2017 | Apr

Cities of silence

Interwar Athens hides some surprises beyond and in addition to the violent population exchange between Greece and Turkey, beyond ‘savage urbanisation’ and especially refugee resettlement, which was then put to action – while today it is impossible to implement something similar for either refugees or native homeless populations and their ‘rescue’ from austerity [1]. The interwar period hides some surprises of a structural nature, touching the core of the developmental effort and the mobilisation of the population for its achievement, which should lead us to reflections about failures during the current crisis. In the refugee settlements, which were initially erected by international institutions and then developed spontaneously, hope flowered even where poverty was dwelling. It nested in shantytowns, in factories, in tavernas where rebetika songs were performed. The refugees were rebuilding their lives and innovated, renewing Greek culture, economy, society.

Athens urbanized rapidly since 1834, when it was declared the capital of a small country, Greece, which was surrounded by a changing international political and economic context. European neoclassicism emerged in the cityscape and in urban architecture, along with narratives about its Hellenic roots, which aimed at the reconciliation of Greek urban inhabitants with the imposed Bavarian administration and power (Bastea 2000). Colonial overtones in the Athens ‘hippodamean’ new urban plan also contributed in the subsumption of the new national identity to European modernism, in contrast with the ottoman past, which was inscribed in the labyrinthine neighbourhoods. Urban society was oscillating between locals and newcomers, comprador bourgeoisie and the diaspora, until the first factories emerged and the working class came to the foreground. Every historical transition reforged the cultural identity of citizens, with the consecutive transitions from comprador cultures in the 19th century to the conflictual working-class city in the early 20th century, and then the refugee inflow, which causes surprise with the emergent creative alternative cultures, on which we are focusing here.

Any urban researcher would be surprised by the sudden transition in 1922 from the ‘cities of silence’ – to borrow Antonio Gramsci’s (1971: 91) concept, who wrote about them during the interwar period from his prison – to the buzzing popular suburbanisation. Until the 1910s Athens and Piraeus had their landless proletariat, as well as what is today called the precariat, hidden in back alleys, excluded in miserable central slums hidden from the ‘sensitive eyes’ of the bourgeoisie, just as Engels (1969) described for the working-class neighbourhoods of Manchester (Pooley 1992). Tenants without infrastructure, but also without any prospects for improvement of their housing space, were overcrowded in these slums of despair, in shacks and rented rooms, which created a sort of dotted social segregation in space, with miserable enclaves in the centre of the city (Λεοντίδου 1989/2013: 137-45, Leontidou 1990/2006: 67-70).

However, since 1922 the slums of despair give way to extensive slums of hope (Stokes 1962, Turner 1968, Λεοντίδου 1989/2013, Leontidou 1990/2006: 84-8). This is a paradox, since the violent relocation of refugees, instead of misery, inaugurated a period of creativity and substituted the ‘cities of silence’ with vivacious popular suburbs. The refugee inflow rendered the poverty pockets of the landless proletariat a minority in a city, which started expanding with popular self-built settlements and owner-occupation – even if in shacks and shanties (Λεοντίδου 1989/2013: 216-8).

The retrospective surprise of the substitution of despair for hope in the popular settlements after 1922, is conducive to a reflexion on the ‘cities of silence’ and spontaneous urbanization. It is wrong to believe, as usual, that popular self-built settlements and the informal economy constituted a traditional activity and were a relic of the precapitalist past. In Greece, they emerged with the onset of peripheral capitalism (Leontidou 1990/2006, 1993a), and after those miserable slums of North European capitalism had appeared in the city (Pooley 1992).

Refugee restitution and self-built settlements

The violent expulsion of the Greeks from the Asia Minor coasts started in 1922, before the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), which institutionalized the population exchange after the Asia Minor disaster. Those years, 1.200.000 refugees arrived in Greece (of 5 million inhabitants) and 500.000 Turks left. The refugees constituted a heavy presence in comparison with the 60.000 people stranded today in Greece (of 11 million inhabitants). In 1920-28 the population of the Athens basin suddenly doubled from 453.042 to 802.000, and then kept increasing with the rapid internal migration, to reach 1.124.109 in 1940 (Λεοντίδου 1989/2013: 158).

