The capital’s social and professional stratification, 1860-1940

Bournova Eugenia|Dimitropoulou Myrto

History, Social Structure

2015 | Dec

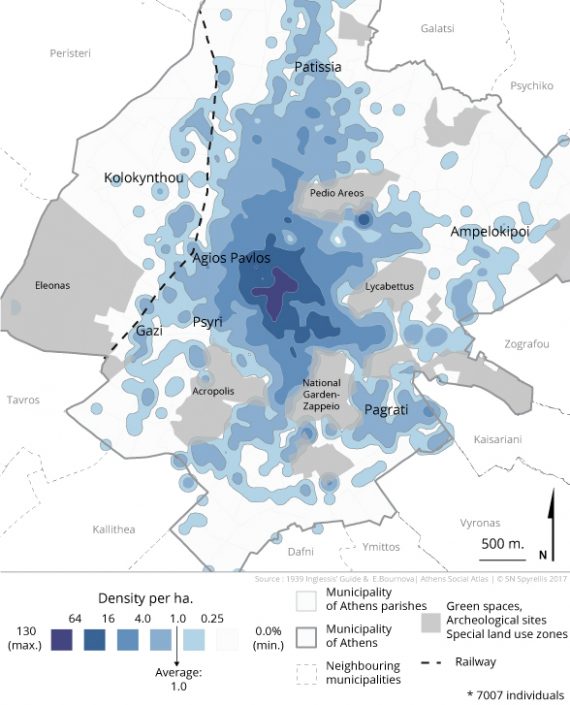

The size and population density of the capital

Population density has remained quite low between 1860 and 1940: 172 individuals per hectare in 1879 and only 91 per hectare in 1907. The low density of 1907 is due to the fact that the size of the urban area increased fivefold, as sparsely populated “rural” areas were included in it. Right before the war, population density increased but still remained very low -at 127 individuals per hectare in 1940.

Graph 1: Population growth in Athens, 1834 – 1951

Source: Population censuses in the respective years

Table 1: Social and professional stratification in the capital, 1860-1910 (%)

Source: Municipality of Athens Population Registrar, and N. Igglessis, 1910.

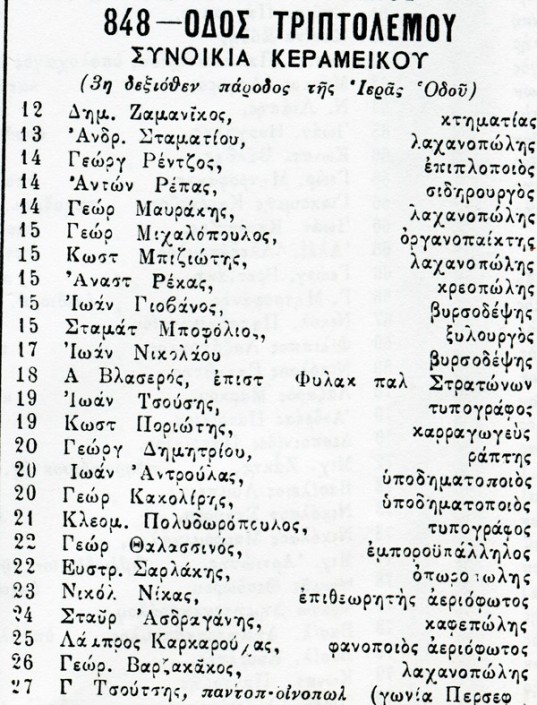

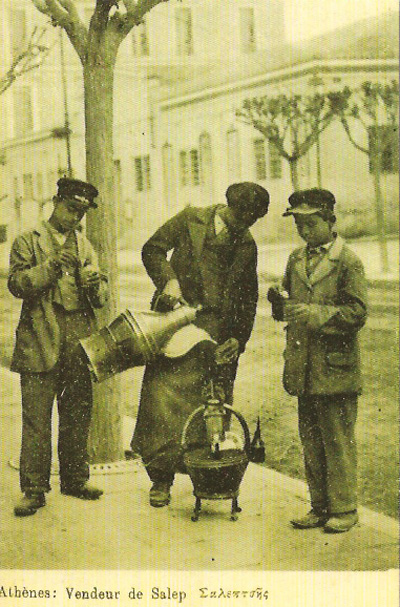

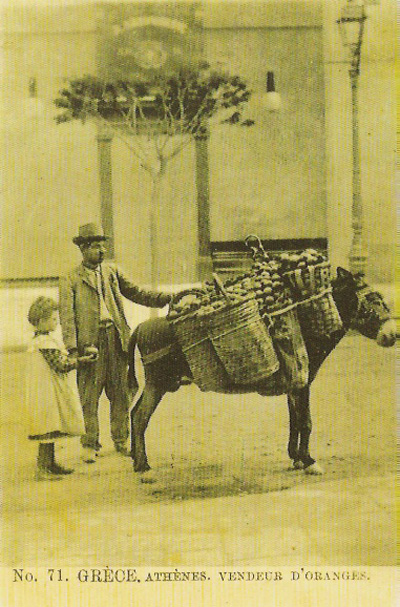

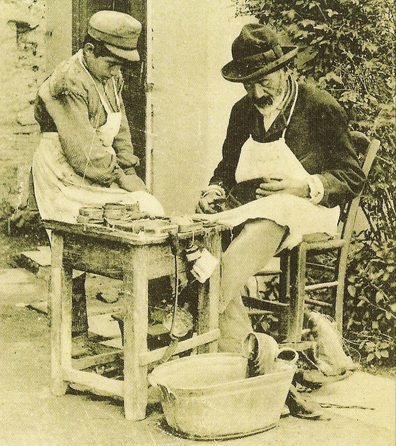

In the second half of the 19th century and in the early 20th century, Athens was a town of craftsmen, craft industries and small-scale trade: this is the clear picture that emerged from analysing death certificates in the Municipality of Athens. In addition, the distribution shown in N. Inglessis’ 1910 commercial Guide [1] – a door-to-door recording of professionals in Athens – confirms the important role of merchants, artisans and craftsmen, though it excludes a significant part of the working classes, such as unskilled manual workers .

