In the shadow of the welfare state crisis: Visible and invisible homelessness in Athens in 2013

Arapoglou Vassilis|Gounis Kostas

Housing, Politics

2015 | Dec

This paper [1] presents data from primary research (Arapoglou & Gounis 2014) [2] conducted in 2013-14 to map different forms of homelessness in Athens and to update the data of pre-crisis attempts to record homelessness (FEANTSA 2012, Sapounakis 2006). Twenty-five organisations responded to the survey questionnaires. As a result, 77 implementation actions were recorded that directly address the needs of more than 115,000 persons who experience acute forms of poverty and homelessness. The survey included the largest institutions operating dormitories and hostels, as well as an array of smaller organisations. The majority of respondents were NGOs, but the most significant public agencies under the supervision of the National Centre of Social Solidarity as well as the shelters of the two largest municipalities (Athens and Piraeus) also took part.

Hopper’s (1991) homeless housing taxonomy, adapted to the conditions of Athenian reality, was used. Hopper’s taxonomy has significant advantages in accurately representing the different forms of insecure or unfit housing, which result from two main conditions. First, unemployment and the reduction of income from work has a direct impact on the survival of households and on their access to housing. Second, the debt crisis evolved into a crisis of the welfare state, which shrunk dramatically due to debilitating austerity policies. This shrinkage affected income transfers to households by the state as well as access to health and social care services. The changes during the 2010-2013 period meant that public services were cut back and replaced by voluntary or charitable activities focusing on temporary relief for the poor and homeless. The network of civil society bodies that currently caters for the most vulnerable populations has been internationally termed as the “shadow state” (Wolch 1989). The shadow state has contradictory aspects, as individual organisations sometimes adapt their practices to neoliberal choices and sometimes dispute them (Cloke, May & Johnsen 2010, Keil 2009, Peck 2012). First, practices of social solidarity are reinforced and change in bureaucratic or closed institutional structures is expedited, but on the other hand the victims of state neglect and repression do not receive constant care and the organisations that have adapted to the requirements of their funders (the state or major sponsors) are the ones to benefit.

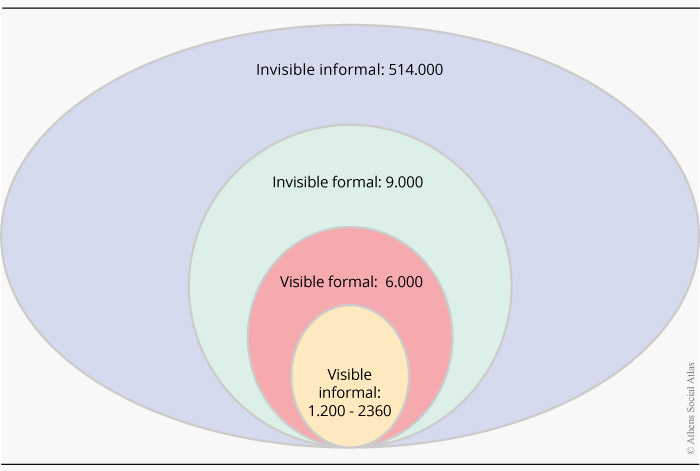

Figure 1 below shows estimates for different categories of homeless and their living conditions in 2013 in the greater metropolitan area of Athens. The estimates were derived from primary research conducted by the authors and from secondary sources.

Figure 1: Landscapes of homelessness in Athens

Source: Primary research by the authors and secondary data analysis

Invisible informal homelessness: poverty and housing insecurity

Invisible informal homelessness refers to households not living in privately owned premises and experiencing poverty and exclusion according to Eurostat’s definition. This includes households that do not own a house and either their income is under the poverty line or all adult members are unemployed or underemployed or experience conditions of housing deprivation. Overall, we estimate that 13-14% of the population in Attica, or approximately 514,000 people, including 305,000 Greek and 209,000 foreign nationals, currently live in such conditions. This estimate corresponds to what is defined as “worst housing conditions” in the US and is used to prioritise allowances and to set up prevention policies. The number refers to those facing extremely difficult conditions, which significantly increase the risk of finding themselves on the street if any additional aggravating factor emerges (e.g. major health problem, eviction, friends unable to provide accommodation, loss of persons supporting them, disruption of family or interpersonal ties, etc.).

