Contesting the Crisis: Cooperative/ Social Economy and Solidarity or Charity?

Arampatzi Athina

Politics, Social economy

2015 | Dec

I don’t believe in charity. I believe in solidarity.

Charity is so vertical. It goes from the top to the bottom.

Solidarity is horizontal. It respects the other person.

I have a lot to learn from other people.Eduardo Galeano

In the light of the global crisis, national governments across Europe have actively engaged in the process of promoting austerity agendas, fiscal retrenchment and massive reductions in social welfare. Austerity politics and their outcomes in the Greek context reveal how this devolution of financial burdens has acted as a strategic displacement of responsibility, essentially being about “making others pay the price of fiscal retrenchment” (Peck 2012). Cities in Europe, and Athens in particular, have absorbed the ‘trickle-down’ effects of austerity politics, impacting primarily on the working and middle classes of the city’s population. In this regard, austerity urbanism, through budgetary cuts in public services, entrepreneurial and privatization policies, coupled with rising unemployment and homelessness has rendered Athens a “staging ground for fiscal revanchism” (Peck 2012).

The above have had a severe impact on the social reproduction of already vulnerable and precarious social groups, unemployed, homeless and the new marginalized by austerity politics. The collapse of social welfare and provision, public services and key institutions, such as the health and education national systems, has further precipitated civil society responses. These often involve practices of assisting the ones in need, through food, medical supplies and goods collection and distribution, soup kitchens, fundraisers through social and public events and exchanges of goods and services which bypass the intermediary use of money. While these are often interpreted through a de-politicized normative rhetoric around charity, as a humanistic universal approach to ‘those in need’, I argue here for a more critical understanding of these practices, one which seeks to question them on the basis of their politics.

Therefore, a conceptual distinction between ‘charity’ and ‘solidarity’ is crucial so as to discern between, on the one hand, ‘Greeks-only-soup kitchens’ organized by the Golden Dawn, food distribution by media and business corporations and, on the other hand, solidarity grassroots initiatives and structures. While charity signifies ‘a disembodied caring from a distance’ and support to ‘distant others’, solidarity is “a relation (emphasis added) which challenges forms of oppression” (Featherstone 2012). In this sense, the conceptual distinction is made based on the ways participants engage in these practices. On the one hand, charity practices objectify the passive recipients of support and, in this way, perpetuate uneven power relations and forms of oppression. On the other hand, solidarity as a relation constitutes a shared experience, which becomes the basis for cooperation among active participants. In turn, this type of collaboration holds the potential of social empowerment through political struggle, albeit not through a linear process.

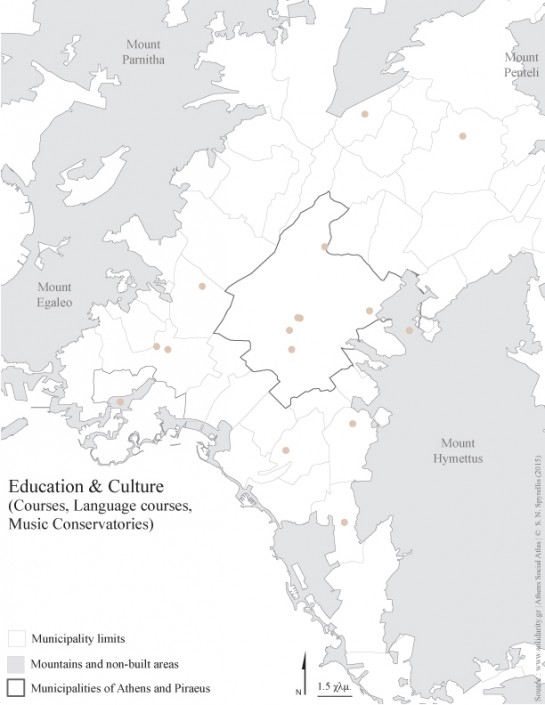

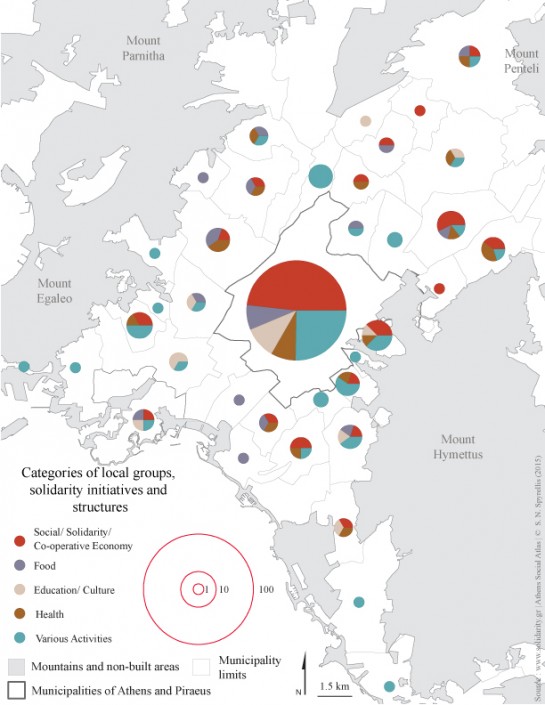

In regard to grassroots solidarity organizing, there are also differentiations among initiatives and groups across Athens and Greece, which seek to either, deal with impoverished social groups’ everyday basic needs or experiment with alternatives to austerity. The former category includes local initiatives, which gather and distribute food, clothes and basic goods, and social medical and pharmacy centers, which provide for immediate treatment for the unemployed, uninsured and migrants. The latter group includes experiments with alternative economies, such as barter markets and time banks, alternative currency exchanges, ‘without middlemen’ producers’ markets and cooperatives. These social and solidarity economy groups and cooperatives employ forms of economic activity and organization, for example the production and distribution of goods and the delivery of services, which are developed, sustained and controlled by the same participants involved in the activities (Wright 2010). Therefore, within this type of economic activity and organization, a decisive differentiation element from the dominant capitalist paradigm of production, goods’ marketing and service delivery, lies on the prioritization of the collective interests of participants and groups over surplus value extraction and profit-making. Also, they promote participatory decision-making, in-group discussion and collective accountability and, in this sense, strive to organize working relations horizontally.

Therefore, the above solidarity practices are developed through an alternative paradigm in regard to organizing a solidarity economy, while at the same time become ‘learning laboratories’ for the participants involved, acting as ‘transformative relations’ and ‘generative forces’ of political relations and spaces (Featherstone 2012). Solidarity initiatives and structures emerging across Athens and Greece have yet to develop into powerful actors, able to pose bottom-up challenges to reinforced neoliberalism and austerity politics. Even though quite often these initiatives and structures are faced with pragmatic obstacles and internal contradictions, their role so far in activating and mobilizing participants through collective action and mutual support practices is considered crucial in challenging the widespread fear dominating the public discourse and the ‘scapegoat’ tactics of xenophobic, fascist practices targeting precarious and marginalized social groups.

The above discussion draws on my PhD research and ethnographic fieldwork conducted in Athens, Greece between 2012 and 2013.

Entry citation

Arampatzi, A. (2015) Contesting the Crisis: Cooperative/ Social Economy and Solidarity or Charity?, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/solidarity-or-philanthropy/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.27

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Featherstone D (2012) Solidarity: Hidden histories and geographies of internationalism. 1st ed. London: Zed Books.

- Peck J (2012) Austerity urbanism. City, Routledge 16(6): 626–655. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2012.734071.

- Wright EO (2010) Envisioning real utopias. London: Verso London.