Piraeus 1951-2011: demographic stagnation within a vibrant metropolis

Maloutas Thomas

Built Environment, Quartiers, Social Structure

2017 | Feb

Compared to the rest of central city areas, the Municipality of Piraeus (DP) appears demographically stagnant since 1950 [1]. In fact its population reached 193.000 in 1928 (Bournova, 2016) and presented small changes since. This course is very different from the strong increase followed by the important population decline in the Municipality of Athens (DA) or from the steady population increase of municipalities around both DA and DP (figure 1).

Figure 1: Population change in the central municipalities of the Athens metropolitan area 1951-2011 (thousands of inhabitants)

Municipalities around DP: Nikaia, Korydallos, Keratsini, Drapetsona, Perama, Ag. I. Rentis

Municipalities around DA: Vyronas, Galatsi, Dafni, Zografou, Kaisariani, Kallithea, Nea Smyrni, Ymittos

Source: ELSTAT, Population cencuses (https://panorama.statistics.gr/)

The demographic stagnation in absolute numbers in the Municipality of Piraeus has not at all followed the rapid population increase of the whole metropolitan area (figure 2) during the post-war period (Kotzamanis, 1997).

Figure 2: Population change in the Athens metropolitan area (Attiki Region) 1951-2011

Source: ELSTAT, Population cencuses (https://panorama.statistics.gr/)

A more detailed look reveals that the Municipality of Piraeus and, more or less, the municipalities surrounding it, show a slight population decline after 1980, which is slightly reversed in the 1990, to appear again in the 2000s. This trend is not very different from what happens in the Municipality of Athens and its neighboring areas, since all the central areas of the metropolis seem to experience a decline of their population after the 1970s. The decline of these areas’ specific weight is mainly due to the city’s expansion and to the gradual move of housing to the suburbs.

The population decline for the two most important central municipalities appears more important when calculated on a relative basis, i.e. as their changing percentage in the total population of the metropolis. The profile of central areas becomes thus a profile of clear and continuous decline (figure 3). The percentage decrease in the specific population weight in the metropolis’s total population during the period 1951-2011 is greater for the Municipality of Piraeus (-68%). The population of the Municipality of Athens is reduced by 57% and that of municipalities around it by 12%, while the population of municipalities around Piraeus was reduced by 34%.

Figure 3: Population percentage of central municipalities in the total population of the metropolis (Attiki Region) 1951-2001

Municipalities around DP: Nikaia, Korydallos, Keratsini, Drapetsona, Perama, Ag. I. Rentis

Municipalities around DA: Vyronas, Galatsi, Dafni, Zografou, Kaisariani, Kallithea, Nea Smyrni, Ymittos

Source: ELSTAT, Population cencuses (https://panorama.statistics.gr/)

One can refer to various parameters explaning the demographic evolution of the two main centres of the metropolis and the areas around them. Piraeus, first of all, did not have the amount of vital space to expand as the Municipality of Athens did, both in quantitative and qualitative terms. The Municipality of Piraeus was rather densly built since the beginning of the period in question; at the same time, it did not possess the necessary urban (e.g. large road axes) and economic preconditions (level of land values) except in its most central areas, which however were quite developed already. The municipality’s periphery, as well as most of its surrounding areas, were the places where working-class self-promoted housing –often informal and illegal– was being developed. The concentration of working-class housing and the particular processes through which it was produced, led these areas to acquire a social and urban profile that was not favorable for the production of the standard middle and lower-middle class apartment building (polykatoikia) which proliferated in and around the Municipality of Athens in the 1960s and the 1970s.

