Residential Segregation, Education and the City: Educational Strategies of Middle Class Groups in West Attica

Vergou Pinelopi

Education, Quartiers, Social Structure

2017 | Jul

School segregation results from the unequal distribution of social and ethnic or minority groups at different schools, compared to their average in the population of a specific area. This distribution results in the concentration of certain groups in some schools and their underrepresentation in others (Massey and Denton, 1993: 283). Urban and school segregation are two different topics related to the analysis of residential space and education. However, they are connected through the spatial distribution of schools in urban space and the ways their enrolment is controlled by different systems of school catchment areas. School segregation reflects local inequalities in terms of accessing particular educational resources, which create social and spatial boundaries between schools and urban areas, and often lead to the marginalization of socially vulnerable groups.

It is crucial to consider the role of the middle classes and their choices in education services as a key mechanism in the production of new forms of segregation and fragmentation of urban space. Upper and middle social classes adapt strategies of distance or proximity with other social groups in order to select and control the nature and intensity of their social interactions. Strategies of “secession”, “colonization” or “partial exit” (Atkinson 2006, Andreotti et al. 2012) affect their coexistence or separation from other social groups and intensify their educational selectivity in the school system. Positive neighborhood effects and socialization with like-minded individuals -“people like us”- are important factors for school choice by middle class parents.

Education plays an important role in social mobility, since it affects the preservation/improvement of social status by providing access to better occupational and social positions. Through a closer examination of different forms of educational strategies of middle class groups in a suburb of Athens, we analyze the social-spatial disparities which are enhanced through middle classes school choice; we also analyze how the school system reproduces social segregation and acts highly selectively against socially disadvantaged groups.