In the following period, up to 1940, approximately 150,000 refugees moved to the municipality, inflating the capital’s working class. However, the social and professional composition of the population on the eve of World War II is not known, since 1928 is the last year for which census data is available. N. Igglessis’ 1930 commercial Guide was limited to professionals who occupied business premises (hence it did not record employees, public and private sector staff and workers). It provides an image of a city with a large middle class, mainly consisting of shop owners, restaurateurs, real estate agents, hoteliers, contractors, insurance agents and craftsmen, with a significant presence of higher-ranking freelance professions.

Table 2: Social-professional classification of professions in Athens, as recorded in N. Igglessis’ 1939 Commercial Guide

Source: N. Igglessis, 1939

Housing choices and the mapping of social groups

Available data for the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, show very limited social segregation. The coexistence of social strata is due to the relatively small area of the capital, whose land uses had not yet been finalised. Thus, the working class was not excluded from the city centre, which gathered most administrative, economic and cultural activities and is where the elite chose to live.

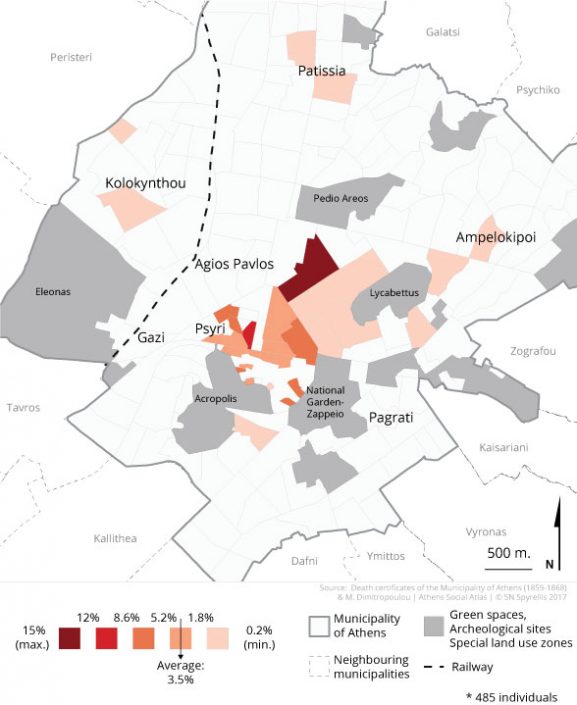

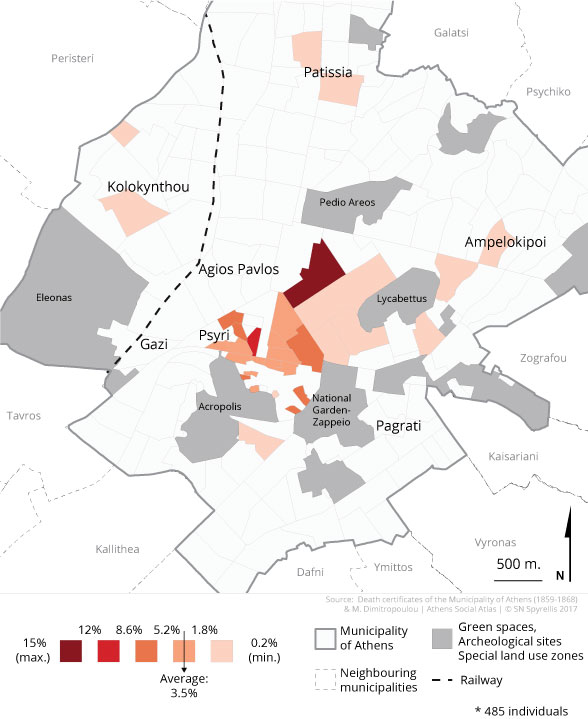

Map 1: Percentage (%) of lower occupational categories in the active population by parish in the Municipality of Athens (1859-1868)

In the 1860s [2] the working class mainly lived in the outskirts of the new city (Map 1): the settlement of Exarchia (Zoodohos Pigi parish) and a part of the neighbourhood of Psirri, mainly in the parish of Aghios Dimitrios but also in Aghioi Anargyri. Seven other areas , all of which today are part of the capital’s urban core, have significant concentrations of working class residents. Specifically, five of them were city fringe areas at one point, while two are located at the foot of the Acropolis. These are the parishes of Karytsi, Aghios Philippos, Metamorphosi Sotiros, Aghia Aikaterini and Aghioi Apostoloi. Two more parishes are those of the Romvi and Monastiraki areas.

