Going down Piraeus Street: the metamorphoses of a street, witness of industrial Greece

Bournova Eugenia|Gouzi Vincent

Economy, History

2023 | Jun

| « Κατέβην χθές εις Πειραιά μετά Γλαύκωνος του Αρίστωνος… »

Plato, The Republic |

What visitor of past centuries Greece has not traveled across the space between the port of Piraeus and the Acropolis? What careful observer today does not see that the site has hardly changed: from the escarpments of the Acropolis, he takes a direct view of the sea and descends the gentle slope of the “basin” taken between Hymettus and Aigaleo to the coves of Piraeus. This articulation of the hinterland and the maritime space constructs the economic space, whether it is a question of ancient Athens which built the “Long Walls”, of the Bavarian city which finds the old route building as soon as 1836 the new one, or of the current metropolis.

Map 1: Map of Athens Piraeus with the lay out of the Long Walls

At independence, Othon assigns Kleanthis and Schaubert in 1834 the task of designing the street, as part of an extensive urban plan. Finally, a less ambitious task is entrusted to Léo von Klentze and a stone road is built in 2 years and opened in 1836. The Elektriko, parallel to this road, was inaugurated in 1869. On the other side, a railway line was built in 1884 (Peloponnese Station), closed in 2005 and replaced by the current Proastiako.

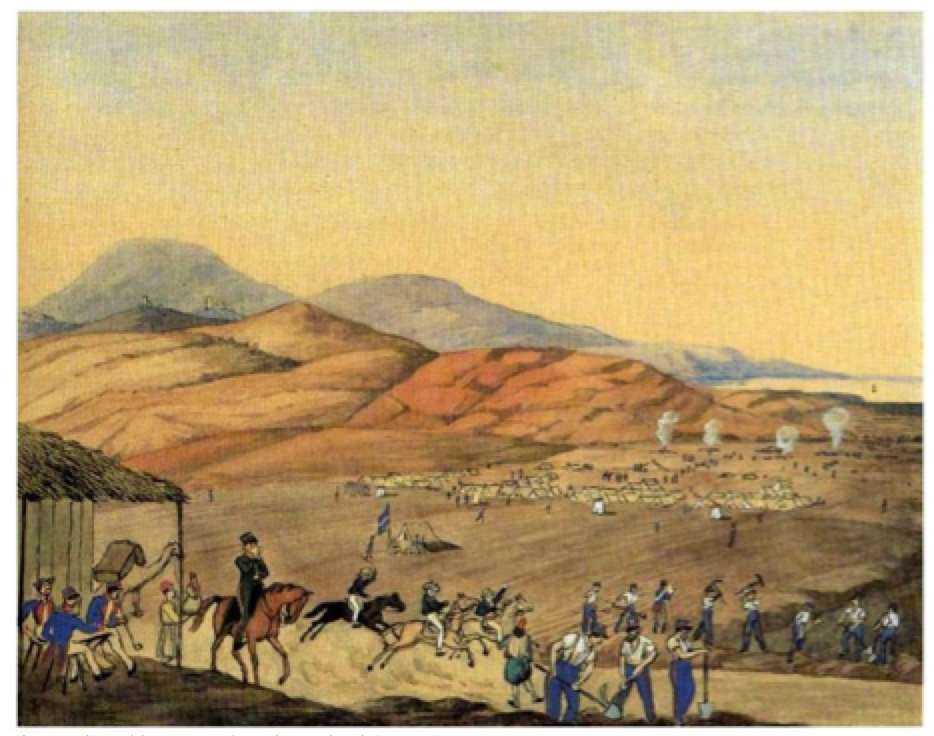

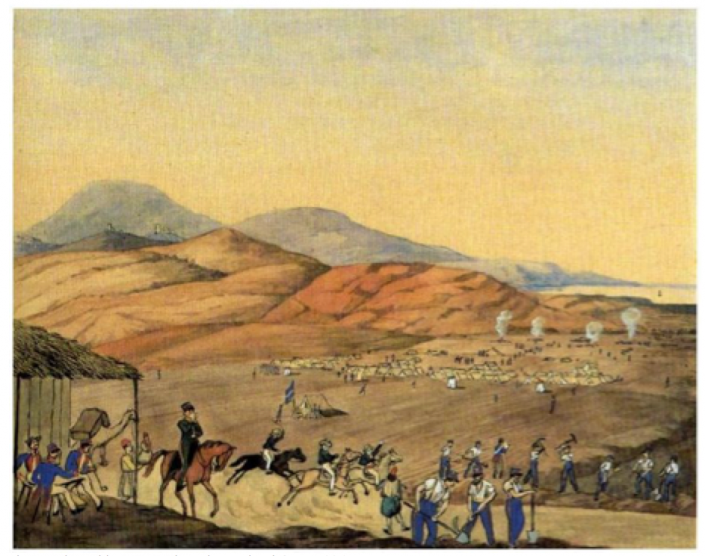

The map above is an adaptation of that of J.A. Kaupert (Karten von Attika, 1882) and shows the low land use at that date. The watercolor below (Bivouac of the soldiers building the Piraeus Street in 1836) is from Köllnberger, borrowed as well as his commentary to the leukoma of Jean Meletopoulos, “τα πρώτα έτη της οθωνικής εποχής εις τας υδατογραφίας του Köllnberger”, edited by the Historical Society of Greece.

