The logic and practices of administration levels: Metropolitan governance

Chorianopoulos Ioannis|Pagonis Thanos

Planning, Politics

2015 | Dec

Metropolitan space is essentially the space in which the financial and social impacts of an urban core are recorded. Defining a Functional Urban Region (FUR) has been a concern in most European urban planning frameworks since the post-war period, while the emergence of the “metropolitan periphery” as a separate level of governance indicates the specific significance of this scale in matters of urban space regulation. In the case of Athens, the absence of such provisions from the State administration until recently, reflects the political dominance of views that approached unplanned urban growth as the fastest track to economic growth.

The political demands for the creation of metropolitan structures in spatial planning became more specific in Athens in the mid-1980s (1985 Master Plan), as a result of failures and environmental dead-ends the city was facing. However they were not complemented with any administrative restructuring. At the same time, a number of new intergovernmental challenges arose, that were mainly related to the management of EU development programmes. The next two decades saw an intense effort to implement administrative reforms. Indicatively, the Region of Attica was created(1986); five municipal administrations (Athens, Piraeus, the Joint Prefecture of Athens-Piraeus, East Attica, West Attica) were upgraded to political authorities (1994), and municipalities and communities were consolidated as part of the “Kapodistrias” programme (1997). In spite of those efforts, reform often stumbled on institutional barriers which led to setbacks. The thorny issue of transferring spatial planning responsibilities from central administration to local authorities proved to be a key problem about which the Council of State generated a wealth of case law (Βασενχόβεν κ.ά. 2010). Thus, ultimately, the decision to establish a democratically accountable governance body responsible for the entire metropolis was never taken. As a consequence, development in the Athens region remained under the responsibility of central government.