The magnitude of invisible and informal homelessness has increased dramatically. The population living in such conditions in Athens has doubled since the start of the crisis. This increase is due to the rapid rise in poverty and unemployment rates which in turn affected specific parameters of housing insecurity such as the inability of households to cover their housing costs, particularly rents, overcrowding in small dwellings and housing unfitness. These trends also affected deprivation in densely populated urban centres across the country. Indicatively, for 2013, according to Eurostat’s on-line database on population and living conditions: the housing costs of poor households accounted for 71% of their disposable income, 69% of poor households delayed the payment of rents, water or electricity bills, 45% of poor households lived in overcrowded conditions. Moreover, poverty risks, unemployment and homelessness are unevenly distributed among Greek citizens and foreign nationals. For example, the rate of poverty and exclusion in 2013 was 32.6% for Greeks and 68% for foreigners.

Invisible formal homelessness: re-institutionalisation and confinement

Invisible formal homelessness includes the use of unsuitable accommodation in public institutions and residential care (hospitals, mental institutions, homes for elderly poor, child care institutions); containment or an unjustified extension of stay in detention centres and prisons in deviation to their primary function or discharge from said institutions without having secured permanent accommodation. Utilising a variety of secondary sources and primary evidence, we estimated that 9000 people subsist in such spaces located in the area of Athens. Our informants reported abusive arrests during the extensive police operations of “XENIOS DIAS” and unacceptable conditions in the detention centres for undocumented immigrants. They have also reported overcrowding in psychiatric rehabilitation units, unplanned merging of psychiatric hospitals and transfer of patients to private units – thus burdening their families, increasing applications of accommodation in child care and psychosocial rehabilitation units due to financial hardship.

These practices towards the mentally ill, pose serious obstacles to the development of community mental health structures and focus psychiatric reform on privatisation and re-institutionalisation at a local level. Thus, the considerable experience of the institutions that played a key role in the previous decade in developing housing structures for psychosocial rehabilitation and community care, is now ignored. Moreover, the transfer and “confinement” of undocumented immigrants in holding cells and detention centres undermine the efforts of humanitarian organisations to offer housing assistance to asylum seekers and refugees who first appeared in Greece in the early 2000s..

Visible and formal homelessness: emergency and supported housing

During the past decade, housing assistance for the homeless was limited to short-stay hostels that were mostly operated by local government or public welfare institutions. Today, two new types of interventions with diverging philosophies have emerged, in which NGOs play a key role. Local authorities, despite their political rhetoric, play a secondary role. The services and shelters currently provided by public agencies are minimal. Private companies and charities are the most vital source of funding for NGOs and for municipal authorities. The average private funding of the projects recorded is 49% and the total number of those receiving any kind of housing assistance was almost 6,400 people.

The first type of interventions, which is the majority, follows the logic of ‘emergency’ assistance and includes night shelters; day centres for the homeless; hostels for unaccompanied minors and women as well as reception centres for asylum seekers and refugees. The number of guests in short-stay accommodation in 2013 amounted to about 1,700 people (almost equal numbers of Greeks and foreigners). The primary research recorded an increase of up to 40% in guests in dormitories and hostels since 2010. The average increase in demand for housing assistance from 2010 to 2013 is almost 60%.

The second type refers to forms of supported housing and targeted prevention in the community, by allocating apartments and providing housing benefits to vulnerable groups. However, the instability of private financing and the strict conditions and duration of support reduce the effectiveness and, most of all, degrade the preventive and communitarian nature of such interventions. In 2013, there were 4,700 beneficiaries (3,600 Greeks and 1,100 foreign nationals).

Dormitories and “emergency” structures were created by the Ministry of Labour with EU funding. This programme has established dormitories, day centres, food banks, social pharmacies and grocery stores. Dormitories offer a temporary solution for many homeless turned down by short-stay hostels, due to the strict admission requirements, but still do not prevent housing instability.