The first months after their arrival, the refugees settled wherever they could find a place, occupying not only land, but also train wagons, archaeological spaces, churches, and even the stalls of the Municipal theatre of Athens (Ziller’s architectural work, unfortunately torn down by Kotzias – see photo 1). The Greek government and the international organizations acted instantly, with a determination which is unthinkable today. In haste, the Fund for Refugee Assistance (henceforth FRA) was established in November 1922 for temporary relief. The settlements built by the FRA were immediately surrounded by shacks and shanty towns. Cities were flooded by shacks everywhere, even within the ancient agora and within river beds, with the emblematic Ilissos settlement (Λεοντίδου 1989/2013: 154). These settlements were by no means comparable with today’s migrant and refugee camps in Greece and the feeling of confinement which they bring about.

Photo 1: Temporary settlement of the 1922 refugees, each family is housed in a box of the Municipal Theater of Athens

Source: Hellenic Literary and Historical Archive, published online and as cover of LiFO, n. 498, 1.12.2016

A year later, in November 1923, the Refugee Settlement Commission (henceforth RSC) assembled for the first time in Thessaloniki, under the auspices of the League of Nations in agreement with the Greek government, and the FRA was dissolved in 1925. The RSC did not deal with temporary relief, but with the restitution of the refugees in residence and productive activity in multiple ways, from rural reform and loans to small businesses, to the building of housing estates at a large scale and the development of site and services (Turner 1968, Λεοντίδου 1989/2013: 214-5) for more affluent refugees. Other institutions operated in parallel, such as the National Bank of Greece and the Ministry of Social Welfare, which undertook refugee resettlement after 1930, when the RSC was dissolved (Γκιζελή 1984).