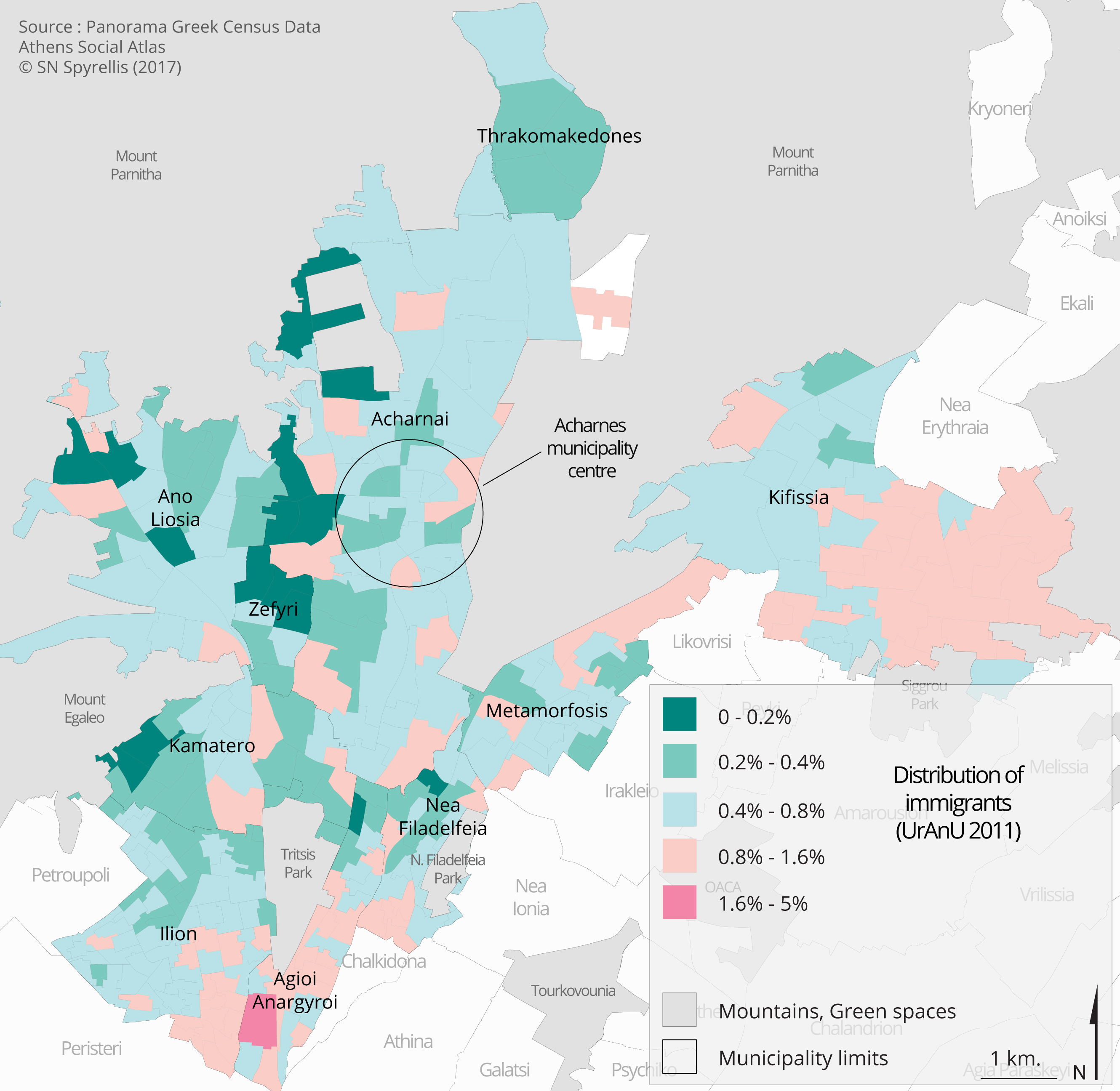

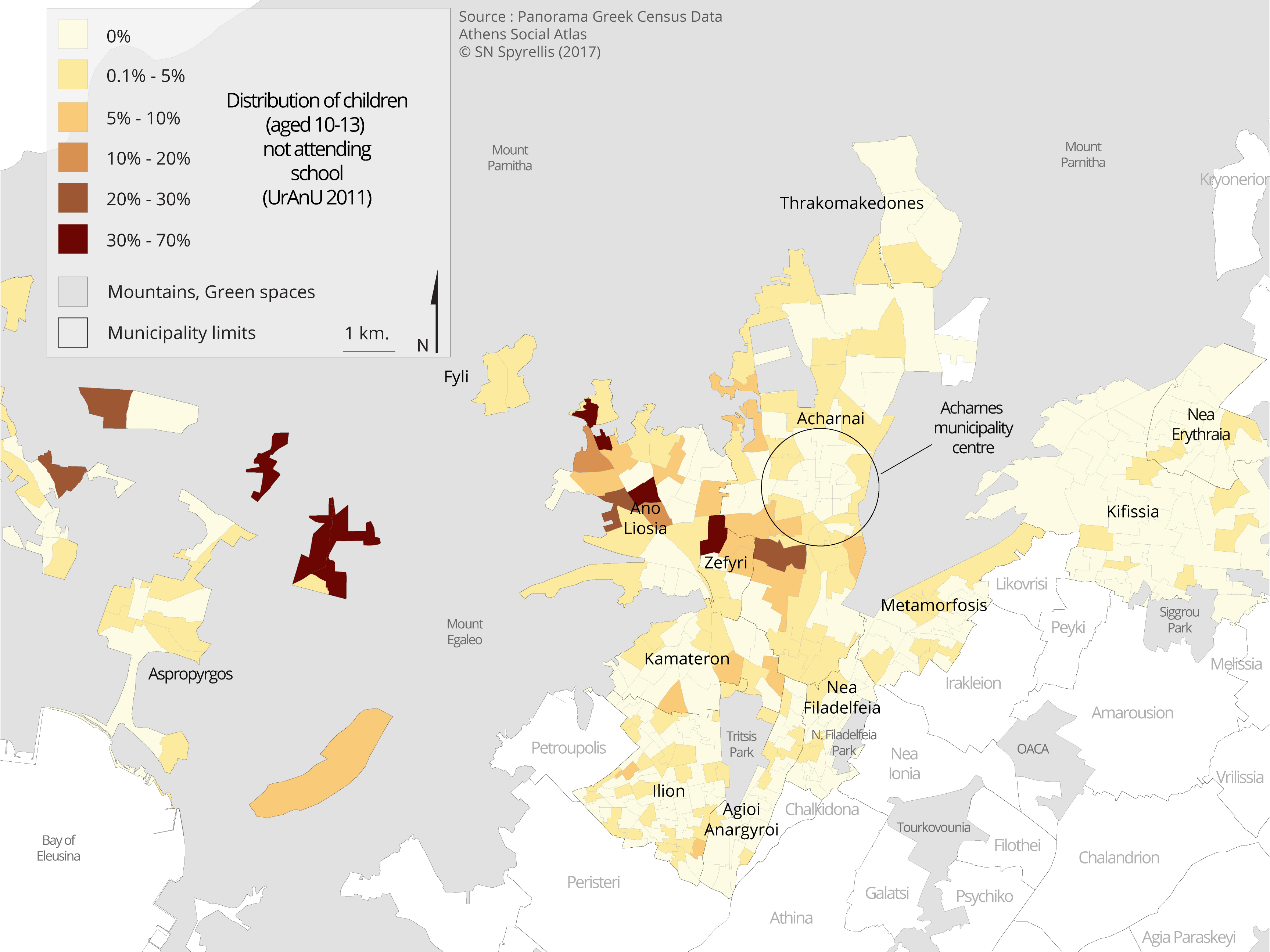

In Greece eenrolment is controlled by catchment areas and, therefore, the pupil population reflects the social profile of their neighbourhood (Μαλούτας 2006). The research area (Municipality of Acharnes) is characterized by heterogeneity, with an important mix of social strata and ethnic groups involving a broad range of ethnic and cultural identities (Roma people, Greek origin groups repatriated from the former Soviet Union and Albania, immigrants from different Balkan countries, Asia and the former Soviet Union) (Map 1). This diversity of social profiles and ethnic origins is related to diversified educational outcomes and to the educational strategies developed by middle class families.