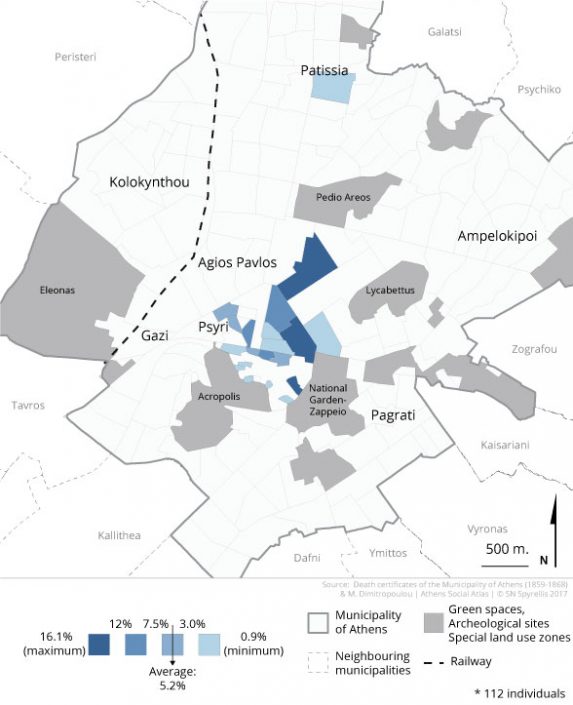

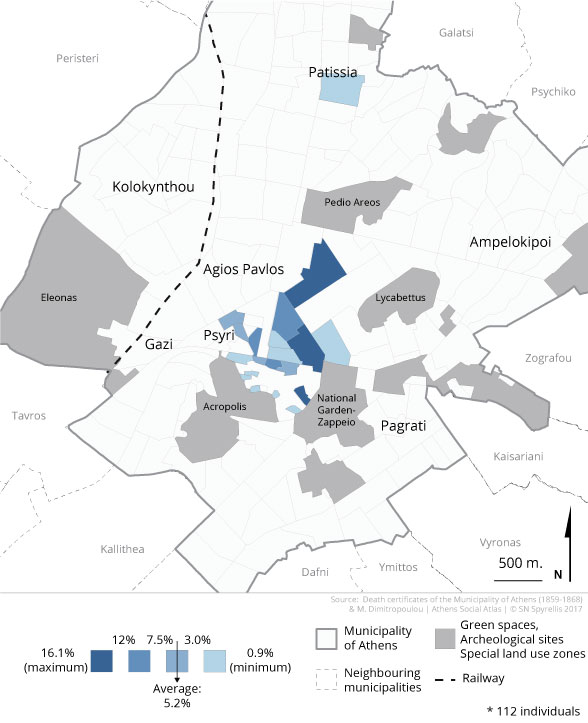

Map 2: Percentage (%) of upper occupational categories in the active population by parish in the Municipality of Athens (1859-1868)

The affluent strata (Map 2) mostly resided in the parishes of Agios Georgios Karytsi and Metamorfosi Sotiros, as well as in Exarchia. The first is close to the University, the Magistrate’s Court, the National Bank and borders with the city’s boulevard, Panepistimiou Street, to the east. The second one is very close to the Palace, the Royal Gardens and Syntagma Square. The elite had a significant presence in other parts of the old city, in the parish of Romvi , next to the Cathedral and in close proximity to three ministries: Ermou Street number 11 was where the Ministry of Justice was located while the Ministry of Religion & Public Education was located in nr 81. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs was located at the intersection of Mitropoleos and Nikis streets. In addition, concentrations of upper strata were recorded in the parish of Agioi Theodoroi, the area where the first Palace, the National Bank and other institutions of the time were located. Agioi Theodoroi borders on two major roads, Panepistimiou Avenue and Athinas Street, as well as on Omonia Square and the commercial district of Psirri (Agioi Anargyroi and Agios Dimitrios).

The segregation of social classes was not very sharp and the upper class coexisted with working class. However, the parishes on both sides of the western part of Ermou Street and the ones at the foot of the Acropolis, were exclusively inhabited by poorer strata.

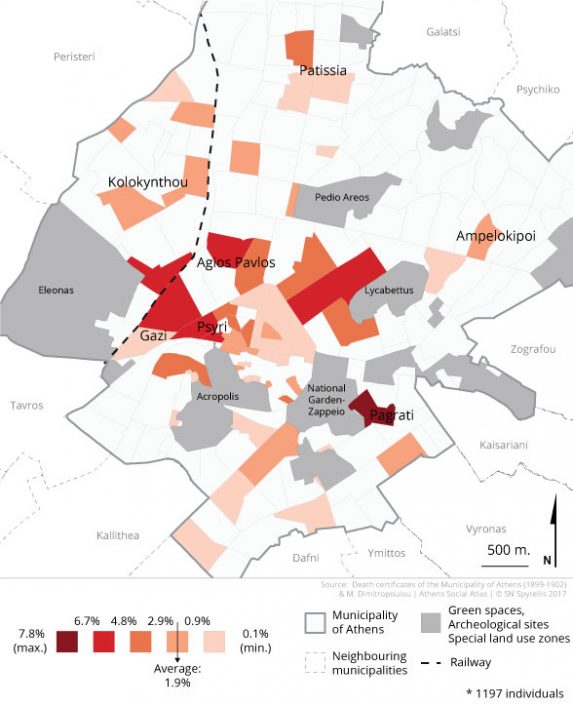

In the beginning of the 20th century, the city area had grown seven-fold, while its population was four times larger than in 1860. According to the death certificates for the years 1899-1902 [3] the working class (Map 3) seemed to gradually abandon the historic city centre and to spread out in all directions, preferring areas outside the old city limits. All areas with the highest rates of working class residents in 1900 did not appear on the map of the previous period. The only parish still largely inhabited by the working class was the parish of Agia Aikaterini, home to many coachmen and tram employees. This makes sense, as the parish bordered Amalias avenue, from where tram lines to Faliron passed, while Zappeion, the terminus for trams from Omonia Square, was situated nearby.

