2016 | Dec

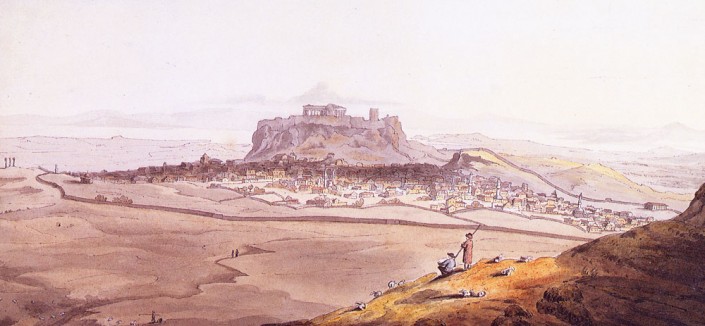

The end of the Revolutionary War found Athens heavily wounded, having suffered severe damages. Yet, although the Turkish guard definitively left Acropolis only in March 1833, the gradual regeneration of the city had begun as early as 1830.

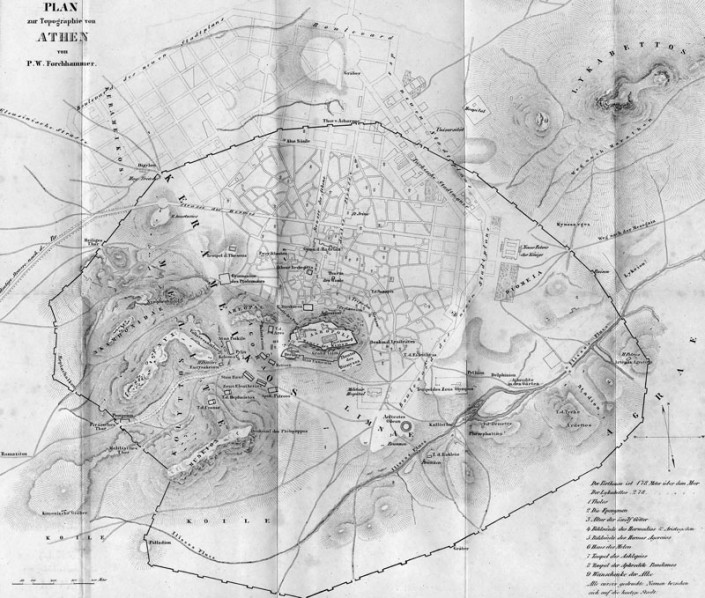

In November of 1831, the architects Stamatis Kleanthis and Eduard Schaubert, students of perhaps the most important German neo-classical architect, Karl Friedrich Schinkel, settled in Athens, where they carried out a systematic topographical survey and subsequently drafted a city planning proposal, in anticipation of Athens’ possible establishment as the capital of the newly-formed statenewly-formed state. In fact, in May 1832, the post-Kapodistrian Provisional Government tasked them with elaborating a New Plan for the City of the Athens, which was approved in July 1833 by the Regency, who had in the meantime take the reins of state.

