2015 | Dec

Omonia, Sunday night.

Holding my breath for long, like a subterranean wave

a bright, rolling metal step

I showed up suddenly at quarter past eleven

amid the hum of my courtier waves from the depths.Giannis Varveris, Kyliomenos tis Omonias

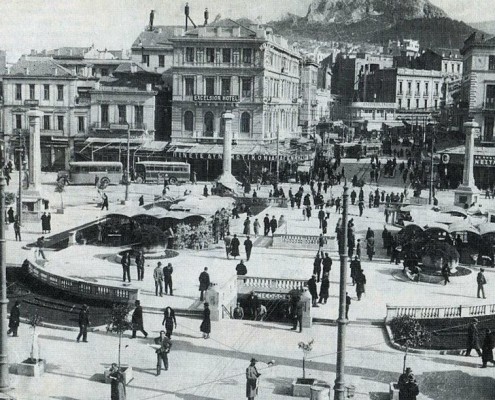

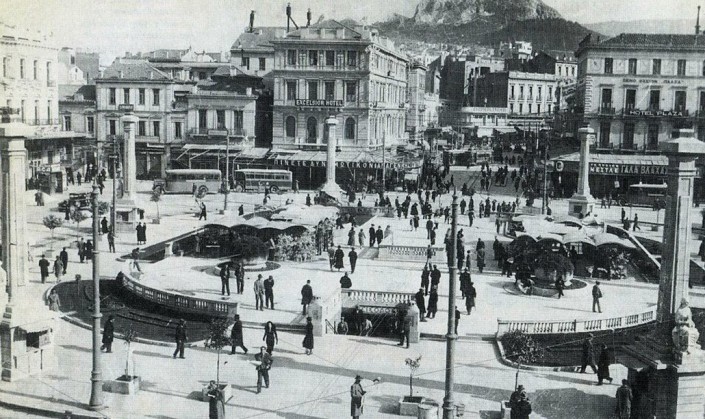

Omonia Square is a bustling place where tourists and immigrants, street-vendors and passers-by bump into each other, passing through it in a rush. This mix of cultural diversity and mirror of social “disorder”, the long-suffering square with its five streets and underground lines, was the Megali Idea [metaphorically denoting a great plan ispired by the national(ist) Great Idea] for every architect and town planner (Κιμπουρόπουλος 1994). The square first appeared in the visionary plan of Kleanthis and Schaubert in the early 19th century and the first house on the square was designed and built by Lysandros Kaftantzoglou at around that time. , More recently, Konstantinos Doxiadis envisioned Omonia as an uptown thoroughfare for travellers and passers-by on the way to the port. Throughout its history this ill-fated square has suffered great tribulations: from the palm trees and the statues of the Muses in the early 20th century to the fountains and the ‘Runner’ statue a few years ago. Currently, at the beginning of the 21st century, Omonia is no longer a square but has been transformed into an extension of the surrounding streets (Photos 1-4).

The square was a cosmopolitan meeting place for middle-class Athenians until the Second World War, with many large hotels such as the currently derelict Megas Alexandros and the Bageion Hotel, watching over its changes and conversions. , Omonia Square was the canvas for any modernisation project attempted on each new page of Greek history. The changes began in the interwar period, when the Omonia underground station on the electric railway line linking Athens to Piraeus was redeveloped, and continued apace after the war, in the late 50s, when Athens witnessed dramatic changes. The square became a transport hub and priority was given to the use of private cars and to finding space at any price (Σαρηγιάννης 1994). Above ground, high buildings were rising everywhere, radically changing the urban landscape, while, below ground, another square with banks and shops was built for pedestrian use. The two squares were linked by escalators and Omonia became a landmark of the city: the Bakakos pharmacy served as the meeting place for all internal immigrants pouring into the capital to live the Athens Dream of post civil war Greece. Extending beyond the confines of a square, Omonia became a place (Photos 5-7).

The square is located at the one end of Stadiou Street, which links Syntagma Sq, Klafthmonos Sq and Omonia Sq. and is geographically defined in relation to the Acropolis, the most prominent symbol of the city. It has found its place in the collective consciousness as another type of symbol, as the capital’s “hub”: a hangout and a crossroad, a meeting place and a hideout, Omonia Square has become a modern Tower of Babel and ultimately, a monument. Primarily however, it has become an urban field through which all social classes, races and ages cross. This heterogeneity is clearly manifested in the roads radiating from the square.

To start with the colourful Athinas Street hosts the Varvakios Agora (Athens’ Central Groceries Market) and connects the square with Monastiraki and by extension with the Acropolis. It also leads to a street which until a few years ago was host to several cheap, run down ‘rent by the hour’ hotels, used, by prostitutes and their customers. Just after that, to the east, there is Stadiou Street, linking Omonia square with the two other legendary squares mentioned above and, then Panepistimiou Street, the street of the Athenian Trilogy connecting Omonia with the Old Palace, which the Kleanthis plan originally situated in Omonia.. After Panepistimiou, the charmless Tritis Septemvriou Street, with no notable features except the stately Victoria Square.Indeed, how could Tritis Septemvriou have notable features when the “great” Patission Street runs parallel to it? Just a hundred metres from Omonia Square, we find more ‘rent by the hour’ hotels and a red-light district in the disreputable – and busy – Lavrio Square. Just beyond that, there is Agiou Konstantinou Street which leads Omonia to the national highway network but also where the National Theatre is located. Finally, Piraeus Street, an industrial street leading to the port.

