2015 | Dec

The 2004 Olympic Games lent a new, international image and role to Athens, albeit for a limited period of time. Under extraordinary pressure for the timely completion of projects and the organisation and management of the Games, special bodies were established to manage large-scale, urgent needs, smoothly and effectively. In addition, the 2004 Olympics triggered the extraordinary transfer of public investment resources from various economic, social and geographical priorities to new ones, that moved from the periphery to metropolitan Athens. According to General Accounting Office data, the total cost directly related to the Games reached 8.486 bn euro. Some of the main arguments affecting public opinion in favour of the event were that “Athens would finally be placed on the international map” or that this would be “an opportunity to move things forward a little” within an inert and problematic metropolitan context. Due to those attitudes, rational views, which sought ways for the capital to reap the benefits of the Games in the the post-Olympic period, were discounted. There were proposals to create a new metropolitan authority and to formulate a strategic plan for the future. Although, these proposals were not implemented, Athens did see an unprecedented number of major investment projects and initiatives that directly or indirectly influenced its growth dynamics.

The planning of the Games was supported by two main authorities, established for this purpose, which operated in parallel and autonomously from the existing government institutions on all administrative levels. Law 2598/24.3.1998 established two major ad hoc authorities: The National Committee for the Olympic Games and the Organising Committee of the Olympic Games (‘Athens 2004 SA’). Within this context, an emergency Law for the Olympic Works was passed in 1999 (Law 2730/25-6-1999). It introduced specific urban planning provisions for regions and municipalities hosting Olympic works, new procedures for private and public land and property acquisition, as well as new organisational and administrative arrangements. Undoubtedly, this institutional intervention suggested a significant rupture with regular political practices and planning processes.

That law underlined the primacy of the Olympic Games objectives over established methods of serving the public interest. That alone was enough to introduce ad hoc modifications into the Athens Master Plan and to empower the (then) Environment Minister to establish a common planning permission process for all municipalities hosting Olympic Works and Facilities across the country. The primary intention in this case was to centralise the necessary procedures in order to achieve a uniform and comprehensive permit system. This would facilitate the roll-out of stringent safety standards and would ensure the coordination of all necessary actions across all government levels within a tight schedule.

As a result, each local region hosting Olympic Works, the Ministry of Environment Planning and Public Works and the Ministry of Culture, in cooperation with the Organisation for Planning and Environmental Protection of Athens (ORSA) and local administrations, prepared a Unified Special Plan, which was then ratified by Presidential Decree. The Special Plan included all the necessary planning, construction and environmental regulations for the development of the Olympic Works. It was drawn up in order to accelerate decision-making and the implementation of plans or other related measures. Even more indicative of the urgent nature of the Olympic Laws were the new land expropriation code provisions . Due to the delays that occurred when the standard procedures were followed, the government voted in a new law to further simplify the Expropriation Code and relevant procedures (Law 228/9-10-2001). Other special arrangements related to the temporary use of real estate and facilities, the transfer of venues and the use of coastal areas.

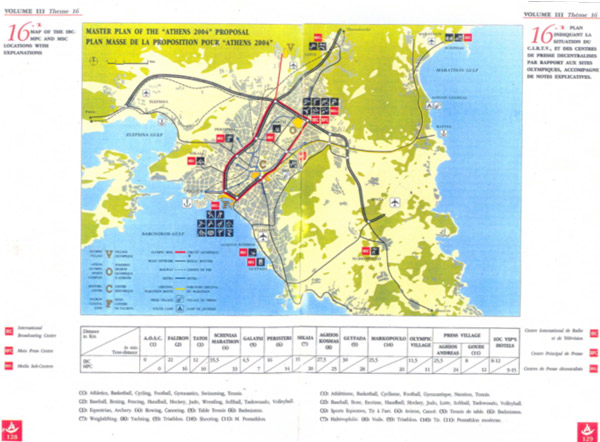

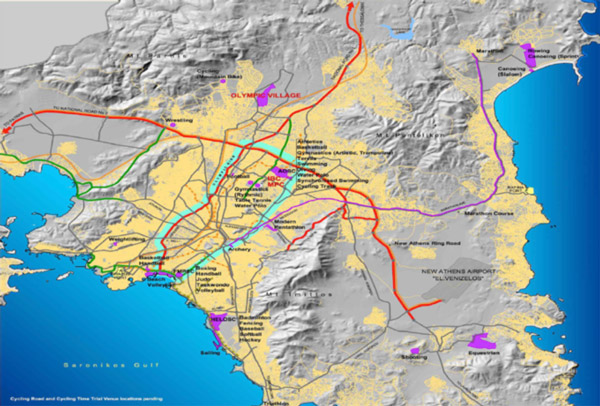

The basic strategic principles of the Olympic Games (OG) – based on two successive plans prepared for the candidacy – remained more or less unchanged. The final plan reproduced those principles (maps 1, 2) though not without modifications. The integration of the Olympic projects in a broader strategy for the metropolis, was exclusively based on transport and technical infrastructure. The main expected benefits related to the provision of technical and transport infrastructure in the Attica basin (Committee for the Athens 2000 Candidacy, 1996; Committee for the Athens 2004 Candidacy, 1997). A special research report that was carried out in preparation for the application file of the 2004 OG (Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλίας ΟΡΣΑ 1998) brought up the issue of a common strategy for the metropolis in conjunction with the OG, for the first time. The research focused on macro-economic, developmental dimensions (tourism, public resources, consumption patterns, employment, public works and infrastructure) and the impact of the OG on the country as a whole. As a result, ensuing policy followed primarily a technical-business approach, which was not combined with the socio-economic priorities of the city and the post-Olympic development prospects.

