2020 | Apr

The study area in Tavros is one of the settlements created to accommodate Asia Minor refugees of the 1920s in Athens (such as Dourgouti, Asyrmatos or Ampelokipoi). The refugees in Tavros were housed either in self-made shacks or in apartment blocks built by the state. After the 1920s, the neighbourhood received a large number of internal migrants. The gradual process of public housing production to replace the shacks, where refugees and internal migrants had previously lived, began in 1950. Unlike other refugee settlements (such as Ilissos, Polygono or Kountouriotika) where the traces of these settlements completely disappeared as they were progressively fully absorbed by their surrounding areas, Tavros eventually preserved its particular characteristics with the construction of the social housing estates.

The neighbourhood’s location

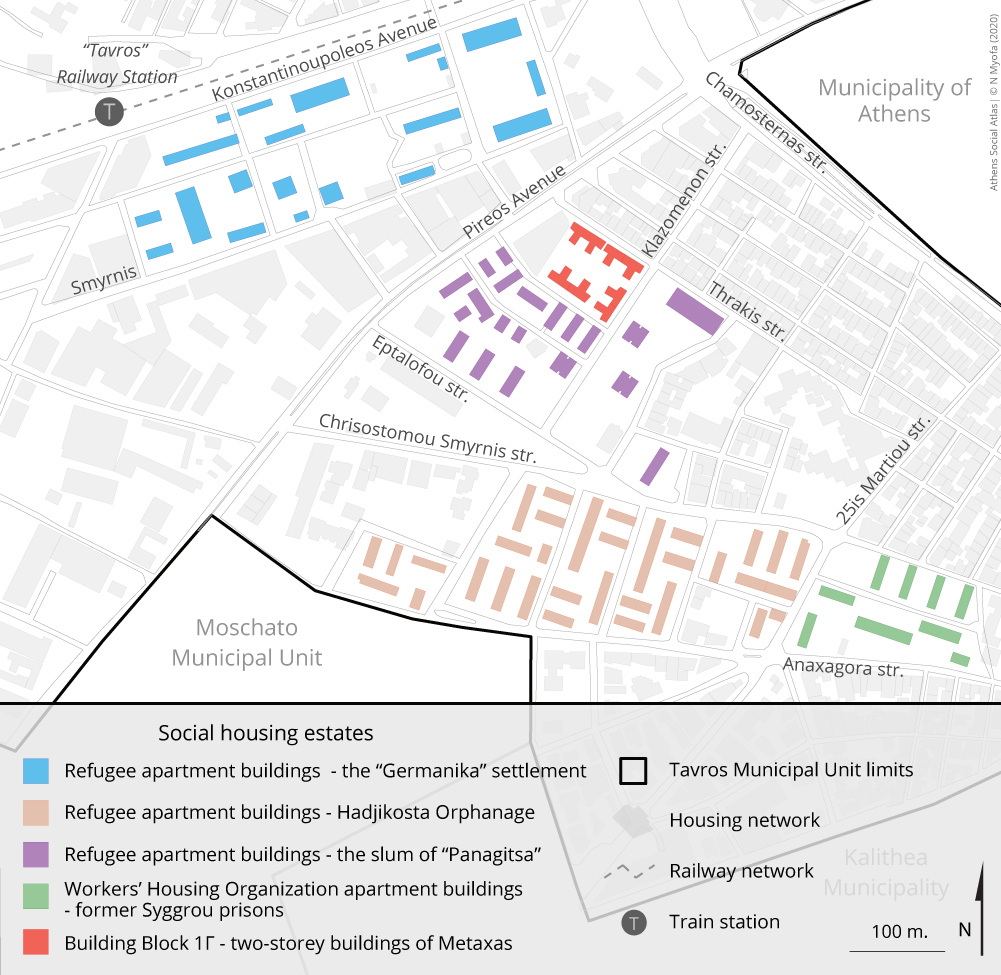

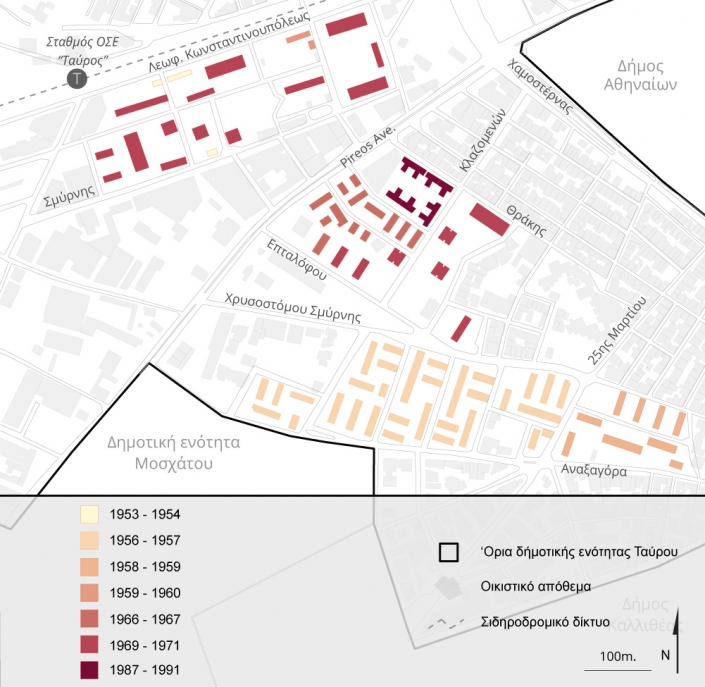

The social housing estates neighbourhood of Tavros is located in the southern part of the community’s municipal unit [1] (Map 1). Tavros is located near the centre of Athens and Piraeus (3.5 km and 5 km, respectively). It is easily accessible using Peiraios Avenue which is well serviced by public transport.

