Infrastructures of social integration and refugee settlement in Athens

Arapoglou Vassilis|Mantanika Regina|Spyrellis Stavros Nikiforos|Κourachanis Νikos

Ethnic Groups, Housing, Politics

2024 | Jan

Research framework: urban infrastructures for the reception and integration of refugees

This article presents the main findings of the research project “Inclusive Cities” funded by the Special Account for Research Funds of the University of Crete [1]. Data were collected from three sources: the 2011 national population census, snapshots of available places and beneficiaries of the ESTIA project during 2018 [2], UNCHR’s management reports on Refugee Reception Facilities, and primary research on service providers to asylum seekers and refugees. The geocoding of the data enabled the mapping of the relevant services and the development of spatial analysis indicators. This was followed by three workshops with researchers, representatives of UNHCR, local government, NGOs and their staff which explored how the experience and lessons learned from the ESTIA project were used to shape future reception and integration policies.

The theoretical argument of this effort is the recent approaches that constitute the so-called ‘shift towards infrastructure’ in urban studies, which consider infrastructure as socio-technical systems produced through material, social and symbolic practices (Amin, 2014). This new perspective has informed international studies on the reception and integration policies of refugees in urban environments and the impact of relevant initiatives of the European Union and international organisations such as UNHCR (Felder et al, 2020; Hanhörster & Wessendorf, 2020; Meeus, Arnaut & Van Heur, 2019). These studies bring back the debate on the importance of arrival areas in cities as starting points or stations in the integration process, highlighting new issues that emphasise the implications of locating different types of infrastructure in central, suburban or peri-urban areas.

The creation and installation of reception infrastructures in Greek cities

Infrastructures are collective means of networking that are constantly being expanded and maintained, transformed or shrinking in line with the pace of urban development and their response to global changes. The ‘great summer of 2015’ marked a change in the role of Southeast European cities positioned on the new migration routes from the Middle East. The closure of the Balkan route, and the “EU-Turkey statement” in 2016, marked a turning point for the Greek state’s reception policies and contradictory efforts to adapt to international humanitarian protection norms (Mantanika & Arapoglou, 2022). The reception system rapidly expanded to include four types of residency infrastructure:

