Gentrification in the neighbourhoods of the Athenian centre

Alexandri Georgia

Built Environment, Politics, Quartiers

2015 | Dec

Gentrification refers to the spatial and social processes in the restructuring of deprived city areas. As the process evolves, older and weaker – in financial and political terms – populations are displaced and replaced by middle and upper social strata. At the same time, land prices increase and capital gains are generated mainly through the formation of a rent gap (Smith, 1986). The rent gap refers to the difference between actual and potential rents and reflects the gains formed in the land market in a region that shows “gentrification” trends. As this process develops, the urban landscape changes as new residents impose their aesthetic preferencesLand use also changes, with the prevalence of upgraded and more profitable uses that serve consumption habits acceptable by the new residents and by the new users of the neighbourhood (Smith 1996, Beauregaurd, 1986, Ley 1996). At this point, we should underline that gentrification theories were mainly developed in the Anglo-american world. When considering corresponding processes in areas with contextual differences from the theoretical model as regards economic, social and spatial configuration dynamics, attention should be paid the identification, characterisation and analysis of the gentrification processes (Maloutas, 2012). The interpretation of gentrification dynamics should reflect local conditions, in order to allow the particularity of each case to emerge and, ultimately, in order to document the gentrification process.

In the centre of Athens such spatial and social changes have been observed since the 1990s, with a first gentrification example in Plaka, a neighbourhood at the foot of the Acropolis. Through strong state intervention, the urban fabric of the area was listed, buildings were expropriated by public agencies [mainly the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Planning, Environment and Public Works (YPEHODE)] and specific regulations were adopted for building, traffic, and operation of commercial and entertainment activities. As a result of these regulations, households comprising of vulnerable populations that lived in the area until the 1990s were displaced, as were the land uses serving this population and the special (rock/punk) cultures of the previous period. The tourism and entertainment industries were mainly catering to tourists and upper social strata, who bought and renovated neoclassical buildings in the area. To a large extent, the housing stock of Plaka was restored and the area has become a reference point in every Athens guidebook.

The transformations in the areas of Metaxourgeio-Gazi

The spatial and social transformations that took place since the early 2000s in the area of Gazi and Metaxourgeio represent newer trends in the gentrification process in the centre of Athens. Some theatres appeared in Gazi in the mid-1990s and bars also gradually followed suit. The entertainment industry aggressively invaded the neighbourhood and converted it into endless party place following the restoration of the Gas plant and its transformation to the “Technopolis” cultural venue, but especially after the launch of the Kerameikos subway station. Roma families living there were forcibly displaced from low-rise houses with inner courtyards, and were replaced by bars and reinvented tavernas (Alexandri 2005, Tzirtzilaki 2008). The entertainment industry in Gazi was accompanied by an informal market, such as car parking services from bouncer gangs and extortion affecting property rights in the neighbourhood. If one did not accept the offered parking service, they were likely to find their car with serious damage and if one did not accept to change the use of their property they were likely to find it burnt down, as was the case in an old bakery whose owner refused to cede the premises for a new bar.

