2015 | Dec

The international economic role of Athens will be analysed from three different perspectives: international economic activities, supra-regional infrastructures supporting those activities and the attraction of international capital. For obvious reasons, it is necessary to examine two periods: before and after (or during) the crisis.

In the 10-15 years preceding the crisis , Athens was generally absent from various international rankings of metropolises, except for those that also took non-economic factors into account, usually population size or administrative role. The map below (ESPON 2013, 32) presents an assessment of the cities playing some kind of global role in 2008 and places Athens in the third category. It simply confirms various other classifications, which systematically assigned a limited international scope to Athens, no matter which theoretical and methodological approach was used.

Map 1: Global network of cities 2008

Source: Link

At an economic level, the international role of Athens was consistently weak in terms of the higher tertiary sector, especially in the field of services to companies with a supranational scope (including decision-making mechanisms), high tech industries and foreign direct investment (FDI). These weaknesses led to low international competitiveness and the lack of direct and indirect foreign investment. Other points were the absence of globally active financial corporations and) of research activities of global significance. Given the extremely high relative weight of Athens in the Greek economy (almost 50% of GDP) and considering the absence of other cities [1] with a metropolitan role the weakness of Athens could be linked to the weakness of the Greek economy as a whole in the global division of labour. We should bear in mind that the period we are referring to was marked by increasing emphasis (both in literature as well as in the assessments by international organisations) of the importance of international metropolises as active agents in the international role of countries and regions. The weakness of Athens should be examined further, in light of that approach.

The arguments already mentioned do not mean, of course, that there were no data indicating Athens’ international presence. As regards the economic activities themselves, tourism and foreign trade (especially imports) did have an international outreach. In terms of infrastructure (which is also a precondition for these activities), the Piraeus Port and the El. Venizelos airport met all technical and geographical conditions for an international role. Although utilised to some extent, these capacities did not reach their full potential. In certain periods, the Athens Stock Exchange attracted foreign capital (although speculative and without ever having acquired a permanent and strong international role). These isolated elements certainly reflect some comparative advantages of the city, but their concentration and scale do not imply a strong international role.

The limited international economic role of Athens was the result of a number of weaknesses and shortcomings, which can be divided into two categories. The first category comprises the intrinsic dynamics of the national economy that determines the emergence of cutting-edge international activities, which however “come from within”. Parameters such as macroeconomic balance, economies of scale and economic growth rate play a decisive role in creating endogenous activity of this type and, in the case of Athens as well as Greece, these have remained at a low level. The second category comprises factors affecting the spatial choices of international capital in search of appropriate investment locations. Some of them are: proximity to international markets, the nature and stability of fiscal policy, the receptivity of the local community, the environment and quality of life- which have a negative image in most cases in Athens. The city did have comparative advantages (e.g. cultural heritage, climate) but these could not offset its negative characteristics (urbanisation and environmental problems).

In fact, a number of ambiguous characteristics were also not utilised, because this would require a systematic strategy and effort.An example is Athens’ geographical location: negative due to the distance from the European “centre”, but potentially positive for activities in the south-eastern Mediterranean. The last observation points towards another weakness: the failure to understand the importance of Athens’ international presence and the absence of a relevant strategy. A telling fact is that the subject was not even mentioned in the Athens Master Plan for this period (L. 1515/1985 in force until 2014). The planning of the Olympic Games remained focused on the event itself and not on how to exploitat possible multiplier effects, which would definitely reinforce the city’s international role (Οικονόμου 2010).

In the early 2000s, it was thought that strengthening the international role of Athens, to promote it to a higher quantitative and qualitative scale, was a realistic goal. This impression was based on a number of factors, including the provision of new supralocal, large-scale infrastructure (the “El.Venizelos” airport is a typical example), the steady increase in GDP per capita and the climate created by the 2004 Olympic Games. The Games in particular triggered investments that improved the city’s image to some extent, as did the organisational success of the Games that was unparalleled given the size and the administrative tradition of the country.

