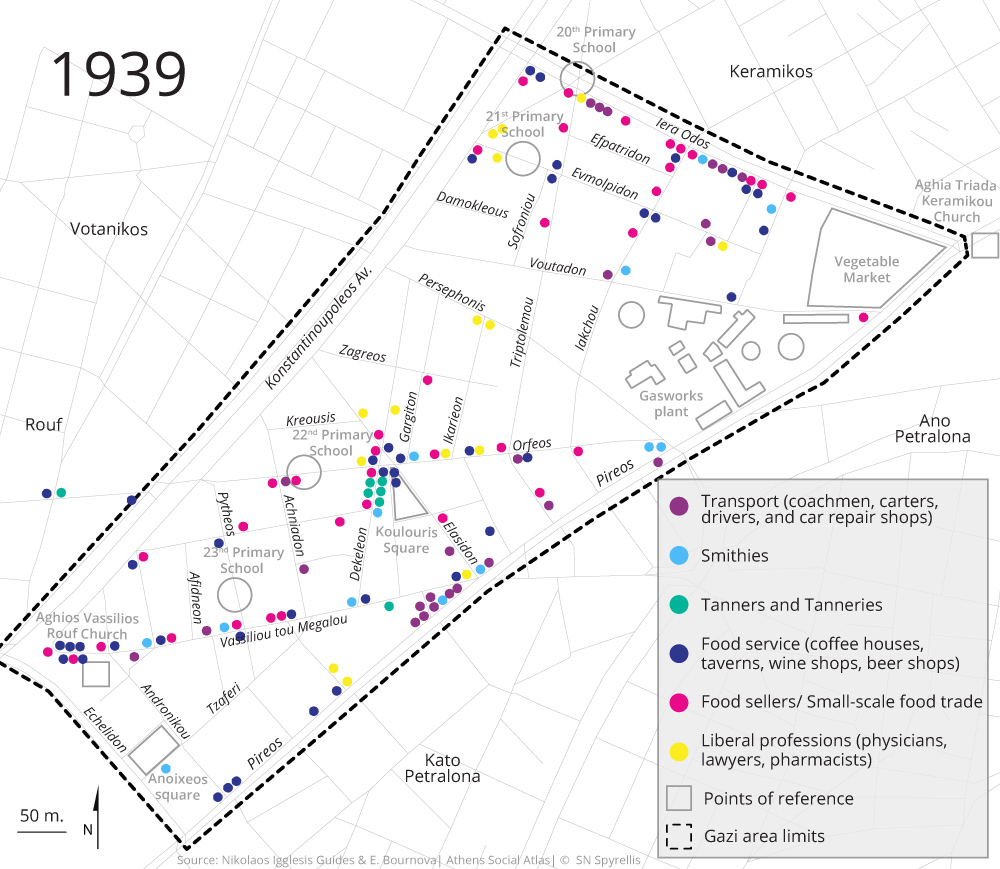

On the eve of World War II, there were, according to Igglesis’ 1939 Guide (Map 8), four primary schools in the neighbourhood: the 20th Primary School, at the intersection of Megalou Alexandrou Street and Iera Odos; the 21st Primary School, at 39 Evmolpidon Street; the 22nd Primary School, on Orfeos Street; and the 23rd Primary School, on Dialeon Street. The Vocational School that is mentioned is probably the Engineer Corps training facility at Rouf. In 1939, there were still three hay shops operating on Pireos Street, of the six there had been there in 1910.

Car workshops and machine shops appeared, located primarily on main thoroughfares, in 1939 (Map 9). The neighbourhood’s growing population benefited the food trade (such as grocers, greengrocers, butchers, and small food stalls) as well as cookhouses, wine shops and coffeehouses, which spread into numerous side streets but primarily along major roads.

Map 8: Location of businesses in the Gazochori neighbourhood in 1939

Map 9: Evolution of the location of food sellers and small-scale food trade in the Gazochori neighboorhood (1910-1958)

Meanwhile, there were numerous shoemakers’ workshops and furniture workshops/cooperages/cart makers’ workshops as well as a textile workshop, two seed-oil mills, a rope workshop, a biscuit factory, two pharmacies. In this Gazohori of artisans and craftsmen, there were but few representatives of the liberal professions on the eve of the Second World War: three lawyers and about ten physicians.

