The social space of private education in Athens

2015 | Dec

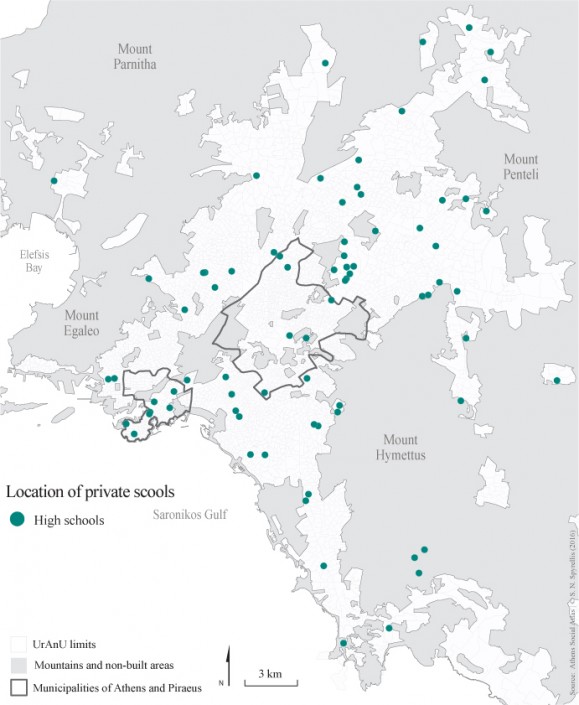

The majority of families in almost every OECD country choose public primary and secondary education for their children. With the exception of some countries such as Australia, Mexico and Chile, where families contribute extensively in private education, primarily in the form of tuitions, such expenses in other countries do not exceed 10% (OECD 2013). In Greece, following the crisis, there is a drop in the number of students in private schools, with enrolments at around 6%. This percentage is relatively higher in primary education, especially kindergarten, and gradually decreases in secondary education (ΕΛΣΤΑΤ 2012). These numbers represent the current state of private education in Athens and the wider Metropolitan Area of the Capital, as this sector features a concentration in the large urban centres of the country, with approximately 80% of private schools located in Athens and Thessaloniki. Actually, over 50% of the total student population of private schools and of such school units is currently concentrated in Attica (Υπουργείο Παιδείας και Θρησκευμάτων 2012).

Despite the relatively small size of the Greek entire education system, private education is a privileged area where one can study the social formation of educational strategies during the post-dictatorial period, as these are reflected and implemented in the choice of school. Although empirical data on private education in Greece are limited, we can see that some parts thereof function as social mediators for the social reproduction of processes of upper and middle class groups (and for the social mobility of lower class groups). The emergence of private education as a social space, according to Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of field (1995) allows a privileged sociological insight into the variations and hierarchies prevailing in private institutions, with a primary distinction between public and private education.

Thus, focusing on secondary education, we note that the families who choose to educate their children in private educational institutions are significantly different from those following the public system, as they usually possess a privileged position in society and a significant accumulation of different capital forms (both economic and cultural). These are families where parents are, primarily, freelancers, pursuing scientific and administration professions, with a high educational level, high income, sometimes with great wealth (e.g. real estate, stocks, bonds), which consume a significant portion of their income for cultural goods (e.g. cinema, theatre, museums and books) (Valassi 2009).

Apart from the divide between private and public schools, there is also a divide separating the elite private schools from the other private (and, of course, public) schools, thus establishing a clear social boundary. In these schools, there is an over-representation of the higher professional categories with a relatively small specific weight in the economically active population of Athens, such as self employed professionals (architects, engineers, lawyers, doctors), industrialists and entrepreneurs, senior public and private sector executives, academics and politicians. This goes parallel to the extremely high percentage of parents with a very high educational capital (the percentage of university graduates reaches 80%) (Βαλάση 2012).

Studying the socio-economic features of families whose children study in such private schools helps us see the social advantage of these families and the educational and social networks in which they belong, which ensure social reproduction through continuous social interaction among peers, and entails to some extent spatial proximity. An interesting aspect is the residential area as a sign of social status, which also provides indirect information on the income and lifestyle of these families. Thus, 51% of the families of children studying in elite private schools in Athens reside in areas traditionally hosting upper and middle classes, such as Paleo Psychiko, Filothei, Kolonaki, Ekali, Kifissia, Voula – Vouliagmeni, Maroussi, while 8% of these students reside in suburbs of the new middle class (Pallini, Gerakas, Koropi) (Βαλάση 2012).

Figure 1: Residence of families of elite private school students

Source: Valassi (Βαλάση 2012, 115); more details on the typology used, in Maloutas (2007).