Photo 1: Bivouac of the soldiers building the Piraeus Street in 1836

Rushing down by car the 8 km that separate Omonia Square from the Piraeus hill, one gets a first glimpse, expressive already of this space-time of the Greek economy. Piraeus Street was the main axis of development until the first decades of the post-war period, gradually occupying the land between the city and its port. Its history is linked to that of the capital and of the economic development, particularly industrial, of the country.

The data available allow us to follow its transformation since the interwar period, by making three historical cuts: on the eve of the Second World War (with Nikolaos Iglesis’ guide of 1939), immediately after the war (with the guides of N. Iglesis of 1947-48 and of 1957, the Telephone Directory, catalog of subscribers of 1948, the study of Sideris of 1948 [1] and the maps of Diamantopoulou of 1955 [2]), all completed in the years 2014-2020 by a field survey.

The current street is wide, with 4 lanes separated by a central reservation. It is bordered by two railway lines, on the left the Elektriko and on the right the current Proastiako [3]. Communication channels are fluid and businesses are well served.

It runs along the plain of Elaionas, the ancient olive grove, watered by the Cephissus and its tributary the Parapotamos (or Prophiti Daniil) and by the Ilissos originally swelled by the Eridanus descending from Lycabettus. This vast basin (Lekanopedio) remained a rural and low-density area for a long time: photos show that until the 1950s there were many open spaces and gardens. It was a market gardening area supplying fruit and vegetables to the rapidly developing conurbation. The Athens Vegetable Hall (the fruit and vegetable market or Lachanagora), driven back from its former location at the corner of Iera Odos, naturally settled there on the right in 1955, a little before the Cephissus, and the slaughterhouses (Sphagia) moved in 1920 from Chamosterna to Tavros, on the left, before being handed over to private ownership. The basin opens onto the Gulf of Faliros, where flow the Cephissus and the Ilissos, a short distance from each other.

Methodological issues

The first problem encountered is that of numbering. Piraeus Street crosses municipalities (demes) which have each decided on its name and the numbering of the buildings that border it.

It thus falls under 5 different municipalities [4]: following a complicated cutout, those of Athens and Piraeus and, between the two, those created at the time of the influx of refugees from Asia Minor, Tavros, Moschato and St John Rentis. The demes of Tavros and Moschato were created in 1925 and 1934 respectively, before being united according to the Kallikratis reform in 2011, and that of St John Rentis, created in 1925, has been united in 2011 with the deme of Nikaia. Piraeus Street is called Panayi Tsaldari in Athens, Pireos in Tavros, Moschato and Saint John Rentis and Athinon-Pireos in Piraeus.

The numbering of the buildings reflects this administrative “Meander”. The numbers increase going down Piraeus Street, even on the right and odd on the left, from Omonia Square up to and including the Moschato Deme and up to Sikiaridi Street. But the demes of Rentis and Piraeus have chosen a decreasing numbering, odd on the right and even on the left and each their own. In addition, if the new buildings have adopted recent numbering, the old ones have often kept their original number on their plate!

Map 2: The evolution of numbering on Pireos street

Map 2: The evolution of numbering on Pireos street

A second problem is that of identification. Assigning establishments, a company name, a date, a place, and an economic activity is a laborious and imperfect exercise, which involves a step-by-step exploration of the field. The name of the company is not always obvious. Greek industrialists avoid the plates, evade any investigation. A stranger asking questions at the entrance of a building, notebook in hand, immediately arouses mistrust. Fortunately, we have many pieces of documentation: the list of 88 listed buildings [5], the guides cited above, data gleaned from company sites, various studies cited in the bibliography.

The establishments sometimes face the Piraeus Street, sometimes the perpendicular or parallel streets, which allow discoveries. The fact remains that the street is scattered with many unvalued spaces or vacant lots, which are difficult to identify. The transformation process was slowed down by administrative procedures and by the crisis of the years 2009-2019. Some pieces of land are blocked by archaeological excavations. The low percentage of residential buildings in the total (in linear meters), including retail businesses, is characteristic, which matches the low number of telephone lines.

The street in the 1930s-1950s

Τα αρχεία που χρησιμοποιήθηκαν για την μελέτη αυτής της περιόδου – Εμπορικοί Οδηγοί του Νικ. Ιγγλέση από το 1939 έως το 1957 και ο τηλεφωνικός κατάλογος του ΟΤΕ του 1948 – δεν μας επιτρέπουν να μελετήσουμε όλους τους κατοίκους της Πειραιώς τις παραμονές του 2ου Παγκοσμίου Πολέμου. Όμως οι διαθέσιμοι χάρτες επιβεβαιώνουν ότι το τμήμα του δρόμου που ξεκινά από την πλατεία Ομονοίας και καταλήγει στο Γκάζι είχε πολλά σπίτια. Φυσικά, ο τηλεφωνικός κατάλογος μας επιτρέπει να εντοπίζουμε μόνο τους κατοίκους που έχουν τηλεφωνική σύνδεση, άρα μάλλον καταστήματα και επιχειρήσεις παρά κατοικίες.