Map 1: The initial proposal for the spatial Organisation of the Olympic Games

Source: Athens 2004 bid file

Map 2: Final Proposal for the spatial Organisation of the Olympic Games

Source: Athens 2004 bid file

The spatial strategy aimed at creating four Olympic hubs, combined with a central axis, which would span the Attica Basin from Mt. Parnitha to the Coastal Zone of Faliron. The four poles were:

Hub 1: The Olympic Village (Municipality of Acharnes) (map 2)

Hub 2: The Olympic Sports Complex (OAKA) (Municipality of Maroussi) (photograph 1)

Hub 3: The historic centre of Athens (Municipality of Athens)

Hub 4: The Coastal Zone of Faliron (Municipality of Paleo Faliro, Kallithea, Moschato, Piraeus)

The hubs were interlinked with an Olympic Ring, integrated with the country’s regional and national transport network (Οργανωτική Επιτροπή Ολυμπιακών Αγώνων «Αθήνα 2004» 1999). The Olympic Ring provided access to all sports facilities, within 20 minutes on average (Map 2). The final decision on project planning and construction permissions was the responsibility of a special Committee of Ministers to which the Deputy Minister of the Environment, Planning and Public Works introduced proposals for discussion.

The development of the venues was not limited to the four hubs. It also included: The Olympic Centre (Ano Liosia), the Weightlifting Centre (Nikaia), the Boxing Centre (Peristeri), the Sports Facilities at the former airport of Ellinikon, the Olympic Equestrian Centre and Shooting Centre (Markopoulo), the Rowing Centre (Schinias-Marathon) etc. Moreover, during the Games, 10.000 media representatives were housed in seven purpose built “Media Villages” (ASPETE, Ilida-Maroussi, OTE-Pallini, Agios Andreas, Amygdaleza, NTUA, University of Athens).

Map 3: The final Olympic Village land use plan

Source: OEK (Workers’ Housing Organisation) 2001

The Olympics effort included another parameter: improving the city’s image and public space. For this purpose, a Strategic Plan concerning additional OG works was drafted (ORSA 2000-2003). It outlined a programme to revive the city and included a series of initiatives such as:

- Infrastructure Projects

- Remediation and Upgrade of the Coastal Front of Athens.

- Improvement of the City’s gateways .

- Unification of the Archaeological Sites

- Improvement of the Historic Centre and adjacent Areas

- Neighbourhood improvements in Piraeus

- Revival of Areas around the Olympic Sites and their Access Roads

- Actions for improving the image of the City of Athens.

These projects were awarded to foreign and Greek architects (for example, the roof of the Olympic Stadium and the pedestrian bridge over Mesogeion Avenue were assigned to S. Calatrava) in an attempt to enhancethe international image of the city.

Photograph 1: Hub 2 – The Olympic Sports Complex (OAKA) (Municipality of Maroussi)

Map 4: An outline of the sports facilities at the former Airport of Ellinikon

Source: “Athens 2004”, 2003

Finally, special mention should be made to large infrastructure investments – mainly in transport – that were connected to and/or brought forward due to the Olympic Games. Attica received an unprecedented wave of investments in infrastructure, which radically changed the accessibility and the geography of many urban quarters. These investments were: the Athens International Airport, the extension of the Metro lines, the Suburban Railway, Attiki Odos, the ring road of Imittos, the Tram, the improvement of infrastructure of the port of Piraeus and a vast number of smaller improvements to roads and connections.

The main tools for the implementation of works and the promotion of development initiatives were the “Special Plans” (mentioned above) and the “Cooperation Agreements” between Athens 2004 and the institutions and organisations involved in the Games. In other words, “Athens 2004” would sign a series of programme contracts, cooperation memoranda and business contracts with Ministries, local governments and other organisations. The contracts gradually expanded to include business associations and chambers. Financial difficulties, time constraints and organisational pressures prevented the implementation of many of these contracts. Some remained inactive, the scope of others was limited and others were cancelled. The bulk of the contracts that were never activated had to do with agreements covering the post-Olympic period.