Within the area of elite private education, we observe one more distinction: one between aristocratic schools and the less popular and selective ones (Βαλάση 2012), the first ones being known for the strategic inculcation of an international culture in their students (Βαλάση 2012). This process is accomplished through a series of school activities with international orientation and the cultural identity of each of these schools (Catholic French schools, schools with roots in the American missionary movement in the Near and Middle East, German schools etc.). All these schools have a long and important history and tradition in Greece.

In the last twenty years, an important development launched a further distinction within the elite private school system and institutionalised the process of integrating students into the European and international environment at a higher level. This change was the integration of international educational programs, such as the International Baccalaureate (IB) (Βαλάση 2008). The IB is a high school diploma allowing admission to higher education and is essentially a decentralised educational program, in the sense that it does not belong to a state or international organisation, but to a non-profit organisation – the International Baccalaureate Organisation (IB). Its curriculum and educational content is the same in every country, and English is the main teaching language (followed by Spanish). Today, 13 schools in Athens (and Thessaloniki) offer the International Baccalaureate, enabling graduates to enter universities abroad, mainly in England and the USA, depending on their scores. In 1984, the Moraitis School was the first private school to offer Greek students the choice to attend the International Baccalaureate. According to I.B.O. data, a decade earlier, in 1976, the American Community School (ACS) was the first international school in Greece to become a member of the “IB World Schools” community offering the IB option.

Privileging students, both through their families and through the elite private schools, with a kind of international capital and a cosmopolitan osmosis is, along with studies abroad (Panayotopoulos 1998), a dominant strategy of the upper social classes of Athens, and one of the privileged ways to access the field of power in Greece (Panayotopoulos 2000) while ensuring, at the same time, the future participation of students to a globalised educational and professional market.

Entry citation

Valassi, D. (2015) The social space of private education in Athens, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/private-education/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.18

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Βαλάση Δ (2008) Διεθνοποίηση ή/και παγκοσμιοποίηση στην εκπαίδευση: η περίπτωση του International Baccalaureate. Επιστήμη και Κοινωνία 19: 335–365. Available from: http://ejournals.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/sas/article/viewFile/675/673.

- Βαλάση Δ (2012) Προνομιακή μάθηση ή εκμάθηση του προνομίου: ο κοινωνικός χώρος της ελίτ δευτεροβάθμιας ιδιωτικής εκπαίδευσης στην Ελλάδα. Παναγιωτόπουλος Ν (επιμ.), Κοινωνικές Επιστήμες. Ετήσια Τρίγλωσση Επιθεώρηση Κοινωνικών Ερευνών, Αθήνα: Εθνικό Κέντρο Κοινωνικών Ερευνών 1: 95–123.

- ΕΛΣΤΑΤ (2012) Στατιστικά Θέματα: Εκπαίδευση, Πρωτοβάθμιας και Δευτεροβάθμια Εκπαίδευση, σχολικά έτη 2010 – 2011 & 2011 – 2012. Αθήνα.

- Υπουργείο Παιδείας και Θρησκευμάτων (2012) Πίνακες Ιδιωτικών Σχολείων. Αθήνα. Available from: http://www.minedu.gov.gr/idiwtikh-ekpaideysh/idiwtika-sxoleia.

- Bourdieu P (1992) Μικρόκοσμοι: Τρεις μελέτες πεδίου. 1st ed. Παναγιωτόπουλος Ν (ed.), Αθήνα: Δελφίνι.

- Maloutas T (2007) Middle class education strategies and residential segregation in Athens. Journal of Education Policy 22(1): 49–68. Available from: http://www.informaworld.com/openurl?genre=article&doi=10.1080/02680930601065742&magic=crossref||D404A21C5BB053405B1A640AFFD44AE3.

- OECD (2013) Education at a Glance 2013. OECD Publishing. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/edu/eag2013 (eng)–FINAL 20 June 2013.pdf.

- Panayotopoulos N (1998) Les grandes écoles d’un petit pays: Les études à l’étranger: le cas de la Grèce. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, Seuil 121–122: 77–91.

- Panayotopoulos N (2000) Une école pour les citoyens grecs du monde: les enjeux nationaux de l` international. Regards sociologiques 19: 29–55.

- Valassi D (2014) Elite Private Secondary Education in Greece: Class Strategies and Educational Advantages. Culture & Education 92(6): 22–41.

- Valassi D (2009) Choosing a private school in the Greek education market: a multidimensional procedure. In: International Seminar: Education Market, Geneva.