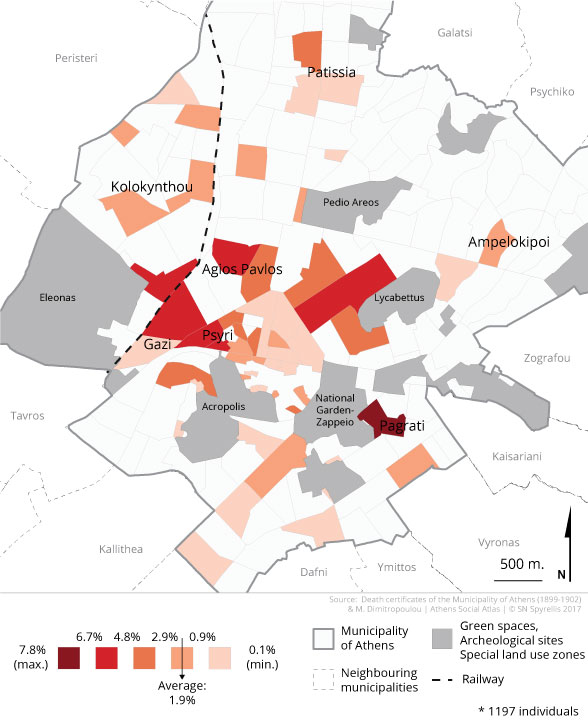

Map 3: Percentage (%) of lower occupational categories in the active population by parish in the Municipality of Athens (1899-1902)

The working class dominated the remote parish of Agios Spyridon, in what today is the neighbourhood of Pangrati, which was annexed to the city plan for the first time in 1886. The area was clearly separated from the rest of the city by the Palace’s gardens and Zappeion, while the Ilissos river marked its natural boundaries. A second area attracting the working class lied in the western part of the city. It was the area of Kerameikos (between the terminus of Thisseion and Pireos street, near the Gas plant) as well as the farming area of Profitis Daniil. The third working class area lied in the northern part of the city, in the areas of Agios Pavlos and Agios Konstantinos -in Vathi-, directly adjacent to Metaxourgeion, the capital’s production zone, which hosted large-scale workshops. Further in the north, the agricultural zone of Patissia attracted a significant number of gardeners and workers.

Finally, it is important to mention the (limited) presence of the working class in the neighbourhood of Neapolis, where, according to an anonymous journalist of the Economic Review, a core of workers’ buildings had already been built in 1873. “Workers have the natural tendency to acquire real estate property. This is a sufficiently developed economic phenomenon in Greece, as arbitrarily proven by buildings that mainly belong to workers, situated next to Ilissos river and between Lycabetus Hill and Pinakotes” [4].