Gazohori During the Nazi Occupation

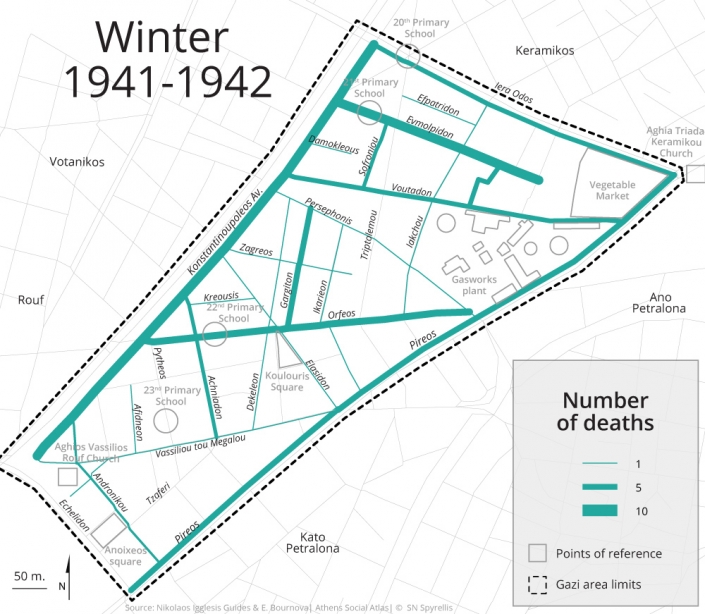

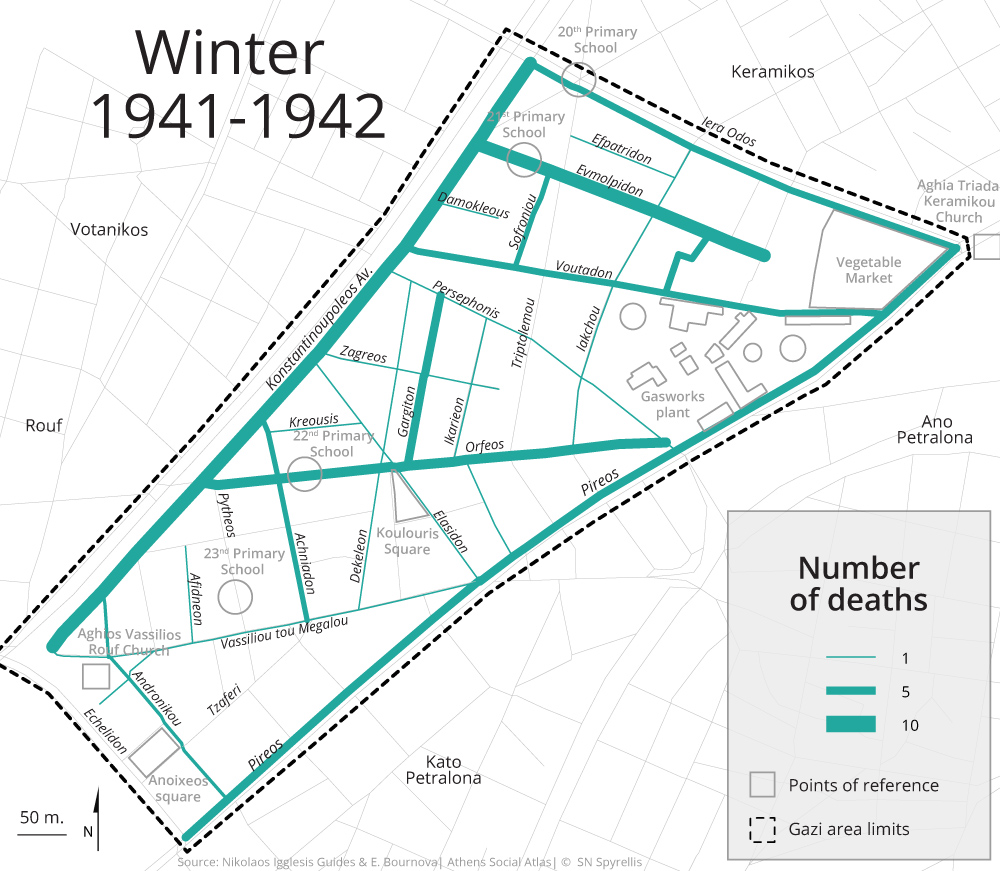

According to the records of the Athens Registry Office, of the 65 individuals who died of starvation in Gazochori during the winter of 1941-42 (Map 10), 18 originally came from the islands, 10 from Istanbul, Asia Minor and Pontus, eight from central and northern Greece, and just a handful from Peloponnesos (seven) and the Mainland and Evia region (four).The remaining 16 had been born in Athens. The islanders, the refugees and those originally from northern Greece were the farthest from their home regions; effectively cut-off, they were unable to obtain food from there and were the first victims claimed by the famine that struck Greek cities and the capital worst of all (Μπουρνόβα, 2005) Most of them were labourers or artisans. We can assume that Gazochori attracted refugees and internal migrants largely from the Aegean and Ionian islands and to a lesser extent from the other provinces (Μπουρνόβα & Δημητροπούλου, 2015).