The archives used for this period – Igglesis professional guides from 1939 and 1957 and OTE Directory from 1948 – do not allow us to study all the inhabitants of the Piraeus Street on the eve of the 2nd World War. But available maps confirm that the section of the street that begins at Omonia Square and ends at Gazi had many houses. And of course, the Telephone Directory only allows us to sketch those of the inhabitants subscribed to the telephone.

The most common businesses in 1939 were the cafés: there were 26 of them, of which only 4 had a telephone line in 1948. In the 1948 telephone directory, the cafés with a line were only 6, which can be explained by the high subscription costs, for establishments most of which were modest and could not afford it. Even in 1957, 18 street cafés did not have telephones. Thus, if our sources do not betray us, the greatest change in the street between 1939 and 1957 (table 1) seems to be the strong growth of industrial manufactures and the reduction of the liberal professions which moved to other streets: there were only 14 doctors due to the presence of Municipal Maternity and 8 dentists. The 10 lawyers from 1939 have moved away in the meantime, another indication of the changing character of the street.

Table 1 : Activities in Piraeus Street from the 1930s to the 1950s

Source : The N.Igglesis guides of 1939, 1948 and 1957 and the Directory of telephone subscribers

Less than half of professionals have telephone lines (graph 1). Although the percentage rose from 25 to 45% in the first decade after the war, it then fell to just under 40%. The total number of lines will rise from 152 to 202 from 1939 to 1957, but remains however well below that of the capital, the total of which increases from 28,000 before the war to 75,000 in 1956, again witnessing the low density of Piraeus Street population.

Graph 1 : Percentage of telephone professional subscribers between 1939 και 1956 Source: The Directory of telephone subscribers

Source: The Directory of telephone subscribers

In fact, in the mid-1950s, Piraeus Street became the quintessential industrial street of Athens. Beyond the few neoclassical buildings in the Omonia area, begins the Gazi area; Continuing the descent towards the port, we encounter a proliferation of factories (graph 2&3).

From 152 factories counted in 1939, there were 272 in 1957: this strong growth signals the industrial growth at the beginning of the post-war boom period.

Graph 2: Percentage of Liberal Professions between 1939 and 1956

Graph 3: Piraeus Street Industries & Manufactures between 1939 και 1956

Source: The N.Igglesis guides of 1939, 1948 and 1957

Behind the figure, one must discover, step by step, the reality of the activities, in 6 stages which correspond to relatively coherent sets.

The evolution of activities along Piraeus Street

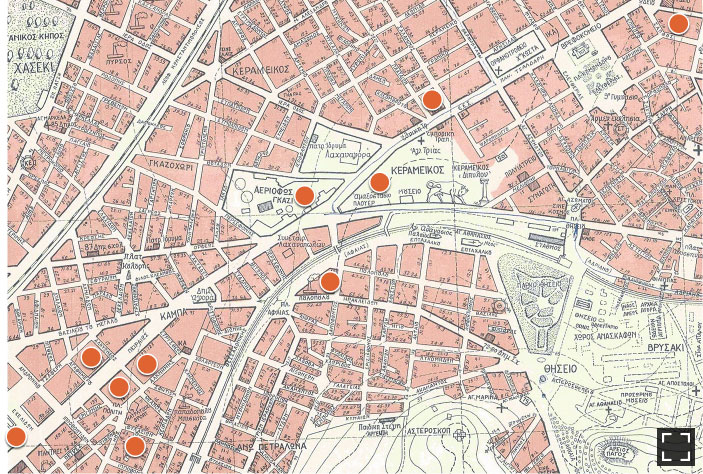

Map 3: the zones of interest in Pireos street

1st zone: From Omonia Square to the Iera Odos-Ermou crossroad.

According to the 1939 Igglesis guide, the street begins at the Athens Polyclinic at No. 3. Then there is the Municipal Conservatory at 35, at 51 the Municipal Orphanage of 1859, at 68 the Hadzikonsta Orphanage which will be destroyed in 1963 and replaced by the only church of Saint Georges, at 77 before the war the hospital of the Panhellenic Alliance against Tuberculosis, at 24 the care center of Antoine Spirla and between 7 and 71, 25 doctors, 5 dentists and 8 pharmacists, including the ophthalmologist A. Anastopoulos who seems to have held a clinic at 50. Also 10 lawyers, 3 banks (Commercial, Popular and Agricultural, near the Athens Vegetable Hall), 3 real estate agents and service agencies, 8 hotels, 15 tailors, numerous hairdresser and hairdresser shops, numerous cafes, and dairies. And due to the spread of cars, 10 garages, auto accessory stores and gas stations. The Vegetable Hall was at 100, at the corner of Iera Odos and Tsaldari, before it was moved in 1955 to Rentis.

In this segment, also in 1939, one could find 260 establishments, particularly industrial. These were not located only in the street of Piraeus, but in the perpendicular or parallel streets. They constituted a district called the Metaxourgeio [6], with a clear mechanical specialization. On Piraeus Street at 84, there was the spring factory of the Perdios brothers (1935) and on the left that of the weighing equipment of the Moschountis company (1937). Guides of Igglesis show that in the 1950s the character of industrial craftsmanship of this district had been well preserved. They also mention the Polyclinic of Athens and the Eye (ophthalmic) clinic of A. Anastasopoulos, the luthier E. Tsambourzis at 29, doctors and dentists, hotels, a notary, 7 pharmacies, 6 real estate agents, the headquarters of 6 newspapers, 7 jewellery-watch shops. But the number of tailors and hairdressers has decreased a lot, which suggests that the number of inhabitants has also decreased. The number of cafes has shrunk, but just because they aren’t registered doesn’t mean they don’t exist.