Map 1: The neighbourhood

There are 89 apartment blocks in the housing estate which were built from the mid-1950s to the late 1980s to accommodate refugees and internal migrants who had previously lived in inadequate housing conditions (Map 2).

Map 2: Tavros’ refugee settlements

The story of the neighbourhood: the settlement of refugees in the 1920s

Tavros’s refugee settlement was created outside the city plan of Athens by refugees from Smyrna, Antalya, Ikonio and other coastal areas in Asia Minor following the Greek national ‘disaster’ after its defeat by Turkey in the Asia Minor Campaign and the subsequent signing of the Lausanne Treaty in 1923. The name of the neighbourhood originates from the Tavros Mountains which are in the ‘lost homeland’ of Asia Minor. However, the first name of this refugee settlement was Nea Sfageia [2] until 1934 when the area became an autonomous community, and the community council changed the name of the area to Tavros.

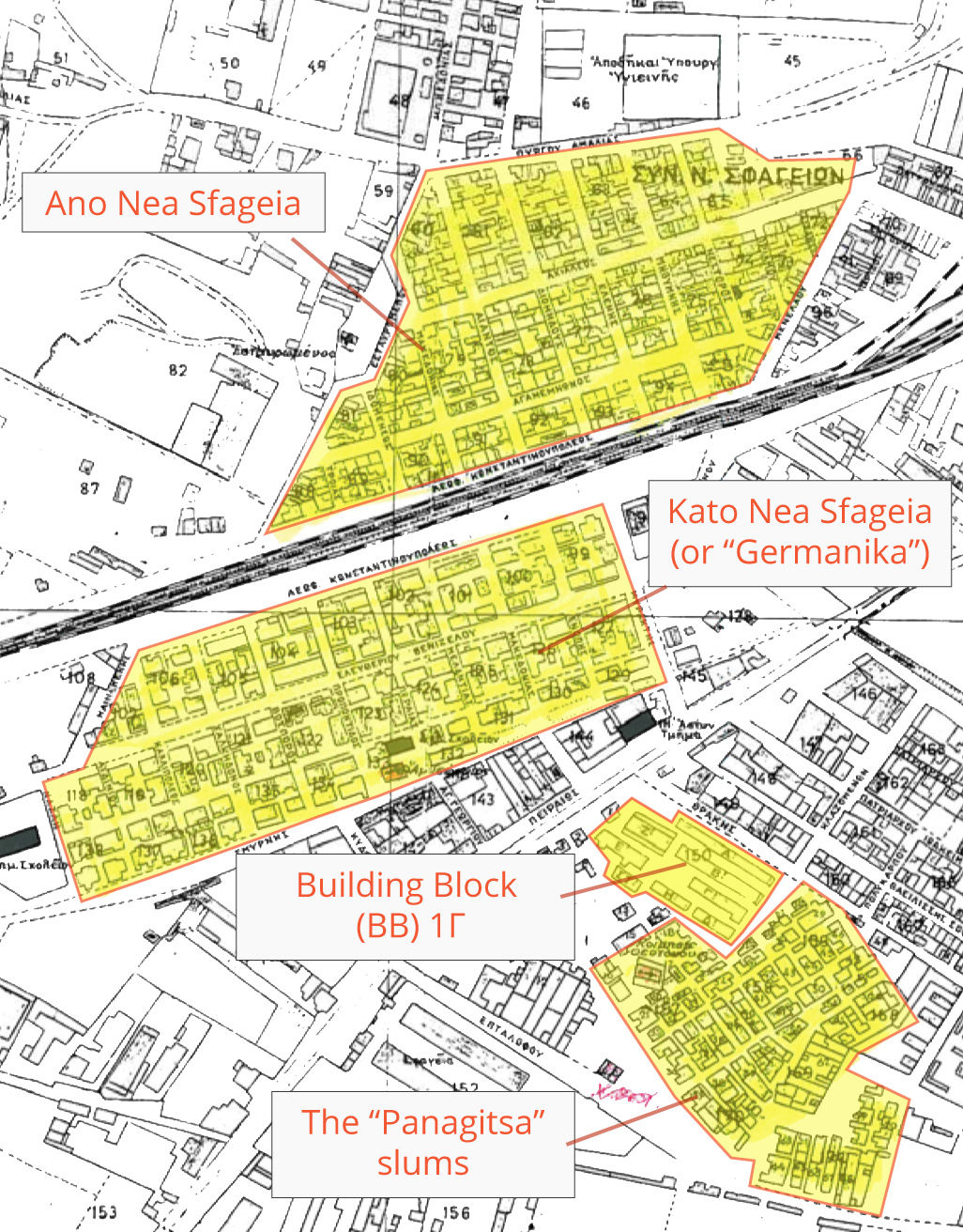

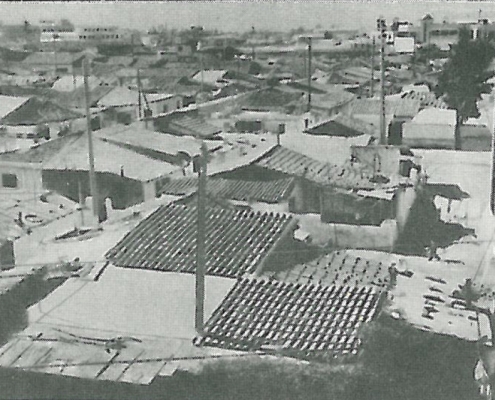

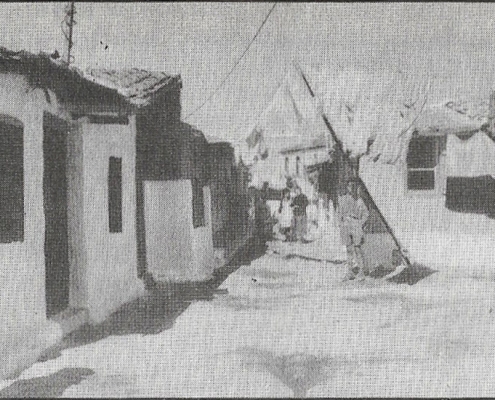

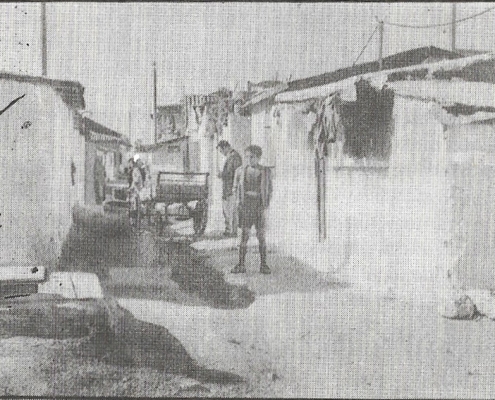

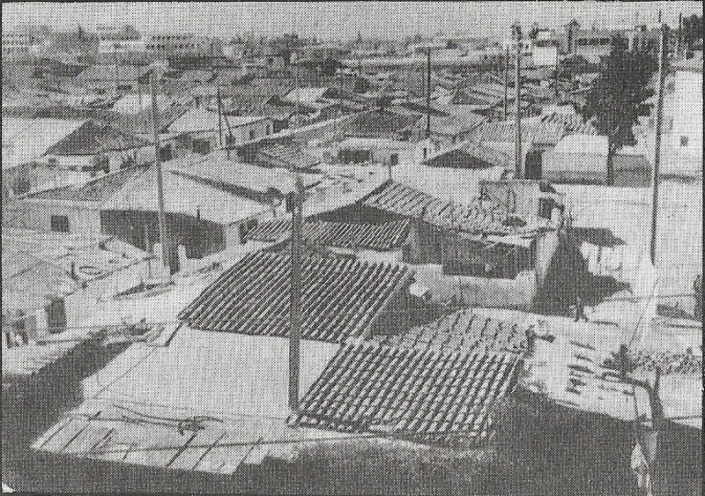

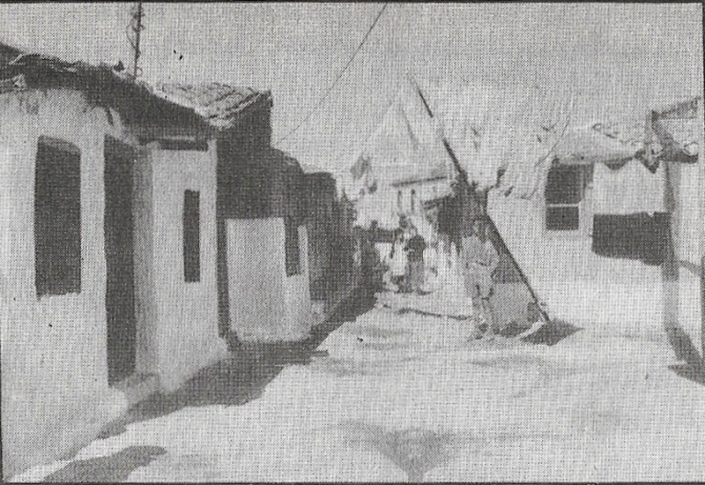

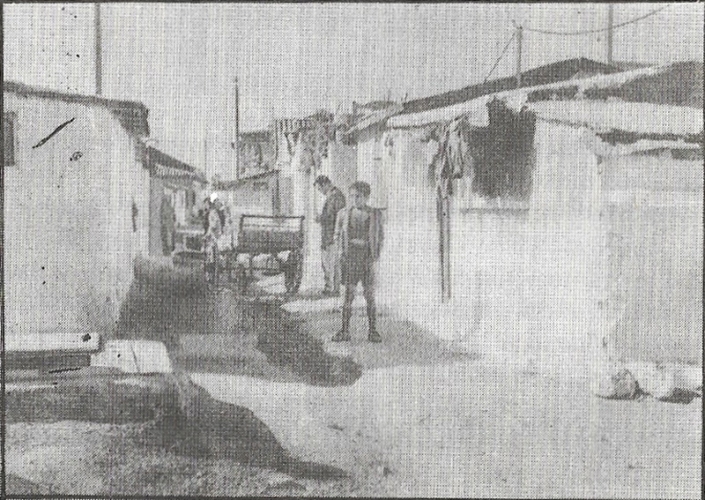

Before the settlement of the refugees, the area was almost uninhabited. There were only farms. The settlement of refugees in Tavros took place from 1922 to 1927. They settled mostly in shacks that were constructed either by