However, the events that followed did not fulfil these hopes and the international role of Athens was not distinctly reinforced before the onset of the Greek crisis: critical cutting-edge activities in the tertiary sector generally remained unchanged (the penetration of Greek banks in the Balkans did not prove to be viable, research funding remained stagnant…). The impact of the Olympic Games was less positive than what it could have been, for reasons relating to both their extremely high cost and the absence of a timely post-Olympic strategy, while no new investments were made in supralocal infrastructure. Furthermore, a number of negative developments had occurred in fields such as exports to certain countries and, of course, the increase in public debt. Tellingly, those issues, created a dead-end and held back Greece’s international competitiveness, a fact reflected directly on Athens, given its role in the country: A continuous decline in international competitiveness has been recorded since 1987-1988, with the only temporary exception in 1998-2000, where competitiveness accelerated following the accession to the Eurozone (Τράπεζα της Ελλάδος, 2010, 137-138).

The difficulties increased due to developments in the international environment, which had already started to change quickly and had a negative impact on Athens’ prospects for an international role. Indicatively, one can mention the international financial crisis and the European Union’s continuously deteriorating position in the global economic system, as a result of dynamics developing in other parts of the world, especially in Asia but also in South America, which now caused structural changes at a global scale.

The Greek crisis, from 2008-09 onward, hit a city whose international role was already weak, a city that had not seized any opportunities for a positive international course in the previous years and was noted for multiple internal weaknesses. Due to the above reasons, the consequences of the crisis were extremely pronounced. As regards aggregates, Attica suffered the greatest decline in GDP per capita compared to most other regions, while unemployment (which in general increased dramatically in the country) peaked in Attica. Although these parameters are not directly related to the city’s international role, they do indicate that the lack of a strong international presence -to the extent that it characterises Athens- did not make the city more resistant to the crisis.

As for parameters directly linked to the city’s international role, developments were extremely negative in at least three fields: First, the decline in domestic demand led to a reduction in imports from abroad, mainly realised through the port of Piraeus. Second, the financial system, whose high-end operations in Greece are almost exclusively situated in Athens, faced intense pressure due to both the international and the Greek crisis (flight of capital, deposit withdrawal, shrinking bank credit).. These two problems are directly related to the financial aspects of the Greek crisis. However, yet another international activity in Athens collapsed almost entirely, though this cannot be connected directly to the financial issues: Tourism.

Greek tourism mainly attracts foreign tourists; thus, the impact of the crisis due to the decline in domestic demand was offset by an increase in international flows. This increase has multiple causes, relating to both the conditions in the global tourism market, and to the reduced cost of tourist services in Greece due to internal devaluation. However, regardless of its causes, the increase was so intense that tourism is probably the only sector that grew during the crisis – the only exception being Attica. The significant decline in tourist flows in the past and at the beginning of the present decade -30% or more- should mainly be attributed to non-financial aspects of the crisis, and largely to the political and social upheaval and social and environmental problems in the centre of Athens. Tourism in Attica is mostly city tourism (as opposed to sun-and-sea tourism) and the collapse of the international image of Athens and its centre played a decisive role in holding tourism growth back.

Another important question is how Athens’ international financial role was and still is affected to this day by the policies followed to manage the crisis.

First point: The (incomplete) reforms in the labour and product markets as well as in public administration somewhat improved certain critical parameters for the international role of Athens, though not sufficiently to create strong results. This two-fold development, that implies both an improvement and ongoing shortcomings, is reflected in various indicators of the Greek economy’s competitiveness. Given the importance of Athens, the competitiveness of the Greek economy is directly related to the competitiveness of the city’s economy: an increase has been recorded but, given the low starting point, the final result remains unsatisfactory. To summarise, there was a significant improvement in price-related competitiveness, mainly due to the internal devaluation, with consequent significant side effects on GDP and employment. However, structural competitiveness improved much less and quality-related competitiveness declined. Resource transfers to the sectors of commercial goods and services was limited and slow, while the proportion of total good exports from high tech industries more than halved, from 6.6% in 2009 to 3.3% in 2012 (See Anastasatos-Hardouvelis,2014, 112-115). The limited and contradictory progress is evidenced by Athens’ international rankings in this regard. Thus, the World Bank’s “Ease of Doing business” index (which examines only domestic business) ranked Greece in 72nd place among 189 countries for 2013, and in 109th among 183 countries for 2010 (World Bank 2013). In the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) “global competitiveness index” (GCI), Greece only moved from the 83rd position among 142 countries in 2010 to 81st in 2013. In the new 2014-2020 Regional Development Plan of Attica, Athens comes last among European cities operating as business centres: from 32nd place in 2006 to 34th in 2009 and 36th (last) in 2010 and 2011 (ΠΕΠ Αττικής, 2014, 4).