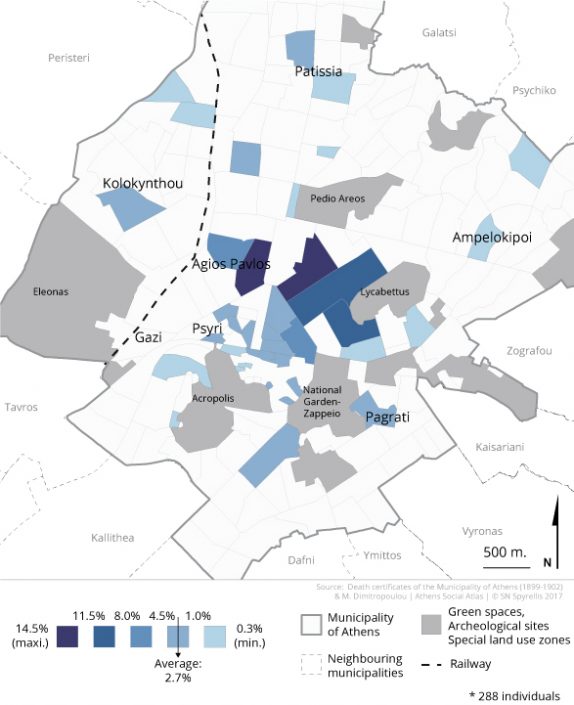

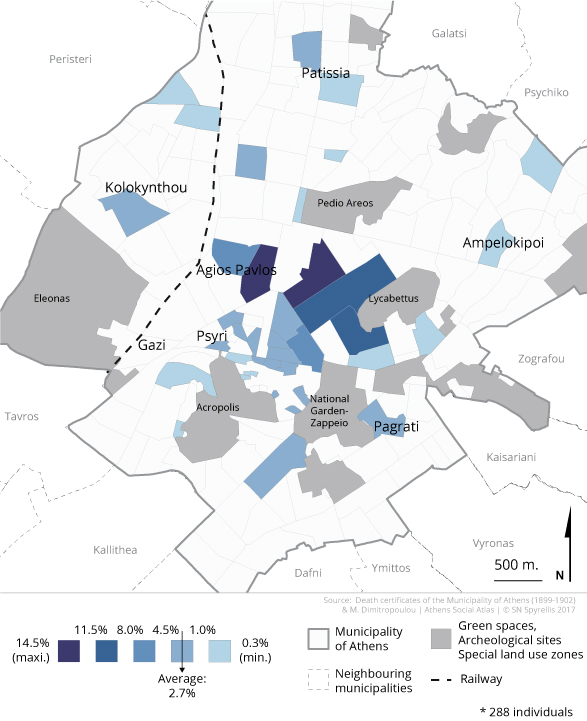

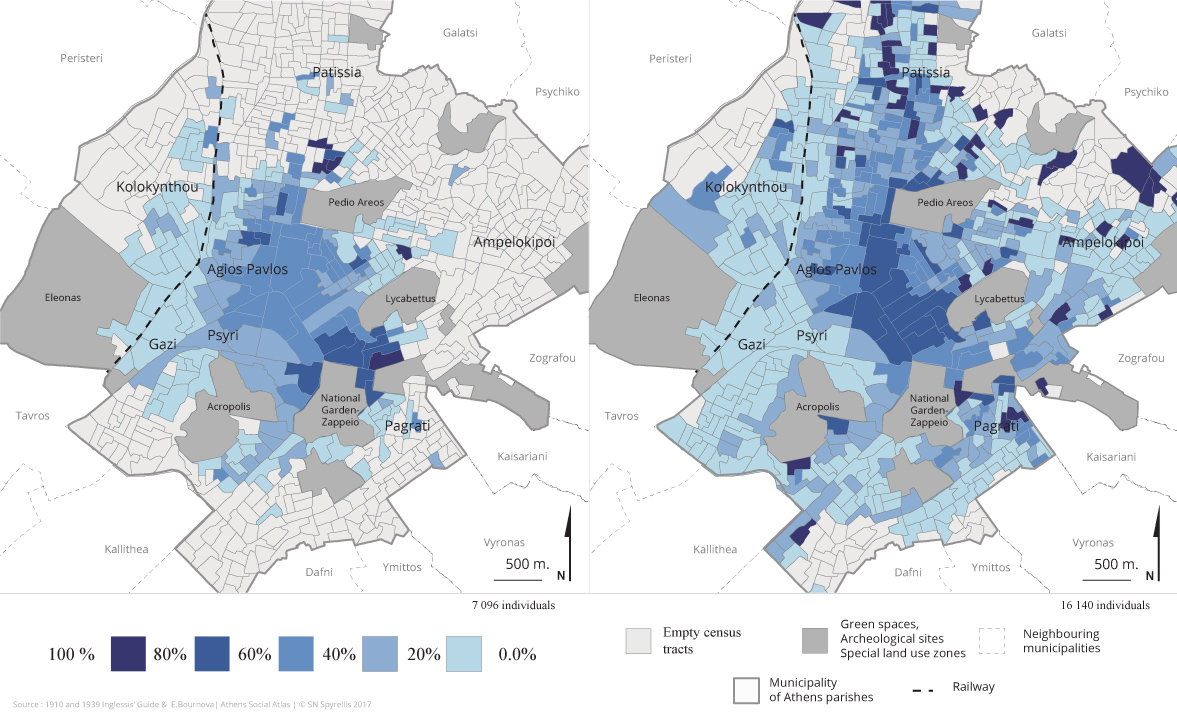

Although the coexistence of working and upper classes continued, it seems that the elite also distanced itself from the capital’s commercial centre, with a clear tendency to move to north and north-eastern neighbourhoods, while remaining within the city limits (Map 4). The Athenian elite primarily lived in the Agios Konstantinos -Vathi- area, which, as we saw, was popular with the poorer classes. The second option is the neighbouring settlement of Exarcheia. These were two new areas, close to Omonia Square and the Athens Technical University, but also to the capital’s economic and administrative centre. Furthermore, the upper class gathered around Kolonaki -which in the coming decades evolved to become the capital’s beau quartier– as well as in Neapolis.

Map 4: Percentage (%) of upper occupational categories in the active population by parish in the Municipality of Athens (1899-1902)

The poorer strata left the centre of Athens in clearly greater rates than the elite. As is the case in many other European capitals, the Athenian elite chose to remain in the city centre, which concentrated all economic and administrative activities. Psychiko -the first suburb based on the design of British garden cities- in the north of Athens but at a short distance from the centre, was created in the 1930s.

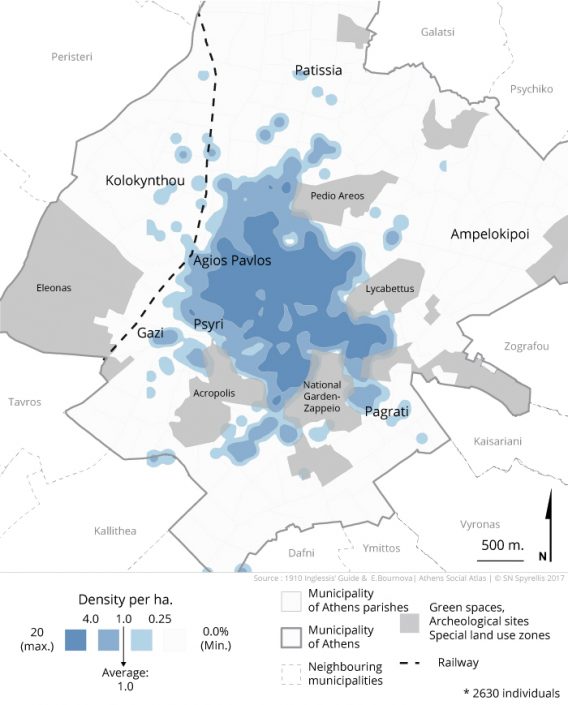

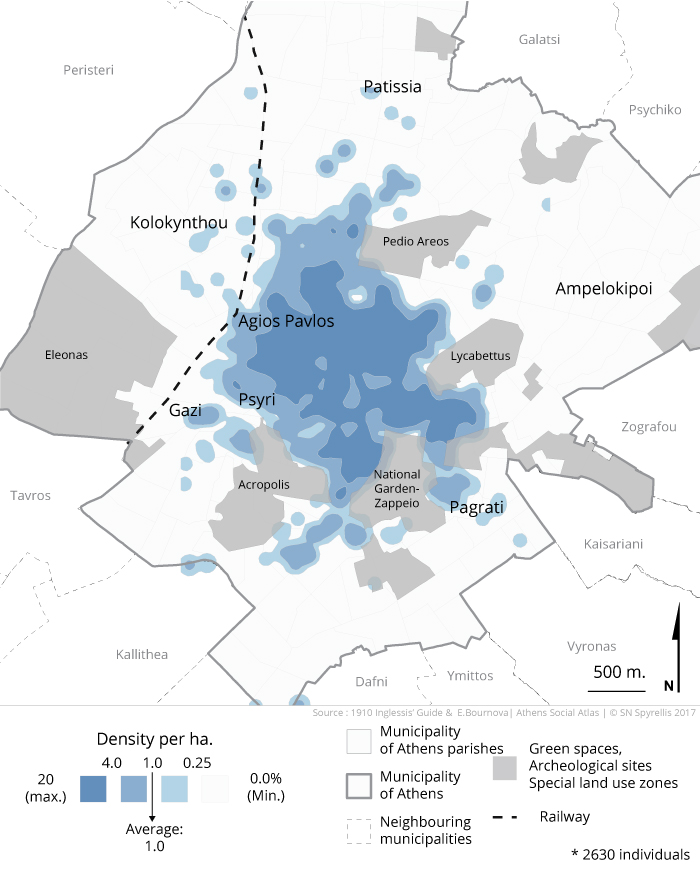

Map 5: Concentration of upper occupational categories in the Municipality of Athens (1910)