the state or by the refugees themselves. The Tavros refugee settlement was subdivided into districts according to the churches that existed there. Thus, the names of the districts were the slum of ‘Panagitsa’, the ‘Agios Georgios’ (‘Germanika’ shacks) and the ‘Estavromenos’ [3] (Figure 1) (Papadopoulou and Sarigiannis, 2006: 183).

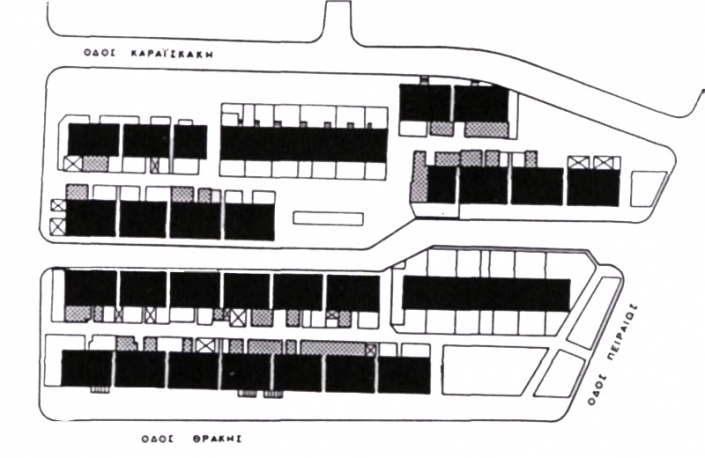

The first group of shacks, the slum of Panagitsa, was located southeast of Piraeus Street, and the second group, Germanika, was located northwest of Piraeus Street (Figure 1). These two areas constituted ‘national lands’ which, at the establishment of the modern Greek state in 1827, came under its jurisdiction. Later, the state gave the national lands to Asia Minor refugees for their housing. The first refugee settlement was in Panagitsa in shacks made by the refugees themselves (Figures 2, 3 & 4) Later, during the period 1925–1927, this was followed by the second refugee settlement at Germanika; this site was more organized. Germanika was made up of prefabricated wooden shacks and built with money that Germany had paid to Greece as reparation claims after WWI (Σούτος, 1983: 93, 105-109).

Figure 1: The four areas of refugee settlement in Tavros

Source: Παπαδοπούλου, Σαρηγιάννης, 2006: 183 και ιδία επεξεργασία

Figure 2-4: The slum of “Panagitsa”