The impact of the OG on the urban fabric 12 years on, has not yet been studied systematically. Ideally, the impacts should be linked to the development phases of the OG. These phases were divided in: a) preliminary and/or preparatory, b) construction and organisation c) the Games period (13-19 August 2004) and d) the post-Olympic phase. Significant benefits were recorded in the The period, however, that effectively lacked coherent strategic interventions (both throughout Attica as well as in other Greek regions) was the post-Olympic period. The key post-Olympic legacy of the Games was the construction of major new infrastructure and the subsequent effects this had on accessibility. However, one problem remained unsolved: the way that infrastructure was locally integrated and how they affected the urban dynamic. We also know very little about how that infrastructure affected local communities, local economies and population mobility.

The most negative aspect of this entire effort is the management of the Olympic buildings, facilities and infrastructure in the post-Olympic period (ΥΠΠΟ – ΓΓΟΑ, 2003). The city was faced with an oversupply of venues (mainly for sport uses) but had no strategy for their utilisation by users, tenants and/or buyers (Delladetsimas 2003). As already mentioned, the spatial policy and development of the Olympic projects was not combined with the general economic conditions of the city and, even more, with local dynamics and needs. Major key projects concerned privileged areas of the Attica basin (e.g. Municipality of Maroussi). Instead, “degraded” Municipalities hosted only isolated buildings and facilities (Nikaia, Ilion). The only exception might be the Olympic Village, which is currently a source of problems for the already burdened Municipality of Acharnes. The Olympic programme did not focus on developing common post-Olympic objectives and complementary actions through local development strategies. This means there was no systematic approach towards developing common objectives with local communities concerning the Olympic venues, the potential post-Olympic utilisation and the development of joint funding schemes. The Olympic works, in general, were a purely technical-construction activity that was not incorporated into an urban strategy, nor associated with planned private sector proposals.

As a result, the entire operation ended up in post-Olympic inertia, while facilities and buildings were transferred to public bodies and sports federations or leased to private companies under long-term contracts via ad hoc decisions. However, the majority of the building stock still remains deserted, burdened with increased maintenance costs. The most characteristic cases are the under-utilised Olympic Sports Complex and the (former) international zone of the Olympic Village. There is a pending tender for the international zone’s unbuilt areas, while the buildings remain abandoned. In addition, parts of two key Olympic zones, the Faliron Delta and Ellinikon have been leased to the “Stavros Niarchos” Foundation and Lamda Development to be developed for uses different to those formulated in the plans for the Olympics. The management of Olympic real estate and facilities is partly the responsibility of the Public Property Company (ETAS SA) -which was created by merging “Public Real Estate Company SA”, “Greek Tourist Properties SA” and “Olympic Properties SA” – and partly the responsibility of the Hellenic Republic Asset Development Fund (HRADF SA). ETAS manages the following Olympic properties: Faliron Olympic Complex, Schinias Rowing Centre, Ano Liossia Olympic Centre, Panthessalian Stadium, Olympic Equestrian Centre of Markopoulo, Goudi Olympic Complex, Markopoulo Olympic Shooting Centre, Nikaia Olympic Center, International Broadcasting Center (IBC), Main Press Centre, Galatsi Olympic Centre, the Panpeloponnesian Stadium (allocated to the municipality) and the Cretan Stadium (gifted to the municipality).

The Olympic Complex of Goudi-Badminton, has been leased to a private company. The former International Broadcasting Centre (IBC) in Maroussi was leased to a private company (Lamda Development) and has become a shopping mall (Golden Hall). As for the Tae Kwon Do building, which temporarily served as an event venue, an international public tender is currently under way for turning it into an International Conference Centre through private investment.

Entry citation

Delladetsimas, P. M. (2015) Olympic Games and Olympic Venues, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/olympic-games-2004/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.57

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Οργανωτική Επιτροπή Ολυμπιακών Αγώνων «Αθήνα 2004» (1999) Χωροταξική θεώρηση περιοχών Ολυμπιακών εγκαταστάσεων-υπερτοπικών πόλων ΡΣΑ. Athens.

- ΟΡΣΑ (2003) Σχέδιο Δράσης για την αναβάθμιση της λειτουργίας και της εικόνας της Αθήνας-Αττικής του 2004. Αθήνα.

- Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλίας ΟΡΣΑ (1998) Ειδικό Στρατηγικό Σχέδιο Δράσης της Αθήνας-Αττικής του 2004. Αθήνα.

- ΥΠΠΟ – ΓΓΟΑ (2003) Μεταολυμπιακή Αξιοποίηση των Ολυμπιακών Έργων. Αθήνα.

- Committee for the Athens 2000 Candidacy (1996) The Athens 2000 Candidacy File. Athens: Committee for the Athens 2000 Candidacy.

- Committee for the Athens 2004 Candidacy (1997) The Athens 2004 Candidacy File. Athens: Committee for the Athens 2004 Candidacy.

- Delladetsimas P-M (2003) The Olympic Village: A Redevelopment Marathon in Greater Athens. In: Moulaert F, Swyngendouw E, and Rodriguez A (eds), Urbanising Globalisation: Urban Redevelopment and Social Polarisation in the European City, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 65–90.