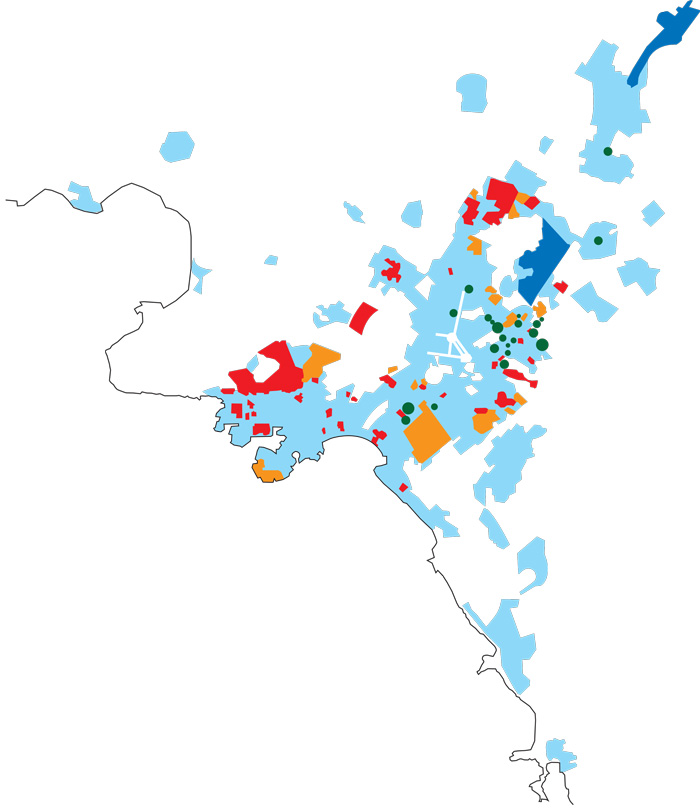

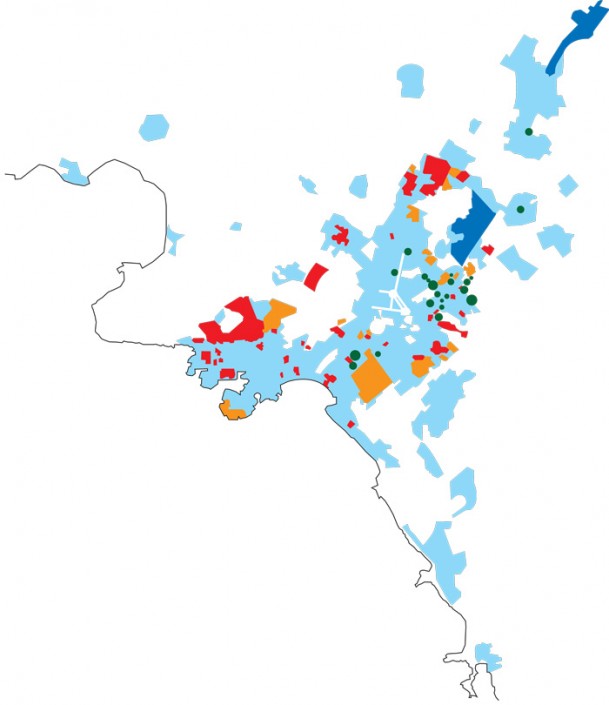

The urban policy of the RSC in the capital of Greece started with the selection of four neighbourhoods, where those emblematic refugee communities were established, which played a pivotal role during the years of occupation, resistance and the civil war in the 1940s. In Nea Ionia, Kaisariani and Byron, at a distance of 4 km from the Athens centre, 3864, 1998 and 1764 houses were built, respectively, and 5584 houses were added in Nea Kokkinia (Nikaia) near Piraeus, where a refugee settlement pre-existed (Λεοντίδου 2002). Permanent refugee homes were also built in Pagrati and Kallithea. In other neighbourhoods different arrangements were offered, especially where housing cooperatives were active, such as sites and services in Nea Smyrni, for example (see map 1).

Map 1: Refugee settlements, housing cooperatives and garden-cities.

| Refugee settlements built by the RSC and the state are represented with the red colour. Those built in land plots granted by the state with the orange colour. The bourgeois “garden-cities” (Psychico, Filothei, Ekali) with the blue colour.

The housing cooperatives 1923-1925, by land area expropriated (from 2000 to 174.000 sq.m), are represented by proportional circles, in dark green colour The 1940’s city plan is represented with light blue color The map derives from the book by Lila Leontidou (Λεοντίδου 1989/2013) p.208. , based on the data mapping from different sources and archives. First published in the Papyrοs-Larousse-Britannica Encyclopaedia first edition under the entry “Athens” by L.Leontidou (Λεοντίδου 1982), vol.3, p.400 |

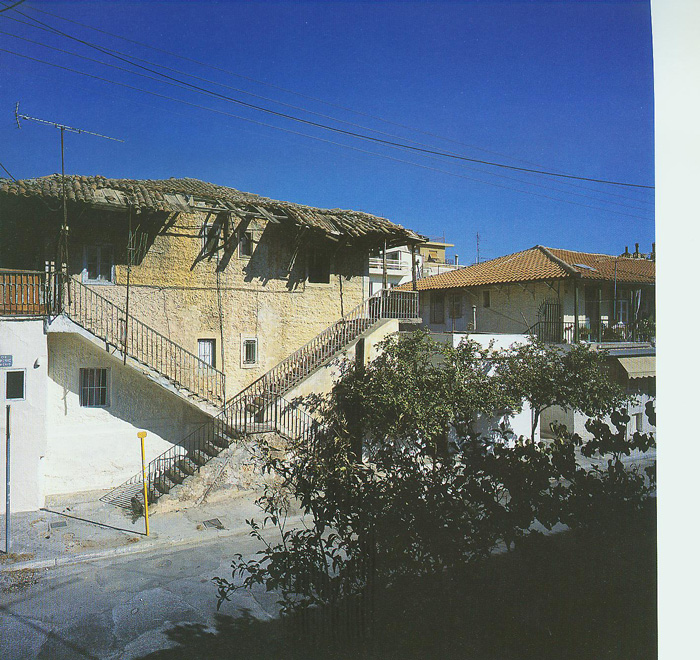

The beautiful minimalist architecture of these first RSC communities and later those of the Ministry of Social Welfare still adorns the urban landscape, although the communities gradually submit to the monotonous modernity of the multi-storey apartment building. Besides the rows of houses, which were interrupted by settlers’ initiatives, there were original elements inexistent elsewhere in the city, such as the criss-cross stairways in the oblong two-storey houses of Nikaia around the patios with the wells and the gardens, the “doll’s houses” of Kaisariani with the flower pots and the embroidered curtains, and further the later stone houses there and in Petralona. The simple forms were differentiated by the personal labour by refugees, who varied the homogeneous houses, creating polymorphic neighbourhoods. The rooms were multi-functional, due to the narrowness of space. But even this confined internal space was no problem, because everyday life was extended to patios and yards, which also served as laundries and workshops, to doorsteps and pavements for informal socializing, to empty plots which became playgrounds for the children, and to piazzas, which converted public space into common space, presaging today’s ‘commons’ of the period of the crisis (Leontidou 2015a,b, Gritzas & Kavoulakos 2015).