Photo 1: Entry in an NGO-operated Day Centre

Source: K Gounis 2014

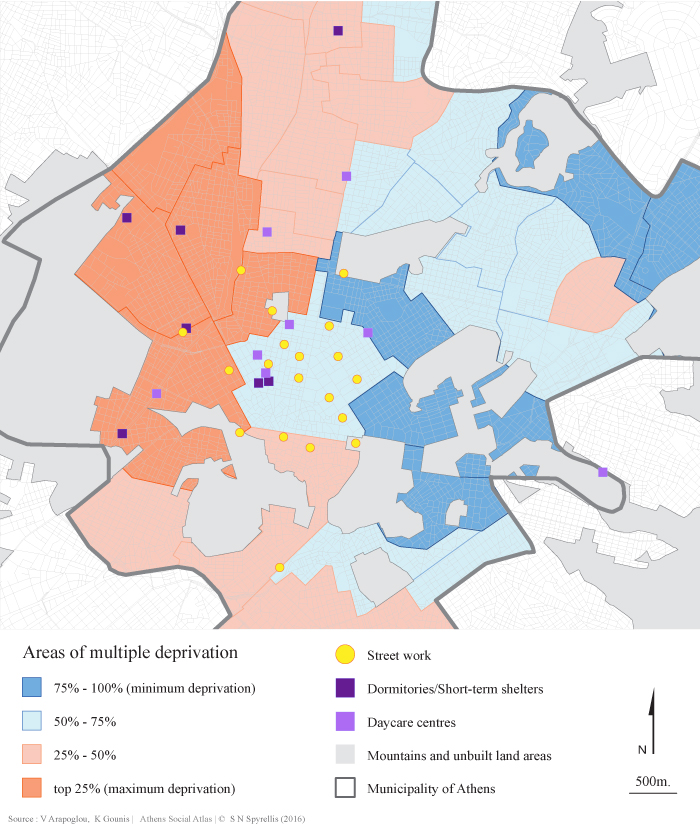

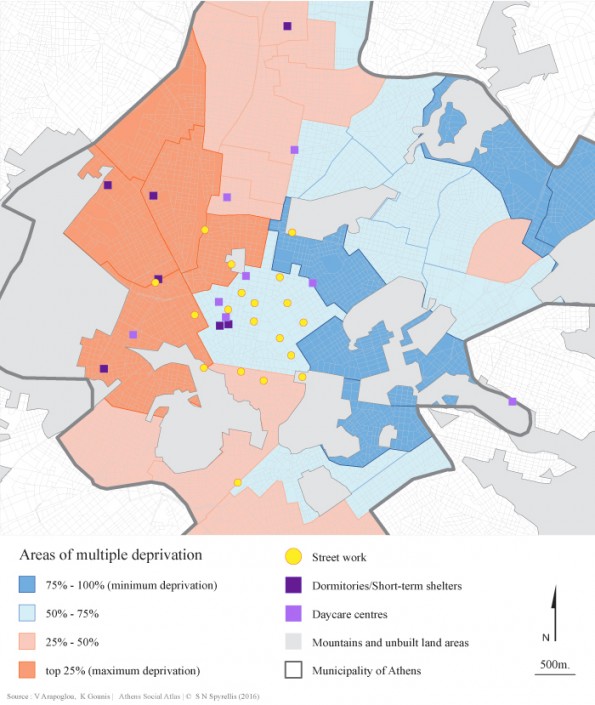

A multitude of projects are often implemented in the same place and serve a variety of people depending on gender, ethnicity or age, often portraying the multicultural landscape of the central areas of Athens in a single building (Photo 1 and Map 1). A significant aspect of the operation of Day Centres is that they don’t only attract the “street homeless” but also a wide array of the invisible poor in the city centre and facilitate their search for healthcare services. The NGOs covered by our survey serve more than 110,000 needy and uninsured individuals in the metropolitan area of Athens. According to data released by the Church of Greece and the Athens Medical Association, the total number of those individuals is about 200,000 people.

The temporary nature of the assistance, the lack of coordination, resources and expertise create atypical practices that lead served individuals, who have been deprived of their rights, on a long and uncertain journey.