The inability to attract capital, as indicated by both the stagnation of the Stock Exchange and the chronically low levels of foreign direct investment, is due not only to political uncertainty, but also due to structural causes.

Second point: Problematic choices, such as the reduction of deficits not through cuts in public sector expenses, but through heavy general and real estate taxation, affected the whole of Greece, including Athens. With regard to the city’s the international role, uncertainty due to consecutive changes in the taxing system had an even worse impact. In combination with the high taxation for businesses, this is a key criterion for attracting international capital. This point was of particular importance for the wider area of Athens, since it is the main region of the country potentially claiming such a role.

Third point: Privatisation policies and policies for the utilisation of the State’s property bore extremely limited results during the crisis. The main positive example is probably the award to COSCO of a concession to operate a part of the Piraeus port,shortly before the crisis, in 2008. This award led to significant investments and an important upgrade in the role of Piraeus, which no longer operates exclusively as an national import gateway, but has become an international transit port in the Mediterranean. This investment led to positive results for economic development, the public budget and employment. Thus, Greece rose to the 3rd position in the Mediterranean, from the 11th place a few years ago, while it is expected to be in first place by 2016 (http://www.sigmalive.com/inbusiness/news/greek/119307/pos-i-cosco-ekane-to-thavma-sto-limani-peiraia#.dpuf). Currently, this investment seems to be widely accepted even by some of its most ardent critics. On the other hand, the policy of “fast” investments in public or private property, known as “fast track”, has brought about few practical results.

The problem is not due to lack of investor interest, but because of the inability to quickly complete the necessary procedures and authorisations. After five years of legislative and organisational efforts, approximately 5-6 public and private strategic investments have only reached the approval stage. This means the investment itself has not started yet and there are no essential fiscal or developmental results at the moment. The two most highly priced assets that have been earmarked for potential public property utilisation, Asteras Vouliagmenis and Ellinikon, are probably those presenting the greatest difficulties too. The deal for the first one is subject to cancellation by the Council of State and is plagued by wrong choices of land use, while the current government questions the purpose of the second investment.