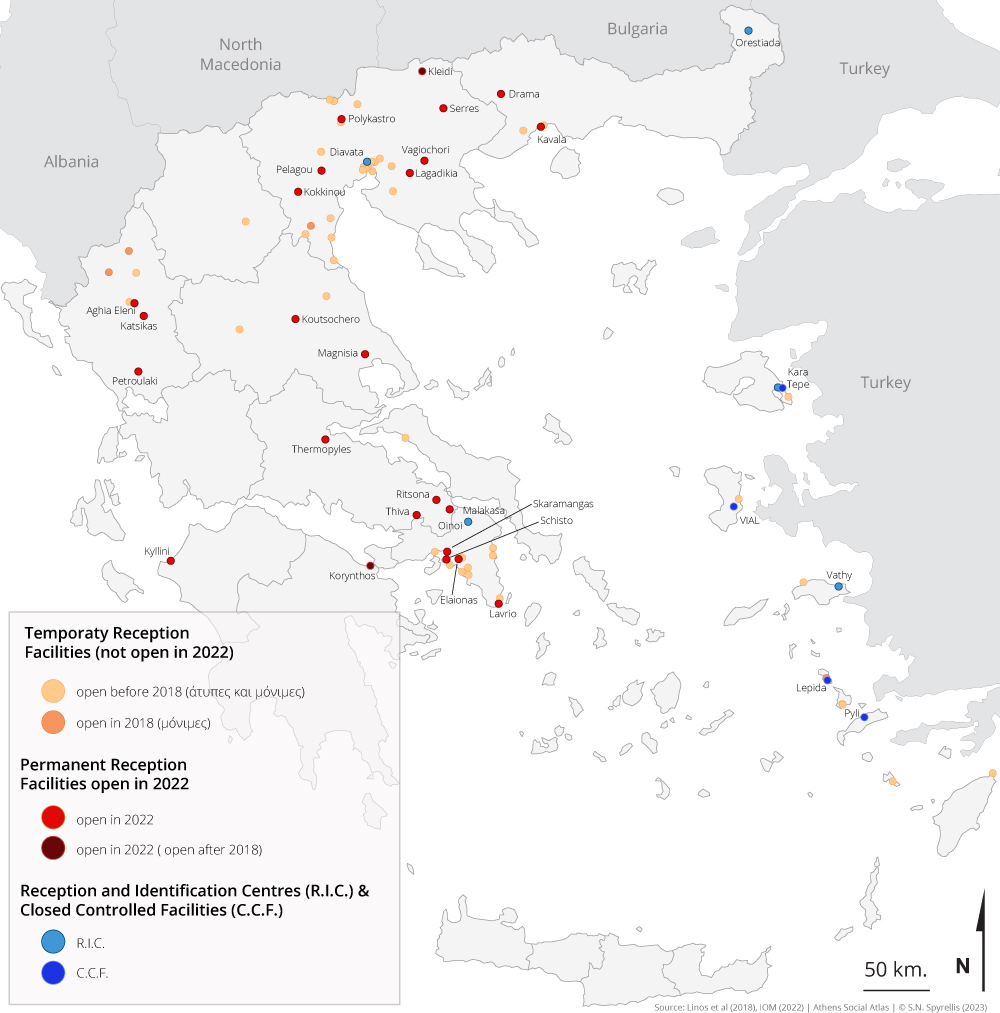

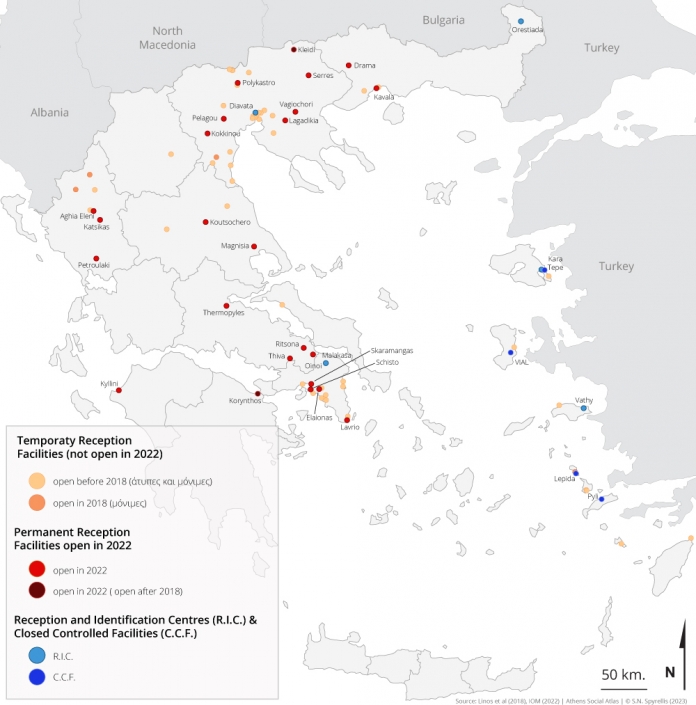

First, reception and identification units for asylum seekers were established on five Aegean islands (Chios, Lesvos, Samos, Leros, Kos) where overcrowding, poor hygiene and housing conditions and lack of access to goods that meet basic human needs were prevalent (Kourachanis, 2018b). Second, ‘open’ Temporary Reception Facilities were created in mainland Greece (‘Camps’), which from informal and temporary forms of accommodation acquired characteristics of permanence under the infeasibility of long-term planning (Map 1).

Map 1: Location of Temporary Reception Facilities (informal and permanent), Reception and Identification Centres and Closed Controlled Facilities 2018 – 2022

Source: Linos et al (2018), IOM (2022)

Thirdly, urban accommodation in apartments, hotels and other buildings in various cities in Greece were set up through the ESTIA programme and, fourthly, rent subsidy and social support actions for the recognized refugees followed through the HELIOS programme from 2019.

ESTIA (Emergency Support to Integration and Accommodation) (2017-2022) was a programme for housing vulnerable asylum seekers in social housing in urban areas under the auspices of UNHCR, funded by the EU and implemented by municipalities and NGOs. It was framed by a cash assistance allowance at the minimum guaranteed income level and social suport actions. Its initial design in 2015 (called the ‘Accommodation and Relocation Programme’) was oriented towards short-term accommodation of candidates for relocation to other EU countries. The change of the programme’s target group was carried out without corresponding social adjustments and integration tools resulting in a continuous increase of inputs without noticeable outputs (Kourachanis, 2018b; Papatzani et al., 2022). In the period 2020-2022 the management of ESTIA was transferred to the responsibility of the Greek state, at which point its operation was terminated.