Map 1: Distribution of immigrants in Acharnes and the neighbouring Municipalities of Ano Liosia, Zefyri, Kamatero, Ilion, Aghioi Anargyroi, Nea Filadelfeia, Metamorfosi, Thrakomakedones, Kifissia [1]

Data source: Panorama of Greek Census Data 1991-2011 (https://panorama.statistics.gr/)

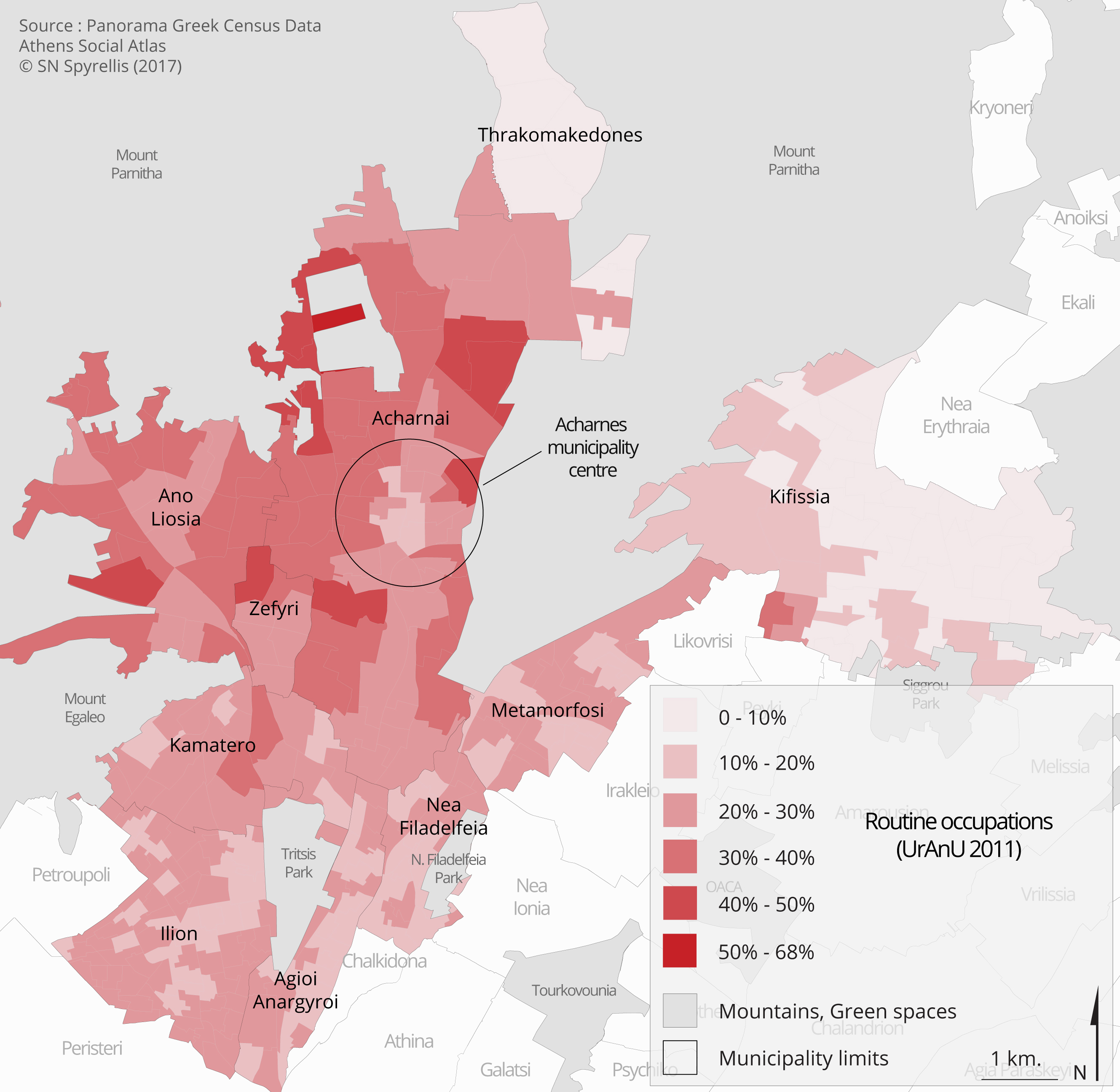

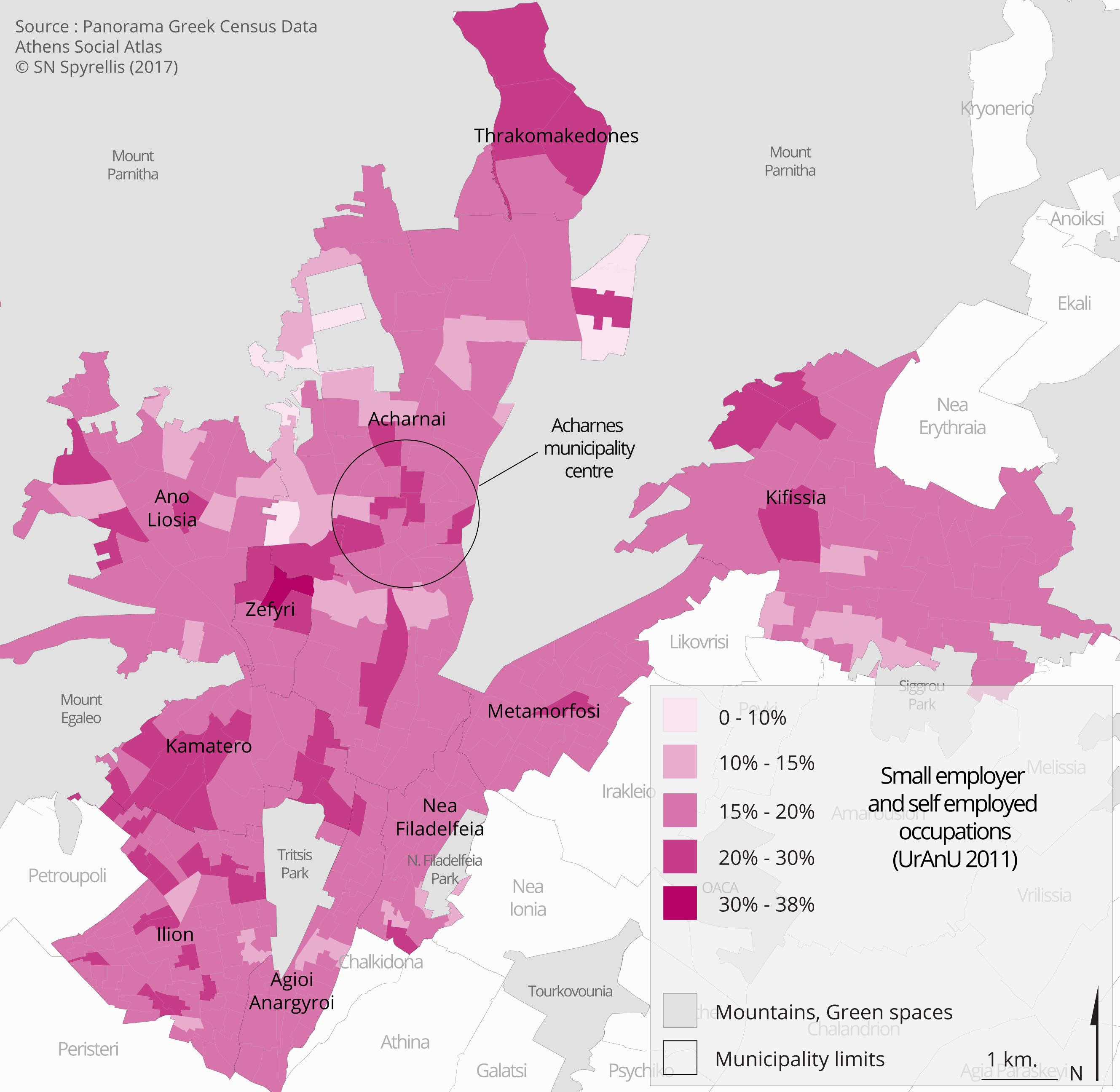

