Adjustments to the financial crisis: redistributing vulnerability and producing new long-term risks

Chalkias Christos|Delladetsimas Pavlos – Marinos|Sapountzaki Kalliopi

Politics, Social Structure

2015 | Dec

Government adjustments to the crisis and their social impact

The sovereign debt crisis and the long-term recession in the country have brought about social, economic, demographic and environmental changes that increase human and social vulnerability to physical, environmental and other new or long-forgotten social risks (such as energy poverty, malnutrition, homelessness). In addition, human and social vulnerability are attenuated by the reduced capacity of welfare institutions to respond to crises and the acute needs that arise from them (Sapountzaki and Chalkias 2014).

How did these developments occur? Since the beginning of the financial crisis in 2010, the attitude of Greek governments against it assumed the form of a failure to meet state financial obligations in the context of a purely fiscal and macroeconomic approach. Adjustment was achieved through cuts in wages and pensions, increased direct and indirect taxation, lay-offs, downsizing of welfare provision and other policies of budgetary consolidation. These are policies and austerity measures -as mentioned before- that triggered new social risks (or revived older ones). A large part of Greek society , in particular sensitive social strata whose population swelled compared to the pre-crisis period, were directly exposed to them. Many households in Athens were struck by the sudden and unexpected exposure to the risks of unemployment, poverty, energy poverty, malnutrition, psychological depression, morbidity, premature death, eviction, forced migration. In other words, governmental and macro-economic vulnerability was transformed to human and social vulnerability, and was passed on to social strata directly dependent on the welfare state.

Of the chronic risks that reappeared with the crisis, the most serious were related to health. The relevant literature already provides strong evidence regarding the relationship between income levels and health indicators, such as morbidity, mortality, life expectancy and access to health care (Photo 1). Unemployment, part-time work, job insecurity and home loss are forcing large numbers of people to social exclusion and cause mental disorders. Unemployed individuals and members of their households are exposed to greater risks of premature death, chronic diseases and disability. In the long-run, unemployment increases the risk of suicide and is also associated with increasing alcohol consumption, with obvious long-term health consequences (Μαλλιαρού και Σαράφης 2012). In their article in The Lancet, Economou et al. (2011) confirm the increase of suicides and of infectious diseases in Athens (Photo 2).

Photo 1: Pensioners losing access to services and healthcare goods

Photo 2: Austerity kills

Increased institutional vulnerability in the healthcare system (again due to the crisis) further enhances health risks. In conditions of economic recession, shelters for those in need suffer underfunding problems due to cuts in public expenditure. Budget deficits and high unemployment cause insurance funds to cut back on expenses and also lead to liquidity problems in private hospitals and health centres. While the demand for medical services, particularly public ones, increases (due to loss of income and the increase of diseases) the healthcare system itself suffers from progressively increased vulnerability (Μαλλιαρού και Σαράφης, 2012).

Adjustments of households and social groups: Who suffers from vulnerability or is exposed to new threats?

For their part, vulnerable groups, local institutions and social organisations often react with innovative adjustments in order to manage risks in everyday life and the increased vulnerability they entail (Sapountzaki 2012). Examples of personal and social adaptability that are beneficial to the current and future public interest include: the shift of Athenians to public transport in order to avoid fuel costs, the reduction of household waste, energy savings within the house to reduce electricity bills (Graph 1), the creation of social structures to combat poverty and inflation (for example, movements to avoid intermediaries; social grocery stores, clinics and pharmacies; municipal vegetable gardens (Photo 3); food distribution centres for people in need (Photo 4) etc.) These structures succeeded in passing vulnerability on to groups less affected by it. For example, while offering free staple goods to those who need them, social groceries also attract part of hypermarket consumers by selling to the general public at equal or lower prices.

Graph 1: Electricity consumption in the Municipality of Attica (1993 – 2011)

Photo 3: Poster of a municipal vegetable garden

Photo 4: Food distribution centre of the City of Athens

There are many examples of personal and social adaptability, which may prove harmful in the long run for other social strata, the environment and the public interest. Indicative cases are: the use of wood for heating; resorting to cheap but unsuitable accommodation; switching to cheap fast food and to foodstuff of ambiguous quality and safety; cutting maintenance costs in manufacturing, transport, construction etc.; the rolling back of the regulatory framework for spatial development and environmental protection in order to attract investment etc. These practices have already led -or will lead in the future- to new threats or forms of exposure to recurring risk: atmospheric pollution (Photo 5); technological accidents; urban fires; health risks and morbidity. The adjustment of individuals and groups may even increase institutional vulnerability. A typical example is the reduction in the population of volunteer fire-fighters since many abandon voluntary work in order to find a second part-time job.

