2015 | Dec

The collection of imperial orders in the Prime Minister’s Ottoman Archives in Istanbul include a colour manuscript map of Athens. It is classified under the title “Plan of the Castle and City of Athens” (Atina kalesiyle varoşunun krokisi) and is the only Ottoman map of the city that we know of.

It measures 141.5 x 112 cm, but, as it has remained folded for years, it bears visible signs of moisture and discolouration. All the signs and names on the map are written in the Ottoman language, including the inscriptions in the two rectangular frames, on the top right and left. The cartographer remains anonymous.

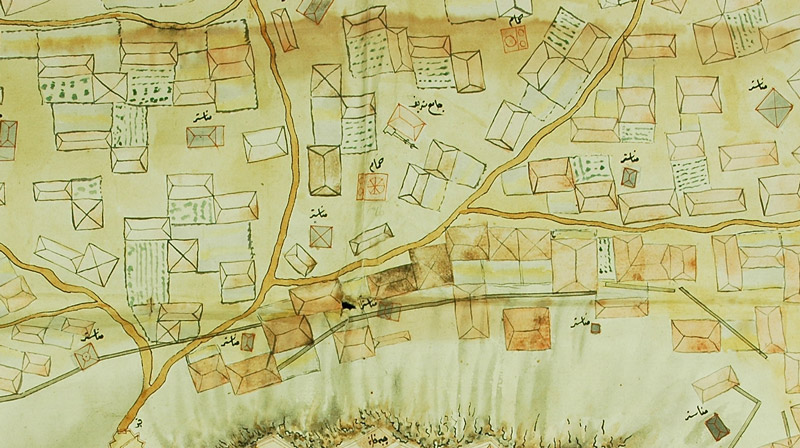

Figure 1: The orientation of the map

The map is oriented NE-SW and it displays the area inside the walls of the city of Athens. This is the so-called “Wall of Haseki”, named after the voivod of Athens from 1774 to 1795. It was built in 1778, over a very short time (sources mention a period of 70 to 108 days) and many Athenians were forced to work for its construction. The cartographer has marked all the towers along the wall, as well as six gates. It is noteworthy that the cartographer does not appear to be familiar with the various names in Greek and Turkish that various sources mention for each of the seven gates of the wall of Athens,for example the gate in the Acropolis was called the Castle Gate, the Mnimaton Gate or the Karababa Gate. On the contrary, the names used in the map are completely new, providing very interesting information about the topography and place names of Athens and of course about the cartographer’s relationship to the city.

The roads inside and near the walls are mapped in detail, with the word tarik (road) often appearing next to the thick lines indicating roads. To the southeast, a dotted line marks the river Ilissos, here called Kuru Dere (Xiropotamos). It shows the relieve around the rock of the Acropolis, the Pnyx and the Hill of the Muses in the southwestern part of the city. The cartographer used thick black lines to designate the rocky hills that housed many military facilities and bastions.

Groups of dots and dashes around the city walls designate vegetation, while, inside the walls, the map becomes more accurate, showing colour drawings of houses with roofs and gardens. The map was drawn without a three dimensional perspective. It therefore follows the tradition of mid-18th century Western cartography, in which the dominant way of displaying city plans was to use carefully delineated streets and outlines of buildings. In the Ottoman map of Athens we see roofs, gardens, trees and domes, presented as circular and rectangular shapes. There is one exception, concerning the minarets of mosques, which have been sketched with all their architectural details and appear adjacent to the mosques.

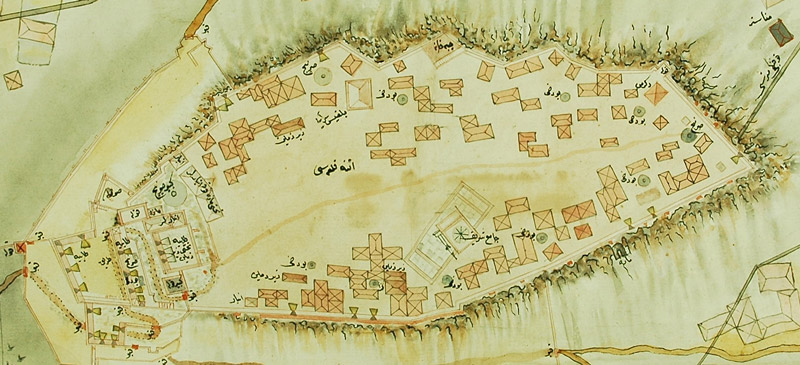

Figure 2: The central area of the city of Athens, known today as Plaka-Monastiraki

While black ink was used to mark the outline of houses, non-residential buildings, which include mosques, churches, baths etc. have a red outline. Specifically, Ottoman public buildings (mosques and baths) have a red outline and no fill, while churches and temples have a red outline with a grey background. One of the interesting aspects of this map is that it does not provide the names of the buildings appearing in it. Although there are design details that distinguish the buildings depending on whether these have domes or flat roofs, churches are all designated as monasteries (manastır) and mosques simply as holy mosques (cami-i şerif).