The framework for the development of social assistance for recognized refugees was attempted through the HELIOS programme from 2019. This was a rent subsidy and integration support actions for recognized refugees that expanded the group of beneficiaries of housing support but replicated the weaknesses of ESTIA (Kourachanis, 2022b). The inadequacy of social benefits forces refugees to seek support from migration networks or to be channeled into undeclared work channels until they move to the European country they wish to settle in. It is therefore a programme that ultimately serves to prolong the stay of refugees in a transit country, such as Greece, rather than social integration in that country (Kourachanis, 2022b).

The spatial pattern of reception infrastructures in the metropolitan region of Athens

The location of these infrastructures in large cities and metropolitan centres was aimed at improving the living conditions of displaced persons and enhancing the prospects of social integration of those who would remain in the country through their dispersal and their interconnection with social services in the urban fabric.

The following analysis uses data from three sources: the 2011 population national census, the ESTIA programme and reports from UNCHR refugee reception centre management (Table 1).

Table 1: Ranking of main nationalities in Athens, population census and housing programmes

Source: ΕΚΚΕ-ΕΛΣΤΑΤ,2015; UNHCR-ESTIA,2018; UNHCR,2018

Regarding the ethnic composition of Athens, groups from Eastern European countries dominate the urban area with Albanians representing almost 50% of non-Greek nationals, followed by Romanians (4.9%), Bulgarians (4.5%) and Georgians (2.9%). The Pakistani community is the only exception to this pattern, representing almost 6% of foreign nationals. The ethnic composition of both the ESTIA program and the ethnic composition of the Centers, as expected, show significant similarities incorporating individuals from the Middle East (Syria and Iraq) or the Broader Middle East (Afghanistan). We note that in 2011 the nationalities associated with the migration wave had already established small communities in Athens. Certainly their presence was not numerous since they ranked between 15th and 30th with Syrians being the most important group among them, representing 1.4% of the total foreign population. As shown in Table 1, if we compare the 2011 census with the two programs, in absolute numbers, we can see that these communities are significantly strengthened. Their presence increases, compared to 2011, by at least 50% (Syria +120%, Afghanistan +91%, Iraq +90%, Palestine +58% and Iran +50%). Moreover, the influx of displaced migrants together with the outflow of migrants from the Balkans and the shrinking population may have had a stronger impact than those reflected in the estimates of the indicators in the current study.