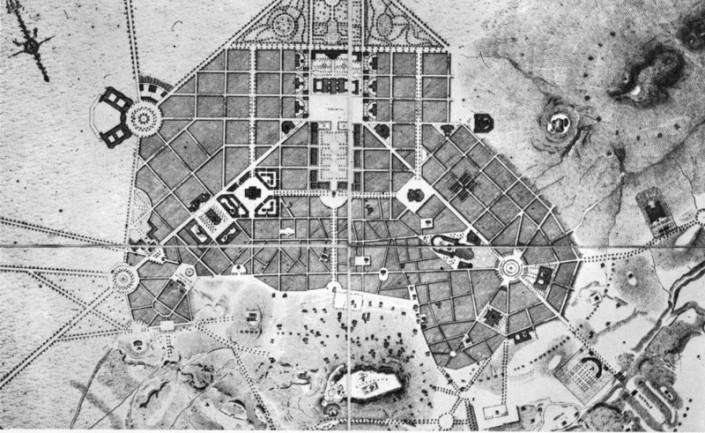

Let us see, roughly speaking, what that original plan anticipated. The New City included about half of the Old one, while extending from it to the West, the North and the East. The other half of the Old City, defined by Hephaestus, Pandrosou and Adrianou Sts., was to be expropriated for archeological excavation. But even the preserved section of the Old City was maintained only as a geographical zone, and not as an already constructed space, since it was anticipated that its largest part would be divided up by new roads and standard rectangular blocks. The main axes would form an isosceles triangle, with its peak at today’s Omonia Square, its sides defined by Piraeus and Stadiou streets, and Ermou Street as its base. Its entire orientation was aimed at Piraeus, the Stadium and, primarily, the Akropolis, at whose feet it spread out in an open embrace. The Royal Palace was expected to stand at the peak of the triangle: a symbolic merger of the geometric apex and the apex of state power. The orientation of the sides of the triangle was not accidental: As Kleanthis and Schaubert note in their memorandum, “they meet in such a manner that allows viewing simultaneously the comely Lykavitos, the Panathenaic Stadium, the rich-in-proud-memories Akropolis, and the military and commercial ships of Piraeus, from the balcony of the Royal Palace”. Piraeus and Stadiou streets were interrupted, symmetrically in relation to the Royal Palace, by the Borsa (Stock Exchange) and Theatrou squares. These are today’s Koumoundourou and Klafthmonos Squares which, in fact, are symmetrical, something which one cannot easily recognize within the present-day chaos of Athens.

The road network was elaborated in part as spokes with hubs at circular plazas, and in part as horizontals and verticals in the direction of the main axes, always with absolute regularity. The broader area of the Royal Palace was surrounded by wide avenues, which we will discuss more fully later. The exact sites of all the public buildings and, more generally, the districts for all of the functions of the City: Ministries, Courts, Military Barracks, Police, the Postal Service, the Mint, Cathedral, Parks and so forth. The totality was designed to host all of the activities of a capital and a population which was expected to reach around 40,000.

The geometric planning that runs through both the Kleanthis-Schaubert plan and the Klenze plan (which we will turn to soon) is a basic constitutive element of the neoclassical-romantic city planning as it had taken shape by the end of the 18th century, characterized also by the functional planning and the rational use of space, a perception seamlessly connected with the new bourgeois consciousness, finding its symbolic expression in the Burg, the New City.

By the end of the year 1833, the implementation of the plan had begun. But once it was realized the extent of the areas to be expropriated for the erection of public buildings, the development of the parks and the roadway network, as well as the archeological excavations, a wave of protests erupted, leading the Regency to order a cessation in the implementation of the plan, in June 11, 1834.

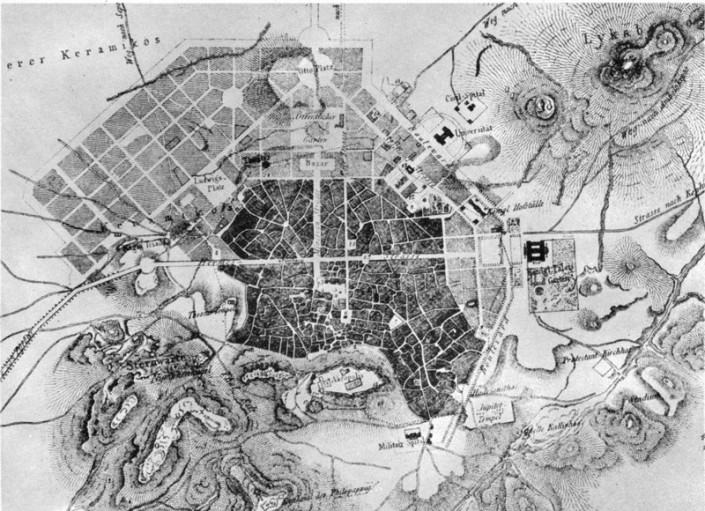

Next, the famous Bavarian architect Leo von Klenze was summoned, who drafted in September 1834 a revision of the original plan. Its main characteristics were a reduction in the total size of the city and of the excavation area; a reduction in the width of the roads and the spatial surface of the plazas, as well as the elimination of avenues within the city and a reduction of the parceling out of the Old City; and finally, the movement of the Royal Palace, and thus of the city’s entire administrative center of gravity, from Omonia Square to the upper reaches of Keramikos.

Klenze’s amendments confined the difficulties, without, however, eliminating them. The start of demolition in order to open, initially, the new strrets of Aiolou, Ermou and Athinas, met the opposition of residents, to whom the government had not provided new plots of land, as had been agreed to. Faced with the inability to financially support the projected expropriations, a further reduction in the archeological area was decided in 1836, known as the Hansen-Schaubert revision. Other revisions, on a smaller scale, took place throughout the 19th Century.

Meanwhile, the issue of the Royal Palace remained pending. Finally, the respected Bavarian architect Friedrich von Gaertner was called in, who decided to choose the defile running between Lykabettos and the Akropolis, outside of the wall of the Mesogaia Gate, and worked out plans for the construction of the Royal Palace where it was finally built (today’s Parliament building). A few changes of layout in the area of the Royal Palace were made also in 1837, with the so-called Hoch plan.