Photo 2: Refugee residence in Nikaia (criss-cross stairways)

Source: Photo by Spyros Delivorias, from the book by the Nikaia Municipality (Δήμος Νίκαιας 2002)

The care for the common spaces was mainly a female concern and demanded cooperation and solidarity for the collective solution of everyday difficulties. The coffee bars, kafeneia, were the privileged space of men, and the exclusion of women was absolute and unnegotiable. Women were burdened with a heavy volume of housework. This included practical matters arising by the lack of infrastructure, such as the need to carry water, fire wood, to arrange for heating and garbage collection. In essence, this constituted collective provision of social welfare, medical care, education, care for the children, but also aesthetic upgrading of the housing space. In 2002 a grandmother in Nikaia proudly referred to the vivacious colours of ochre and blue on the walls of her house: “This is my mountain, this is my sea” (Λεοντίδου 2002: 19). Foreign researchers in Nikaia’s Germanika settlement in the 1970s were searching for the shared kitchens customary in Northern working-class housing estates and wondered why the Greek women insisted in having their own family kitchens, no matter how small, which they would not share, not even with relatives (Hirschon 1989). But, the women, however confined, developed mutual aid, collective behaviour and solidarity, which was rare in Greece at the time. This carried them beyond the confinement of housework and also artisan activity. Many women also became industrial workers.

Every family took care of ‘its own’ shack, gradually upgrading it as savings permitted. First, it would transform it to a ‘doll’s house’, then it expanded its space by adding rooms horizontally or vertically (‘panosikomata’) for the next generations. Many families also maintained workshops and cottage industries with the house as a basis, creating a buzzing informal economy (Leontidou 1993, Λεοντίδου 1997). These options, offered by rudimentary owner-occupation, sustained hope in the poor neighbourhoods at the urban periphery – initially refugee communities, soon afterwards areas where cityward migrants from rural areas settled. These were the slums of hope.

Socio-geographical exclusion and spontaneous urban expansion

Descriptions of the beautiful indigenous architecture of the ‘spotless slums’ (Hirschon 1989: 1-4, Sandis 1973) all include some measure of romantic overstatement, if we take into account poverty and chaotic inequalities. Not only did social exclusion in space persist, but it was planned, with the division between natives and refugees at its epicentre. The whole Greek area, moreover, saw the division between towns of natives and refugee towns, but also racist attacks and arson of refugee communities in Northern Greece (Λεοντίδου 1989/2013: 161-4).

In Greater Athens the RSC became in effect the ‘urban planner’ of urban expansion, actually practicing segregation: the 12 main and 34 smaller refugee settlements which it created were at a distance of 1-4 km from the boundaries of the built-up area of 1920 (Λεοντίδου 1989/2013: 209), so as “not to disturb the ‘normal’ life of the existing city”, as it was bluntly declared (Παπαϊωάννου 1975: 14). A little later, institutions built in more central areas, such as Alexandras Avenue and Petralona. However, the insistence on the periphery can be substantiated by quantitative data, especially with population stability in central Athens, which in 1920-28 increased only by 91.896 inhabitants (from 292.835 to 384.731, a difference just over the natural increase of the population), in contrast with the suburbs, which saw a spectacular increase three times higher, by 257.062 inhabitants (from 160.207 to 417.269 – calculated from tables in Λεοντίδου 1989/2013: 330-1).

Except the planned socio-geographical exclusion, achieved through the location of refugee settlements on the urban periphery, there were also other intentions in the policy implemented by the RSC. First of all, in owner occupation: the creation of a large population of petty home owners, rather than a landless proletariat, was considered as an aversion of the communist danger! This has been stated for the refugees in Macedonia and Thrace in 1929 (Mavrogordatos 1983: 146, 215), but there were also frequent references to cities, such as the one by Pentzopoulos (1962: 195), that “the better housed refugees of the suburbs of Nea Smyrni and Kallithea proved to be more law-abiding citizens than certain natives, who espoused communism”.

For the same reasons, self-government in refugee towns was discouraged, in contrast with rural areas. Peasants were encouraged to form legally constituted associations, and the government representatives allocated the land to councils elected by the heads of families. In the cities, by contrast, the refugees were settled on the basis of waiting lists, except the more affluent ones, who formed building cooperatives (Λεοντίδου 1989/2013: 235-6). There is no reference to any self-government in the large communities of Athens and Piraeus. The RSC kept their administration until 1930, when it was substituted by local authorities.

