Renewing architectural memory: the historic buildings of Neo Faliro

Georgikopoulos Ioannis

Culture, History, Quartiers

2020 | Jan

The architecture of the Neo Faliro suburb of Piraeus began to be dominated by neoclassical and eclectic style buildings from the last quarter of the 19th century. Less known for this feature than the centre of Athens, this neighbourhood was, thanks to its proximity to the sea, and until the first decades of the 20th century, a new summer holiday destination for wealthy Athenian families. Subsequently, the gradual increase in real estate development was linked to flats-for-land based contracts (known as the antiparochi system) with no consideration, in most cases, for the previous constructions. This new development model was influenced by the socio-economic context of the time, as the increase in the number of permanent residents and the subsequent changes in the neighbourhood required buildings that were more functional and adapted to an increasingly hectic lifestyle. This paper aims to demonstrate the uninterrupted presence of the historic buildings of Neo Faliro and to contribute to the broader scientific debate on the management of architectural memory in the contemporary period, and more particularly, on the link between (neo-) classical morphology and Western representations of Hellenism throughout the 19th century. It is of particular interest in the study of the symbolism of the historic buildings of Neo Faliro. The renewal of the local architectural memory, and its relationship with contemporary issues at different levels, may contribute to the understanding of internal contradictions as well as to the necessary paradigm shift.