Map 10: Number of deaths in Gazochori. Winter 1941-1942

Tracing a Picture of Post-War Gazochori

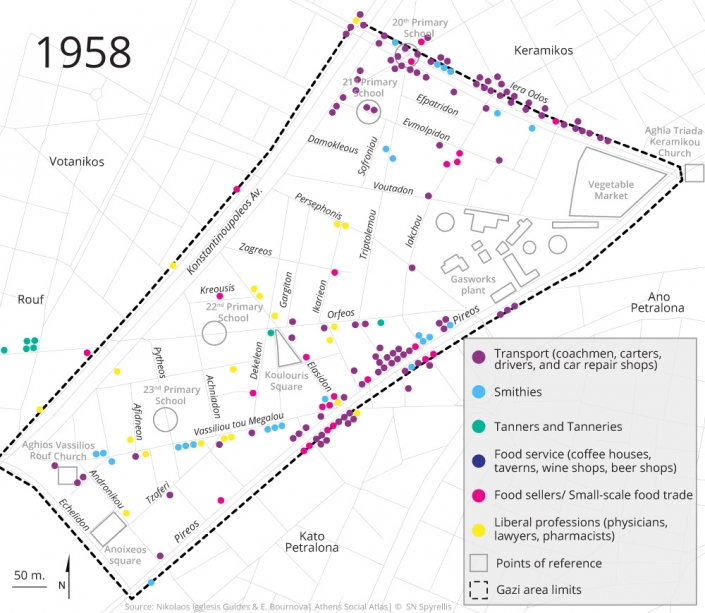

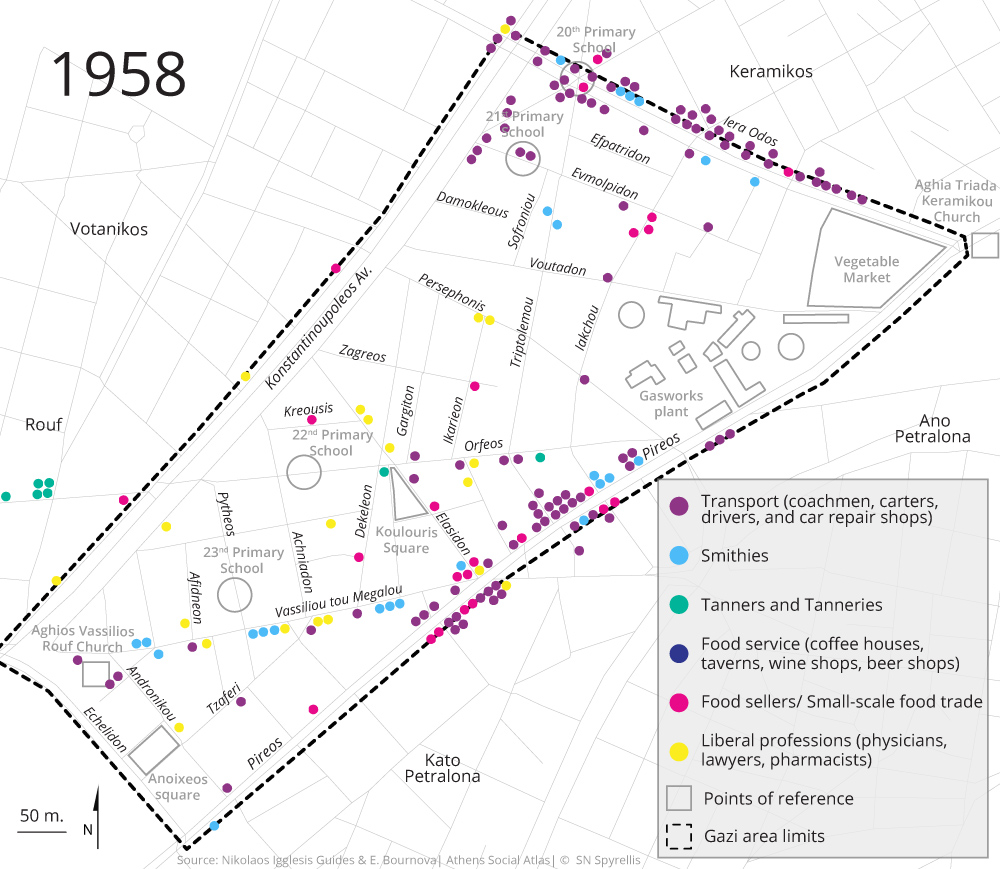

With few exceptions, Igglesis’ 1958 Guide to Greece (Map 11) no longer listed coffee houses, cookhouses and wine shops, nor food stalls and food shops. It also excluded the shops of the vegetable market, which were the neighbourhood’s key characteristic until 1960. This served to highlight the neighbourhood’s industrial character: cars and car workshops (Map 12) along with machine shops and forges (Map 13) become the predominant economic activities, taking place near the neighbourhood’s borders, along the three main roads: Pireos, Iera Odos, and Echelidon.

Map 11: Location of businesses in the Gazochori neighbourhood in 1958

Map 12 : Evolution of the location of coachmen, carters, drivers and car repair shops in the Gazochori neighboorhood (1928-1958)

Map 13: Evolution of the location of Smithies in the Gazochori neighboorhood

Beyond the automotive trades, there are also seven textile workshops, six oil mills, six tanneries (which were responsible for the foul odours and which were concentrated mostly on Orfeos Street) (Map14), and a number of soap works, marble workshops, carpenters’ workshops, etc. As was the case before the war, the elite remains limited: a few lawyers and 13 physicians.

Overall, liberal professions in Gazi in the period from the beginning of the 20th century until 1960 belong to the health sector and gradually spread throughout the area (Map 15).