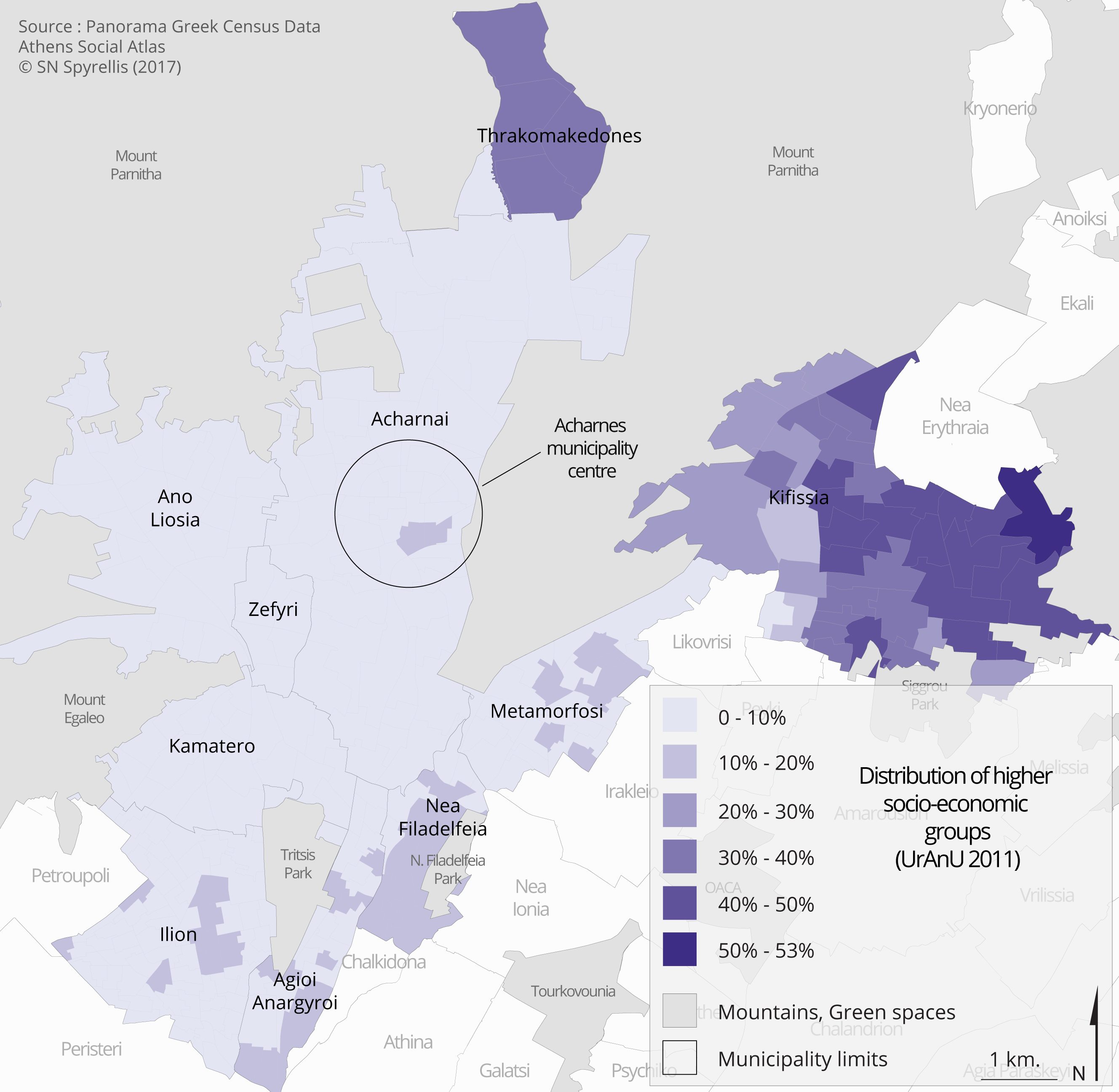

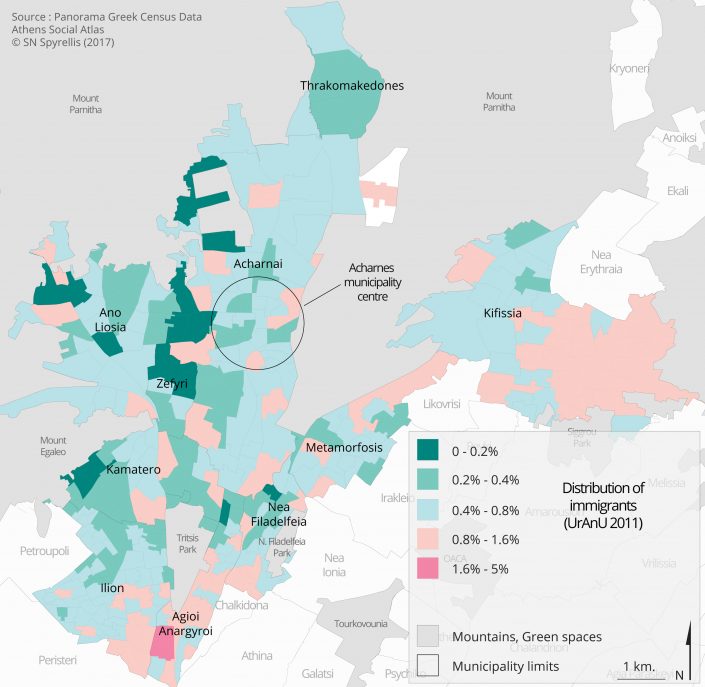

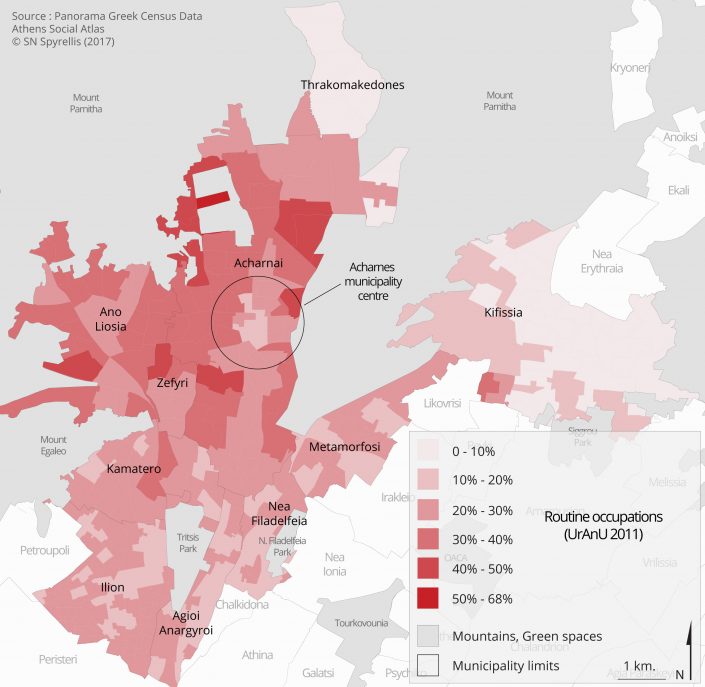

Our research data (grades, drop-out rates etc.) were mainly collected from four (4) secondary schools in the Municipality of Acharnes-Menidi (north-western suburbs of Athens). 55 semi-structured in-depth interviews with parents, teachers and key stake holders in secondary school education provided further data and insight. The application Panorama of Greek Census Data 1991-2011 (ΕΛΣΤΑΤ-ΕΚΚΕ, 2015) was also used to obtain information on the social-economic profile of neighbourhoods at the census tract level. The socio-economic profile of households was based on broad occupational categories (Maps 2, 3, 4).