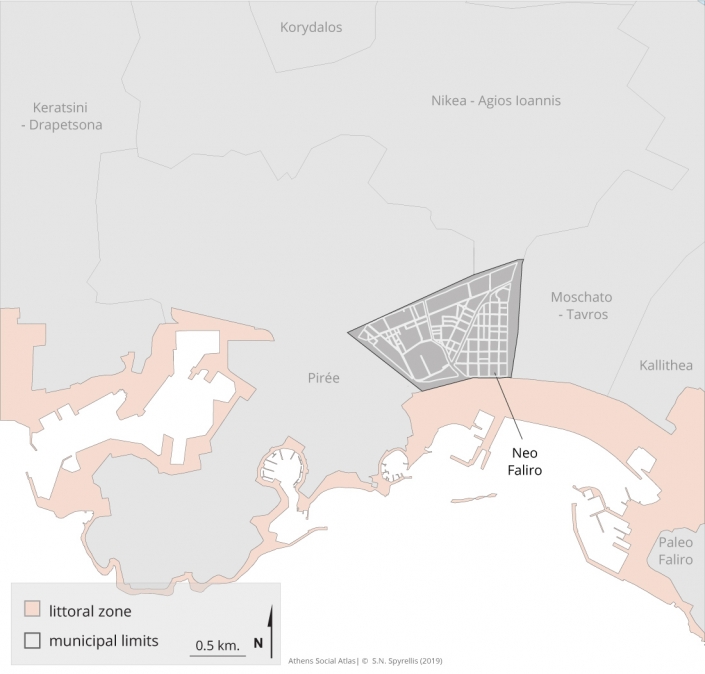

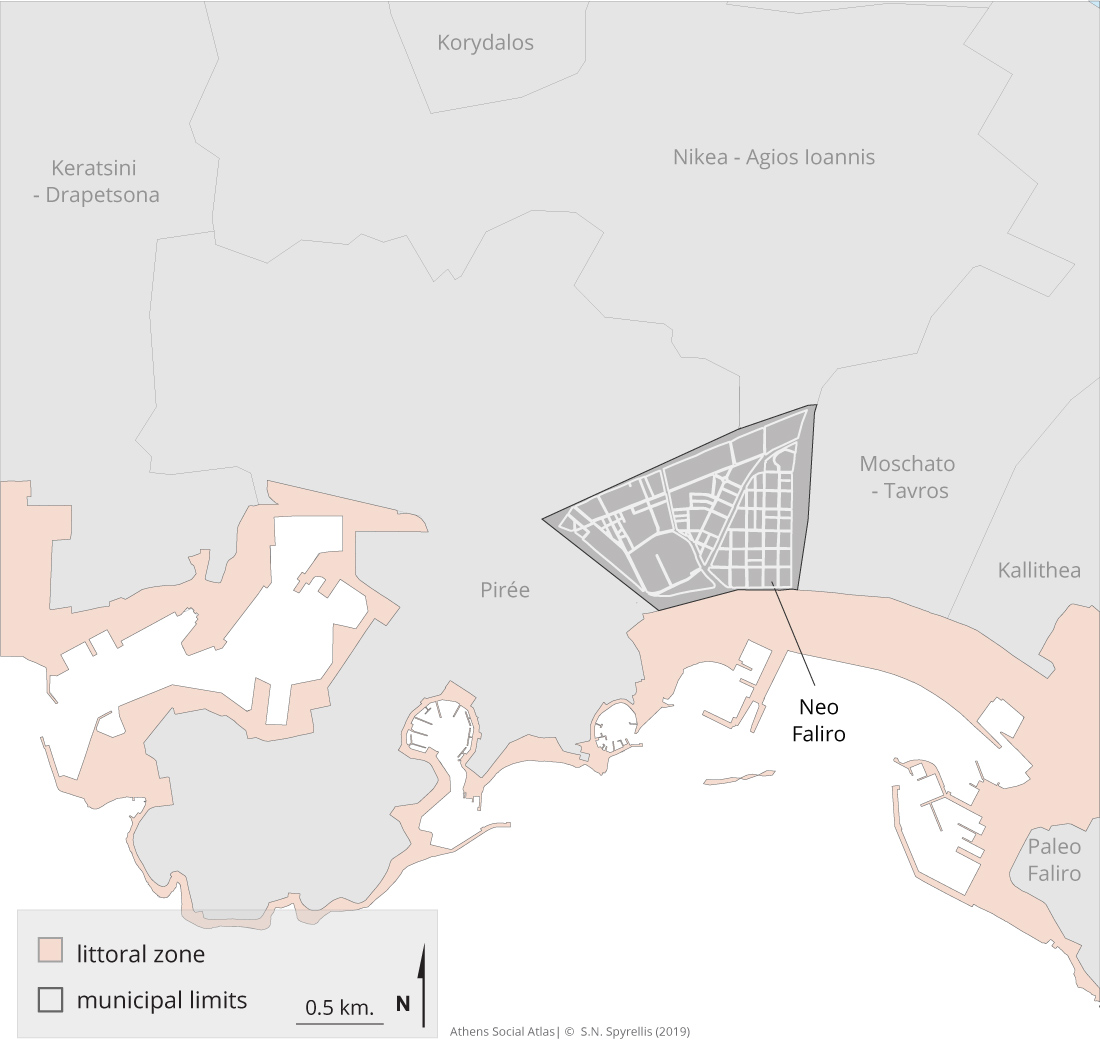

Map 1: Neo Faliro and surrounding neighbourhoods

When Constantinos A. Doxiadis conceptualised ‘Ekistics’ as the Science of Human Settlements, he placed at the centre of his analysis a system of five elements/tools: Nature/Environment, Anthropos, Society, Shells (buildings/dwelling units) and Networks. Seen from different perspectives (economic, social, political, technical and cultural), these contribute to the understanding of the structure, functioning, and evolution of housing units (Doxiadis, 1968). Among these elements, the shells are the material expression of the dialectical relationship between demographic evolution, economic development, socio-historical trajectories and cultural landmarks in the urban, peri-urban or communal setting. These buildings are, moreover, in direct contact with traffic networks, the predominant aesthetic of each era and the degree of resilience of local societies.

Today, historic buildings/shells help us connect tradition to the present as they contribute to our understanding of the pressures on the city over time (economy, cultural ebb and flow, norms and ideas, globalisation) and the city’s capacity to cope with these pressures. From this perspective, the historic buildings of Neo Faliro – a peri-urban node between the centre of Athens and the port of Piraeus – offer a crucial opportunity to explore, in space and time, the identity of the local architectural memory by linking it to broader geopolitical and social issues.

With its back to the sea: the acquired introversion of Neo Faliro

After World War II and the Civil War (1944-1949), the subject of the reconstruction of the country was paramount in Greece. With the help of the Marshall Plan and the economic revival of the mid-1950s (Alogoskoufis, 1995), the steady development of the construction sector helped stabilise the political system and ensure the citizens’ feeling of financial security (the role of ownership and trust in real estate). At the same time, the horizontal mobility of the Greek population (rural exodus) created the need for the rapid building of affordable housing which gradually became associated with phenomena ranging from commercialisation and standardisation to the destruction of the traditional architectural landscape and the severe deterioration of aesthetic quality (Prévélakis, 2000). The Greek cinema of the 1960s illustrated this demand for new post-war housing, in which urbanisation symbolised social ascension and found practical expression in the functional comforts of the condominium [1]. Consequently, Greek building construction in the period between 1955-1967 followed the triptych of stabilisation – urbanisation – urban reconstruction and relied heavily on the process of antiparochi [2].