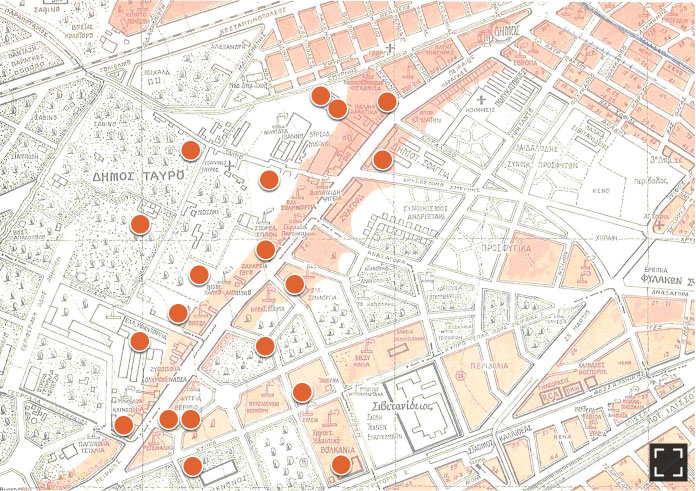

Dynamic map 1: Details on the key industries located on the first zone (Omonia Square to the crossroad Iera Odos and Ermou street)

Source: K. Diamantopoulou, 1955

The extension of the center of Athens has changed the economy of this district. Industrial companies disappeared like Perdios or moved like Moschountis, to Mandra. They have been replaced by hotels, cultural establishments (Pinacoteca, ICOMOS, G. Papandreou Foundation) or leisure establishments (Psyri district, Bios’ café-theatre installed in 2002 in the beautiful Perdios building). Its proximity to the center predestined it for gradual gentrification, especially since small, low but nicely decorated houses, still abound in the adjoining streets. But these often abandoned, and poorly equipped houses have found only recent immigrants as tenants, and this has not been changed by the recent economic crisis. Their presence is particularly visible near the Athens Reception Center.

2nd zone: From Iera Odos to Petrou Ralli

The industrial installations wrap around the rock of Petralona on the left, and on the right overspill Piraeus Street towards the district of Rouf and the Botaniko. This district, farther from the historic center, hosted on the right, around the Fotoaerio (Gazi), mechanical workshops (foundries, metalworking, Ilpap workshop) and on the left luxury industries (Pavlidis and Atsaros chocolate factories, Poulopoulos hat shop, Mendis’s trimmings, Perrakis stationary, Palco weavings), the research center of Edok Eter.

Dynamic map 2: Details on the key industries located on the second zone (Iera Odos street to Petrou Ralli)

Source: K. Diamantopoulou, 1955

About 60 companies were located in this section of the street in 1939, the best known being the D. Pavlidis chocolate factory at 145, and there are no liberal professions except for two civil engineers who work in their own company, D. Pavlidis (Chocolaterie) and D. Sakellariadis (paintings, at 123), a single pharmacy, a dozen café-bistros. For the rest, of mechanics, chemical and food companies. Twenty years later, Igglesis in 1957 notes a single doctor among 70 companies, mechanical workshops (garages), food industries, construction companies.

Today, an active renovation policy carried out on a space well served by means of communication has changed the character of this district. The successful transformation of the Fotoaerio into a Technopolis industrial museum has attracted many leisure centers (nightclubs, fitness) and cultural establishments (museums, theatres, The Cinematheque). Administrative or industrial services (RAE, Cosmote) or events services (The Hub, Metalourgeio) have settled there. The construction of lofts accompanies a change in population: gentrification is advancing rapidly.

3rd zone: From Petrou Ralli to Chamosterna (Tsaldaris)

Benefiting from larger spaces, heavier and more varied industries appeared here before and after the 2nd World War: In 1939 there were about thirty industries: mechanics, piping, paints and resins, furniture, asphalt, but also more traditional industries such as farriery (horseshoes), and along the Ilissos, tanneries, leather goods and saddleries, but also hay sellers. The slaughterhouses at the time are not far away. As in the previous section, this is an industrial district and there is only one café, a pastry chef and three bistros.

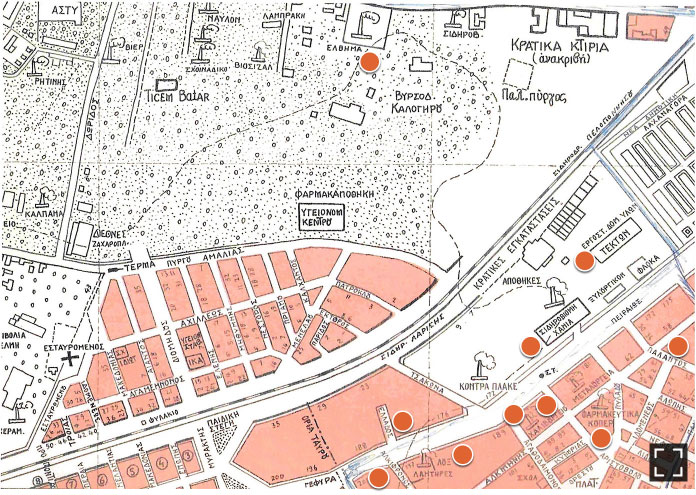

Dynamic map 3: Details on the key industries located on the third zone (Petrou Ralli street to Chamosterna (Tsaldari street)

Source: K. Diamantopoulou, 1955

Twenty years later, this character has been reinforced: mechanics (SPAP), metallurgy (Chalyvourgiki and Chalyvourgia), electrical products (Osram-Loux), pharmacy (Koper), public works (Tekton), paints and resins (Chrotech), plastics (Plastina), generators (Elvyma), Ford garage, Kontra Plake carpentry. There are also some textile industries (Marangopoulou). There are deposits of marble and wood that require space and proximity to the city center.