Omonia Square is seen by the urban consciousness of society as a boundary not only as a junction of five streets, a meeting place, a thoroughfare, a non-place, a home for the homeless and the marginalised, a familiar cinematic, literary scene or a “turbulent zone” (Σημαιοφορίδης 2005);.

This is not a dialectic relationship between the ‘inside’ and the ‘outside’ as in the Bachelard phenomenology of space (Bachelard 2004). It is a boundary that separates the parts ‘above’ and ‘beneath’, cutting the city in half, as narrated by G.Theotokas in Argo, a vivid description of a run down, poor neighbourhood at the beginning of Lenorman Street, in Kolonos, during the inter-war period. In this novel, the author, describing a neighbourhood cut off from the rest of the city, actually described a city cut in two different and diametrically opposed parts as regards their social make-up and cultural identity: beneath the railway, there is poverty and misery, and above it, the inter-war eudemonism dominates in a new Athenian Belle Epoque (Θεοτοκάς 2006)

This is the case here, too. ‘Beneath’ Omonia Square, the “dark side of the city”, as termed by Walter Siebel (Siebel 2003) prevails, where illegal or semi-illegal activities take place, unfamiliar roads with old abandoned buildings host homeless people, the noisy by-streets of the morning turn dark and dangerous in the evening, stimulating the curiosity of reckless night-wanderers.. In this part of town, we find the once bourgeois and now impoverished Vathis square, a hangout for modern fatal adventurers, immigrants, bodies and souls destroyed by drugs, brothels on Acharnon and Liosion Streets. ‘Beneath’ Omonia Square, there is Kolonos, Kerameikos, Votanikos and Metaxourgeio, full of garages and brothels occupying old decrepit neoclassical houses as well as some scattered “alternative” (as they style themselves) entertainment venues, which seem to be trying to forcibly change the identity of those areas. This is where traffic arteries leading to the industrial area of Athens and the Western Suburbs start (photos 8-13).

‘Above’ Omonia Square, we find a contrasting city, with a totally different cultural and social character, another topography, with spatial structures of urban space shaped by the variety of events and consumption semiotics of its users . This is a place of lights, decorations and colours, the historic centre of Athens, the commercial core, Syntagma Square with fancy shops on Ermou Street, the great Vasilissis Sofias boulevard with its luxurious apartment blocks, a place with European cafés and restaurants, afternoon stopover hangouts where regular clients relax after work, expensive jewellery shops, major theatres and cinemas, public services, the Concert Hall, the Hotel Grande Bretagne, the Hilton and other prestigious buildings. The part ‘above’ Omonia also hosts the respectable neighbourhoods of Kolonaki, Plaka and Mets, as well as those along Kifisias Avenue all of them a symmetric opposite of the western suburbs. It is therefore not surprising that unsuspecting walkers suddenly find themselves in another capital, where the lifestyle of the residents seems to ignore the life ‘beneath’ the square. (photos 14-20).

Even so, even if it is a boundary between two “worlds”, we should also understand Omonia Square as an omniscient narrator of the city. An author who writes in the morning whatever takes place at night. In its dark corners and silent galleries, in its morbid streets and sad buildings, among the shadows that inhabit it and the escalators that lead from one part of the city to the other, sometimes leaving their tracks on its thick concrete skin and sometimes erasing them, on the breathless tarmac and its “electrified” bowels.

Entry citation

Andriopoulos, T. (2015) Omonia square as a limit and a narrator, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/omonia-square/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.24

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Bachelard G (2004) Η ποιητική του χώρου. 3ο έκδ. Χατζηνικολής (επιμ.), Αθήνα.

- Siebel W (2003) Τα θεμελιώδη χαρακτηριστικά και το μέλλον της ευρωπαϊκής πόλης. Στο: Λέφας Π, Siebel W, και Binde J (επιμ.), Αύριο οι πόλεις, Αθήνα: Πλέθρον, σσ 67–105.

- Θεοτοκάς Γ (2006) Αργώ. 20ο έκδ. Αθήνα: Εστία.

- Κιμπουρόπουλος Γ (1994) Η «Ομόνοια» όλων των Ελλήνων. Επτά Ημέρες, Η Καθημερινή, Αθήνα, 23ο Ιανουάριος.

- Σαρηγιάννης Γ (1994) Αθηναϊκό σταυροδρόμι. Η κοινωνική σύνθεση και οι χώροι συναθροίσεων των Αθηναίων στην πολύπαθη πλατεία. Επτά Ημέρες, Η Καθημερινή, Αθήνα, 23ο Ιανουάριος.

- Σημαιοφορίδης Γ (2005) Διελεύσεις. Ανανιάδης Δ (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Metapolis Press.