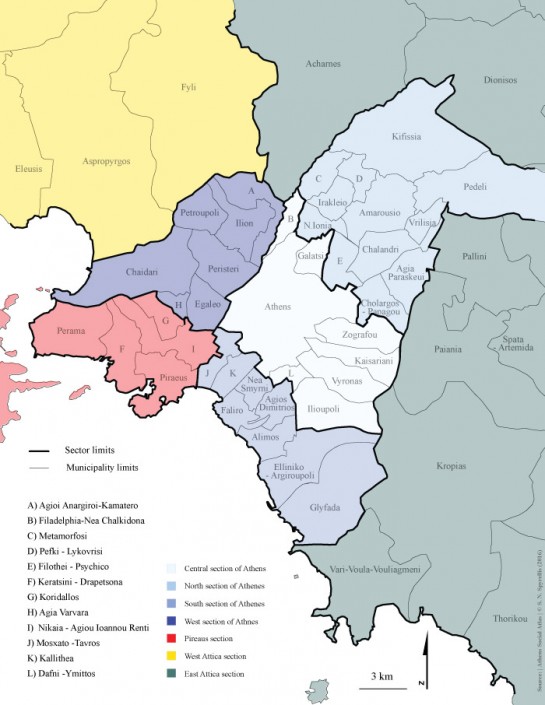

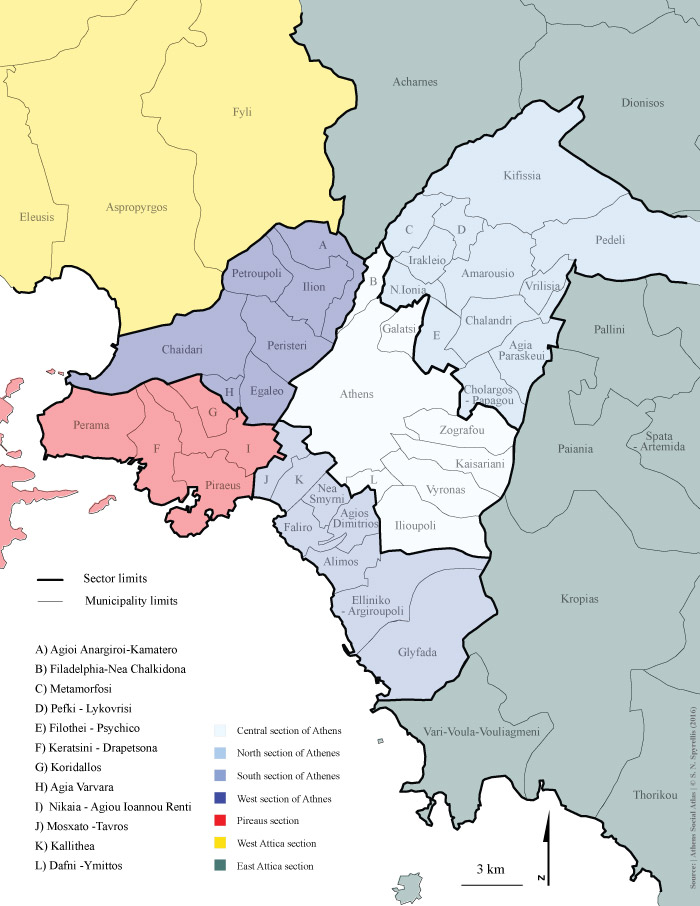

Map 1: Regional units of Attica

Map 1: Regional units of Attica

During the preparation for the Olympics, the lack of appropriate decentralised governance structures meant that the metropolitan planning of Athens was carried out by the central government administration. Although the Olympic interventions were pivotal to the city’s future development, the entire project was seen as a special occurrence and thus was managed through a special legal and organisational framework. In this way, the Athens Plan, which posed obstacles to the planning of the Olympics, was circumvented (Chorianopoulos et al. 2010). The opportunity to restructure metropolitan governance on a more rational basis was lost. In parallel, the transfer of key responsibilities for metropolitan planning to various ad hoc bodies and organisations resulted in a serious democratic deficit. This condition was carried forward to the post-Olympic era by extending ad infinitum the special exemption clauses applying to the Olympic project areas. In the years that followed, this fragmented governance approach was not effective in tackling issues of metropolitan significance. To some extent, governance ineffectiveness negated some of the benefits of the Athens Olympics.

The recent effort to re-organise territorial governance structures through the ‘Kallikrates’ programme (2010), was an effort to address those issues. A new, elected, governance body was established: the Metropolitan Regional Authority. Its remit covered the metropolitan region and several responsibilities of metropolitan significance were passed on to it . In parallel, the region’s 122 municipalities and communities were merged into 66 municipal authorities. The new governance architecture of the metropolis and the allocation of responsibilities between various administrative levels are outlined in figure 1.

Figure 1: Administrative levels

The ‘Kallikrates’ programme was based on other examples of territorial governance reforms, implemented in other EU countries over the previous two decades. Their aim was to improve the cost-effectiveness ratio in the provision of services and to create new institutional structures that could support the European growth orientation and the competitiveness of local economies. The process of refocusing local objectives was legitimised by increasing the presence of local institutions and lobbyists in special participatory decision-making platforms, the so-called “Consultation Committees”. This made local societies responsible for the consequences of their choices (Chorianopoulos 2012).

These priorities are apparent in the new intergovernmental structures of Athens. A significant change, among others, was the representation of Athens in the European Committee of the Regions from the newly founded Metropolitan Regional Authority. In addition, the enlarged local government units could now participate in European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation, i.e. in development-related ‘consortia’ with institutions from other EU member states which aim at promoting their common economic interests.

However, the ‘Kallikrates’ reform was not free from path dependencies linked to the recent, centralised past. These dependencies created doubts as to the ability of the new institutions to meet expectations. New municipal units, for example, were unified according to administrative proximity between neighbouring local authorities and did not take into account the operational limits of each territory. The main responsibilities for spatial planning, like the approval of Comprehensive Urban Plans (Genika Poleodomika Schedia) as well as the implementation of the Regulatory Plan (Rythmistika Schedia) and the Urbanisation Control Zones (ZOE), remain under the jurisdiction of the central government.

The financial crisis and the special administrative framework produced by the country’s bailout-agreement obligations are important factors determining the operational framework and practices of new institutions. These special conditions led to changes in policy priorities. The logic of growth irrespective of cost came to the fore once more. This change of priorities was coupled by suitable arrangements in administrative structures, which revoked the fractional approaches of the previous period. A characteristic example is the way in which central government promotes strategic investments in Attica by awarding special status to specific locations such as the Ellinikon or the Saronikos coastal front. At the same time, it is important to mention the increasing role of private foundations in urban interventions and projects of metropolitan significance. These foundations have become significant partners of central government, in support of new policy goals. Figure 2 summarises those changes and underlines the excessive presence of institutions controlled by central government in the spatial governance structure of the metropolis. A key territory where policies focus is the centre of Athens, where the issue of effective cooperation between central government, metropolitan administration and local administration is still to be resolved.

Figure 2: Mapping of evolution of central government responsibilities in metropolitan planning of Athens

Entry citation

Chorianopoulos, I., Pagonis, T. (2015) The logic and practices of administration levels: Metropolitan governance, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/metropolitan-governance/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.46

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Βασενχόβεν Λ, Ασπρογέρακας Ε, Γιαννίρης Η, κ.ά. (2010) Χωρική διακυβέρνηση: Θεωρία, Eυρωπαϊκή εμπειρία και η περίπτωση της Ελλάδας. Βασενχόβεν Λ, Ασπρογέρακας Ε, Γιαννίρης Η, κ.ά. (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Κριτική.

- Chorianopoulos I (2012) State spatial restructuring in Greece: forced rescaling, unresponsive localities. European Urban and Regional Studies, Sage Publications 19(4): 331–348.

- Chorianopoulos I, Pagonis T, Koukoulas S, et al. (2010) Planning, competitiveness and sprawl in the Mediterranean city: The case of Athens. Cities, Elsevier 27(4): 249–259.