Today, the district is dominated by large retailers (Praktiker, Athens Heart, Sklavenitis) and administrations (ELAS, Central Army Pharmacy, SDOE, KEDE at 166, which will be replaced by a new building intended for the General Secretariat for Infrastructures). Services to industry appear (Vodaphone, the headquarters of Hellenic Protein Group) or electronic product businesses (Top, AEG), which testify to the evolution of needs. Finally, the proximity to the center explains again the presence of leisure centers, but these are no longer just theaters or nightclubs, but for example the new sports center of Athens, the Serafio.

4rd & 5rd zone: Tavros-Moschato-Renti

In Tavros, between Chamosterna and the “Strophi”, the spaces from 1920 to 1950 are gradually saturated by polluting industries, such as metallurgy (Viochalko, Viosol, Tsaousoglou, ELSO), plastics and rubbers (Boulkania-Petzetakis), tanneries-dyeing close to the slaughterhouses and the rivers already mentioned, (Minas Maiakis, Georgala and Kepetzis, Moumouris, Porphyra, Niagara and Simos) or the textile factories (Sikiaridis, Tziropidis,). Around the Benakis slaughterhouse and the cattle barns of the Zoagora, food related industries are developing, such as the Kalypso and Vermion refrigeration plants, the Bogiatzidis ice factory.

Since then, polluting industries have closed or moved and the effort to revitalize Piraeus Street has passed through cultural institutions (Kakoyannis Foundation, School of Fine Arts, Ellinikos Kosmos) or administrative institutions (Tavros Town Hall, National Center of Public and Local Administration, SG of computer systems). Industry has specialized in food products (Kreon, Ainos), leather goods and household equipment (Hunter, Viopros, Vioper, Constantourakis) and very specialized or advanced small industries, such as Vido Ferro screw industry, the manufacturer of ATE Tzavidas, Olympic Shoe Machinery. We also note the DEI printing. Finally, the installation in 2008 of Teleperformance, a telephone marketing company, and its meteoric development – it employs nearly 6,000 people here, spread over 4 sites – characterizes the successful shift of the industry towards services to industries and the capacity of Piraeus Street to renew itself, partly using local workforce. Identical observation for the software designer CPI, listed on the stock exchange, for Image Works, an electronic printing company or for ELKEME, Viochalko’s research center.

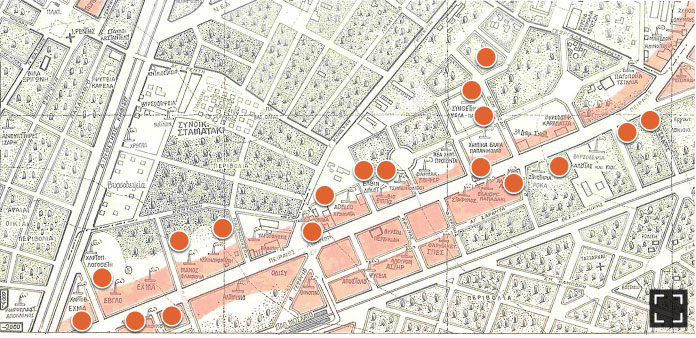

Dynamic map 4: Details on the key industries located on the fourth zone (Tavros to Moschato)

Source: K. Diamantopoulou, 1955

In Moschato, between the Strophi and the Cephissus, the Athens Vegetables Hall have oriented the local industries towards food and its related industries: oil mills (Oliva, Manos-Evglo, Minerva, Hydrogonisis), refrigeration (Olympos), flour mills (Astir). The distance from the center of Athens, the availability of land and the development of new technologies in the immediate post-war period, also favored the installation of a petroleum chemistry (Elbyn), paints and cosmetics (Adelco, Rolco Bianil, Giannidis-Vitex Group, Vechro Inks), plastics (Apco), paper-cardboard (EXMA, Logothetis), pharmaceuticals (EBIFER, SPES), textile establishments (Athinaika Striptiria Rokas bought by Biokarpet and Perfil Proussaloglou). Leather work remains an important activity there with tannery (Kaloutas, Perdikidi, Karapatsa and Simos), near the Cephissus.

The food industry continues to dominate today: meats (Floridis, Boudouris-Konsta and Bozionelos), packaging and printing companies (Tzimis printing and Koskinikis packaging). A mechanical industry remains, but specialized, such as Malidakis (laser cutting) and Polylift (elevators). We note Chrysafidis specialized in urban public networks and Krinos in the production of lime. Mass distribution is represented by Veroukas-Alpiko and Metro, as well as specialized distribution of textiles (Glou, Lito), glassware (Valavanis Glassworks exhibition center) and furniture (Entos, Sato, Spider). Among the services, we find the new headquarters of New Democracy, the IST school, and one of the 4 establishments of Teleperformance, in the industrial park of Athenarum.