Due to the housing rehabilitation of refugees in Tavros, the need for their vocational rehabilitation became a concern. The area was soon transformed into an industrial zone where refugees, a low-cost labour force, could work. In addition, due to the existence of slaughterhouses, there were many leather processing factories.

Internal migrants’ settlement during the post-war period

Internal migrants from various parts of Greece settled in Tavros because of the Civil War (1946-1949) and their need for jobs. In the area, there were municipal slaughterhouses, as well as several craft businesses where the newly arrived people could be employed. Internal migrants who could not afford to buy a regular dwelling, since 1945, settled into the area of the abandoned former Syggrou prisons [4]. More specifically, they occupied the abandoned buildings (cells) or constructed temporary dwellings themselves. Within a short period of time, more than 200 families were settled here (Σούτος, 1983: 211).

Beginning in 1950, the state made great efforts to move the settlers from this area. However, the residents founded the Settlers’ Association. The main aim of the association was to advocate that the settlers’ housing rehabilitation should take place in the area of their temporary housing (Σούτος, 1983: 212).

Eventually, the temporary dwellings were demolished, and nine apartment buildings were constructed to house the internal migrants. The construction was completed in 1959, and the apartments were given to the beneficiaries during the period from 1960–1961 through a lottery selection process (Figure 5) (Σούτος, 1983: 213-214).