Map 2: Distribution of lower socio-economic groups (routine occupation: cleaners, un-skilled workers, etc.) in Acharnes and the neighbouring Municipalities of Ano Liosia, Zefyri, Kamatero, Ilion, Aghioi Anargyroi, Nea Filadelfeia, Metamorfosi, Thrakomakedones, Kifissia

Data source: Panorama of Greek Census Data 1991-2011 (https://panorama.statistics.gr/)

Map 3: Distribution of self-employed occupations and small entrepreneurs in Acharnes and neighbouring Municipalities of Ano Liosia, Zefyri, Kamatero, Ilion, Aghioi Anargyroi, Nea Filadelfeia, Metamorfosi, Thrakomakedones, Kifissia

Data source: Panorama of Greek Census Data 1991-2011 (https://panorama.statistics.gr/)

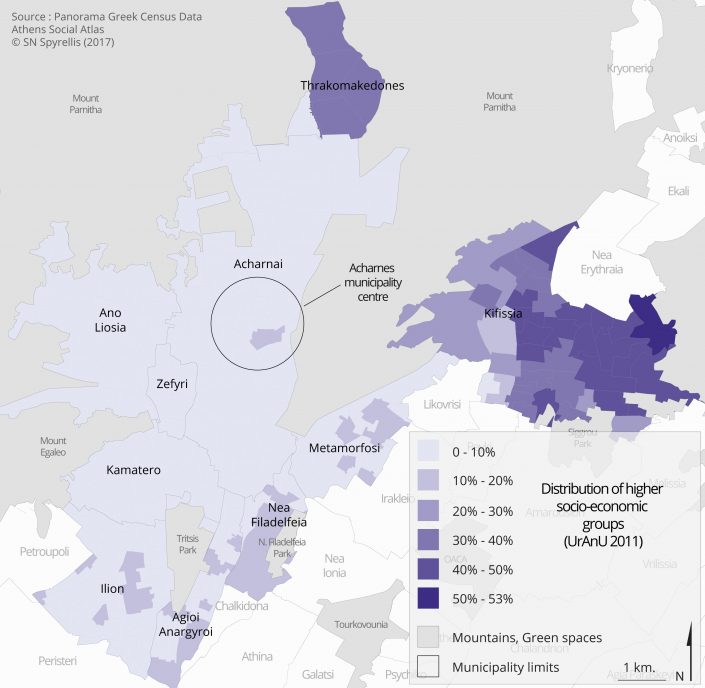

Map 4: Distribution of higher socio-economic groups and higher administration staff in Acharnes and neighbouring Municipalities of Ano Liosia, Zefyri, Kamatero, Ilion, Aghioi Anargyroi, Nea Filadelfeia, Metamorfosi, Thrakomakedones, Kifissia

Data source: Panorama of Greek Census Data 1991-2011 (https://panorama.statistics.gr/)

Educational strategies of middle class parents and the avoidance of local schools

Understanding socio spatial changes in cities means to understand the socio-spatial relations that are formed affected by the strategies of upper and middle social groups. It is crucial to consider their their choices in education services as a key mechanism in the production of new forms of segregation and the fragmentation of urban space.

According to our research findings -corroborated by similar findings in other cities- we conclude that there are different categories of parents who either choose or avoid local schools (public or private):

- Parents from upper and middle social groups (executives, directors in private companies, doctors, lawyers etc.) often choose to send their children to private schools outside their residential area. There was a significant increase in the proportion of children who enrolled in private schools (accessed through private school bus systems) until the mid 2000s.

- Parents from lower middle classes (intermediate occupations, like employees in private or public services and technicians) often send their children to a different public school outside their residential area, through the use of a false address (e.g. the address of a relative or friend living near the targeted school).

- Competition between schools, and intervention strategies of middle class parents, is more intense when the presence of diverse minority or ethnic groups is more visible (Muslims, Roma). Some middle class parents choose to send their children to the school of their residential area either because they have strong ties with the area or because they cannot afford a private school. These parents adopt intervention strategies though various social networks (family and friendship ties, political associations etc.) and/or through education specific networks (like parents associations) in order to monitor the educational attainment of their children and control their contact with children from different groups. They often co-operate with the school administration in a clientistic way: they ‘buy’ preferential treatment for their children by offering services to the school (economic support, assistance in specific needs, etc.); they influence the delimitation of school catchment areas by influencing decisions of local authorities (mainly near Roma settlements).

- Parents from lower social groups are constrained by their limited means and often seem less interested in their children’s educational trajectories. They have to adjust to the specific educational environment their children are officially assigned to, with its specific social and economic characteristics, and they often try to adopt middle class educational strategies where possible. Working class parents also perceive the presence of immigrants, Roma or Greeks from the former Soviet Union, as negative for their children’s school progress. We observed that they adopt the same strategies as middle class parents: geographical distance and attendance in schools far from the residential area of groups to avoid or by adopting the symbolic distance between “us” and “them”.