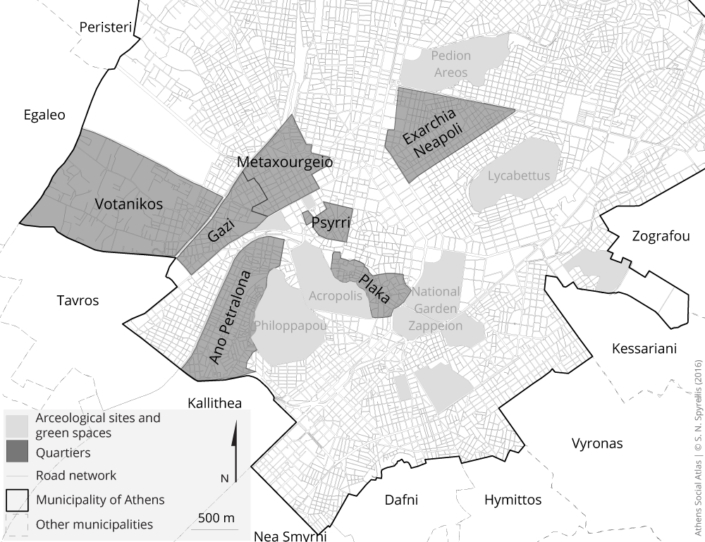

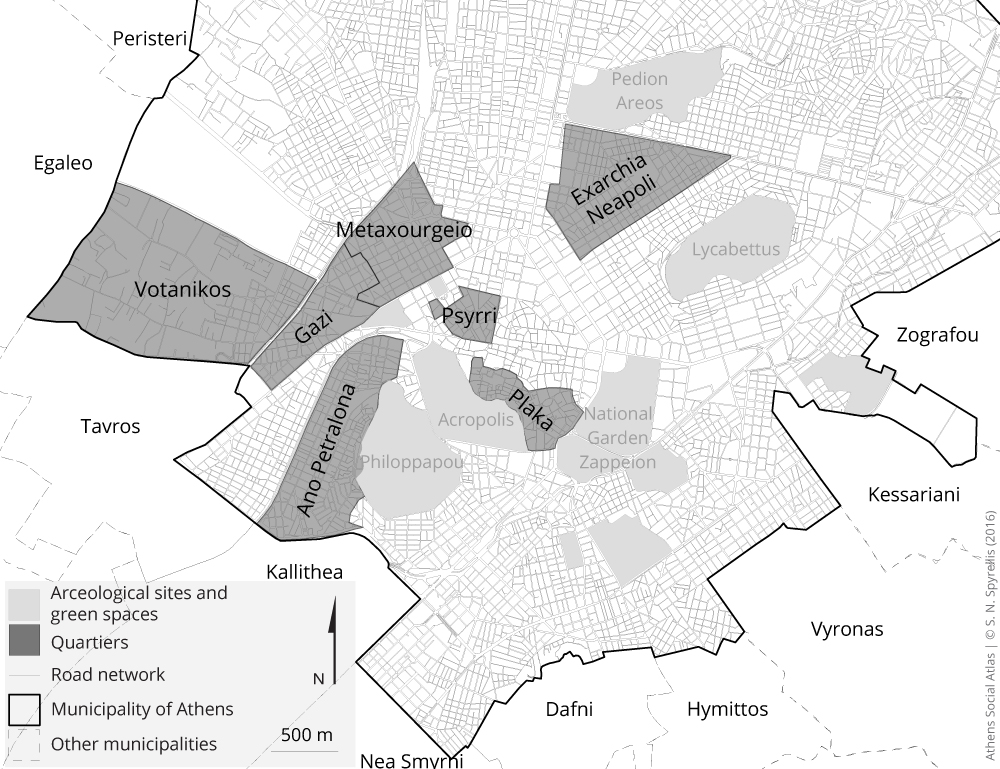

Map 1: The neighbourhoods of the Athenian centre

In the mid-2000s, luxurious newly built structures appeared, promising a new life in lofts in the centre of Athens. As a trend, loft-living was initiated by artists in New York, who rented large open-plan areas of old factories,so-called lofts, and used them as a place for working and living. Their lifestyle and various spontaneous artistic events and parties turned a new form of architectural trend (the loft) into a new market for real estate: designing residences with open spaces in old industrial shells. We should underline that the new buildings in Gazi were not the result of the conversion of old factory areas, but mimiced architectural forms that emerged in New York through the lifestyle of artists and of upper and middle class social strata. However, in Gazi the capital gains from the rapid development of the entertainment industry and its negative impact on the everyday life of the neighbourhood (noise from bars, clubs and modern tavernas, parking and traffic problems, etc.) had an adverse effect on attracting new residents. This, of course, does not diminish the brutality of the displacement suffered by weaker social groups, such as the Roma, or the brutality and threats of the new “masters” of the area against old residents. To this day, for Gazi the term gentrification refers more to new commercial uses of land, rather than residences.

A better gentrification example regarding residences is the area of Metaxourgeio, where gentrification refers to both uses of land and to residences. The spatial and social restructuring process in the area of Metaxourgeio followed a slower pace compared to its adjacent neighbourhood of Gazi. Since the mid-1990s, several households from the upper social classes, having insider information on the future upgrading of the area, rushed to buy and renovate houses, thus managing to place themselves in the market before the formation of a significant rent gap (Alexandri, 2013). At the same time, the area started to attract theatres, which subsequently attracted artists as residents and consumers of new land uses. The fashion of raki drinking and contemporary coffee houses became prominent since the late 2000s, while more eclectic restaurants featuring molecular and ethnic cuisine or wine bars completed the picture of the new entertainment uses developed in the area. New land uses, such as fashion boutiques, organic food shops, pet shops and new hair salons come to serve the needs of the new residents, be they wealthy or bohemian, with artistic interests.

The area of Metaxourgeio also attracted keen investor interest by companies operating in the real estate market. In 2007, the company GEK TERNA built a luxurious gated residential complex opposite to the old factory of Metaxourgeio, with an indoor pool and upgraded security systems. Before the real estate crisis, apartment prices for the complex reached 4,000 Euro per square metre, while after 2008 they dropped by 30%. However, the company, prefers keeping the apartments empty (40%) rather than selling them at a lower price, thus providing a good insight to their profit margin. The company Oliaros, on the other hand, holds 4% of the residential reserve of the area, namely about 65 properties, which it provides for cultural purposes, such as the Remap art exhibition, every two years. During the exhibition period, members of the public are invited to tour the streets and buildings of the area. This sets the conditions for re-mapping Metaxourgeio: the inner courtyards, the view to the city or the Acropolis, the high-ceiling rooms, wooden staircases, marble floors and plaster reliefs on the walls and ceilings frame the Remap exhibitions, which therefore invite aspiring middle class residents. At the same time, the main investor of Oliaros, , founded the civil non-profit organisation “Model Neighbourhood” in collaboration with the wealthiest of the newly installed residents. This organisation puts a claim on the area of Metaxourgeio, in an attempt to impose specific cultural standards through proposals for the redevelopment of the area, cooperation with the Municipality of Athens and various ministries as well as interventions in the built environment.