The changing lifestyles and the introduction of apartment buildings in the urban landscape [3] also influenced, although much later than in the centre of Athens, the peri-urban neighbourhoods, which began, in turn, to modernise while disregarding the aesthetic result. The most significant examples of this are the districts of Kaminia and Neo Faliro, where workers whose jobs were in the industrial area of Peiraios Street, found fertile ground capable of accommodating this change: from the mid-1970s onwards, the antiparochi gradually replaced the traditional detached houses and some historic buildings, thus transforming an entire class of petty-bourgeois into owners. At the same time, Neo Faliro became the new hub between Athens and the port of Piraeus, the latter functioning, from the early 1960s, as a second centre after Athens. This change resulted from internal migratory flows and various geopolitical processes, as well as from the congestion-pollution combination brought on by the increasing number of vehicles in the streets of Athens. One could observe, on the one hand, the arrival of internal migrants and the creation of local communities (paroikies) by Greek islanders [4] in the southern suburbs (Georgikopoulos, 2018a) and, on the other, the reverse trend wealthy families leaving the centre of Athens in favour of the former holiday suburbs, especially from the 1980s onwards.

In this context, Neo Faliro benefited from the resulting economic and cultural activity (retail, industries, businesses, entertainment, restaurants), although the customers and employees increasingly opted to travel by car. However, on the polar opposite, despite notable exceptions in favour of strategic and coherent urban planning [5], a break in the local architectural memory begins to emerge. The development of apartment buildings in Neo Faliro transformed a diverse and multi-purpose neighbourhood into a mediocre suburb. This was the price to pay for the necessary compromise that would restore the socio-political and economic balance within a post-war Greece (World War II, Civil War) in the midst of the Cold War.

The uncontrolled suburbanisation and concentration of internal migrants led to the scattering of activities, increased traffic congestion, the need to renew public transportation, but also to administrative decentralisation and the creation of new jobs at the local level. On the other hand, it also involved thoughtless construction and the emergence of large multi-storey buildings – “small luxury palaces with all comforts” (Μυλωνάκη, 2012) – replacing the historic buildings of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This was a “sacrifice” on the altar of development and necessary demographic and social renewal. From the mid-1970s and especially from the 1980s onwards, the Neo Faliro district underwent the demolition of its old buildings while its inhabitants increasingly favoured the security offered by introversion and architectural oblivion. However, what does this architectural memory consist of? To which socio-historical processes does it relate? Furthermore, through what symbolism does it interact with other geographical scales?

The era of « strategic cosmopolitanism »

Until the interwar period, Neo Faliro was where the Athenian bourgeoisie met the proletariat of Piraeus. At a short distance from the local factories, also called fàbrikes, (such as the AIS electric station, the ION chocolate factory, the CHROPEI, ELAIS, Minerva, IVI, Kerameikos, Indiana and Sarantopoulos factories, the Hellenic Textile Industry etc.) were scattered neoclassical and eclectic style holiday houses, used by wealthy Athenians especially during the summer.

On the seafront, the Baths (Loutrà) – moved from Zéa to Neo Faliro – and the Nautical Club (Nautikos Omilos) were also places where the different social classes met, since the beach of Neo Faliro welcomed both the inhabitants of the various districts of Piraeus and the bourgeois Athenian families. Likewise, the public school was another space of coexistence and assimilation, where students from very different social classes were able to create and maintain essential bonds. This resulted in the incorporation of the historic buildings into the local social fabric, as the children of their owners invited friends and classmates over for various celebrations.

Thanks to the local light industrialisation and luxury tourism (the “Aktaion” and “Grand Hotel de Phalère” hotels, the music and refreshments stand “Tarantella”), the economic development of Neo Faliro held significant appeal and gradually attracted entrepreneurs, workers, as well as the wealthy inhabitants of Piraeus (such as the writer Pavlos Nirvanas, nom de plume of Petros Apostolidis) and retired Athenians as permanent residents. This enriched the local architectural landscape with single and semi-detached houses typical of the neo-historicist style of the inter-war period (Photos 1-3). This trend persisted until the 1960s.