Map 14 : Evolution of the location of Tanners and Tanneries in the Gazochori neighboorhood (1910-1958)

Map 15: Evolution of the location of Liberal professions in the Gazochori neighboorhood (1910-1958)

Regardless of the economic activities that are listed in Igglesis’ directory, it is clear that Gazochori was inhabited by labourers, artisans, shopkeepers and craftsmen: By the end of the 1950s, only the physicians and dentists that cover local needs continue to reside in the neighbourhood, constituting the area’s highest socio-professional category.

From the 1960s on, members of the Muslim community of Thrace begin to settle in the area, at the same time as existing residents begin to leave their houses and move to other neighbourhoods. This new wave of internal migrants to Gazi continued over the following years and peaked during the 1980s (Αβραμοπούλου & Καρακατσάνης 2002).

The Story of a Street: The Triptolemou Street

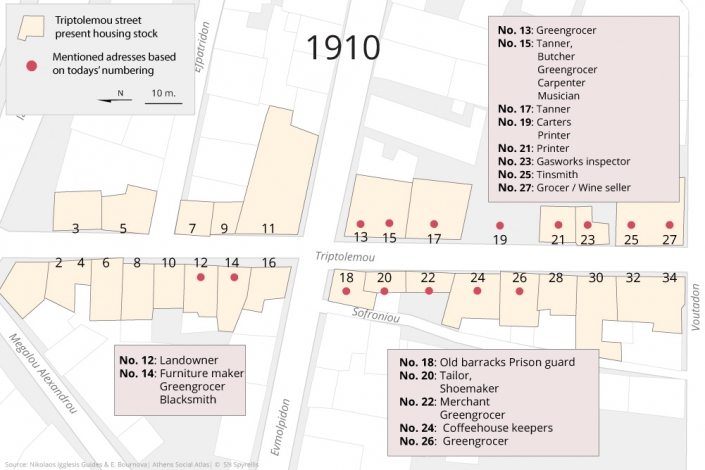

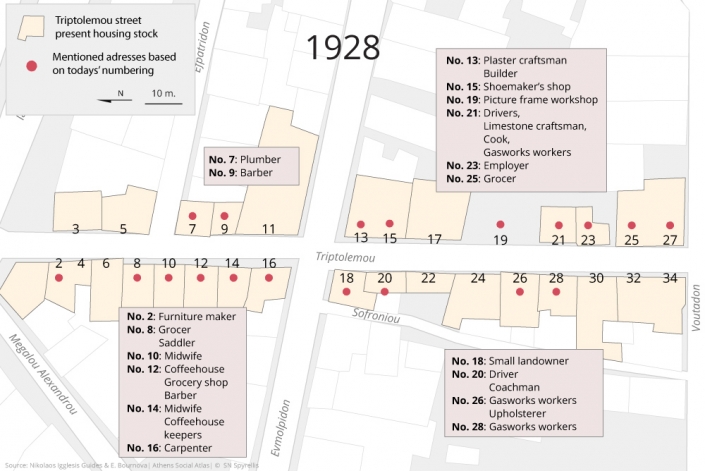

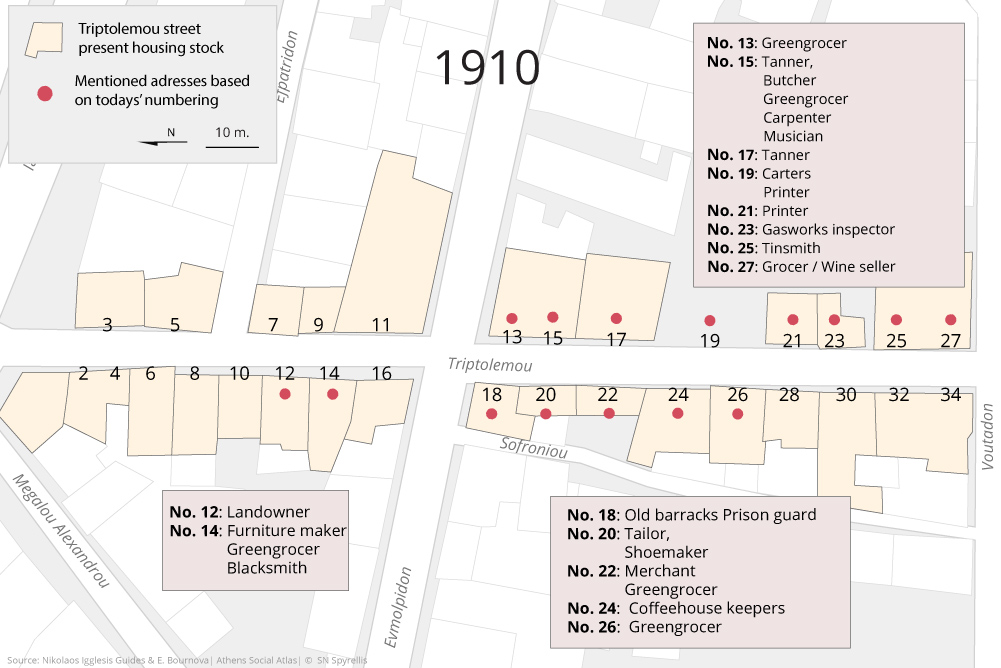

At the dawn of the 20th century, Triptolemou Street brought together a multitude of occupations and activities. Firstly, there was a considerable variety of artisans: two tanners, a furniture maker, a carpenter, a tailor, a blacksmith, two printers, and two shoemakers; in total, 10 artisans resided on this street. Secondly, there was also a significant number of food sellers: five greengrocers, a butcher, and a grocer/wine-seller. In addition to these there were a coffeehouse keep, a musician, and a carter, as well as a gasworks tinsmith and a gasworks inspector and the foreman of the Old Barracks prison (Palaion Stratonon) (Map 16 [2] ).