A result of the new social and spatial dynamics developed in the area of Metaxourgeio is the displacement of Roma, immigrants (both legal and others) older couples, as well as less well-off young residents. Essentially, as in other cases of gentrification, people who cannot respond to the rent rise or do not have the financial income required to purchase the property, are forced to leave by direct or indirect methods. Often, the most vulnerable groups such as immigrants and Roma, are faced with violent practices by the owners, such as power and/or water cuts, to force them to leave a property intended for a new, wealthier owner or tenant. In this manner, weaker groups are shifted to the adjacent areas of Acadimia Platonos and Kolonos, or become homeless. The displacement caused by gentrification is an additional urban problem and raises some serious issues of spatial and social injustice.

Exarchia and Petralona: Gentrification processes?

Similar spatial and social dynamics are to be found in the area of Petralona. The old traditional neighbourhood is turned into an entertainment venue for hipsters, rents remain quite high, weaker households are displaced and replaced by wealthier households. However, the gentrification story in Petralona is somewhat different. Old and new more politicised residents oppose the way space is commercialised, particularly by new uses of nightlife entertainment and the practices developed by night-life entrepreneurs. In response to the arson of the houses of two members of the Petralona Residents’ Assembly and to threats concerning the assembly itself, the residents organised a local movement for the conservation of the traditional character of the area, which in essence opposes the gentrification trends through the new land use and new users. To this day, the example of Petralona is the only case of neighbourhood where there is a movement against gentrification, claiming the right of residents, old and new, to the public and private spaces of the area.

It is no coincidence that many new residents of Petralona are former residents of Exarchia, an area in the centre of Athens, on the southwestern boundary of Pireos Street, which is often described by the media as an “anarchist stronghold” or an “inaccessible area”. Everyday life fully refutes these labels, as it is an area very much loved by people of art, culture and political contestation, ever since the pre-war period, given its proximity to universities, especially before many of them were moved off centre. The spatial and social dynamics in the area hardly support the gentrification theory, as it was never purely, nor mainly, a residential area for the working class, but is characterised by vertical social segregation (Maloutas & Karadimitriou 2001). The rent gap theory, even today, cannot be supported: rents and property prices remain very high even during the crisis because of its history and the political and cultural reputation of the area. However, in recent years, especially on streets near Exarchia Square, some degradation trends are developing, forcing many households to leave the area.

Today, residents of Exarchia, maintaining particular political and cultural concerns, have a special sensitivity to quality of life issues in the neighbourhood.The Municipality of Athens does not always renew the light bulbs or clean local public spaces, while police forces have turned specific points of Exarchia to permanent surveillance spots, providing “safety” through arrests and frequently throwing tear gas in the central square of the neighbourhood. At the same time, especially with the outbreak of the crisis, gangs have emerged in Exarchia, involved in drug trafficking, counterfeit or smuggled goods, the exploitation of immigrants as well as selling “protection” to food and beverage shops. These criminal practices have allowed a kind of “social cannibalism” to emerge. As many residents describe, society turns against the weak links, rather than taking action against the causes that produce and reproduce hate practices. Various collectives have highlighted key issues for claiming and shaping the public spaces of the area affected by delinquent behaviours. They engage in practices of mutual aid, creating solidarity networks against the crisis. The successful operation of the time bank, of the no-intermediaries market, of the solidarity committees and the self-shaped spaces, collective kitchens, bazaars and the choir of Exarchia mean the area is in constant motion. Residents’ collective practices have managed to fight the fear brought about by the austerity conditions imposed through successive Bail-out agreements and neoliberal policies.

Entry citation

Alexandri, G. (2015) Gentrification in the neighbourhoods of the Athenian centre, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/gentrification/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.51

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Αλεξανδρή Γ (2013) Χωρικές και κοινωνικές μεταβολές στην Αθήνα: η περίπτωση του Μεταξουργείου. Χαροκόπειο Πανεπιστήμιο.

- Τζιρτζιλάκη Ε (2008) Eκ-τοπισμένοι, αστικοί νομάδες στις μητροπόλεις. Αθήνα: Εκδόσεις Νήσος.

- Alexandri G (2005) The gas district gentrification story. DISS, Cardiff University. Available from: http://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/1512448/dissertation__2_.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAJ56TQJRTWSMTNPEA&Expires=1469481787&Signature=BV8RPBknMo5%2FV%2BpUkK3mR6l8vmA%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3B filename%3DThe_Gas_District_Gentrificati.

- Beauregard RA (1986) The chaos and complexity of gentrification. Gentrification of the City, London, Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

- Ley D (1996) The new middle class and the remaking of the central city. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press 90(5).

- Maloutas T (2012) Contextual diversity in gentrification research. Critical Sociology, Sage Publications 38(1): 33–48.

- Smith N (1996) The new urban frontier: Gentrification and the revanchist city. London, New York: Routledge.

- Smith N and Williams P (1986) Gentrification of the City. 1st ed. London, New York: Routledge.