Photos 1-3: Pre-war buildings in Neo Faliro

Source : Ioannis Georgikopoulos

Both the social composition and demographic evolution of Neo Faliro (Table 1) [6] demonstrate the extroversion and open-mindedness that characterised the suburbs as a place of osmosis between very heterogeneous elements, to which had already been added refugees from Asia Minor [7] as well as the descendants and heirs of the owners of some historic buildings (such as the Giannopoulos, Kotzamanoglou, Lorandos, Papaggelis, Farao, Christophi families etc.).

Table 1: Demographic evolution of Neo Faliro

This extroverted character of the suburbs was in line with the situation during the last quarter of the 19th century, when Neo Faliro began to develop and become organised, taking advantage of the growing economic activity in Piraeus after 1870 (Μαλικούτη, 2004). Under King George I, the diversion of the Piraeus-Athens steam locomotive (Official Gazette – ΦEK 18/1869 – Decree on the railway link between the Public Baths of Neo Faliro and the Athens-Piraeus line), intended to facilitate access to the creek of Neo Faliro, paved the way for the emergence of peri-urban architecture. Later, the steam tramway (1887) and then the electric tramway became an alternative mode of transportation for the Athens-Faliro route. The first holiday houses were built starting in the 1880s as meeting places for the bourgeois Athenian families and the intellectuals of the time. A significant example is the mansion of the satirical poet Georges Souris (Photo 4), where writers belonging to the so-called “New School of Athens” (also called the “1880 generation”) organised cultural evenings. At that time, Neo Faliro became a part of the Municipality of Piraeus (1876) and had 242 permanent residents in the 1889 census.

Photo 4: George Souris’s residence in Neo Faliro

Source : Ioannis Georgikopoulos

Up to, and including, the inter-war period, the neighbourhood remained included in the design of urban planning, either with projects for manor house developments on land around the streets following the slope of the Cephissus river (such as the plans of Ludwig Hoffmann for example) or in the form of urban planning studies (such as those proposed by Stilianos Leloudas) with suggestions for the creation of entertainment areas (“Places of the Coasts” – Akton Periochi) which would extend from Tourkolimano to Paleo Faliro (Φιλιππίδης, 1984: 116-120).

The construction of these buildings, along with that of luxury hotels along the seafront (such as the “Aktaion” and “Grand Hotel de Phalère”), was rooted in the classicist tradition while also integrating elements of eclecticism. This synthesis of influences, combinations, and of architectural forms was imbedded in the respect for local realities and the social needs of Neo Faliro: (small-scale) second homes for vacations and entertainment, integrated into a landscape that combines both urban and seaside elements. Today, and despite the general look of abandonment, we can still see representative examples of this mixed architecture, in which High Neoclassicism and Popular Neoclassicism (Photos 5-12) are articulated with polycentric eclecticism (Photos 13-15) and picturesque architecture (Photos 16-17) in a syncretism between the different morphological elements and the local architectural idiom.

Photos 5-12: Representative examples of mixt architecture with elements of popular neoclassicism and high neoclassicism in Neo Faliro

Source : Ioannis Georgikopoulos

Photos 13-15: Examples of eclectic architecture in Neo Faliro

Source : Ioannis Georgikopoulos

Photos 16 & 17: Examples of picturesque architecture in Neo Faliro

Source : Ioannis Georgikopoulos

These forms of peri-urban architecture, as a tangible reference to the past and to European cultural permanence, continued to connect the inhabitants of Neo Faliro with multiple historical scales. From the time of their construction, these buildings were intended for a population connected, practically and symbolically, to Western standards and representations of modernity. For example, Christos Christofis was a migration agent for the French shipping company Fabre Line (Πανδή-Αγαθοκλή, 2001) His home, designed by Ernst Ziller, is still lived in by family members and is an eloquent example of mixed architecture (Photo 18). At the time, the luxury hotels on the waterfront and Ziller’s “little theatre” were aimed more at the pro-European Athenian class (intellectuals, artists, and writers) that were spiritually linked to the West and spent their holidays in Neo Faliro.