Map 16: Triptolemou street in 1910

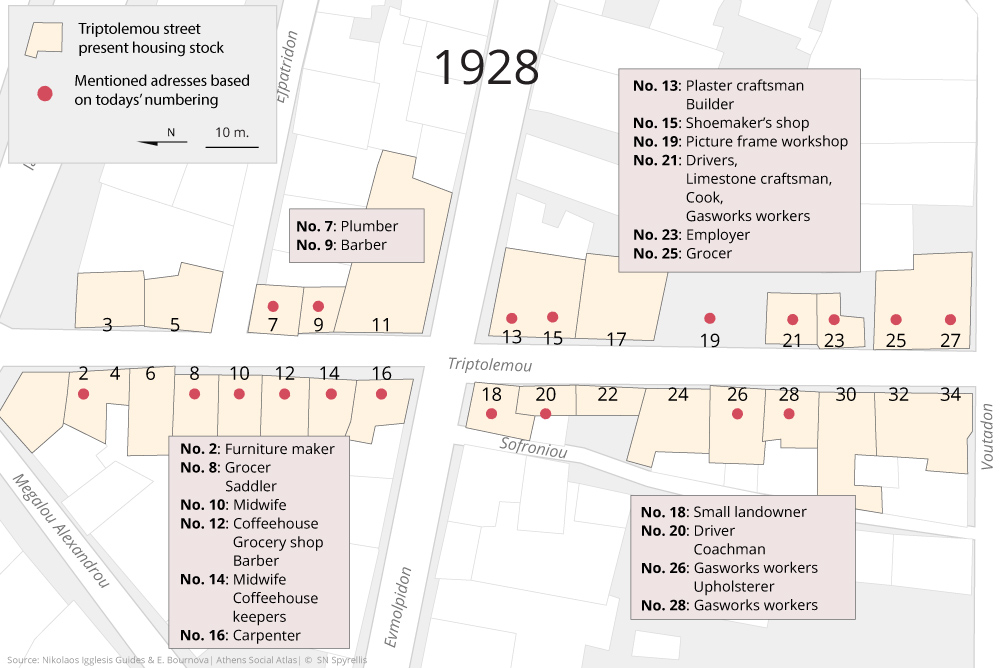

In the late 1920s (Map 17), the street’s population had increased considerably, yet there seemed to be little continuity with previous residents: None of the aforementioned men seem to have stayed in the neighbourhood, confirming the geographic mobility of the working classes that has also been observed in other Western capitals. Of the artisans, four worked with wood, two were shoemakers, one was a plumber, one an upholsterer, and two worked in construction. The population growth also led to an increase in small grocers/wine-shops, of which there were now four; there were also two greengrocers, three coffeehouse keepers, and two barbers, while three drivers also appear on the list. Finally, there were also gasworks workers as well as a midwife, a cook, a haberdasher, a gardener…This was a street full of life and diversity.

In addition to the midwife, only one more woman was mentioned: Anast. Palouba, a widow whose occupation is noted as “housewife” and who lived at No. 14, the same address as Mr A. Roussis’ coffeehouse, but also where coffeehouse keeper Mr I. Koumas resided. These were likely rudimentary dwellings, single rooms around a shared courtyard rather than the two-storey buildings found in the centre of Athens, which usually housed a shop on the ground floor and living quarters above it.

Map 17: Triptolemou street in 1928

Occupational records for Triptolemou Street on the eve of the Second World War are rather sparse and limited to about 10 businesses. However, it is interesting to note that in 1939 A. Roussis maintained his coffeehouse at the same address, just like grocer/wine-seller G. Platanitis and shoemaker D.Papaioannou, who had not relocated from their premises.

Almost 20 years later, in 1958, even though the record remains sparse, there is a sense of change in the variety of activities: M. Varvayiannis and R. Nahamas’ weaving workshop, an electrical appliances shop and K. Zografou’s vocational school marked a new era not just for the street but for the entire neighbourhood. Yet older elements remained: the Egglezakis Bros furniture workshop, located in the same building complex as a smithy and as A. Tsantilis’ picture frame workshop, which had been there since before the war. Practically across the street, there was another smithy, belonging to S. Gordatos, which had been established in that location since 1939. But the street had changed. The tanneries had moved away and had been replaced by other, less polluting workshops and, of course, the vocational school.