Dynamic map 5: Details on the key industries located on the fifth zone (Tavros to Renti)

Source: K. Diamantopoulou, 1955

6th zone: In Piraeus, the Manchester of Greece…

From the end of the 19th century, the surroundings of Piraeus were home to the first Greek industrial revolution, with textile and chemical industries and flour milling, taking advantage of the facilities for importing raw materials. Around the 1950s, textiles were still very present with the hemp rope factory Mangou, Indiana, Gabriil (current Factory Outlet) and, in the area between the Karaiskakis stadium, the Elektriko, Sofianopoulos and Eponiton streets, the factories of Bambax, Bellis, Manousos, Aigio, Belka, Dimitriadis and the other installation of Gabriil-Chrysallis of which an element remains in front of the Neo Faliro station. On the other side of the Elektriko was one of the 4 Retsina factories and the Elpis spinning mill. The vocational SKYP school for textile workers is still visible. The chemical industry was represented by Chropei, Rolco Bianil (moved from Rentis), Dimitriadis (paints and detergents, naphtalene), and Sanitas (pharmaceuticals). There were many flour mills (Evtychia, Eurotas, Nikolettopoulos, Attikis), oil mills [7] (Elais, Elma Katsigeras), amylum factories (Biamyl, ZAAE, Azevap and Taygetos), Finopoulos Ivi and Barbaresos distilleries, the Keranis cigarette factory and in the Apollonos district, a wax factory, and the Greek Rice Mill. Packaging factories have logically set up, such as Vis, Papyros and Ermis. We also note the Keramikos porcelain factory, the ELSA tin factory, and the AHS electrical station.

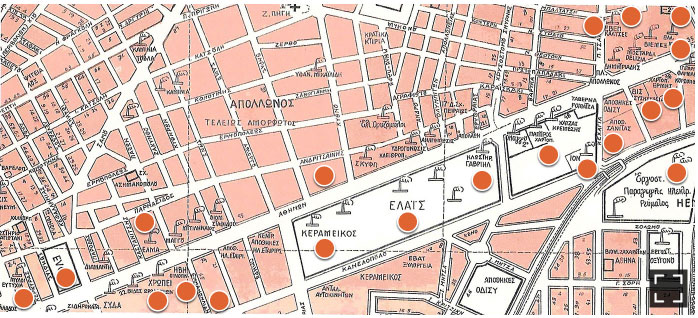

Dynamic map 6: Details on the key industries located on the sixth zone e expanding around Piraeus

Source: K. Diamantopoulou, 1955

The textile has completely disappeared, leaving ruins and wastelands. Only the Ion chocolate factory, the Elaïs oil mill and Dianik (meat) remain. In chemicals, we can mention the headquarters of Colgate and in Rentis behind Piraeus Street, Gabriil Group in cosmetics. The municipality of Piraeus has developed cultural services such as the Scholeion Theater of Irène Pappas and the Artspace Art Apollo, the vocational schools of Rallis, Skyp-IEK, Promitheus (mechanical and electrical) and Kesen (merchant marine) or administrative services such as Elstat. Large supermarkets have also found the vast land necessary: Leroy Merlin, Sklavenitis, Carrefour, Factory Outlet, Jumbo, JSK, Pet Services and the movement is intensifying with the construction of a commercial park by the Ten Brinkes group on the large land located between the Cephissus and the electrical plant.

Some general observations

We observe three “natural” phenomena following the economic occupation of the street: the specialized housing, for refugees and workers, which accompanies the economic development, the organization of economic activities by agglomeration and the continuous transformation of the industrial activity.

1st) A human geography in motion

The Piraeus Street is sparsely inhabited, apart from its first section, from Omonia to Gazi, and it has gone on for a long time: the aerial photos and the plans of Diamantopoulou confirm in 1955 the place of gardens and orchards. Industrialization and the “Asia Minor Catastrophe” led to the settlement of the area and the construction of housing. The occupation by the refugees from Asia Minor was first “wild”, but then organized with the construction of buildings whose apartments were distributed to them (“prosphygika”) [8]. The first were built in Tavros at numbers 200 and 211, and in St John Rentis, behind Piraeus Street, on either side of the Cephissus, then in Moschato and Neo Faliro. The current state of these dwellings is variable, but most often, if they are modest, they are quite pleasant, giving the impression of an “between self” adapted to the desires of their occupants, particularly in Rentis. Their occupants indeed, are also owners. The industrial development of the interwar period relied on this workforce. It accelerated after the Second World War, benefiting from the rural exodus, and was accompanied by the construction of worker’s housing.

If we keep the idea that economic growth generates a certain social and geographical distribution of populations, but that geographical stability can coincide with social evolutions, then we can undoubtedly say that the working-class neighborhoods of Petralona, Tavros, Moschato, Agios Ioannis Rentis and Apollona gradually gentrified, at the same time as the economic activity of their environment evolved. The hypothesis here is that the maintenance of a “soft” industrial activity (food or pharmaceutical-cosmetic industries) and the transition to a tertiary activity (services to industry, culture, public services, commercial surfaces, transport) have favored this social development. The crisis of the 2010s, by stopping housing construction, has however blocked geographical mobility.