The difference in population trends between the two centres appears to be that while the centre of Athens was totally coordinated with, and largely contributed to, the rapid population growth in the 1950s and the 1960s, the population in the centre of Piraeus remained rather stable and without any important fluctuation in the course of 60 years. This difference is clearly reflected in the building dynamic that characterises the two centres: the centre of Athens was massively built between 1946 and 1970 using the flats-for-land system (antiparochi) [2] and became the main concentration area of modern housing for the city’s middle and upper-middle strata. The centre of Piraeus followed a decade later, when the negative impact of this housing production system had started to become clear, and the housing preferences of middle and upper-middle strata had already turned massively to suburban locations in the north and the south of the agglomeration. Figure 4 shows clearly Piraeus’s lagging behind in the process of modern housing production.

Figure 4: Percentage of residents in house buildings in the Municipalities of Athens and Piraeus by the period these buildings were produced (2011)

Source: ELSTAT, Population census 2011 (https://panorama.statistics.gr/)

If the stability in the evolution of the population of Piraeus during the period of the dynamic growth of the metropolis (19050-1980) is due to the reasons mentioned above, its rather small decline after 1970 should mainly be attributed to the particular sectors of the economy located almost excllusively in Piraeus (e.g. related to shipping and the port) and to the fact that the move to the suburbs was more difficult for the middle-classes of Piraeus than for those of Athens. The broader periphery of Piraeus has very few residential areas desirable for its middle and upper-middle classes, while those in the norther and southern suburbs and in eastern Attiki are quite distant for commuting.

Commuting for work, for example, towrds the Municipalities of Athens and Piraeus in 2001 from suburbs highly ranked in terms of land values, [3] reveals the following situation: 38.651 towards Athens and 4.806 towards Piraeus (almost twice as large a flow to Athens taking into account the respective population of the two municipalities). Another facet of this comparison is shown in figure 5, where the greater difficulty to commute towrds Piraeus from the northern suburbs is clearly demonstrated.

Figure 5: Number of commuters moving daily for work to the Municipalities of Athens and Piraeus by 1.000 inhabitants and by municipality of origin (2001)

Source: ELSTAT, Population census 2001 (https://panorama.statistics.gr/)

The breadth of migrant groups’ inflow during the 1990s is one more feature differentiating the demographic stability in Piraeus with the marked changes in the Municipality of Athens. The population decline in the latter between 1991 and 2001 (-2%) occurred in spite of the important inflow of migrants from Eastern Europe and from developing countries outside Europe whose percentage reached 16,2% of the Municipality’s population in 2001. On the contrary, the population increase in the Municipality of Piraeus during the same period (5,3%) depended much less on the increase of migrants who reached 8,4% of the Municipality’s population in 2001. The two Municipalities showed similar trends in the 2000s. Migrants (excluding citizens of developed economy countries) in 2011 reached 20,8% in the Municipality of Athens and 9,4% in the Municipality of Piraeus.

It is obvious that what appears as demographic stability or stagnation in Piraeus during the last decades is a phenomenon depending on multiple factors which cannot be examined in isolation from trends in the rest of the metropolis. It is also obvious that devising policies aiming at a new growth –not only in demographic terms– cannot rely also on unidimensional analyses and assumptions.