Different factors affect the school choice of middle class parents:

- School pupil composition and the strong presence of ‘unwanted’ social and ethnic groups are the main reason for local school avoidance. The social heterogeneity of the neighbourhood is a factor for school avoidance, particularly when there are deprived areas near the schools. School avoidance strategies start being deployed from elementary education and are further developed and intensified in secondary education.

- Personal networks influence the access of social groups to education and help middle class parents to find ‘good’ schools and to achieve transfers from one public school to another. These parents have strong bonds with the school administration and try to develop common attitudes and behaviour with people they feel sharing social norms and habits.

- Language is a key item for manipulating social information and for social networking. It also defines the acceptance or not of the different ethnic groups in school. According to parents’ responses, all pupils have the right to education regardless of their social or ethnic background. However, they believe that pupils without language proficiency are a threat to the school’s performance, and consequently to the performance of their children. In some cases of highly diverse neighbourhoods, parents complained about teachers who give special attention to immigrant and Roma pupils, and less to their own children.

The reputation of schools is very important in the process of attracting pupils from upper and middle class groups. The attraction of pupils with higher economic and social status preserves the school’s reputation, its image and the support of local elites. In order to attract pupils from the upper and middle classes, schools adopt strategies of academic selection, such as high grades and flexible administrative procedures for transfers to other schools. They also use tactics like suspension of pupils with deviant behaviour, indirect intervention for transferring problematic pupils, usually from disadvantaged social groups, to other public schools.

We conclude that school choice is directly and dynamically connected to class differences and is also a factor that affects and maintains segregation in the neighborhood. For middle class groups, the choice of school depends not only on ethnic school composition, but much more on socio-economic characteristics and the social homogeneity of the pupils. They believe that the presence of working class children and immigrants downgrades the level of the school as they are a “wrong role model”.

Ethno-cultural diversity and social segregation

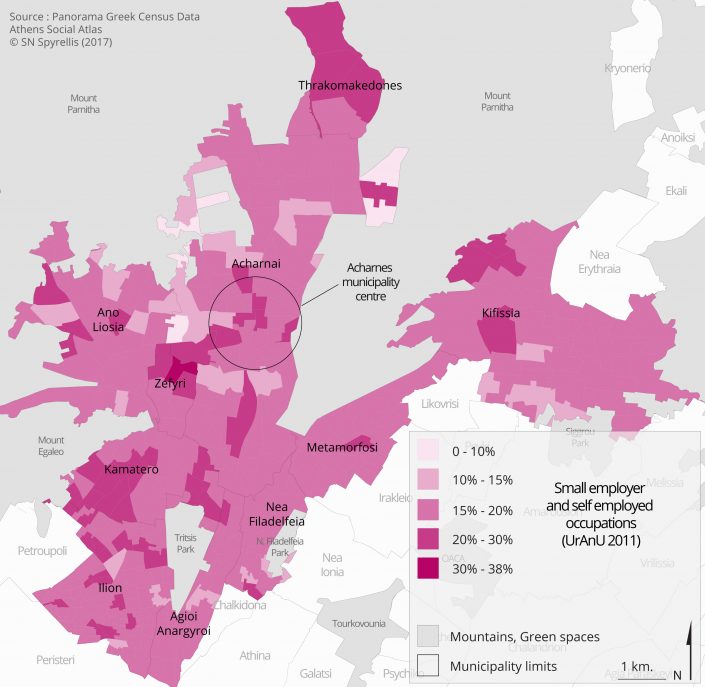

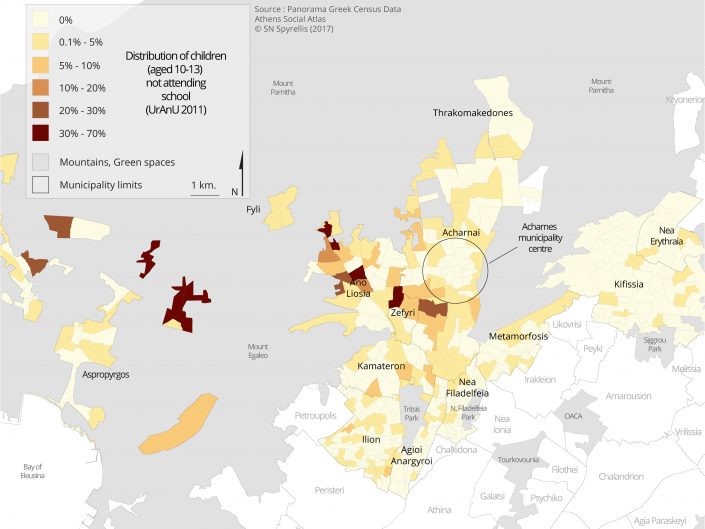

There are different middle class educational strategies that intensify social selectivity. These strategies of middle class parents affect the make-up of the school, strengthen social segregation among schools and residential areas and stigmatize neighborhoods. The early stage of elementary education is the starting point for choosing school, and middle class parents tend to search for the best schools since the beginning. The presence of Roma pupils is a criterion for school avoidance, which intensifies segregated in education and in residential areas. The making of a new school near a Roma settlements with homogeneous composition (exclusively Roma children) is an indication of social segregation, exclusion and ghettoization. Similar tactics are found in the neighbouring municipality of Zefyri with the same social-ethnic composition of the population. In West Attica there is a significant dropout rate. Map 5 shows all persons aged between 10 and 13 that were not involved in any kind of education in Acharnes-Menidi and the neighbouring suburbs. This group becomes increasingly marginal -since the general tendency is for most young people to have at least 12 years of education- and has a very clear social and spatial delimitation. Its members are concentrated in the deprived neighbourhoods where there is a strong presence of disadvantaged groups, especially Roma. Dropout rates are extremely high among the Roma, starting from elementary and continuing into secondary education.