In addition to the aforementioned, two other groups of men were well represented in Gazochori until the vegetable market was relocated in 1960: greengrocers and soldiers. Greengrocers would arrive before dawn to sell their fresh fruit and vegetables to the rest of the city’s greengrocers, while soldiers came to visit Gazi’s “girls”. Nonetheless, the existence of four schools, and the mentions of “housewives” and widowed women in the records, indicate that despite the neighbourhood’s bad reputation, many families made it their home, contributing to the diversity of Gazochori’s population.

Social Protest and Environmentalism

During the 1970s, residents formed cultural/neighbourhood associations, which aimed to remove the gasworks from the area. The plant, however, was not shut down during the 1970s and continued to operate until 1984 [3]. During that time, local associations continued building momentum and Greek society was introduced to a new term: the Athenian “nefos” (literally “cloud”), as the smog over Athens came to be known (Ριζοσπάστης 16 September 1982, Ελευθεροτυπία 22 February 1984). Relocating the gasworks appeared to be a political and social dead end. In 1982, a group of protesters tore down part of the wall surrounding the gasworks in protest (Έθνος 29 June 1982). In 1986, the Ministry of Culture declared the gasworks a heritage site (Φ.Ε.Κ. 621/Β/26 September 1986) and from 1999 on the Technopolis Industrial Park (today Technopolis City of Athens) signalled a change of use in the area. The neighbourhood’s gentrification during the 2000s led to the disgruntlement of many local residents who, despite seeing the value of their properties increase, experienced the proliferation of amusement and entertainment venues in the area as violent and wild. Gazochori remained one of Athens’ liveliest neighbourhoods for decades, a place on the fringes of the city and of society, at the edge of delinquency and lawfulness.

[1] Aeriofotos and fotaerio are Greek terms for “lighting gas factory” and “lighting gas”. Aeriofotos was dominant until 1952 and was subsequently replaced by fotaerio. This shift was also recorded in the company’s name, which was changed to Dimotiki Epiheirisi Fotaeriou Athinon (Athens Municipal Gasworks Company) in 1952 (Στογιαννίδης&Χατζηγώγας 2013: 15, 58).

[2] The geo-localization of the addresses along the Triptolemou street follows todays’ numbering. Comparisons with a 1958 map have shown that the changes in the numbers and the housing stock are limited

[3] For more on plans to relocate the gasworks to other areas in Attica, see Στογιαννίδης & Χατζηγώγας 2013: 62-64.

Entry citation

Bournova, E., Stoyannidis, Y. (2018) Gazochori: The History of a Neighbourhood (1857–1980), in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/gazochori/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.85

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Αβραμοπούλου Ε και Καρακατσάνης Λ (2002) Διαδρομές της ταυτότητας από τη Δυτική Θράκη στο Γκάζι: Αναστοχασμοί και συγκρούσεις στη διαμόρφωση συλλογικών ταυτοτήτων. Η περίπτωση των τουρκόφωνων μουσουλμάνων στο Γκάζι. Θέσεις 79.

- Δρίκος Θ (2002) Η πορνεία στην Ερμούπολη το 19ο αι. (1820-1900). Αθήνα: Ελληνικά Γράμματα.

- Ιγγλέσης Ν (1958) Εμπορικός Οδηγός της Ελλάδος. Αθήνα: 1910-1928-1939-1958.

- Μπίρης Κ (1966) Aι Αθήναι από του 19ου εις τον 20ον αιώνα. Αθήνα: Έκδοσις του Καθιδρύματος Πολεοδομίας και Ιστορίας των Αθηνών.

- Μπουρνόβα Ε (2005) Θάνατοι από πείνα: η Αθήνα το χειμώνα του 1941-1942. Αρχειοτάξιο 7: 52–73.

- Μπουρνόβα Ε και Δημητροπούλου Μ (2015) Κοινωνική-επαγγελματική διαστρωμάτωση της πρωτεύουσας, 1860-1940. Στο: Μαλούτας Θ και Σπυρέλλης ΣΝ (επιμ.), Κοινωνικός άτλαντας της Αθήνας, Αθήνα. Available from: http://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/άρθρο/338/.

- Στογιαννίδης Γ (2015) Βιομηχανικά μνημεία και δημόσια μνήμη. Το Βιομηχανικό Μουσείο Φωταερίου αφηγείται. Στο: Νάκου Ε και Γκαζή Α (επιμ.), Η προφορική ιστορία στα μουσεία και στην εκπαίδευση, Αθήνα: Νήσος.

- Στογιαννίδης Γ (2016) Το κοινωνικό ζήτημα της φυματίωσης και τα σανατόρια της Αθήνας, 1890-1940. Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλίας.

- Στογιαννίδης Γ και Χατζηγώγας Σ (2013) Το εργοστάσιο φωταερίου της Αθήνας. Η ιστορία, η τεχνολογία, οι άνθρωποι, το μουσείο. Αθήνα: Τεχνόπολις Δήμου Αθηναίων.

- Bournova E and Garden M (2014) Naître à Athènes dans la première moitié du xxe siècle. Démographie et institutions. In: Annales de démographie historique, Belin, pp. 209–230.

- Platt HL (2000) Jane Addams and the ward boss revisited: Class, politics, and public health in Chicago, 1890-1930. Environmental History, JSTOR 5(2): 194–222.