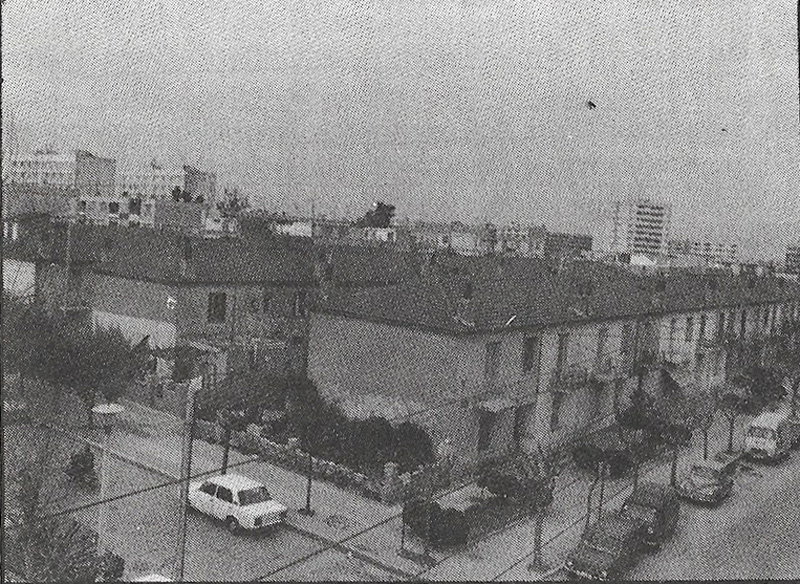

Figure 5: One of the apartment buildings that was constructed at the site of the former Syggrou prisons to house the internal migrants