Map 1: Visible and invisible homelessness in Athens [3]

Source: Investigation by the authors, interviews and desktop research

Visible informal homelessness: immediate assistance and “clean-ups”

The number of people living in the streets can be only measured using special approximative measurement methods. Therefore, the estimate of 1,200-2,360 persons derives from reports of street workers and from the registers of day centres operating in Athens and Piraeus. This number would have been higher if the occasional stay of drug users in public spaces had been taken into account. Street workers reported an increase in the number of homeless people for 2011 and 2012. However, three organisations agree that in the central areas of Athens, the number of homeless people did not increase during 2013, due to the operation of new dormitories and intensified policing. It is noteworthy that, compared to the previous decade, actions on the street level have increased and have been adopted by bodies that simply hosted the homeless in the past. Figure 2 shows popular street work points in Athens, near newly established day centres but mainly in symbolic points providing high visibility. Obviously, operations to “clean-up” public spaces and to offer assistance on the street are contradictory practices.

In conclusion,during the crisis, the significantly increased visible homeless population found temporary relief in various shelters and direct social assistance services. It seems that flows from insecure housing conditions to the street are not as widespread as assumed by the general public, either because of enhanced informal social solidarity practices or because of the “clean-ups” of public spaces. However, the increase in the need of the invisible poor is unprecedented by European standards. It created a demand for comprehensive support to which the welfare system responded in an insufficient and fragmented manner, by transferring responsibilities – without resources – to civil society.

[1] Data processing and mapping by Dimitra Siatitsa, PhD candidate at the NTUA.

[2] The research was conducted with the assistance of the Hellenic Observatory at the LSE and the National Bank of Greece. The views of the document’s authors do not necessarily reflect the views of the research funders. (Arapoglou V., Gounis K., Siatitsa D., 2015, Revisiting the concept of shelterisation: insights from Athens Greece. European Journal of Homelessness Volume 9.2, pages 137-57)

[3] The multiple deprivation of the invisible poor has been recorded for the Municipality of Athens using data of the Eurostat Urban Audit for 2005.

Entry citation

Arapoglou, V., Gounis, K. (2015) In the shadow of the welfare state crisis: Visible and invisible homelessness in Athens in 2013, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/homeless-and-shadow-state/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.29

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Arapoglou V and Gounis K (2014) Caring for the homeless and the poor in Greece: Implications for the future of social protection and social inclusion. Athens. Available from: http://www.lse.ac.uk/europeanInstitute/research/hellenicObservatory/CMS pdf/Research/NBG_2013_Research_Call/Arapoglou-Gounis-(PROJECT-REPORT).pdf.

- Arapoglou V, Gounis K and Siatitsa D (2015) Revisiting the Concept of Shelterisation: Insights from Athens, Greece. European Journal of Homelessness 9(2): 137–157. Available from: http://www.feantsaresearch.org/IMG/pdf/arapoglou-gounisejh2-2015article6.pdf.

- Cloke P, May J and Johnsen S (2010) Swept up lives: re-envisioning the homeless city. 1st ed. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

- FEANTSA (2012) Monitoring Report on Homelessness and Homeless Policies in Europe. On the Way Home? Brussels. Available from: http://www.feantsa.org/spip.php?article854.

- FEANTSA (2006) Fifth Review of Statistics on Homelessness in Europe. Brussels. Available from: http://www.feantsaresearch.org/IMG/pdf/2006_fifth_review_of_statistics.pdf.

- Hopper K (1991) Homelessness old and new: The matter of definition. Housing Policy Debate, Routledge 2(3): 755–813. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10511482.1991.9521072.

- Keil R (2009) The urban politics of roll with it neoliberalization. City, Taylor & Francis 13(2–3): 230–245.

- Peck J (2012) Austerity urbanism. City, Routledge 16(6): 626–655. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2012.734071.

- Wolch JR (1989) The shadow state: transformations in the voluntary sector. 1st ed. In: Wolch J and Dear M (eds), The power of geography: How territory shapes social life, New York: Routledge, pp. 197–221.