However, these policies either failed or were undermined on all levels. Initially the small proprietors organized themselves in ‘embellishing associations’, but later acted subversively: they created the ‘red enclaves’ on the periphery of Athens and Piraeus, initially Venizelist, and later communist ones. As to self-building and owner-occupation, these triggered an unprecedented urban sprawl already in 1925. In effect, the Greek government and the RSC had decided only the direction towards which the capital would expand; but the volume and the degree of expansion and population increase of the new settlements had escaped their control almost immediately (Λεοντίδου 1989/2013: 209-11). In this sense, the RSC and the government failed as urban planners. The process of popular building and illegal settlement had begun.

They also failed as regional planners, who would turn the massive refugee inflow towards the rural areas: migration was sliding towards the cities. During the population census of 1928, while refugees were equally represented in towns and rural areas, they constituted 27,68% of the urban population (of 2 million), and only 12,47% of semi-urban and rural population (of 4 million): in other words, they had over-double weight in cities, with an average annual rate of increase of 6,29% in 1920-28, in comparison with one-third of that in the countryside and an average of only 2.69% in Greece as a whole (Λεοντίδου 1989/2013: 162-3). This was the beginning of fast urbanization and uncontrolled urban expansion, which since then came to characterize the Greek social formation.

It is not quite clear, whether this constituted a failure, or regional policy choices of the institutions were purposeful. In any case, it has been claimed that initially the concentration of refugees in the capital was linked with electoral interests of the Liberal Party, who put to action a peculiar type of gerrymandering, i.e. an electoral strategy which manipulated population densities rather than boundaries of electoral districts (Pentzopoulos 1962: 182). By 1934 the populists under Tsaldaris created “their own masterpiece” of electoral strategy, the traditional type of gerrymandering (Mavrogordatos 1983: 314-16), i.e. the purposeful delimitation of electoral districts, so as to increase their possibilities of winning in critical regions.

The bourgeoisie also developed strategies of geographical relocation and exclusion, which continued the spatial and social polarization of previous periods. The gap widened, between the emergent working class in refugee settlements on the one hand, and the bourgeoisie in the ‘garden cities’ of Psychiko, Filothei, Ekali on the other. The ‘other’ suburbs were not born out of wealth alone, but also out of power and the influence exercised by the bourgeoisie on planning legislation and the direction of urban infrastructure. The building code of Psychiko – especially the planning by-laws, the ‘minimum’ (large) plot and housing sizes allowed, the (low) heights of buildings and the forbidden land uses – constituted a mechanism of social segregation and exclusion of less affluent social groups. In fact, the bourgeoisie created something like ‘gated communities’, and in any case exclusive areas, in the context of interwar refugee inflow (Λεοντίδου 1989/2013: 222-3). During the same period, the middle-class apartment building appeared, as a sort of in-between space in social and urban structure.

In any case, in the urban suburbs the popular strata have been acting independently. Disobedience to planning (and other) rules, as well as spontaneity evidenced by the refugees have since marked urban development decisively (Leontidou 1990/2006, 2014); and they have brought about a mounting urban expansion, which has altered the urban structure of the capital of Greece, surrounding the city with irregular layouts and illegal settlements. In the peri-urban area where a mere 6% of the urban population used to live in 1920, 44% were living in 1940 (Λεοντίδου 1989/2013: 207-8). The city climbed on the slopes of Hymettus and Aegaleo mountains and reached until the Penteli monastery. The approved master plan (without counting the illegally settled area), after successive ‘legalizations’ of already settled areas, in the context of populism in different periods, quadrupled in 1920-1940, from 3264 to 11600 hectares (Λεοντίδου 1989/2013: 211).

Spontaneous urbanization was due initially to the refugees, but soon internal migrants joined in, initially those moving out of Northern refugee towns – but that is another story (Λεοντίδου 1989/2013: 164). The refugees showed the way to the future, since illegal building was generalized and a multitude of migrants surrounded the cities with extensive popular suburbs. The population now claimed more rights in the direction inaugurated by the State and international institutions. They claimed settlement and labour rights, the ‘right to the city’ (Leontidou 2010, 2012, 2014). Housing held a crucial role in this, as a means of production, since it constituted a basis for informal work and cottage industry (Leontidou 1993b).