![Map 6: Evolution of the location of food services, including coffeehouse keepers, wine-sellers, tavern keepers and grocers, in the Gazochori neighboorhood (1910-1939) In 1928, part of the neighbourhood’s female population is also included in the directory: 99 women in total. Of these, just three are listed with an occupation and all three of them are midwives. The rest of the women are noted as widows or housewives, as is also the case with civil status documents of that era (Map 7). Map 7: Female population in 1928 Obviously not all gasworks employees and workers resided in Gazohori. Nor was the entirety of the neighbourhood’s economically active male population recorded in Igglesis’ Guide, as there were likely many more day labourers than the approximately 100 listed therein. On the eve of World War II, there were, according to Igglesis’ 1939 Guide (Map 8), four primary schools in the neighbourhood: the 20th Primary School, at the intersection of Megalou Alexandrou Street and Iera Odos; the 21st Primary School, at 39 Evmolpidon Street; the 22nd Primary School, on Orfeos Street; and the 23rd Primary School, on Dialeon Street. The Vocational School that is mentioned is probably the Engineer Corps training facility at Rouf. In 1939, there were still three hay shops operating on Pireos Street, of the six there had been there in 1910. Car workshops and machine shops appeared, located primarily on main thoroughfares, in 1939 (Map 9) . The neighbourhood’s growing population benefited the food trade (such as grocers, greengrocers, butchers, and small food stalls) as well as cookhouses, wine shops and coffeehouses, which spread into numerous side streets but primarily along major roads. Map 8: Location of businesses in the Gazochori neighbourhood in 1939 Map 9: Evolution of the location of food sellers and small-scale food trade in the Gazochori neighboorhood (1910-1958) Meanwhile, there were numerous shoemakers’ workshops and furniture workshops/cooperages/cart makers’ workshops as well as a textile workshop, two seed-oil mills, a rope workshop, a biscuit factory, two pharmacies. In this Gazohori of artisans and craftsmen, there were but few representatives of the liberal professions on the eve of the Second World War: three lawyers and about ten physicians. Gazohori During the Nazi Occupation According to the records of the Athens Registry Office, of the 65 individuals who died of starvation in Gazochori during the winter of 1941-42 (Map 10), 18 originally came from the islands, 10 from Istanbul, Asia Minor and Pontus, eight from central and northern Greece, and just a handful from Peloponnesos (seven) and the Mainland and Evia region (four).The remaining 16 had been born in Athens. The islanders, the refugees and those originally from northern Greece were the farthest from their home regions; effectively cut-off, they were unable to obtain food from there and were the first victims claimed by the famine that struck Greek cities and the capital worst of all (Μπουρνόβα, 2005) Most of them were labourers or artisans. We can assume that Gazochori attracted refugees and internal migrants largely from the Aegean and Ionian islands and to a lesser extent from the other provinces (Μπουρνόβα & Δημητροπούλου, 2015). Map 9: Number of deaths in Gazochori. Winter 1941-1942 Tracing a Picture of Post-War Gazochori With few exceptions, Igglesis’ 1958 Guide to Greece (Map 11) no longer listed coffee houses, cookhouses and wine shops, nor food stalls and food shops. It also excluded the shops of the vegetable market, which were the neighbourhood’s key characteristic until 1960. This served to highlight the neighbourhood’s industrial character: cars and car workshops (Map 12) along with machine shops and forges (Map 13) become the predominant economic activities, taking place near the neighbourhood’s borders, along the three main roads: Pireos, Iera Odos, and Echelidon. Map 11: Location of businesses in the Gazochori neighbourhood in 1958 Map 12 : Evolution of the location of coachmen, carters, drivers and car repair shops in the Gazochori neighboorhood (1928-1958) Map 13: Evolution of the location of Smithies in the Gazochori neighboorhood Beyond the automotive trades, there are also seven textile workshops, six oil mills, six tanneries (which were responsible for the foul odours and which were concentrated mostly on Orfeos Street) (Map14), and a number of soap works, marble workshops, carpenters’ workshops, etc. As was the case before the war, the elite remains limited: a few lawyers and 13 physicians. Overall, liberal professions in Gazi in the period from the beginning of the 20th century until 1960 belong to the health sector and gradually spread throughout the area (Map 15). Map 14 : Evolution of the location of Tanners and Tanneries in the Gazochori neighboorhood (1910-1958) Map 15: Evolution of the location of Liberal professions in the Gazochori neighboorhood (1910-1958) Regardless of the economic activities that are listed in Igglesis’ directory, it is clear that Gazochori was inhabited by labourers, artisans, shopkeepers and craftsmen: By the end of the 1950s, only the physicians and dentists that cover local needs continue to reside in the neighbourhood, constituting the area’s highest socio-professional category. From the 1960s on, members of the Muslim community of Thrace begin to settle in the area, at the same time as existing residents begin to leave their houses and move to other neighbourhoods. This new wave of internal migrants to Gazi continued over the following years and peaked during the 1980s (Αβραμοπούλου & Καρακατσάνης 2002). The Story of a Street: The Triptolemou Street At the dawn of the 20th century, Triptolemou Street brought together a multitude of occupations and activities. Firstly, there