The mapping of the data available in N. Igglessis’ 1910 commercial Guide [5] confirms that the elite lived in the city centre, but with a preference for the east side, though also extending to the North. The upper class mostly lived around the Royal Garden, north and north-west of it through Kolonaki to Lycabettus Hill, and north of Omonia square, as in the previous century. A new small core also appeared in Kypseli. The 740 lawyers recorded in 1910 were scattered throughout the centre but preferred Ippokratous, Zoodochou Pigis and Solonos streets, that were close to the courts, which were located at the corner of Stadiou Street and Santarosa Street close to Omonia square). Lawyers also located in Pireos, Menandrou, Deligiorgi and Sophocleous streets, next to the banks and the stock market. The 12 catalogued shipowners were mainly located around the Palace and Syntagma square as well as in Patission Str, close to Omonoia. Most of the city’s 470 doctors were based in central streets of the city, around Syntagma and Omonia squares, where the “private clinics” of the time were located. The 45 dentists mostly worked around Syntagma Square, at a short distance from the Dental School, which was housed in 35 Mitropoleos str. University professors resided in the streets around the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, while professors of the National Technical University lived around that institution too. The city’s 230 engineers were more dispersed, since they did not appear to have specific preferences for streets or neighbourhoods. Athens’ 40 notaries were also located in the city centre, around Plaka, the City Hall and Omonia Square as well as in the district of Agios Constantinos – Kyklovorou. The city’s approximately 70 MPs mainly lived near the (Old) Parliament building, i.e. in Kolonaki, Syntagma and Omonia.