The construction of social housing estates

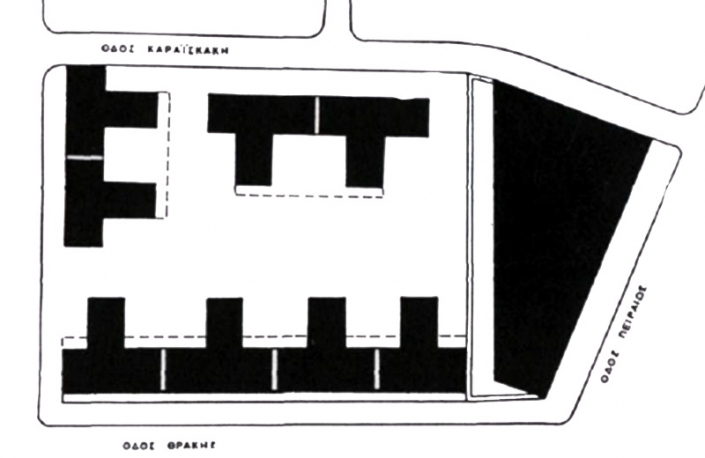

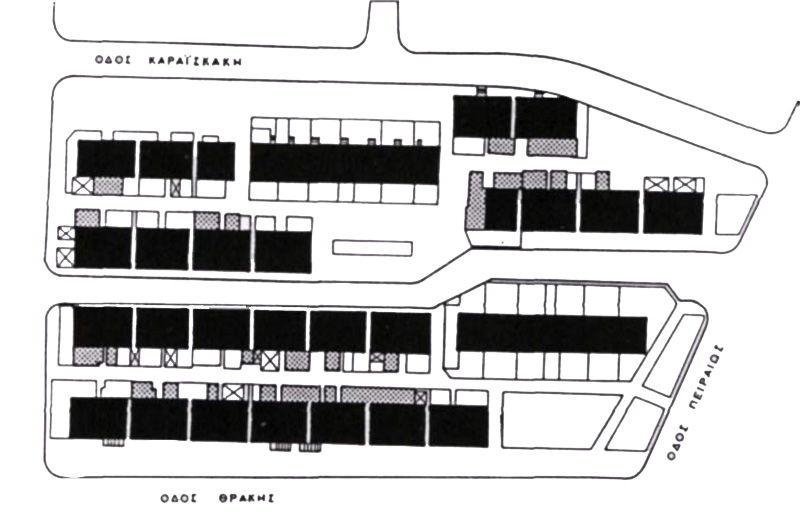

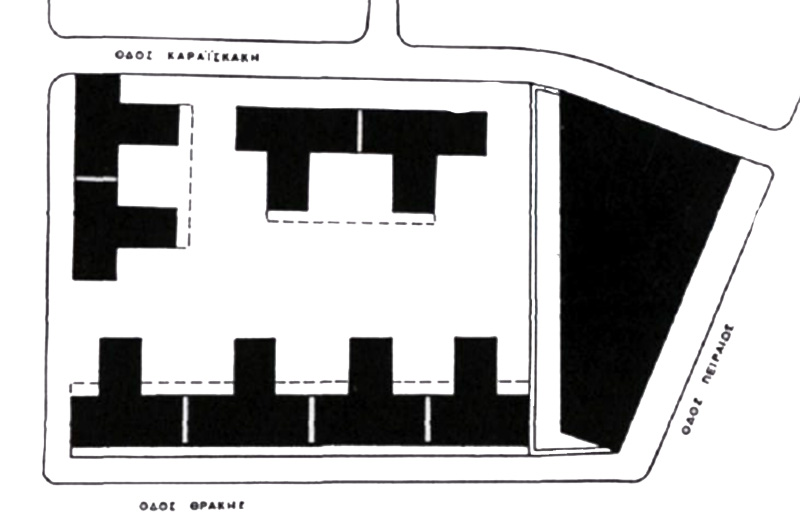

The first apartment blocks of Tavros for the settlement of refugees were built in 1936 and 1950 after the demolition of part of Panagitsa’s slum. In these eight apartment blocks (Figure 6a and 6b), refugees who had mainly dwelled in the shacks of this slum area were housed (Σούτος, 1983: 105). According to the interviewees, residents of the neighbourhood, this social housing estate was known as the ‘two-storey buildings of Metaxas’, because they were built during the Metaxas dictatorship, 1936-1941 (Μυωφά, 2019) (Figure 7).

Figure 6a: Plan of the building block (BB 1Γ) in Tavros before the regeneration

Figure 6b: Plan of the building block (ΒΒ 1Γ) in Tavros after the regeneration Figure 7: The first apartment block for refugees in Tavros

Figure 7: The first apartment block for refugees in Tavros

Six of these apartment blocks consisted of two-storey buildings and were constructed in 1936 by the Ministry of Welfare; the other two consisted of three-storey buildings constructed in 1950 by the Ministry of Reconstruction. They were 136 very small apartments of 39–45 m2 in the two-storey buildings and 35–56 m2 in the three-storey buildings (Λουκόπουλος κ.ά., 1990: 33).

Map 3: Number of storeys per apartment building in the Tavros social housing estates

The construction of the refugee apartment blocks began gradually in the 1950s, and they were constructed either in slum areas after the demolition of the shacks or in other areas purchased by the state after expropriation. Firstly, in the period from 1953–1954, six apartment buildings (three and four storeys) were built after the demolition of some shacks in Germanika. Afterwards, in the period from 1956–1957, 32 four-storey apartment buildings were constructed in the area of the Hadjikosta Orphanage which was purchased by the Ministry of Welfare after expropriation (Σούτος, 1983: 105, 192). Next, a broader programme of shack demolition took place in Panagitsa’s slum. More specifically, in place of the shacks, 12 four-storey apartment blocks were constructed during the period from 1966–1967. In the period from 1969–1971, another eight apartment blocks, mainly high-rise buildings, were built (two of six-storey, three of seven-storey and three of ten-storey apartment blocks) (Σούτος, 1983: 106) (Map 3). The housing estates of the second period were constructed during the dictatorship (Map 4).

The Germanika shacks were the last to be demolished in the area. Their demolition took place from 1962–1964, and the construction of the apartment buildings followed during the period from 1969–1971 (Map 3). This housing estate was compromised of 19 apartment buildings (of six, seven and eleven storeys) (Map 4).

The apartments were given to beneficiaries for homeownership. However, the beneficiaries had to pay a small amount, equal to the construction cost, in order to become owners of their dwelling.

Map 4: Number of storeys per apartment building in the Tavros social housing estates

Redevelopment of a building block (BB 1Γ) in Tavros

In the late 1980s, the redevelopment [5] oof the eight apartment buildings was implemented, which constituted the old stock of housing estates in Tavros (Figure 6b). This was done by the Public Enterprise of Town Planning and Housing (DEPOS) in cooperation with the Municipality of Tavros (the two agencies formed a consortium). The regeneration of these apartment buildings in Tavros constituted DEPOS’s largest scale social project [6] (Βαρελίδης, 2001: 24).

The project began as a request made by the Tavros Municipality to DEPOS for two basic reasons: 1) this area was the most degraded in the area and had severe social problems (i.e. cases of domestic violence), and 2) the income of the homeowners was low; thus, they were financially unable to maintain and upgrade their individual apartments and the whole estate collectively. The residents consented to the project implementation which was required for the beginning of the project (Λουκόπουλος, 1990: 34)

The younger residents who could financially afford to resettle to another area left and abandoned their apartments. As a result, those who continued to live in the apartment buildings were primarily those who either did not want to or could not leave for financial reasons (Βαρελίδης, 2001: 18). The need for the residents’ relocation was serious due to the inadequate conditions of the apartments of the old housing buildings. Thus, public intervention for the relocation was necessary (Βαρελίδης, 1999: 320).

The implementation of the redevelopment project faced several difficulties. The lack of previous experience, as well as a number of issues, such as the housing tenure, the negotiation method and the difficulty of working with the residents in a cooperative context, were the main issues that had to be dealt with by the consortium (Ρωμανός, 2000). The issues about housing tenure that had to be resolved were the large number of co-inheritors (approximately 300) who had to agree to the programme implementation, the residents who had not paid the price to the Ministry in order to be the owner of the apartment, the owners who lived abroad and the vacant apartments, amongst others. These issues were resolved through the creation of a housing association and cooperation between DEPOS and the municipality (Ρωμανός, 2000).