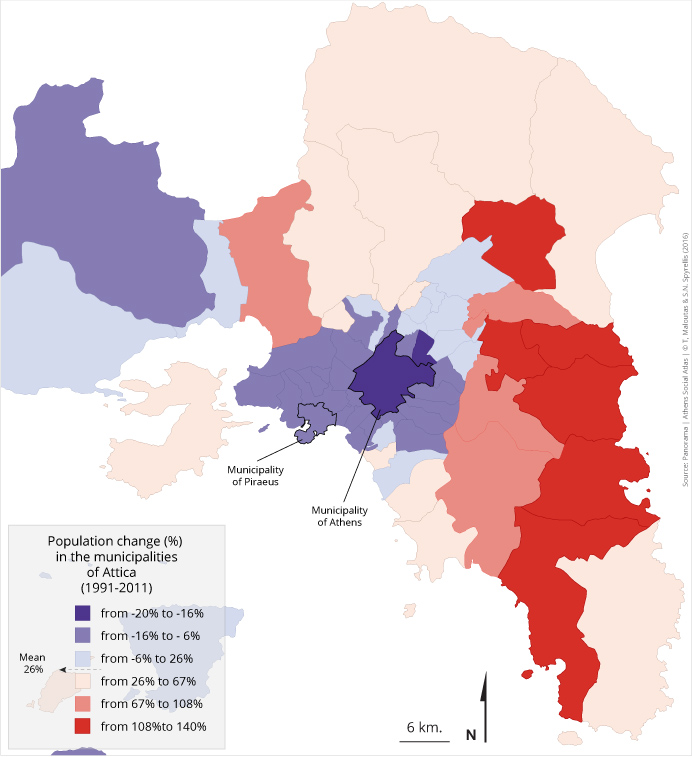

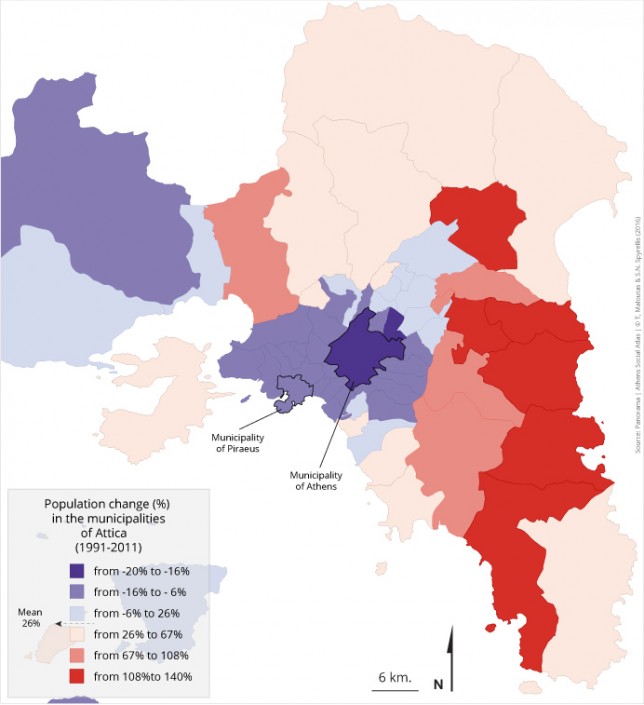

Map 1: Percentage population change in the Municipalities of the Region of Attiki between 1991 and 2011

[1] A previous version of this text was published at the first volume of ‘Π’ (Piraeus) magazine, March 2011, p. 7-9.

[2] The flats-for-land system is a barter system based on an agreement between a land owner and a builder-contractor to construct a building and split the ownership of the apartments and/or offices and shops built, as per an initial contract describing each side’s level of participation in the relevant investment.

[3] Commuting to the Municipalities of Athens and Piraeus was registered, using the 2001 Census, from the Municipalities of Kifissia, Psychico, Filothei, Ekali, Ag. Paraskevi, Chalandri, Amarousio, Glyfada, Vouls and Vouliagmeni.

Entry citation

Maloutas, T. (2017) Piraeus 1951-2011: demographic stagnation within a vibrant metropolis, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/piraeus-demographic-stagnation/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.69

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Κοτζαμάνης Β (1997) Αθήνα, 1848-1995. Η δημογραφική ανάδυση μιας μητρόπολης. Επιθεώρηση Κοινωνικών Ερευνών 92–93: 3–30. Available from: http://ejournals.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/ekke/article/viewFile/7291/7011.pdf

- Μπουρνόβα Ε (2016) Οι κάτοικοι των Αθηνών, 1900-1960. Δημογραφία. Αθήνα: Εθνικό και Καποδιστριακό Πανεπιστήμιο Αθηνών, Εθνικό Κέντρο Τεκμηρίωσης. Available from: http://ebooks.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/econ/catalog/view/4/10/110-1