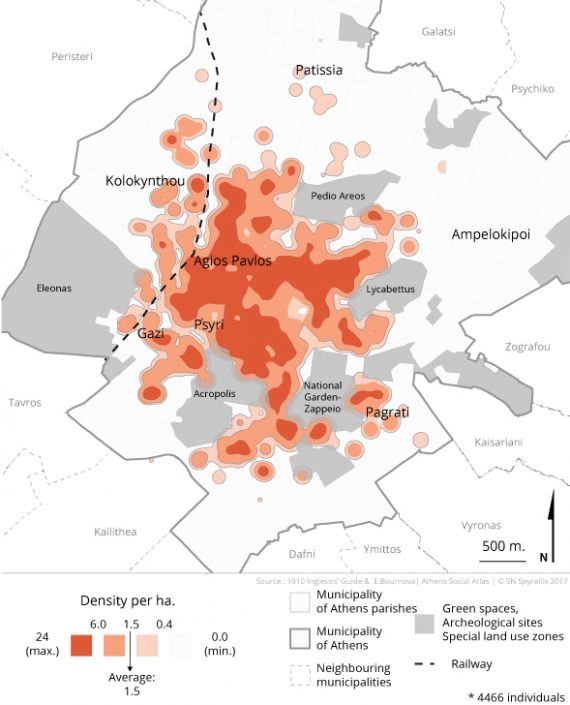

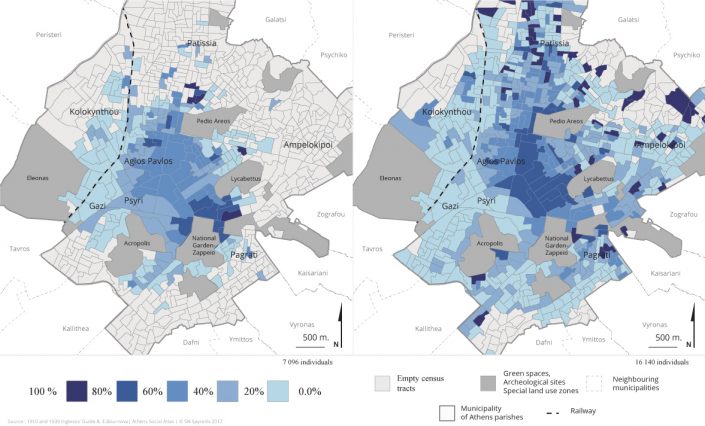

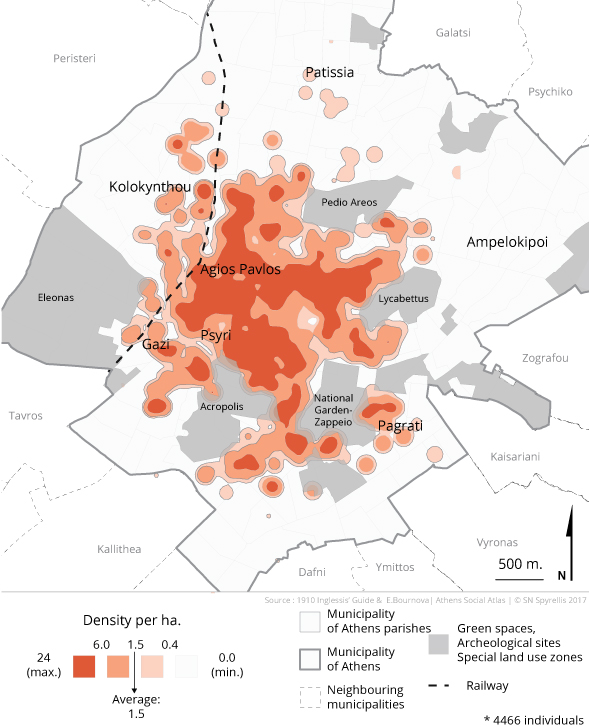

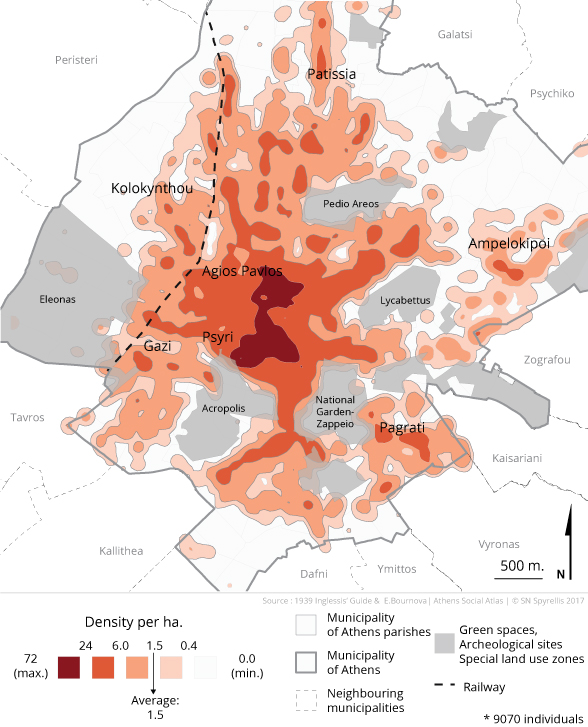

Maps 6: Concentration of lower occupational categories in the Municipality of Athens (1910)

On the other hand, although labourers and private employees were only partially recorded in the commercial Guide, we can safely claim that the working class was spread across the capital and coexisted with the upper strata albeit with a preference for the historic centre. The working class includes 1,048 gentlemen’s tailors, and the personnel of 947 coffee houses “without a telephone” and 628 haberdashery shops, scattered throughout the city in order to cover the needs of residents in every neighbourhood, though most of them concentrated in the city centre.

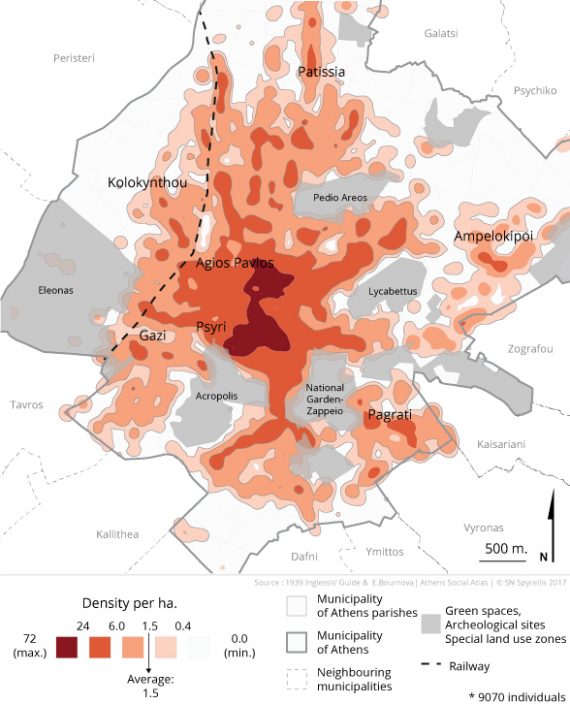

Maps 7: Concentration of lower occupational categories in the Municipality of Athens (1939)

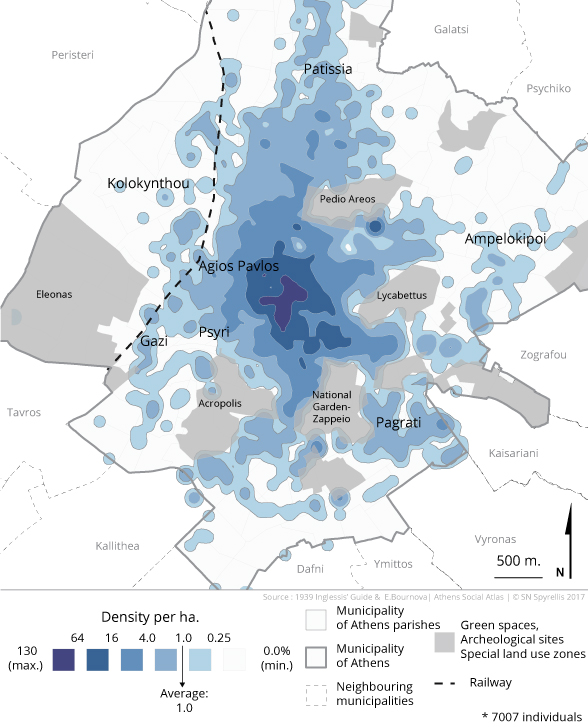

On the eve of World War II, we note the beginnings of spatial segregation. There is a general tendency for concentration towards the west for the working class and towards the east and north for the elite. However, the urban extensions of the time into the city’s more remote areas, which were annexed to the city plan after 1920 were inhabited by both the upper class and the working class. , This was when the agricultural area of Patissia became urbanised.