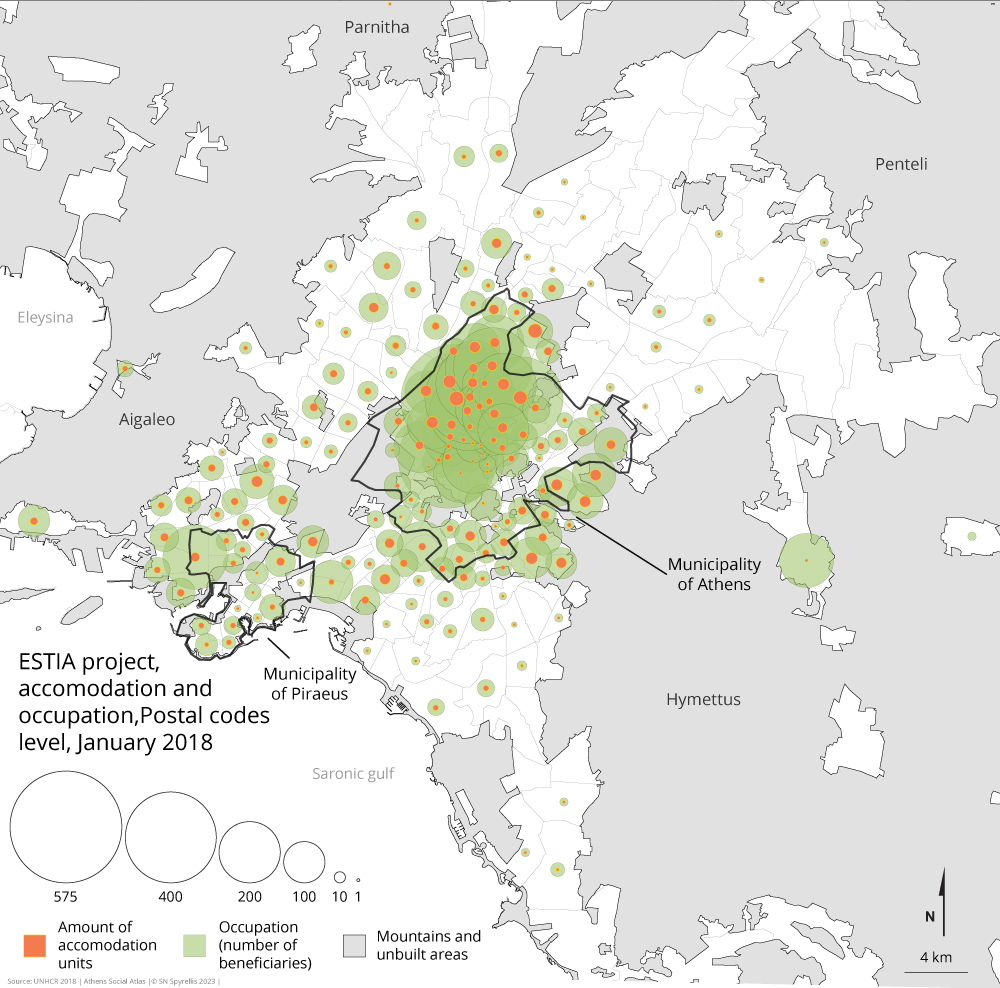

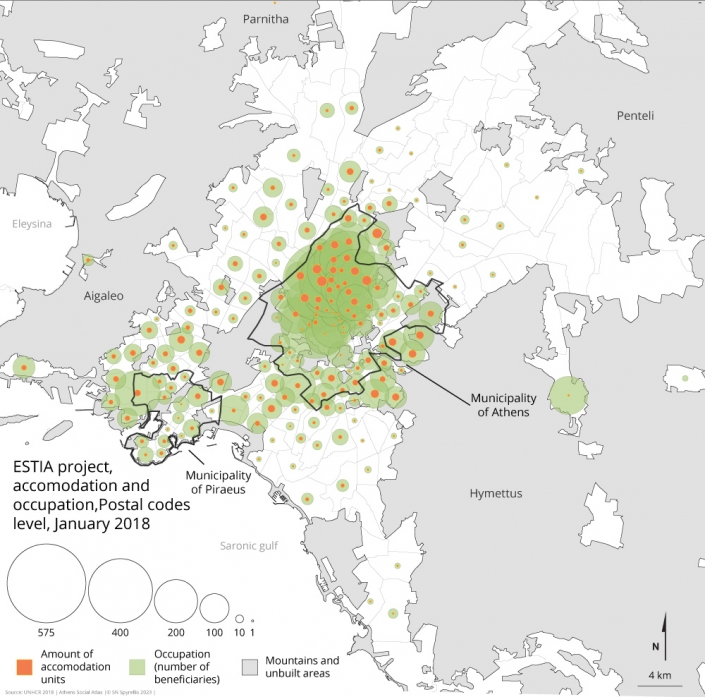

Map 2: Spatial distribution of ESTIA accommodation

Source: UNHCR-ESTIA, 2018

The following spatial analysis showed that the ESTIA temporary accommodation facilities for asylum seekers followed the spatial patterns of migrant settlement in Athens and did not contribute significantly to the increase in the overall segregation of migrants or individual ethnic groups. However, their spatial placement did in the first instance reinforce the spatial concentration of ethnic groups from the Middle East. This condition was most pronounced both around the axis of Patision Street, in the northern districts of the municipality of Athens, and in Piraeus and its neighbouring municipalities (Carte 2). These urban areas are characterised by a strong ethnic segregation that is also found at the level of vertical disadvantaged (micro) segregation (Maloutas et al 2022, Arapoglou & Spyrellis, forthcoming)

Table 2: Urban segregation indicators, population census and accomodation programmes

Source:ΕΚΚΕ-ΕΛΣΤΑΤ, 2015; UNHCR-ESTIA, 2018; UNHCR, 2018

Table 2 shows the values of the dissimilarity, the absolute centralization and the relative centralization indices which have been calculated for different groups of ethnicities adding each time to the census 2011 data the newcomers accommodated in facilities of the ESTIA project and Sites.