Map 5: Distribution of children (aged 10-13) not attending school in Acharnes and neighbouring Municipalities of Ano Liosia, Zefyri, Kamatero, Ilion, Aghioi Anargyroi, Nea Filadelfeia, Metamorfosi, Thrakomakedones, Kifissia, Nea Erythrea, Fyli, Aspropyrgos

Data source: Panorama of Greek Census Data 1991-2011 (https://panorama.statistics.gr/)

It is debatable whether middle class groups have a negative perception of disadvantaged residents. The responses of middle class parents about social mixing in schools were contradictory. Some middle class parents seemed to support social mixing in schools, on condition that this does not spoil the level of education services received by their offspring. Most middle class parents believe that children with different ethic-cultural backgrounds should have equal treatment in education, but their presence in the classroom becomes a threat and a risk for the educational progress of their own children. So, in order to avoid such potential disadvantage, they adopt strategies like sending their children to a different public school. However, school segregation does not lead to an increase of residential segregation since there has been no evidence of residential mobility related to the location of targeted schools.

Conclusions

According to our research findings there is no evidence of a general withdrawal of middle classes from public schools, apart from the minority of middle class parents opting for private schools. Instead, we observed a considerable withdrawal from the closest public school in the residential area and the transfer of pupils to other public schools in different neighbourhoods. Moreover, middle class parents adopt intervention strategies though schools’ associations in order to have more power and control over how pupils mix in classes, reinforcing segregation within schools. These middle class strategies are assisted by tactics adopted by school administrations supporting academic selectivity and isolation or expulsion of “undesirable” pupils. This distantiation tendency of the middle classes from the social tissue of neighbourhoods is also practically promoted by changing the limits of schools’ catchment areas, mainly near Roma settlements.

In spite of the broad range of middle class educational strategies, school segregation does not necessarily lead to residential segregation since it is not directly connected to residential mobility. However, school segregation intensifies social separation and educational inequalities.

Roma pupils are more segregated in schools than other social and ethnic groups. They are poorly integrated in schools and this is not connected to their particular cultural values, but mainly to failures of the public education system and the lack of a public education policy for Roma people. Similar issues are relevant for immigrant groups, although their integration to the local school system seems less problematic. It is necessary to redefine the shape of catchment areas, monitor the procedures of assignment of immigrants and Roma to special educational programs, and take appropriate measures in cases of early drop outs or other forms of exclusion. Schools cannot be separate from communities. Cooperation between schools and communities are necessary to implement positive social and economic changes for disadvantaged groups.

[1] UrAnU: Urban Analysis Units. They are a corrected form of Census Tracts (CT) used by ELSTAT in the sense that small CTs have been aggregated in order to avoid units with less than 900 inhabitants. This operation was performed to avoid confidentiality issues. Attiki is divided into 3.000 URANUs with an average population of 1.250 persons.

Entry citation

Vergou, P. (2017) Residential Segregation, Education and the City: Educational Strategies of Middle Class Groups in West Attica, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/segregation-education-and-the-city/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.74

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Βέργου Π (2016) Κοινωνικός Διαχωρισμός, Εκπαίδευση και Πόλη: Εκπαιδευτικές Στρατηγικές των μεσαίων στρωμάτων και Χωρική Ανισότητα στην Δ. Αττική. Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλίας.

- ΕΛΣΤΑΤ – ΕΚΚΕ (2015) Πανόραμα Απογραφικών Δεδομένων 1991-2011. Available from: https://panorama.statistics.gr/.

- Μαλούτας Θ (2016) Εκπαιδευτικές στρατηγικές των μεσαίων στρωμάτων και στεγαστικός διαχωρισμός στην Αθήνα. Επιθεώρηση Κοινωνικών Ερευνών 119(Α): 175–209.

- Andreotti A, Le Galès P and Fuentes FJM (2013) Controlling the Urban Fabric: The Complex Game of Distance and Proximity in E uropean Upper‐Middle‐Class Residential Strategies. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Wiley Online Library 37(2): 576–597.

- Atkinson R (2006) Padding the bunker: strategies of middle-class disaffiliation and colonisation in the city. Urban Studies, Sage Publications Sage UK: London, England 43(4): 819–832.

- Maloutas T (2007) Socio-Economic classification models and the contextual difference: The “European Socio-economic Classes” (ESeC) from a South European angle. South European Society and Politics 12(4): 443–460.

- Massey DS and Denton NA (1993) American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Van Zanten A (2001) L’école de la périphérie: scolarité et ségrégation en banlieue. Presses universitaires de France.