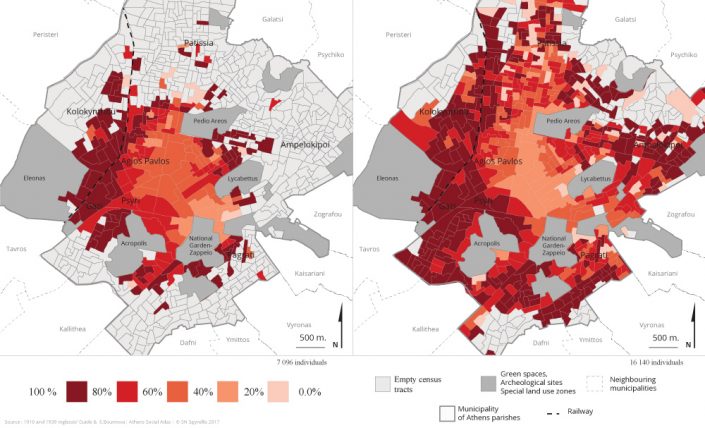

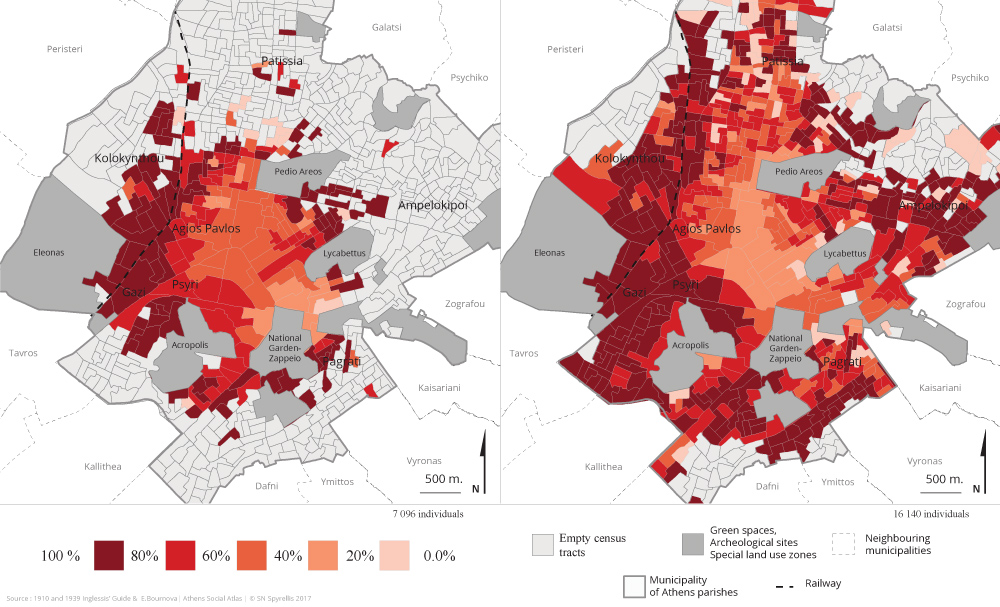

Maps 8 & 9: Percentage of lower occupational categories in the active population by parish in the Municipality of Athens (1910 and 1939)

In particular, in 1940, Pangrati becomes urbanised. Lawyers, engineers and doctors, along with shipowners, bankers and other representatives of the social and economic elite, prefer the eastern areas of the capital’s central zone, in addition to Kolonaki and the Museum,and maintain country houses in Patissia, thereby increasing the proportion of the elite in the north of the city. Only four engineers, bearing the surname Georgopoulos, were registered under the same address, 236 Patission Str in 1939. They were probably co-located members of the same family. The only exception is the presence of the elite in the area south of the Acropolis, in particular around Dionysiou Areopagitou Street.

Map 10: Concentration of upper occupational categories in the Municipality of Athens (1939)

Maps 11 & 12: Percentage of upper occupational categories in the active population by parish in the Municipality of Athens (1910 and 1939)

Οι πολεμικές συγκρούσεις που ακολούθησαν και οι όποιες κοινωνικές ανακατατάξεις προέκυψαν μεταπολεμικά, δεν ανέτρεψαν την τάση αυτή.

[1] Inglessis’ Guides are kept in the Library of the Commercial and Industrial Chamber of Athens. They were published from 1905 until 1957.

[2] For the 1859-1868 period, the data for the working and the upper class are based on 485 and 112 death certificates respectively, obtained from the Municipality of Athens.

[3] For the 1899-1902 period, results are based on 1197 death certificates for working class individuals from the Municipality of Athens and 288 death certificates for individuals who belonged to the upper social strata.

[4] “Labour settlements” Economic Review, Year I, Sheet VII , September 1873.

[5] Despite the fact that the author of the Guide does not follow a specific methodology, he is probably based on the records of the 1907 census. Thus, an important part of the male working population is recorded [more than 26%]: a total of 94,000 men were registered in the capital in 1907, of which 67,500 were older than 15 years, while the Guide listed 17,640 men who either had a profession or were pensioners. It seems that unskilled workers were only registered in exceptional cases. Women were recorded only if they had a specific profession, though widows or ladies without reference to a specific profession were recorded. For individual studies concerning the economic and social history of Athens in the period 1860 – 1960 see http://www.social-history-of-modern-athens.gr/el/

Entry citation

Bournova, E., Dimitropoulou, M. (2015) The capital’s social and professional stratification, 1860-1940, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/social-stratification-1860-1940/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.53

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Ποταμιάνος Ν (2011) Η παραδοσιακή μικροαστική τάξη της Αθήνας : μαγαζάτορες και βιοτέχνες 1880-1925. Πανεπιστήµιο Κρήτης. Available from: http://elocus.lib.uoc.gr/dlib/6/f/8/metadata-dlib-1330425501-380121-25886.tkl#.

- Χατζηιωάννου Μ-Χ και Αγριαντώνη Χ (1995) Το Μεταξουργείο της Αθήνας. Χατζηιωάννου Μ-Χ, Ζιούλας Χ, Παπανικολάου – Κρίστενσεν Α, κ.ά. (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Κέντρο Νεοελληνικών Ερευνών Εθνικό Ίδρυμα Ερευνών (ΚΝΕ – ΕΙΕ). Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10442/7739.

- Bournova E and Garden M (2014) Naître à Athènes dans la première moitié du xxe siècle. Démographie et institutions. In: Annales de démographie historique, CONF, Belin, pp. 209–230.

- Dimitropoulou M (2008) Athènes au XIXe siècle : de la bourgade à la capitale. Université Lumière, Lyon II.