The dissimilarity index increases from 0.5113 to 0.5256, i.e., only by 2.8%, when the ESTIA beneficiaries from the Middle East are included in the estimations. Changes in the dissimilarity index are close to zero and negative for all other ethnicities, suggesting that their placement included areas different from the residential locations of their co-ethnics during the census. However, the placement of displaced newcomers strengthened the central concentration of ethnicities from the Middle East; the ACE index rose by 5% (from 0.7675 to 0.8055) and RCE index rose by 27.1% (from 0.3217 to 0.4090) when the ESTIA beneficiaries were included in the estimation. A similar, but weaker change, applies to ethnicities from the Greater Middle East (cf. Afghans) for which the ACE index rose by 1.3% and the RCE index rose by 3.6% when the ESTIA beneficiaries were included in the estimation. Changes in the centralization of migrants from Northern Africa and the Indian Peninsula are negligible.

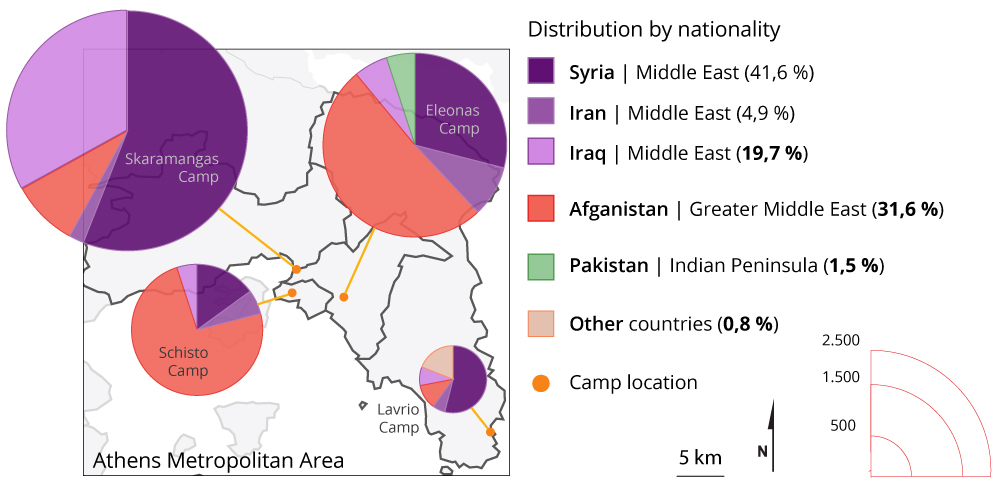

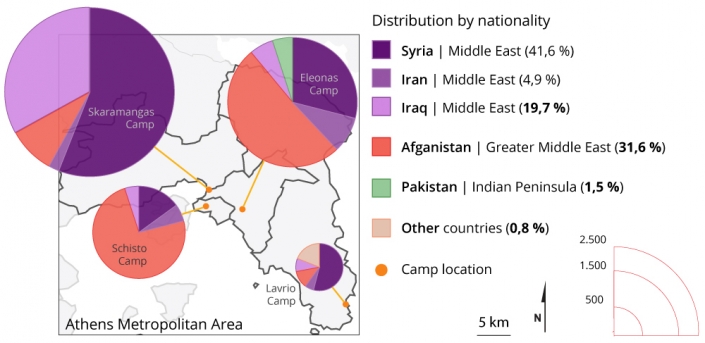

A different effect of the location of Sites in Eleonas, Schisto, Skaramangas and Lavrio on segregation is evident, as has been expected (Map 3). The dissimilarity index increases by an extra 4.8% (i.e., from 0.5256 to 0.5500) when persons from the Middle East contained in Sites are included in the estimations. The increase in the values of the dissimilarity index for ethnicities from the Middle East due to their containment in Sites is more than twice the increase reported for ESTIA beneficiaries. The dissimilarity index also increases by an extra 2.7%, (i.e., from 0.5075 tο 0.5211) when persons from the Greater Middle East contained in Sites are included in the estimations. The increase in the values of the dissimilarity index for ethnicities from the Greater Middle East due to their containment in Sites is almost five times the increase reported for ESTIA beneficiaries.