Photo 5: Smog in Athens due to wood and other waste used for heating, January 2014

Those successfully adjusting to the risks of the crisis are people with access to resources (not only financial), who can develop the factors which enhance adaptability (flexibility, redundancy, feedback, efficiency, innovation, networking, self-organization, learning ability, experience-knowledge-memory, cross-reactivity to different scales of space and time).

For example:

- Individuals and households moving to cheaper rental accommodation, changing the structure of their households, the repayment period of mortgages, their diet, their mobility and consumption patterns.

- Social groups and communities building social economies of needs (spare part networks, markets bypassing intermediaries etc.) and other solidarity structures to boycott high prices of goods in the open market.

- The sectors of wholesale, retail and processing are turning to cheaper raw materials and promote lower-quality goods and services.

- Local authorities cooperating with NGOs to create structures to combat unemployment, poverty and homelessness in an effort to restore their shaken confidence and regain their political prestige.

However, some of these adjustments, be it conscious or spontaneous reactions to the crisis, contain latent risk exposure. In this sense, they cause new threats to emerge and unfairly transfer additional vulnerability to already vulnerable groups. The results of this self-regulating vulnerability adjustment by multiple social agents and at various spatial scales, during the crisis in Athens, are still unpredictable. According to the Government’s rhetoric, the main priority is still the sustainability of public finances and the macroeconomic soundness of the country within the Eurozone. However, the adjustments of society at a social, economic and political level will indicate whether these priorities are adopted by Greek society as well.

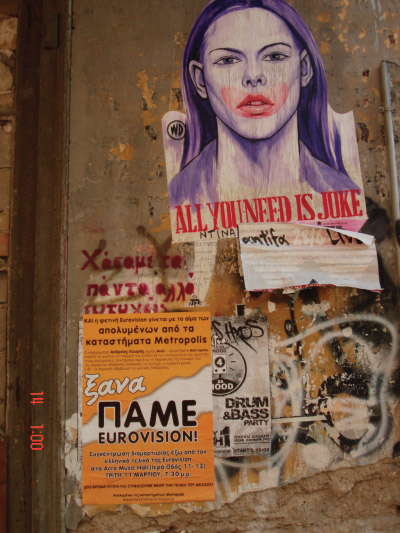

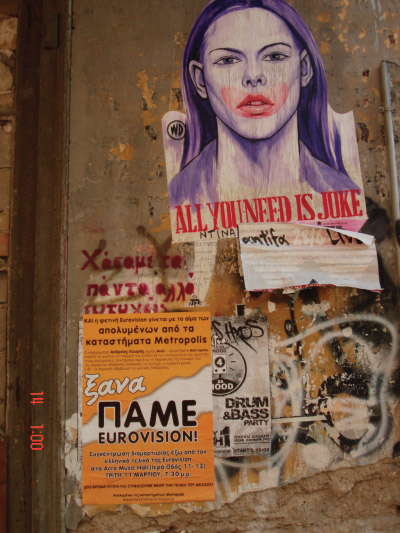

Photo 6: Poster against the adjustment of a group of companies and other“ harmless” forms of adjustment

Entry citation

Chalkias, C., Delladetsimas, P. M., Sapountzaki, K. (2015) Adjustments to the financial crisis: redistributing vulnerability and producing new long-term risks, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/natural-and-social-vulnerability/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.39

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Μαλλιαρού Μ και Σαράφης Π (2012) Οικονομική Κρίση. Τρόπος Επίδρασης στην Υγεία των Πολιτών και στα Συστήματα Υγείας. Το Βήμα του Ασκληπιού. Ηλεκτρονικό Περιοδικό του Τμήματος Νοσηλευτικής Α΄ 11(1): 202–212. Available from: http://www.vima-asklipiou.gr/volumes/2012/VOLUME 02_12/VA_REV_5_11_02_12.pdf.

- Economou M, Madianos M, Theleritis C, et al. (2011) Increased suicidality amid economic crisis in Greece. The Lancet 378(9801): 1459–1460.

- Sapountzaki K (2012) Vulnerability management by means of resilience. Natural Hazards, Springer 60(3): 1267–1285.

- Sapountzaki K and Chalkias C (2014) Urban geographies of vulnerability and resilience in the economic crisis era–the case of Athens. AZ Journal, special issue ‘Cities at risk’ 11(1): 59–75. Available from: http://www.journalagent.com/itujfa/pdfs/ITUJFA-19480-DOSSIER_ARTICLES-SAPOUNTZAKI.pdf.