Photo 18: Christofis House, construction in natural stone with eclectic framing, built by E. Ziller

Source : Ioannis Georgikopoulos

In turn, the neighbourhood’s historic buildings continue to illustrate the adaptation of Western standards to the Greek context. The influences of eclecticism and particularly the imported (neo-) classical ideal echo the introduction of the territorial model of national homogeneity at the heart of Western modernity during the creation of the Greek nation-state (Γεωργικόπουλος, 2016, Georgikopoulos, 2017), Specifically, neoclassical urban planning allowed, but not without difficulty, the implementation of a strategy of iconographic-symbolic centralisation. The Bavarian administration favoured this and, following the norms of the Westphalian nation-state, it contributed to the imposition of Enlightenment values and distancing with the Ottoman past (Prévélakis, 2017). In this context, referring to the Western conception of Antiquity and its adaptation to the local reality is original, insofar as within this “speaking architecture” (Vaudoyer, 1852) there is a strong desire for westernisation while retaining Eastern elements. Indeed, behind the classical front – a symbol of Hellenicity – one very often discovers a construction that reflects the continuity of pre-revolutionary pre-modern lifestyles: semi-open patios, transitional spaces and outside staircases are very common within many of Neo Faliro’s historic buildings.

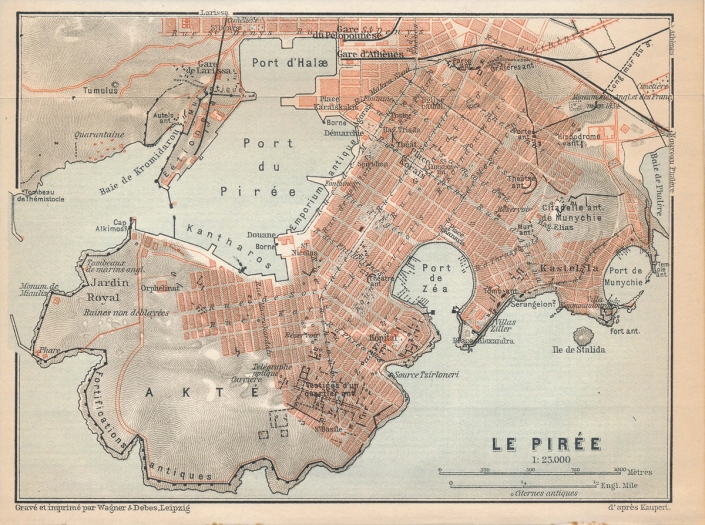

Finally, this mixed architecture maintains its symbolic and cultural relationship with the historical events surrounding the creation of the Greek state and the emergence of the national neoclassical myth, as well as the change in European geopolitical configurations. In this context, one finds a monument erected on the seafront under King Otto in memory of General Georgios Karaiskakis, who was mortally wounded there during the Battle of Phalerus (1827) during the Greek Revolution. Moreover, bibliographical sources and information gathered in situ show the existence of a Franco-British cemetery and a monument-ossuary erected within its walls (Carte 2) in memory of the victims of the cholera epidemic buried during the Franco-British blockade/occupation of the port of Piraeus in the Crimean War (1853-1856).

Map 2: Piraeus in the early 20th century. On top at the right, one notices the monument and the French-British cemetery (« Monument of the English and the French, cemetery »)

Source : Baedeker K (1909) Greece. Leipzig : Karl Baedeker Publisher (4th ed.)

Thus, the Neo Faliro neighbourhood manages to combine the flow of urban architectural typo-morphologies with different geo-historical levels and offers an adequate and relevant framework that allows one to study the architectural and socio-economic evolution of the Greek state by drawing on the “cultural reserve” of the contemporary city. At this point, a crucial question arises: how can this local architectural memory be enhanced in order to alter historical and cultural characteristics and renew social cohesion in the contemporary context?

Reconnecting to the open horizon

The preservation and renewal of architectural memory and heritage is a valuable political asset since it inspires a strong sense of belonging to the city through tangible spatial and temporal continuity. Moreover, these processes are potentially more economically profitable than superficial tourism developments and uncontrolled construction, because durability and continuity become significant comparative advantages which underline the quality of the country’s tourism assets. However, they may also strengthen social cohesion, since the feeling of belonging to a spatio-temporal continuity helps create links of local solidarity between inhabitants, links which can absorb or even prevent tensions and conflicts on several levels.

The process of enhancing the natural and architectural potential takes several paths that interact complementarily. Rethinking and revaluing the local architectural memory thus enables one to go beyond the double cultural dependence of Neo Faliro on the centres of Piraeus and Athens (private schools, theatres, universities) and move towards a symbolic rallying between the spaces. These affinities may subsequently lead to renegotiating or revising the administrative roles of the State: effectively linking geo-historical places and levels at the socio-symbolic level implies giving meaning to an organised and effective administrative and fiscal decentralisation.