Changes in the dissimilarity index are close to zero and negative for all other ethnicities. The values of the centralization indices reflect the peripheral location of the majority of Sites (see Map 3) Table 4 shows a significant decrease in the values of the absolute and the relative centralisation index concerning, firstly, ethnicities from the Middle East (cf Syrians) who were transferred from the country borderlands to the most distant locations and, secondly, ethnicities for the Greater Middle East (cf Afghanis).

Map 3: Spatial positioning and ethnic composition of Temporary Reception Facilities in Attica in January 2018

Source: UNHCR, 2018

Fragmentation, infrastructure inadequaces and abeyance management

From the focus group with the different actors involved in the management of the reception infrastructure, a critical assessment of ESTIA emerges, emphasising the fact that actually it was not an integration programme, although it opens channels for integration and contributes to the creation of networks that could support it. The reduction in the potential for inclusion started with the funding itself, since it did not allow for integration actions. There was also a lack of centralised programme design and corresponding financial resources. Consequently, the programmes were adapted to the limited financial opportunities at European and national level. Funding possibilities depended on the type of actors. International organisations had greater access to funding, while public bodies encountered various obstacles.

The specific actions conformed to a managerial spirit, as can be seen from the way in which Structures were opened and their capacity fluctuated, without planning, as a result of political negotiations, both at European, national and local levels (Map 1). The managerial logic was reinforced on the one hand by the residual culture of managing social problems and the explored gaps in the Greek social protection system that was dismantled by austerity policies, and on the other hand, by the deterrent nature of the European Union’s refugee policy (Kourachanis, 2019). A particular issue has been the decentralisation of services without resources to local government and the increasing bureaucratisation of procedures for asylum seekers to access financial assistance and services (Stratigaki, 2022).

In the focus groups with local authorities and NGOs, there was a confusion about the targeting of interventions: the goal of autonomy was presented as more appropriate in the current circumstances, while the goal of integration was presented as difficult. The ambiguity surrounding the broader reception system and the precariousness created by the way specific policies are implemented (when to move from one programme to another, by when they are entitled to what, etc.) place the population targeted in an unresolved situation (Arapoglou and Gounis, 2017; Papatzani et al, 2022). This pendulum situation is a deterrent to an incentive to stay in a place, and more generally a deterrent to those processes that would help people plan their lives.

A very important and structural problem found with ESTIA is that great insecurity arises for beneficiaries at the point of recognition of refugee status. The paradox here is that individuals become more vulnerable from the moment of recognition, since the framework that supports them stops, without having had time to develop mechanisms of self-determination. Another important problem for the integration processes was that the priority in the programme was given to vulnerable cases whose self-determination becomes protracted because they are in great need of support. In addition, the economic recovery and expectations of income from short-term rentals have reduced the available stock of apartments to accommodate asylum seekers and refugees.

Infrastructure creation and expansion: continuities and discontinuities

The operation of shelters within the urban fabric and the clustering around them of, among others, health, education and employment services by NGOs and local government bodies has nevertheless created a legacy of integration strategies that could concern not only migrants but also a wider population in a precarious living situation.

The last source used in this analysis was created between September and December 2020 [3] and maps the network of services linked to the needs of migrants. Through an extensive online survey, 546 services provided by 47 organisations were recorded. Interviews, using a questionnaire, with each agency that was still operating led to verification of the 335 services provided by 23 agencies (Table 3). Training and support (in general) are the most important services and this analysis revealed a significant variation in the internal functioning of the organisations, some providing their services at the stakeholder accommodation while others have a reception area. The latter leads to an increase in the mobility of migrants and vulnerable groups in general in specific neighbourhoods of the city, regardless of their place of residence, further feeding the bottom-up formation of infrastructure and networks.

Table 3: Distribution of registered services by specialisation

Source: Recherche sur Internet et entretiens dans le cadre du programme Inclusive cities

The location of the organisations counted (map 4) confirms that the ESTIA project has created, in central areas, a support network, primarily through the spatial clustering of the implementing organisations. This network can be seen as complementary to the creation of common infrastructures of solidarity organisations from below, although these were often governed by different authorities and after 2019 were systematically destroyed by police actions (Tsavdaroglou & Lalenis, 2022).