Spontaneous urban development and the slums of hope came to be the rule for popular housing. For at least five decades, a traditional right of the bourgeoisie – the opening of new land to urbanization – was extended to the poor, the refugees, the proletariat. By 1940 the popular strata, who constituted almost three-fourths of the urban population, controlled one-third of the urban settled area. Although quantification is difficult, we have estimated that in 1940-70 about 450.000-500.000 people were housed illegally on the outskirts of the Athens (Leontidou 1990/2006: 150).

Reflection on today’s city of the crisis

Reminiscing the interwar period, we realize that the essence of developmental efforts has been now forgotten in the European Union of neoliberalism and the crisis. Then, like now, Greece was under international economic control. But what a difference from today’s impasse of austerity… Today, despite Greece’s incorporation in the EU as a full member state, instead of supporting development, quality of life, sustainability and innovation, instead of taking advantage of the people’s dynamism with the empowerment of popular action and spontaneity (Leontidou 2015a), rulers opt for imposed austerity, which, moreover, goes in parallel with full control of everyday life. The frontal attack for the destruction of the informal economy and petty-building in Greece today (Leontidou 2014, 2015a), renders the early period of owner-building rather original and subversive. Popular spontaneous and illegal settlements were ‘clamped down’ during the period of dictatorship (1967-74) with ‘legalizations’ and demolitions, and the last straw was given after EU accession (Leontidou 1990, 2014, 2015b). After this, the crisis created homeless populations who once used to live in shacks or in the context of the extended family in small owner-occupied homes and were sustained by income sharing.

Moreover, today housing is burdened by a strategy of taxation, which takes advantage to the highest degree of the particularity of the generalization of petty owner-occupation in Greece since the years of its support by the RSC: every small property will pay the sizeable property tax, ENFIA, corresponding to an overestimation of its ‘objective value’. With this, and with the indebtedness haunting the population, always according to the ‘troika’ (IMF- ECB- European Commission) and the governments, the city streets are full of homeless people, even before the start of the process of confiscations.

So what do memories of the 1920s tell us about today’s European civilization, or rather barbarism? If policies like those of today were implemented during the interwar period, we would have completely missed resettlement, improvement of the quality of life of popular strata, and the rise of the middle class. What is worst in today’s Athens of the crisis, what has been blown and it is doubtful whether it will come to life again, is what the refugees carried with them, what they offered to the native populations, which carried them along to struggles for the improvement of their quality of life, at the same time turning the belts of development and progress in the interwar period: what has been blown is hope.

[1] Revised version, with additional references, of the first three sections of the publication by Λεοντίδου 2016 in LiFO, issue 498, 1.12.2016, pp. 50-59 (in Greek, cf. http://www.lifo.gr/articles/archaeology_articles/123864).

Entry citation

Leontidou, L. (2017) Slums of Hope, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/slums-of-hope/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.70

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Γκιζελή Β (1984) Κοινωνικοί μετασχηματισμοί και προέλευση της κοινωνικής κατοικίας στην Ελλάδα 1920-1930. Αθήνα: Επικαιρότητα.

- Δήμος Νίκαιας (2002) Τα προσφυγικά σπίτια της Νίκαιας. Προύσαλη Ε (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Εκδόσεις Λιβάνη.

- Εταιρεία Σπουδών Νεοελληνικού Πολιτισμού και Γενικής Παιδείας (1997) Ο ξεριζωμός και η άλλη πατρίδα: Οι προσφυγουπόλεις στην Ελλάδα. Στο: Επιστημονικό συμπόσιο, 11 και 12 Απριλίου 1997, Αθήνα: Σχολή Μωραΐτη, σ 372.

- Λεοντίδου Λ (1982) Αθήνα 1834-1981: Οικονομική, κοινωνική και οικιστική δομή του σύγχρονου πολεοδομικού συγκροτήματος. Πάπυρος- Larousse- Britannica 3: 388–414.

- Λεοντίδου Λ (1989/2013) Πόλεις της Σιωπής. Εργατικός εποικισμός της Αθήνας και του Πειραιά, 1909-1940. 3η έκδ. Αθήνα: ΠΙΟΠ.