Also, the connection to the sea and to the architectural symbolism of Piraeus and Athens (which also have a number of historic buildings) may, in the long term, once again give Neo Faliro the traits of an “outward suburb” whose dynamism will be strengthened by the incorporation, integration and interaction of different groups of population. That being said, the renewal of the architectural memory of Neo Faliro, along with its geographical location (between the seafront and an industrial area) and the entrepreneurial spirit of the new generation of inhabitants, seems to create the conditions for the emergence of new levers of cohesion. Indeed, while those who are in their sixties and older remain more attached to their small place of origin (town, village, island) than to their place of residence, their children and grandchildren seem to have already integrated the reference to their native neighbourhood. With the emergence of this second and third generation, a large part of the local population is beginning to develop strong ties to Neo Faliro, while also grasping the need to renew and reclaim its architectural and patrimonial assets against a backdrop of geo-historical references.

The economic aspect of these processes is also important and will benefit both from the existing public transit network and the one being built (extension of the bus, train, and tramway lines, etc.) The combination of cultural and quality tourism (the dialectic between the local architectural heritage and various historical levels) together with the creation of areas for housing and cultural activities (scientific conferences, theatre performances, concerts, speeches, museums) as well as the linking of this complex with different parts of the Athenian coast (such as Voula and Vouliagmeni) can revitalise Neo Faliro thanks to the creation of new jobs and the interest of European, (Greek-) American and Chinese cultural tourists. Ideally, this perspective will result in connecting the neighbourhood with the global spiritual, intellectual and financial networks that Athens and Piraeus already enjoy.

In this way, the political-administrative, symbolic, and economic revaluation and strengthening of the functions and processes described above link the local to the national, European, and global levels through circulation and mobility. Moreover, they can also create the conditions for a better life and working environment at the local level for newcomers (refugees for example) in contrast to the instability and socio-economic insecurity of the centre of Athens (Georgikopoulos, 2018b).

Thanks to its geo-historical and architectural potential, Neo Faliro is likely to become an economic and cultural oasis between Athens and Piraeus, between stato-national centralisation and Mediterranean landmarks. The return of Neo Faliro to the open horizon is a process that taps into the capital of diachronic lost memory in a way that allows symbolic themes to interact with urban renewal projects and architectural intervention. This shift from a technocratic approach to a spiritual/symbolic, and, therefore, political, framework requires several synergies. It involves initiatives from civil society, active cooperation between the different actors, an enthusiastic and dynamic spirit on the part of the new generations and creative, innovative and determined political leadership. In this context, and despite problems and delays that are difficult to understand, recent initiatives (creation and activities of the Cultural Centre of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, projects of the regional administration, renovation of the Delta Faliro-Cephissus area, mobilisation of the owners of historic buildings), as well as the bicentenary of the Greek Revolution (1821 – 2021), may initiate this change of direction, both practically and symbolically. The historic buildings/shells of Neo Faliro, the monument of Karaïskakis and their political-historical references are a constant reminder of the geopolitical and cultural innovation of the 19th century and provide the impetus for a renegotiation of the architectural and cultural memory on several levels. This will allow the unavoidable blending to lead to an indispensable reshaping.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Professor Stamatina Malikouti from the Department of Civil Engineering of the University of West Attica for her invaluable help

[1] The two movies «Θα σε κάνω βασίλισσα» (I will make you a Queen, 1964) and «Η δε γυνή να φοβήται τον άνδρα» (And woman will fear her husband, 1965) demonstrate eloquently the difficulties, compromises, alliances and counter-alliances that derive from the dreams of Greek society for a better life based on material gains and set within the urban fabric.

[2]For an in-depth analysis of the term see Prévélakis 2000.

[3] One must mention law 3741/1929 (Official Journal/ ΦEK A’ 4) of « Horizontal Ownership », considered to be the precursor of modern apartment buildings

[4] For example, the Dodecanesian community of Athens and Piraeus. The Dodecanese Archipelago was the last territory attached to the Greek state (Treaty of Paris of 1947)..