Map 4 illustrates the network of services, linked to the functions and needs of the accommodation units, which has been developed in order to meet UNHCR’s priorities for urban accommodation. The establishment of NGOs and humanitarian organisations was crucial to the formation and expansion of this network mainly within beneficiary host neighbourhoods. Smaller charities and solidarity organisations were also established in these areas to provide their services as well. As can be expected, mainly for reasons of proximity to stakeholders, the location of organisations offering their services in specialised individual units (light green spaces) – i.e. having some kind of reception area for stakeholders – largely defines this network. In most cases, in the same central areas, we also find the headquarters of organisations (dark green) that offer their services directly within the accommodation units. The existence of the same model and their choice to locate in these areas, although their location is not related to their best functioning, further highlights the importance of being part of this network. Finally, it is noteworthy, firstly, that this network was mainly based on charities and private actors due to the limited capacities of public actors and lack of funding and, secondly, that social facilities were developed in urban arrival neighbourhoods rather than near camps (where basic services were also provided incidentally by humanitarian organisations within the facilities).

Map 4: Network of services linked to the accommodation programs in Athens

Source: Recherche sur Internet et entretiens dans le cadre du programme Inclusive cities

The creation of reception classes also seems to have strengthened local rallying and solidarity actions. The school community often took on a role of supporting the whole family (parents receiving solidarity from other parents on various issues) as well as a role of inclusion within a community. For this reason, many beneficiaries of the programme chose to remain in the area they were in after leaving the programme.

Another element that emerged from the focus groups with stakeholders is that the inclusionary dimension of ESTIA was also linked to the local political economy especially in the conditions of the economic crisis (renting of vacant houses and buildings, employment of young people, etc.). The long-term nature of such programmes creates various ferment at the level of society and institutions with issues of coexistence.

Municipalities have for the first time entered the process of providing housing services to asylum seekers. In this way they gained a lot of experience and created a network of synergies and cooperation with other services, other institutions and other municipalities. Particularly in the Municipality of Athens, special coordination units were created and innovative collaborations with international actors on both reception and integration issues were developed (Stratigaki, 2022). Moreover, on the occasion of the management of the refugee issue by various institutions and actors, a knowledge around housing policies of different levels was developed which potentially applies to other populations in need.

The findings presented point out that the creation of the accommodation structures and their connection with social infrastructures in the urban fabric contributed to the production of knowledge about the process of inclusion which, however, took place in a community of actors outside the core of the central state, which was unable to exploit it.

Independent living programmes such as ESTIA and HELIOS have been an opportunity to create a culture and a legacy that can be helpful in the wider debate on integration in the city. A debate that forces us to think materially and symbolically about movement and settlement, autonomy and solidarity. But this discussion was rudely interrupted by the termination of the above programmes, the tourism upgrading strategies without inclusiveness provisions, the camp-like arrangement of Reception and Identification Centres, the camps in the hinterland, and the recently established Closed Controlled Structures (Parsanoglou, 2022). In a way, the inactivation of the memory of solidarity and the cancellation of the lessons of integration from the aforementioned programmes contributes to the ‘normalisation’ of camping (Kreichauf 2018) promoted by policies from 2019 onwards. It also exacerbates the risks of polarisation in areas of vertical segregation with the potential operation of dual markets, on the one hand high yields for tourist rentals and gentrified housing and on the other informal rentals of poor quality stock for marginalised groups (Arapoglou & Spyrellis forthcoming).

[1] ΕΛΚΕ Πανεπιστημίου Κρήτης: Project code 10735. Title: ‘Inclusive cities- infrastructures of social integration and refugee settlement’. The project is part of the Centre for Research and Studies in the Humanities, Social and Educational Sciences of the University of Crete.

[2] We would like to thank the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Greece for making the data (snapshots) of the ESTIA project available to the University of Crete.

[3] The online research, interviews and data verification took place in the context of Stavros Aronis internship at the National Centre for Social Research.