Another issue that had to be dealt with by the DEPOS and municipality consortium was the temporary housing of the owners until the regeneration project was completed. For that reason, the beneficiaries were given rent subsidies by the consortium (Βαρελίδης, 1999: 327).

Despite the problems that emerged, the regeneration of this area with the old housing stock in Tavros, in comparison with the rest of DEPOS reconstruction programmes, ‘achieved greater success’ (Ρωμανός, 2000: 199). The success had to do with the fact that the area of the old stock was radically upgraded, additional residential space was given to the beneficiaries and the two agencies (DEPOS and the Tavros municipality) successfully cooperated (op., 199).

Ultimately, an estate with eight new apartment buildings was constructed (six and seven storeys) with 144 dwellings for the housing rehabilitation of the homeowners of the old housing estate (Figure 7). Five different types of dwellings – according to the size of the apartments (from 67–102 m2) – were given to the beneficiaries. The apartments of 67 m2 were given free of charge. However, for the larger apartments, the beneficiaries had to pay a price (lower than the cost of construction) (ΔΕΠΟΣ-Βαρουτσής, 1990: 71-72). The allocation of the apartments to beneficiaries was implemented by a lottery. However, they could choose an apartment according to their needs (Βαρελίδης, 2001: 22-23).

The apartment buildings that were constructed constituted the penultimate social housing estate that was built in the area [7] (Figure 8). In fact, in 1991, the construction of the eight apartment buildings was completed, and the apartments were ceded to the beneficiaries. Some of these apartments were used as stores. The regeneration project included the construction of the School of Public Administration, which was completed in 1996. The purpose of the construction of this school and the stores was to cover the cost of the project (Ρωμανός, 2000).

Figure 8: Part of the social housing estate in the building block (on the left side, the School of Public Administration)

The neighbourhood today

In recent years, new residents, either Greeks from other parts of the country or immigrants from other countries, have settled in the neighbourhood. Today, the new residents of Tavros buy or rent an apartment in the social housing estates. The changes in the neighbourhood’s population composition occurred mainly after the mid-1990s when most beneficiary families had repaid their debt to the Ministry of Welfare and could then transfer or sell their dwelling. However, the influx of immigrants has not been as heavy as some residents of the neighbourhood believe it to be. More specifically, according to the 2011 census, 12.9% of the population were immigrants from developing countries. This proportion is slightly higher than that of the wider area [8] (11.5%), but it is much higher compared with Moschato-Tavros municipality. In 1991 and 2001, the difference between the social housing estates and the wider area was approximately the same, although the rates were much lower (ΕΚΚΕ-ΕΛΣΤΑΤ, 2015).

Despite the influx of new residents, in recent years, many third- and fourth-generation descendants of the first residents (Asia Minor refugees and internal migrants) have continued to dwell in the neighbourhood. Some have never lived in a different neighbourhood [9], while others had moved to other areas but then returned to Tavros. Recently, the descendants of the beneficiaries of the Ministry of Welfare returned to Tavros and, more specifically, to the apartment they inherited from their parents or grandparents.

The residential and urban development of the neighbourhood, therefore, differs from that of the wider area. However, the residents’ social characteristics do not differ that much (Table 1), as is the case of the working class’s traditional suburbs of Western Athens, with the exception of professionals and higher education graduates (the percentage is lower in the social housing estate in Tavros) (Kandylis et al., 2018: 91). Yet, the difference is slightly greater concerning the social characteristics of the residents in the social housing estates than in the municipality of Moschato-Tavros. For example, as shown in Table 1, the percentages of unskilled workers (category 9 of ELSTAT), people living in disadvantaged housing conditions (in dwellings up to 15 m2 per person without insulation and without heating) and immigrants from developing countries are higher in Tavros’s social housing estates than in the whole municipality. In contrast, the percentage of professionals, higher education graduates, secondary education graduates and professionals is much lower in Tavros’s social housing than in the municipality as a whole.

Table 1: Comparison of the socio-demographic data of Tavros social housing in relation to its wider areas

In conclusion, the social housing estates in Tavros – which were built for the housing rehabilitation of refugees and internal migrants – constitute a residential and urban unit that differs greatly from its wider area concerning the morphological characteristics of their apartment blocks. The housing estates’ apartment buildings are mostly four-storey buildings (however, there are a few three-storey and high-rise buildings) arranged in a way to provide adequate sunlight and natural ventilation. The area was planned from the beginning with the creation of the social housing estates and there was a provision for the creation of vacant spaces between the buildings. However, the differences are less significant in terms of the social characteristics of the inhabitants.

This paper is based on the qualitative research with residents of the neighbourhood that the writer carried out from April 2016 to May 2017 in the context of her PhD thesis at Harokopio University. The thesis is entitled ‘Social housing in Athens. Study of the refugee settlements Dourgouti and Tavros from 1922 until today’.

[1] Tavros was an autonomous municipality from 1943 to 2010. However, in 2010, in the context of Kallikratis Plan, Tavros was merged with Moschato. Hence, Tavros became part of the wider municipality of Moschato-Tavros (FEK 87Α/ 07.06.2010).