[5] The elaboration, by the Ministry of Land Planning, Housing and the Environment under Stéphanos Manos in 1977, of a new strategy encouraging the control of urban planning prescriptions and upgrading the role of architectural heritage did not have time to show its true potential. With a few exceptions, the Greek state’s urban planning policies continued to be instrumentalised as a pre-electoral means of buying votes (most often through the increase of the land use coefficient).

[6] Table 1: Demographic evolution of Neo Faliro. Source: Greek Statistical Agency (ELSTAT) and Greek National Printing Agency. Regarding the number of inhabitants of Neo Faliro, the available targeted data are based on the censuses of 1889 (Municipality of Piraeus), 1920 (Municipality of Piraeus), 1928 (Municipality of Neo Faliro), 1940 (Municipality of Neo Faliro), 1951 (Municipality of Neo Faliro) and 1961 (Municipality of Neo Faliro). From 1968 the neighbourhood is definitively incorporated into the Municipality of Piraeus. There ceased to be separate statistical data for Neo Faliro after the 1971 census. The population growth that marked the censuses of 1920 and 1928 is due to the various decrees of modification and the multiplication of building permits (now town planning permits) granted during the first quarter of the 20th century, as well as to the settlement of refugees from Asia Minor (Mikrasiates) in Neo Faliro in 1923.

[7] A small (but important for the situation of the neighbourhood) number of refugees were settled in the state housing estate created for this purpose in Souda of Neo Faliro (behind the current Statistical Agency, which connects the industrial zone on Peiraios Street with the “Georgios Karaiskakis” stadium). However, when they arrived, the refugees found a dirty and decrepit space which from the end of the 19th century had served to accumulate sewage from the same factories where they were going to be employed. The odonyms of the Souda district of Neo Faliro (Asia Minor Street, Kardasis Street, Smyrna Street, Nea Ionia Street, Mouratis Street, Emmanouilidis Street) highlight and hark back to its strong migratory past.

Entry citation

Georgikopoulos, I. (2020) Renewing architectural memory: the historic buildings of Neo Faliro, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/historic-buildings-of-neo-faliro/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.93

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Γεωργικόπουλος Ι (2016) Η Εθνική Κατασκευή στα Δωδεκάνησα. In: Γεωργαλίδου Μ και Τσιτσελίκης Κ (eds) Γλωσσική και Κοινοτική Ετερότητα στη Δωδεκάνησο του 20ου αιώνα. Αθήνα: Παπαζήσης, pp. 75-96.

- Μαλικούτη Μ (2004) Πειραιάς 1834-1912. Αθήνα: Πολιτιστικό Ίδρυμα Ομίλου Πειραιώς.

- Μυλωνάκη Α (2012) Από τις Αυλές στα Σαλόνια: Εικόνες του Αστικού Χώρου στον Ελληνικό Δημοφιλή Κινηματογράφο (1950-1970). Αθήνα: University Studio Press.

- Πανδή-Αγαθοκλή Β (2001) Η Ιστορία του Νέου Φαλήρου Μέσα από τους Δρόμους του. Αθήνα: Όμβρος.

- Φιλιππίδης Δ (1984) Νεοελληνική Αρχιτεκτονική. Αθήνα: Μέλισσα.

- Alogoskoufis G (1995) The Two Faces of Janus: Institutions, Policy Regimes, and Macroeconomic Performance in Greece. Economic Policy 10(20): 147-192.

- Doxiadis CA (1968) Ekistics: An Introduction to the Science of Human Settlements. London: Hutchinson.

- Georgikopoulos I (2017) Quand l’Alisverissi Transfrontalier Fait Vivre : Castellorizo et Kaş Face aux Crises. L’Espace politique 33(3). Epub available at: http://journals.openedition.org/espacepolitique/4437. DOI: 4000/espacepolitique.4437.

- Georgikopoulos I (2018a) Géopolitique du Dodécanèse. Thèse de Doctorat, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, France.

- Georgikopoulos, I (2018b) De l’Accueil des Réfugiés à la Gestion des Migrations. Les Îles du Dodécanèse : une Zone Tampon à Fort Potentiel entre la Grèce et la Turquie. Anatoli 9 : 95-107.

- Prévélakis G (2000) Athènes : Urbanisme, Culture et Politique. Paris : L’Harmattan.

- Prévélakis G (2017) Qui sont les Grecs ? Une Identité en Crise. Paris : CNRS éditions.

- Vaudoyer L (1852) Etudes d’Architecture en France. Le Magasin Pittoresque 20(49): 388.