The practical effect of these successive changes was, on the one hand, the preservation of a large section of the Old City, with a corresponding delay in the anticipated extension of the Capital towards its new borders, and on the other hand, a reorientation of the City towards the final building site of the Royal Palace, with the valorization of the section east of the Athinas street axis. This valorization is manifest, for instance, in the disproportionate development of Stadiou, and later of Panepistimou, streets in comparison to Piraeus street, of Klafthmonos Square compared to Koumoundourou Square, and so on.

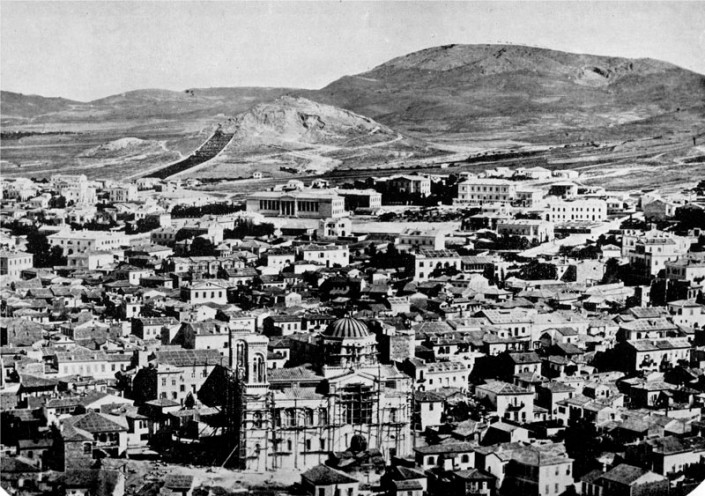

Athens was late in expanding into the entire space that the plans provided for. For decades, in fact, its limits remained essentially those of the Old City. It is interesting to note that the areas which are today the center of the city, such as Omonia and the whole northern section of Piraeus street, remained nearly deserted until 1870-1880, while the Petrakis Monastery, which today lies in Kolonaki, was still in 1880 a rural monastery. The area of Strefi remained, until nearly the beginning of the 20th century, the boundary of the City, Alexandras Avenue was an uninhabited ravine between the Tourkovounia and Lykabettos, and Kypseli had a handful of remote farmhouses and a few cottages, where Athenians were going for an outing.

This development is connected to the issue of Athens’ population growth rate. Its establishment as capital understandably instigated a large inflow of new residents. From roughly 12,000 in 1834, the number of residents doubled over the next decade. Still, the expectation of Kleanthis-Schaubert of 40,000 inhabitants did not materialize before the decade of 1860, and the milestone of 100,000 was not passed until the end of the 1880s. We will not get into the causes of this growth rate, which in any case has to do with the long-term activity of the city as, mainly an administrative rather than an industrial center; the latter role was adopted by another neighboring city: Piraeus.

Entry citation

Kallivretakis, L. (2016) Planning Athens in the 19th Century, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/planning-19th-century/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.65

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Καλλιβρετάκης Λ (1996) Η Αθήνα τον 19ο αιώνα: Από επαρχιακή πόλη της Οθωμανικής Αυτοκρατορίας, πρωτεύουσα του Ελληνικού Βασιλείου. Στο: Μοσχονάς Ν (επιμ.), Αρχαιολογία της πόλης των Αθηνών: επιστημονικές-επιμορφωτικές διαλέξεις, Αθήνα: Αρχαιολογία της Πόλης των Αθηνών, σσ 173–196. Available from: http://helios-eie.ekt.gr/EIE/handle/10442/7282.

- Μπίρης Κ (1966) Aι Αθήναι από του 19ου εις τον 20ον αιώνα. Αθήνα: Έκδοσις του Καθιδρύματος Πολεοδομίας και Ιστορίας των Αθηνών.

- Μπίρης Κ (1933) Τα πρώτα σχέδια των Αθηνών. Ιστορία και ανάλυσίς των. Αθήνα: Τύποις Κ. Σ. Παπαδογιάννη.

- Πολίτης Α (1933) Ρομαντικά χρόνια. Ιδεολογίες και νοοτροπίες στην Ελλάδα του 1830-1880. Αθήνα: Ε.Μ.Ν.Ε. – ΜΝΗΜΩΝ.

- Τραυλός Ι (1960) Πολεοδομική εξέλιξις των Αθηνών. 2ο έκδ. Αθήνα: ΚΑΠΟΝ.

- Matton L and Matton R (1963) Athènes et ses monuments: du XVIIIe siècle à nos jours. Athens: Institut français d’Athènes.