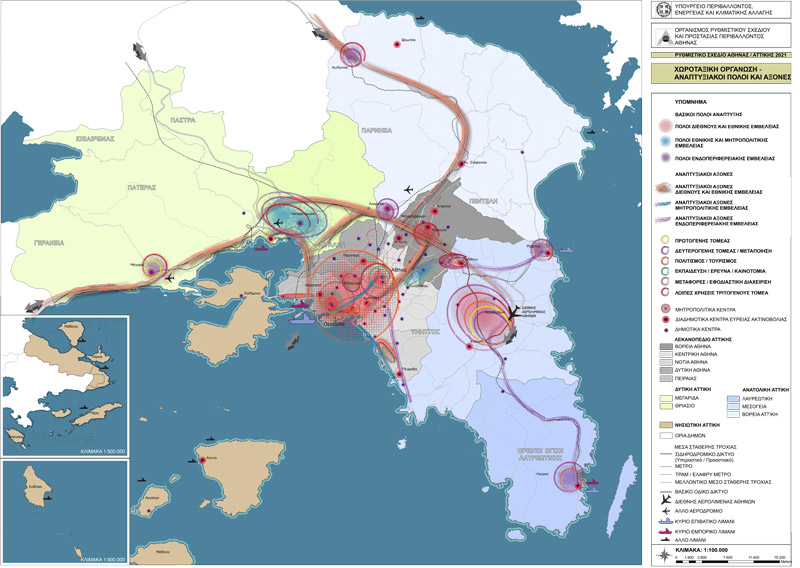

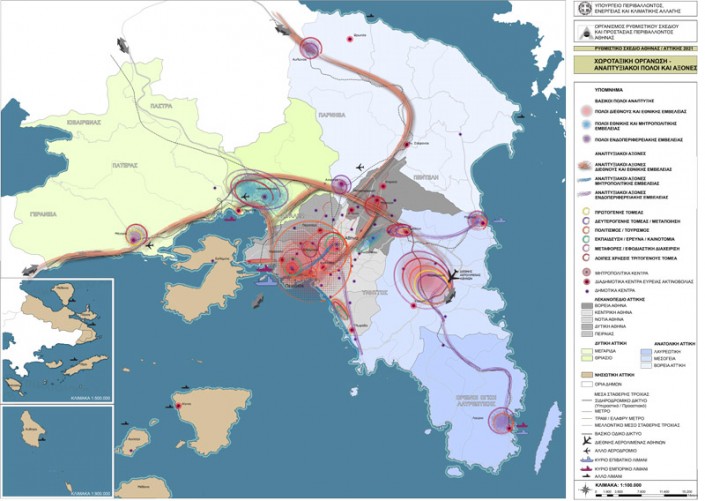

The importance of a metropolis such as Athens has been taken into account at a strategic level, as we can see in the Master Plan of Athens – approved in 2014.The relevant map of the Athens Master Plan Organisation includes points directly connected to the city’s international role. The same applies to the new NSRF 2014-2020 (National Strategic Reference Framework –‘ESPA’). The new NSRF focuses on the international role of Athens-Attica in general, but also specifically on critical parameters such as Research and Technological Development (ΥΠΑΑΝ 2014, 72). The 2014-2020 Regional Development Plan aims at transforming Athens into a “Mediterranean Capital”. However, these programmes only concern the future.

Map 2: Athens Master Plan: Spatial organisation – pillars and axes of development

Source: Link

Map 3: International rankings of cities, 2012

Source: Link

[1] In theory, Thessaloniki could play such a role too although it is marginal in terms of its size. Thessaloniki, however, is similar to Athens in terms of its weaknesses.

Entry citation

Oikonomou, D. (2015) The international economic role of Athens, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/international-role/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.54

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Αναστασάτος Τ και Χαρδούβελης Γ (2014) Η μακροοικονομική ανταγωνιστικότητα της ελληνικής οικονομίας. Στο: Ελληνική Ένωση Τραπεζών, Ανταγωνιστικότητα για ανάπτυξη: Προτάσεις πολιτικής, Αθήνα: Ελληνική Ένωση Τραπεζών, σσ 97–120.

- Οικονόμου Δ (2012) Χωρικές ρυθμίσεις για τη δημιουργία ενός φιλικού επενδυτικού περιβάλλοντος: οι στόχοι και οι αναγκαίες παρεμβάσεις. Στο: Εισήγηση στην επιστημονική εκδήλωση της Επιστημονικής Εταιρείας Δικαίου Πολεοδομίας και Χωροταξίας (ΕΕΔΙΠΟΧ) Επιχειρηματικότητα και Σχεδιασμός του Χώρου, Αθήνα.

- Οικονόμου Δ (2010) Ο Νέος Ρόλος της Ελλάδας στον Ευρωπαϊκό, Μεσογειακό και Βαλκανικό Χώρο. Στο: Ημερίδα Χωρική Ανάπτυξη, Χωρικές Πολιτικές, Αθήνα: ΕΜΠ, σσ 130–136.

- Οικονόμου Δ, Γετίμης Π, Δεμαθάς Ζ, κ.ά. (2001) Ο διεθνής ρόλος της Αθήνας. Οικονόμου Δ, Γετίμης Π, Δεμαθάς Ζ, κ.ά. (επιμ.), Βόλος: Πανεπιστημιακές Εκδόσεις Θεσσαλίας.

- ΠΕΠ Αττικής (2014) Περιφερειακό Επιχειρησιακό Πρόγραμμα Αττικής 2014-2020. Αθήνα.

- Τράπεζα της Ελλάδος (2010) Νομισματική Πολιτική 2009-2010. Αθήνα. Available from: http://www.bankofgreece.gr/BogEkdoseis/NomPol20092010.pdf.

- ΥΠΑΑΝ (2014) Εταιρικό Σύμφωνο για το Πλαίσιο Ανάπτυξης-ΕΣΠΑ 2014-2020. Αθήνα.

- Doing Business (2013) Doing Business 2014. Understanding Regulations for Small and Medium-Size Enterprises. Washington DC. Available from: http://www.doingbusiness.org/~/media/GIAWB/Doing Business/Documents/Annual-Reports/English/DB14-Full-Report.pdf.

- ESPON (2013) New Evidence on Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Territories. Luxembourg. Available from: http://www.espon.eu/main/Menu_Publications/Menu_MapsOfTheMonth/FirstESPONSynthesisReport.html.