- Λεοντίδου Λ (1997) Η άτυπη οικονομία ως απόρροια της προσφυγικής αποκατάστασης. Στο: Εταιρεία Σπουδών Νεοελληνικού Πολιτισμού και Γενικής Παιδείας (επιμ.), Ο ξεριζωμός και η άλλη πατρίδα: Οι προσφυγουπόλεις στην Ελλάδα, Αθήνα: Σχολή Μωραΐτη, σσ 341–368.

- Λεοντίδου Λ (2002) Ένας χώρος ελπίδας κι αρχιτεκτονικής πρωτοβουλίας: Άτυπη εργασία και κατοικία στις προσφυγικές γειτονιές της Νίκαιας. Στο: Προύσαλη Ε (επιμ.), Τα προσφυγικά σπίτια της Νίκαιας, Αθήνα: Εκδόσεις Λιβάνη, σσ 17–23, 46–47.

- Λεοντίδου Λ (2016) Φτωχογειτονιές της ελπίδας. LiFO 498: 50–59.

- Παπαϊωάννου Ι (1975) Μέρος I: 1920-1960. Στο: H κατοικία στην Ελλάδα: Κρατική δραστηριότης, Αθήνα: Τεχνικό Επιμελητήριο Ελλάδας, σσ 5–40.

- Τεχνικό Επιμελητήριο Ελλάδος (1975) H κατοικία στην Ελλάδα: Κρατική δραστηριότης. Αθήνα: Τεχνικό Επιμελητήριο Ελλάδας.

- Bastea Ε (2000) Τhe Creation of Modern Athens: Planning the Myth. Cambridge U.P., New York

- Clarke J, Huliaras A and Sotiropoulos D (2015) Austerity and the Third Sector in Greece: Civil Society at the European Frontline. Clarke J, Huliaras A, and Sotiropoulos D (eds), London: Ashgate.

- Engels F (1969) The condition of the working class in England. London: Panther

- Gramsci A (1971) Selections from the prison notebooks. New York: International Publishers.

- Gritzas G and Kavoulakos KI (2015) Diverse economies and alternative spaces: An overview of approaches and practices. European Urban and Regional Studies, SAGE Publications 23(4): 917–934.

- Hirschon R (1989) Heirs of the Greek catastrophe: The social life of Asia Minor Refugees in Piraeus. New York: Berghahn

- Leontidou L (1990/2006) The Mediterranean city in transition: Social change and urban development. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leontidou L (1993a) Postmodernism and the city: Mediterranean versions. Urban Studies, Sage Publications 30(6): 949–965.

- Leontidou L (1993b) Informal strategies of unemployment relief in Greek cities: the relevance of family, locality and housing. European Planning Studies, Taylor & Francis 1(1): 43–68.

- Leontidou L (2010) Urban social movements in ‘weak’civil societies: The right to the city and cosmopolitan activism in Southern Europe. Urban Studies 47(6): 1179–1203.

- Leontidou L (2012) Athens in the Mediterranean ‘movement of the piazzas’ Spontaneity in material and virtual public spaces. City, Taylor & Francis 16(3): 299–312.

- Leontidou L (2014) The crisis and its discourses: Quasi-Orientalist attacks on Mediterranean urban spontaneity, informality and joie de vivre. City, Taylor & Francis 18(4–5): 546–557.

- Leontidou L (2015a) ‘Smart cities’ of the debt crisis: Grassroots creativity in Mediterranean Europe. The Greek Review of Social Research 144(Α): 69–101.

- Leontidou L (2015b) Urban social movements in Greece: Dominant discourses and the reproduction of ‘weak’ civil societies. In: Clarke J, Huliaras A, and Sotiropoulos D (eds), Austerity and the Third Sector in Greece: Civil Society at the European Frontline, London: Ashgate, pp. 86–106.

- Mavrogordatos GT (1983) Stillborn Republic: Social Coalitions and Party Strategies in Greece, 1922-1936. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Pentzopoulos D (1962) The Balkan exchange of minorities and its impact upon Greece. Athens and Paris: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers.

- Pooley CG (1992) Housing strategies in Europe, 1880-1930. London: European Science Foundation & Pinter Publishers.

- Sandis E (1973) Refugees and economic migrants in Greater Athens. Athens: NCSR

- Stokes CJ (1962) A theory of slums. Land economics, JSTOR 38(3): 187–197.

- Turner JC (1968) Housing priorities, settlement patterns, and urban development in modernizing countries. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, Taylor & Francis 34(6): 354–363.