[2] The name ‘Nea Sfageia’ (‘New Slaughterhouses’) originates from the place -within walking distance of the refugee’s residences – where the animals were slaughtered. The Tavros municipal slaughterhouses existed from 1916 until 1968 when they were closed. They were called ‘Nea Sfageia’ because there was already an area that was called ‘Palaia (Old) Sfageia’ in Kallithea (Σούτος, 1983: 230).

[3] In this area, a housing cooperative was established in order to divide a large piece of land and convert it to plots. Those 55 plots were conceded to beneficiary refugees who were responsible for the construction of the residence.

[4] Also, there were internal immigrants who could afford to settle in the wider area of Tavros either by renting, buying their own home or by building it with their own means.

[5] However, this redevelopment project involved only one building block. Also, the number of the beneficiary families was small (136 families, most with four members).

[6] The largest project compared with those at Nea Philadelphia and Kaisariani.

[7] In 1998, the Workers’ Housing Organization constructed a social housing estate of three apartment blocks in Tavros.

[8] This is defined as the surrounding area without social housing estates.

[9]According to the 2011 census data, 57.7% of Tavros social housing estate residents never lived in a different settlement from that of the study area (ΕΚΚΕ-ΕΛΣΤΑΤ, 2015).

Entry citation

Myofa, N. (2020) Neighbourhood of social housing estates in Tavros, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/social-housing-in-tavros/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.97

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Βαρελίδης Γ (2001) Κοινωνικές και επιχειρησιακές συνιστώσες της οικιστικής ανάπλασης στο Ο.Τ. 1Γ στον Ταύρο. Επιστημονική Επετηρίδα Εφαρμοσμένης Έρευνας 6(1): 17–37.

- Βαρελίδης Γ (1987) Νέοι Τρόποι Οικιστικής Ανάπτυξης. Το παράδειγμα της Ανάπλασης στον Ταύρο. Hellenews. Αθήνα.

- Βαρελίδης Γ (1999) Προτεινόμενο πλαίσιο οικιστικών αναπλάσεων στον αστικό και περιαστικό ελλαδικό χώρο. Κοινωνικές, θεσμικές, επιχειρησιακές, πολεοδομικές συνιστώσες. Εθνικό Μετσόβιο Πολυτεχνείο (ΕΜΠ).

- ΔΕΠΟΣ και Βαρουτσής Σ (1990) Σχεδιασμός αναπλάσεων-Συγκεκριμένα παραδείγματα (Ταύρος). Τεχνικά Χρονικά 4: 71–74. Available at: http://library.tee.gr/digital/techr/1990/techrpdf.

- Ελευθερουδάκης Κ (1931) Ταύρος. Τόμος 12ος. Αθήνα: Ελευθερουδάκης.

- ΕΛΣΤΑΤ – ΕΚΚΕ (2015) Πανόραμα Απογραφικών Δεδομένων 1991-2011. Available at: https://panorama.statistics.gr/.

- Λουκόπουλος Δ, Πολύζος Ι, Πυργιώτης Γ, κ.ά. (1990) Δυνατότητες και προοπτικές των προγραμμάτων ανάπλασης. Προτάσεις για ένα νέο οργανωτικό σχήμα. ΕΜΠ Τομέας. Αθήνα: ΕΜΠ.

- Μυωφά Ν (2019) Κοινωνική κατοικία στην Αθήνα. Μελέτη των προσφυγικών συνοικισμών Δουργουτίου και Ταύρου από το 1922 έως σήμερα. Χαροκόπειο Πανεπιστήμιο.

- Παπαδοπούλου Ε και Σαρηγιάννης Γ (2006) Συνοπτική έκθεση για τις προσφυγικές περιοχές του Λεκανοπεδίου Αθηνών. Αθήνα: ΕΜΠ – Σχολή Αρχιτεκτόνων Μηχανικών Τομέας Πολεοδομίας Χωροταξίας – Σπουδαστήριο Πολεοδομικών Ερευνών.

- Ρωμανός Α (2000) Ανάπλαση προσφυγικών κατοικιών στο Δήμο Ταύρου από τη ΔΕΠΟΣ. In: Καλογήρου Ν (επιμ.) Δημόσια Αρχιτεκτονική. Αθήνα: Μαλλιάρης Παιδεία, σσ 198–207.

- Σούτος Δ (1983) Δήμος Ταύρου. Σελίδες από την Ιστορία του. Αθήνα: Λόγος και Αντίλογος.

- ΦΕΚ 87Α/07.06.2010 (2010) Νέα Αρχιτεκτονική της Αυτοδιοίκησης και της Αποκεντρωμένης Διοίκησης − Πρόγραμμα Καλλικράτης. Ελλάδα.

- Maloutas T, Kandylis G and Myofa N (2018) Exceptional social housing in a residual welfare state: Housing estates in Athens. In: Baldwin Hess D, Tammaru T, and van Ham M (eds) Housing Estates in Europe: Poverty, Ethnic Segregation, and Policy Challenges. Springer, pp. 77–98.