The absence of building identification and the indifference to monumental architecture are particularly noteworthy: the rock of the Acropolis is simply described as “The Castle of Athens”. The Parthenon is displayed without attention to detail, while its orientation is wrong (its axis has shifted to the NE-SW direction). Moreover, the only labelling provided concerns the mosque that had been built inside the Parthenon, but this is not designated in any distinctive manner either: it is just another holy mosque.

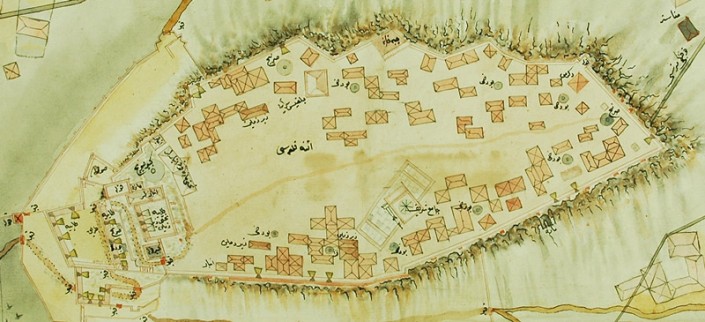

Figure 3: The rock of the Acropolis

Besides the Parthenon, several small houses have been depicted on the rock of the Acropolis. Their existence had also been recorded in the texts and drawings of contemporary travellers. The Acropolis was a small village, where the soldiers of the Ottoman garrison and their families lived.

The cartographer placed more emphasis on buildings and structures that could be useful for military purposes. Therefore, all water tanks are marked in detail and so are towers and ammunition depots, bastions, underground bunkers and gates. Points of military interest are also marked in areas outside the Acropolis: bastions with cannons, protective walls opposite the entrance to the castle, long trenches for riflemen and many similar military facilities on the hills of Pnyx and Filopapou.

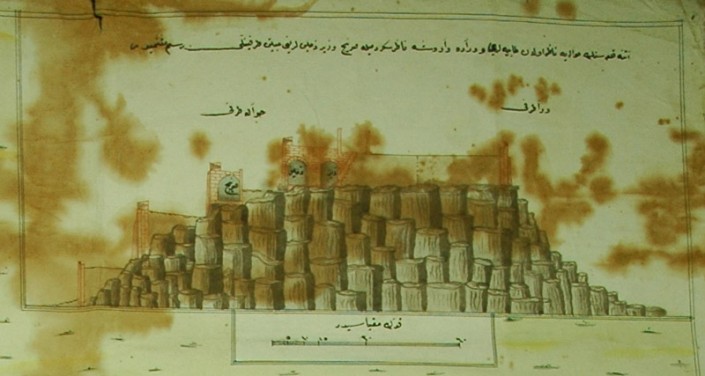

In the upper right corner of the map, there is a rectangular frame with a lateral brown and red drawing of the fortification of the Acropolis, along with a measurement scale. The inscription indicates that this is the plan of two aspects of the castle of Athens,one of the bastions and the protective wall and one of the city side. This drawing also shows the fortifications, the water tank and the underground rooms located there.

Figure 4: Drawing in the upper right corner – the rock of the Acropolis and its fortifications

The main inscription of the map is in the upper left corner. Here we read the description: “This is a Map of the Castle of Athens including the city and the protective wall, conquered with the help of Almighty God”. This is followed by the date 11 Zilkade 1242 Hegira year, corresponding to 6 June 1827.

During the Greek War of Independence, the Castle of the Acropolis surrendered to the Ottomans, led by Kütahı (Reşid Mehmed Paşa), on 25 May 1827, following a 10 month siege… This Ottoman map, which is purely military in nature, was probably drawn during the siege, perhaps based on other maps of western origin, as a useful tool in the battle and later, after the conquest, was sent and offered to Istanbul announcing the victory.

Athens, as displayed in the map, was a small town with tiled roof houses, green gardens, many churches, a few tightly clustered Ottoman public buildings, a castle with strong fortifications and a wall that surrounded it tightly but also well connected, with several gates leading to inland and coastal destinations.

* the figures show details from the map

Entry citation

Stathi, K. (2015) Athens in the Ottoman map of 1827, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/ottoman-map-1827/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.34

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Κορρές Μ (2010) Οι πρώτοι Χάρτες της πόλεως των Αθηνών. Κορρές Μ (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Μέλισσα.

- Σκουζές Π (1948) Χρονικό της σκλαβωμένης Αθήνας στα χρόνια της τυραννίας του Χατζή Αλή γραμμένο στα 1841. Βαλέτας Γ (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Κολολού, Α.

- Bessan JF (1835) Souvenirs de l’expédition de Morée en 1828: suivis d’un mémoire historique sur Athènes, avec le plan de cette ville. 1st ed. Valognes: Gomont.

- Eyüpgiller KK (2004) Atina Akropolü’nde bir cami. Mimarlik Tarihi, Oct 100: 118–121.

- Stathi K (2014) The Carta Incognita of Ottoman Athens. In: Hadjianastasis M (ed.), Frontiers of the Ottoman Imagination, CHAP, Leiden, Boston: Brill, pp. 169–184.

Archival source

- BOA, HAT 946.40721