was a considerable variety of artisans: two tanners, a furniture maker, a carpenter, a tailor, a blacksmith, two printers, and two shoemakers; in total, 10 artisans resided on this street. Secondly, there was also a significant number of food sellers: five greengrocers, a butcher, and a grocer/wine-seller. In addition to these there were a coffeehouse keep, a musician, and a carter, as well as a gasworks tinsmith and a gasworks inspector and the foreman of the Old Barracks prison (Palaion Stratonon) (Map 16 [2] ). Map 16: Triptolemou street in 1910 In the late 1920s (Map 17), the street’s population had increased considerably, yet there seemed to be little continuity with previous residents: None of the aforementioned men seem to have stayed in the neighbourhood, confirming the geographic mobility of the working classes that has also been observed in other Western capitals. Of the artisans, four worked with wood, two were shoemakers, one was a plumber, one an upholsterer, and two worked in construction. The population growth also led to an increase in small grocers/wine-shops, of which there were now four; there were also two greengrocers, three coffeehouse keepers, and two barbers, while three drivers also appear on the list. Finally, there were also gasworks workers as well as a midwife, a cook, a haberdasher, a gardener…This was a street full of life and diversity. In addition to the midwife, only one more woman was mentioned: Anast. Palouba, a widow whose occupation is noted as “housewife” and who lived at No. 14, the same address as Mr A. Roussis’ coffeehouse, but also where coffeehouse keeper Mr I. Koumas resided. These were likely rudimentary dwellings, single rooms around a shared courtyard rather than the two-storey buildings found in the centre of Athens, which usually housed a shop on the ground floor and living quarters above it. Map 17: Triptolemou street in 1928 Occupational records for Triptolemou Street on the eve of the Second World War are rather sparse and limited to about 10 businesses. However, it is interesting to note that in 1939 A. Roussis maintained his coffeehouse at the same address, just like grocer/wine-seller G. Platanitis and shoemaker D.Papaioannou, who had not relocated from their premises. Almost 20 years later, in 1958, even though the record remains sparse, there is a sense of change in the variety of activities: M. Varvayiannis and R. Nahamas’ weaving workshop, an electrical appliances shop and K. Zografou’s vocational school marked a new era not just for the street but for the entire neighbourhood. Yet older elements remained: the Egglezakis Bros furniture workshop, located in the same building complex as a smithy and as A. Tsantilis’ picture frame workshop, which had been there since before the war. Practically across the street, there was another smithy, belonging to S. Gordatos, which had been established in that location since 1939. But the street had changed. The tanneries had moved away and had been replaced by other, less polluting workshops and, of course, the vocational school. In addition to the aforementioned, two other groups of men were well represented in Gazochori until the vegetable market was relocated in 1960: greengrocers and soldiers. Greengrocers would arrive before dawn to sell their fresh fruit and vegetables to the rest of the city’s greengrocers, while soldiers came to visit Gazi’s “girls”. Nonetheless, the existence of four schools, and the mentions of “housewives” and widowed women in the records, indicate that despite the neighbourhood’s bad reputation, many families made it their home, contributing to the diversity of Gazochori’s population. Social Protest and Environmentalism During the 1970s, residents formed cultural/neighbourhood associations, which aimed to remove the gasworks from the area. The plant, however, was not shut down during the 1970s and continued to operate until 1984 [3]. During that time, local associations continued building momentum and Greek society was introduced to a new term: the Athenian “nefos” (literally “cloud”), as the smog over Athens came to be known (Ριζοσπάστης 16 September 1982, Ελευθεροτυπία 22 February 1984). Relocating the gasworks appeared to be a political and social dead end. In 1982, a group of protesters tore down part of the wall surrounding the gasworks in protest (Έθνος 29 June 1982). In 1986, the Ministry of Culture declared the gasworks a heritage site (Φ.Ε.Κ. 621/Β/26 September 1986) and from 1999 on the Technopolis Industrial Park (today Technopolis City of Athens) signalled a change of use in the area. The neighbourhood’s gentrification during the 2000s led to the disgruntlement of many local residents who, despite seeing the value of their properties increase, experienced the proliferation of amusement and entertainment venues in the area as violent and wild. Gazochori remained one of Athens’ liveliest neighbourhoods for decades, a place on the fringes of the city and of society, at the edge of delinquency and lawfulness. [1] Aeriofotos and fotaerio are Greek terms for “lighting gas factory” and “lighting gas”. Aeriofotos was dominant until 1952 and was subsequently replaced by fotaerio. This shift was also recorded in the company’s name, which was changed to Dimotiki Epiheirisi Fotaeriou Athinon (Athens Municipal Gasworks Company) in 1952 (Στογιαννίδης&Χατζηγώγας 2013: 15, 58). [2] The geo-location of addresses along the Triptolemou street follows todays’ numbering. Comparisons with a 1958 map have shown that the changes in the numbers and the housing stock are limited [3] For more on plans to relocate the gasworks to other areas in Attica, see Στογιαννίδης & Χατζηγώγας 2013: 62-64.](https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/tx130_V4_en-1-705x613.gif)