On the other hand, more recently, immigrant populations have settled down in Tsaldari Street. The mediocre equipment of existing housing, the non-renewal of housing aggravated by the crisis and low rents, explain this influx. The process of gentrification has been blocked.

2nd) Certain economic activities agglomerate in certain places at certain times

Externalities linked to specialization (workforce, sub-contracting, access facilities for suppliers of the same product), added to externalities linked to location (Piraeus Street offers the advantages of a concentrated market and of traffic facilities) may explain agglomeration phenomenon [9].

The best known of these agglomerations are those of textiles and flour milling which characterized the port of Piraeus at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. They can be explained by the ease of access to raw materials and/or energy resources, linked to the opening of the Black Sea to Russian wheat or English coal.

Chemistry also required access to an economical source of energy. Polluting, it also had to stay away from homes. It found land in abundance between Tavros and Moschato. It included both the processing of food raw materials (amylum, glucose, oil) whose by-products are pasta, pastry, and soap, as well as purely industrial products such as resins, paints and varnishes, naphthalene, industrial naphtha-based oils, and pharmaceutical and cosmetic products.

The metal processing industries, also very polluting, have found the same land availability: at the beginning in Gazi, there are mechanical workshops of the same specialty, weighing equipment and foundries; later and lower, before the “Strophi”, “connected” to the SPAP line, several wire drawing or pipe factories processing copper, iron, and aluminum; today several distributors of kitchen equipment at the crossroads of Iera Odos.

Another agglomeration effect, that of food and leather industries, was linked to the presence of the Athens Vegetable Hall and the slaughterhouses. At the beginning, the tannery [10] followed the courses of Ilissos and Cephissus and the displacement of the slaughterhouses. After the bridge of Cephissus, three paper and cardboard packaging companies followed one another. Today, 350 establishments package and/or distribute various foodstuffs, meats, fruits and vegetables, oils. They call for the presence of refrigerated warehouses, packaging workshops (plastic films or barrels, wooden or cardboard boxes), printers, not to mention importers of machines intended for this branch.

3rd) The industrial landscape is transformed at the rate of a particularly active Schumpeterian process of “creative destruction”.

Destruction of the past

Vestiges of the past, these fallow lands, awaiting succession or re-use, or rising land prices. Vestiges still, these old buildings, abandoned to their fate, presenting an aesthetic interest (Sikiaridis, Nikolettopoulos, Finopoulos) or not (Spider, Biochalko). These industrial ruins form a desolate landscape. They anchored de-industrialization in people’s minds. And it is true that textiles, clothing, and tanning have been largely swept away by Asian competition, as often in Europe.

But this image must be nuanced: many of the companies that were once established on Piraeus Street are in fact still alive and prosperous. They only moved on Attica limits, to Inofyta, Schimatari on one side and Aghioi Theodori on the other. Thus Biochalko (metallurgy), Kalas (salt), Viosol (solar water heaters), Minerva, Vis (cardboard), Vitex, Chrotex and Vekro (paints). Mergers and takeovers have taken place in flour milling or metallurgy. These changes have been encouraged by the steady rise in land prices, by environmental concerns and by the measures instituted to promote the decentralization of activities.

And then, a few companies are still prospering on the site of their initial establishment: the Elaïs oil mill, the two chocolate factories Ion and Pavlidis, the pharmaceutical and cosmetic products Adelco and Koper. They have been modernized and extended. These are low-polluting industries close to their consumer market.

Creation of new activities

The transformation of Piraeus Street takes place also either through the renovation of industrial buildings, to which it gives an assignment that is most often cultural, or through the development of new industrial or tertiary activities.

Building renovation took many forms. The establishment was transformed into a museum (Fotoaerio, Mendis) or an educational establishment (the School of Fine Arts in Sikiaridis textile). The Poulopoulos hat industry has been restored by the Mélina Mercouri foundation, a fitness establishment has taken over the EBEM (metalworking) building, the Art Space Apollo has taken over the Greek rice mill building. Elaïs has restored the old Keramikos with its beautiful earthenware tiles. Sometimes the original building is replaced by a modern construction (Cacoyannis Foundation/Porphyra Dyeing, Center of the Hellenic World/Viosol), or integrated into new construction such as the Gavriil weaving factory in Factory Outlet. However, this already considerable work is far from complete.

The creation of new activities on the remains of old ones is another aspect of this process.

The new industries are mainly food, centered on Athens Vegetable Hall and taking advantage of the large Attica market. They consist, as we have seen, in the processing and packaging of meat and fruit and vegetables, in industrial bakeries, in catering. Their suppliers evolved at the same time, refrigeration, packaging, and a vigorous printing industry.

Mechanics, who has been, along with textiles, greatly affected by globalization, has seen the emergence of many highly specialized companies at the same time, such as Olympic Shoe engineering, Chrysaphidis, Vidoferro, Malidakis, Tzavidas, Polylift, Inox Mar, Afoi Simou.