Entry citation

Arapoglou, V., Mantanika, R., Spyrellis, S., Κourachanis, N. (2024) Infrastructures of social integration and refugee settlement in Athens, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/infrastructures-of-social-integration-and-refugee-settlement-in-athens/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.119

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Amin, A. (2014). Lively infrastructure. Theory, Culture & Society, 31(7-8), 137-161

- Arapoglou, V. and Gounis, K. (2017), Contested Landscapes of Poverty and Homelessness in Southern Europe. Reflections from Athens, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Arapoglou, V. and Spyrellis, S.N, (forthcoming), Arrival infrastructures: segregation of displaced migrants and processes of urban change in Athens, Geographies

- EKKE; ΕΣΥΕ. Panorama of Greek Census Data 1991–2011. Internet Application to Access and Map Census Data. 2015. https://panorama.statistics.gr/en/ (accessed 2023-08-19).

- Felder, M., Stavo-Debauge, J., Pattaroni, L., Trossat, M., & Drevon, G. (2020). Between hospitality and inhospitality: the janus-face d’arrival infrastructure’. Urban Planning, 5(3), 55-66.

- Hanhörster, H., & Wessendorf, S. (2020). The role of arrival areas for migrant integration and resource access. Urban Planning, 5(3), 1-10.

- IOM (2022), Supporting the Greek Authorities in Managing the National Reception System for Asylum Seekers and Vulnerable Migrants (SMS) – Factsheets, March 2022 (accessed 2023-09-25)

- Kourachanis, N. (2018a), “Asylum Seekers, Hotspot Approach and Anti-Social Policy Responses in Greece (2015-17)”, Journal of International Migration and Integration, 19(4): pp. 1153-1167.

- Kourachanis, N. (2018b), “From Camps to Social Integration? Social Housing Interventions for Asylum Seekers in Greece”, International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 39(3/4): pp. 221-234.

- Κουραχάνης, Ν. (2019), Πολιτικές Στέγασης Προσφύγων. Προς την Κοινωνική Ενσωμάτωση ή την Προνοιακή Εξάρτηση; Αθήνα: Τόπος.

- Kourachanis, N. (2022a), “Housing as a Base for Welfare in Greece: The Staircase of Transition and Housing First Schemes”, International Journal of Housing Policy, 22(2): pp. 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2022.2089082

- Kourachanis, N. (2022b), “Implementing Refugee Integration Policies in a Transit Country: The HELIOS Project in Greece”, European Journal of Homelessness, 16(1): pp. 273-292.

- Linos, K., Frontiera, P., Carlson, M., Jakli, L., Spyrellis, S.N. (2018), Digital Refuge. Berkeley: Berkeley University. URL https://digitalrefuge.berkeley.edu

- Maloutas, T., Spyrellis, S.N., Karadimitriou N., (2022), Measuring and Mapping Vertical Segregation in Athens, in T., Maloutas and N., Karadimitriou (eds), Vertical Cities. Micro-segregation, Social Mix and Housing Markets, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham UK and Northampton MA, USA, pp. 88-97

- Mantanika, R., & Arapoglou, V. (2022). The making of reception as a system. The governance of migrant mobility and transformations of statecraft in Greece since the early 2000s. In Challenging Mobilities in and to the EU during Times of Crises: The Case of Greece (pp. 201-220). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Meeus, B., Arnaut, K., & Van Heur, B. (2019). Arrival infrastructures. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Papatzani, E., Psalidaki, T., Kandylis, G. and Micha, I. (2022), “Multiple geographies of precarity: Accommodation policies for asylum seekers in metropolitan Athens, Greece”, European Urban and Regional Studies, 29(4): pp. 189-203.

- Parsanoglou, D. (2022), “Crisis upon crisis: Theoretical and political reflections on Greece’s response to the ‘refugee crisis”, in Kousis, M., Chatzidaki, A. and Kafetsios, K. (Ed.), Challenging Mobilities in and to the EU during Times of Crises. The Case of Greece, London: Springer.

- Simone, A. (2004). People as infrastructure: intersecting fragments in Johannesburg. Public culture, 16(3), 407-429.

- Stratigaki, M. (2022). A ‘wicked problem’for the Municipality of Athens. The ‘refugee crisis’ from an insider’s perspective. In Challenging Mobilities in and to the EU during Times of Crises: The Case of Greece (pp. 283-297). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Tsavdaroglou, C., & Lalenis, K. (2020). Housing commons vs. state spatial policies of refugee camps in Athens and Thessaloniki. Urban Planning, 5(3), 163-176.

- UNHCR (2018),Greece-SMS WG-Site Profiles – January – February 2018; 2018. URL: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/62505 (accessed 2023-08-19).