Above all, Piraeus Street is a good example of the externalization of services to industry and thus it reflects the general evolution of economic structures: industrial research such as Elkeme, services to industry such as Cosmote, Vodaphone, RAE, Easy Mail, Teleperformance, CPI software. Otherwise, successful companies set up their exhibition and distribution center such as Kyriazis which builds solar parks in Alexandreia or Valavanis which manufactures bottles and glass objects in Larissa. Many distributors of machinery and equipment have also set up here, such as Rigas, industrial glues such as Bostik, printers such as AEG, pumps such as Marko and all kitchen equipment suppliers. Finally, nature abhors vacuum and open spaces have attracted corporate headquarters such as those of Colgate or the Hellenic Protein Group. Transport companies are multiplying near the port.

Conclusions

For a long time, the landscape of Piraeus Street marked the spirits. The “Manchester” of Greece [11] that was Piraeus, today resembles a field of archaeological ruins, whose chimneys are preserved like antique columns and whose ruins are restored.

But the image, as we have seen, is easy and misleading, and the reality more complex. Especially since a revival seems to be taking shape in recent years. Admittedly, the crisis has interrupted a lot of transformation/rehabilitation works and highlighted the massive overproduction of commercial buildings. And the public authorities, impoverished, had to limit their intervention.

But the Piraeus Street remains a major axis of the development of Athens and the transformation of its activities signals an adaptation of the industrial network rather than its disappearance and the evolution towards the tertiary sector that a large capital nourishes.

The development of several abandoned lands, the rehabilitation of several buildings, the astonishing case of Teleperformance and the installation of several companies mentioned above, are beginning to change the appearance of a space essential to the development of the city and which still offers many opportunities.

Acknowledgements

The Athens Social Atlas team, extends warm thanks to Konstantinos Lefakis for his valuable insights, as well as his technical support, in producing the Dynamic Maps that accompany this entry

[1] Sideris, Nicolas G. Η Ελληνική Βιομηχανία: βιομηχανική παραγωγή και αξία αυτής: κατά τα έτη 1945 – 1946 – 1947 εν συγκρίσει προς το έτος 1939, Αθήνα 1948. (The Greek Industry: industrial production of the years 1945-1946-1947 compared to the year 1939) Athens 1948.

[2] Kiki Diamantopoulou probably drew up in 1955 a series of maps of Attica at the 5000th, in which she noted the industrial establishments. They are archived at the Istoriko Archeio tou Dimou Athinaion (Himiktimatologikos Chartis tou Lekanopediou Attikis).

[3] Formerly ΗΣΑΠ Ηλεκτρικοι Σιδηροδρομοι Αθηνων Πειραιως for the first (stations of Monastiraki, Thisio, Petralona, Tauros, Kallithea, Moschato, Neo Faliro and Piraias) and ΣΠΑΠ Σιδηροδρομοι Πειραιως Αθηνων Πελοποννησου for the second (Stations of Larissa, Rouf, Tauros, Lefka and Peiraias and marshalling stations of Larissa-Peloponnisus, Tavros and Rentis)

[5] Ministerial Ordre ΥΑ 7863/1383/30-1-1997 – ΦΕΚ 267/Δ/7-4-1997

[6] So called because of the Durruti silk factory, created in 1834, which today houses the Pinacoteca of Athens. See Agriantoni, Christina: “The Metaxourgeio district”, in Agriantoni, Christina – Maria-Christina Hadziioannou « Το Μεταξουργείο της Αθήνας », Center of Neohellenic Research, Αθήνα, 1995. In 1930, the author listed 257 “heavy” (metalworking, woodworking, graphic arts) and “light” (shoes, furniture, bakery, garages, textiles) industry workshops, more than half of which were concentrated between Kolonou and Salaminos streets, perpendicular to that of Piraeus.

[7] The oil mills are classified in chemistry by Elstat until the 1960s.

[8] The presentation by Elisa Papadopoulou and Georges Sarigiannis on the prosfygika in the plain of Athens (EMP 2006) is a valuable inventory of the installations. They thus cite at Tavros the Ano Nea Sphagia, Germanika and Panagitsa ensembles, at Moschato the ensembles below Minerva and on the other side of the Elektriko, between the Cephissus and Constantinopoleos Street and at Saint Jean Rentis between Kanari and Metamorphoseos streets, the Apollonas district, the Polykatoikies Fleming and the Stamataki, in Neo Faliro the complexes located between Eponiton and Katsoulakou, Kanellopoulou and Smyrnis streets.

[9] We refer for the theoretical aspects to Alfred Marshall (Principles of political economy, 1890), Giacomo Beccatini (industrial districts and 3rd Italy), Alain Lipietz, JF Eck and Michel Lescure (Towns and industrial districts in Western Europe 17-20th centuries)

[10] In “The end of Giants” (Το Τέλος των Γιγάντων), a study on tanning industry notes 17 companies in Renti, 10 in Tavros, 2 in Moschato, 4 in Kaminia.

[11] Tsokopoulos, Vasias : « Pireus 1835 1870. Introduction to the history of the Greek Manchester », Editions Kastaniotis, Athènes 1984. (Τσοκόπουλος, Βάσιας, Πειραιάς 1835-1870. Εισαγωγή στην ιστορία του ελληνικού Μάντσεστερ).

Entry citation

Bournova, E., Gouzi, V. (2023) Going down Piraeus Street: the metamorphoses of a street, witness of industrial Greece, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/piraeus-street-witness-of-industrial-greece/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.112

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9