2017 | Feb

Introduction

Urban public space is a social construction, resulting from power relations on contrasting views and practices concerning its control and management. In this paper, I explore the ways public space is eventually produced through the tension among contrasting territorial productions in the squares of Exarcheia, Agios Panteleimonas and Syntagma. In this analysis, I use Kärrholm’s (2007, 2005) framework on the territorial production of space (table 1).

Table 1: Forms of territorial production (Kärrholm, 2007)

Deleuze and Guattari (1972, 1980) describe territory as a delimited area of control; a different reality dominates outside its borderlines. A territory operates as a device that produces a certain order in the form of an assemblage that brings together heterogeneous elements. Moreover, a territory produces identities that relate to processes of exclusion and inclusion through rules, signs and directions. Finally, a territory does not exclusively refer to physical space but also to invented domains, such as the domain of philosophy. Following the above, territorial production constitutes a process through which delimited areas of control are produced and established.

According to Kärrholm (2005), the manifestation of power relations in public space can be analyzed as a process of tensions among differentiated territorial productions in the form of associations, appropriations, strategies and tactics. Associations and appropriations constitute the unplanned consequences of established and regular practices and do not express intentional claims of control. Strategies and tactics, on the contrary, constitute intentional attempts of control over public space and express specific claims. Tactics constitute personal claims of control on behalf of specific groups and develop within physical space. On the contrary, strategies develop outside physical space and constitute impersonal, usually mediated, attempts of control in the form of rules and directions.

In this article, I analyse primary data originating from my PhD thesis, entitled ‘Public space as a field of urban struggle. Everyday life practices as the outcome of power relations’’ [1], at the Department of Urban and Regional Planning, School of Architecture, NTUA. My research was based upon an inductive, mixed methodological approach consisting of an ethnographic study (direct and participative observation, semi-structured and in depth interviews) and a survey comprising questionnaires addressed to a random sample of users in each square. Field research took place from May to September 2014, while additional observations were conducted in the Spring of 2015.

This article is not a brief presentation of the aforementioned thesis but rather an attempt to re-examine my data through the deployment of the territorial production framework. Thus, while in my PhD thesis I focus on interactions between key urban actors, in this article I also focus on the tensions and conflicts between different and often contrasting territorial productions.

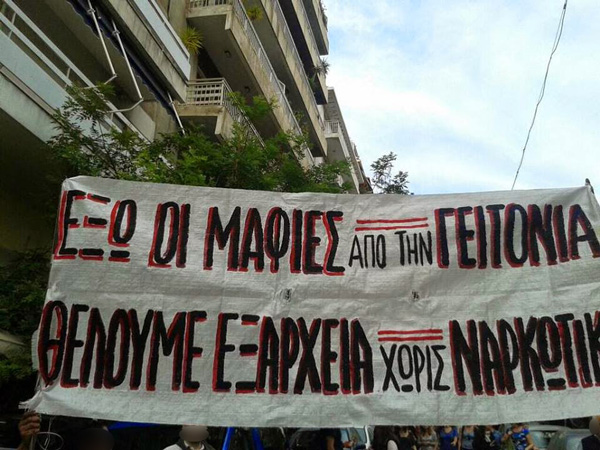

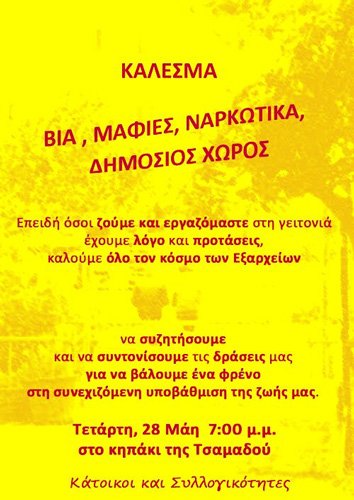

Exarcheia Square

Exarcheia Square is situated within the Exarcheia district neat the city centre, while the surrounding area hosts mixed land uses (residential, commercial and recreational). Two sets of established practices in the square and the broader district create the associations and appropriations upon which contemporary conflicts and power relations are developed [2].

Those sets include: 1) the use of the square by social movements and local political groups, due to the high density of social and political initiatives in the Exarcheia district and 2) the massive cannabis use in the square by its users and visitors.

Resulting consequences of the aforementioned sets of practices include: 1) the establishment of a ‘radical territory’ on the symbolic level, developed upon a strong symbolic cohesion among local movements, political groups, users of the square and part of local businesses, 2) regular appropriations from social movements and political groups and 3) everyday life associations concerning cannabis use and the emergence of the square as a place for cannabis purchase and use.

Along with these practices and territorial productions, ‘peripheral’ tactics have also been established. Those tactics are not developed by the aforementioned collective actors (local movements and political groups) and include regular clashes between groups of young people and the police outside any political context, attacks on political groups, degradation of the physical and cultural environment [3], and, finally, the establishment of aggressive groups that are related to drug dealing activities. The aforementioned territorial productions in total (associations, appropriations and peripheral tactics) are accompanied by further consequences that include the limited presence of institutional urban actors (the police, services of the Municipality of Athens) and the exclusion of large parts of district’s residents, such as children, families and the elderly, from the square.

Conditions of exclusion, as portrayed above, constitute the base upon contemporary conflicts have emerged and are the results of two territorial productions, namely the associations, related to cannabis use on the behalf of large part of the square’s users and visitors and the exclusionary tactics developed by local aggressive groups. Those groups, in an attempt to establish themselves and legitimize their presence, attempt to exploit the symbolic cohesion within the district and present themselves as a part of the local movement with, which, however, have no actual ties. Moreover, those groups move on violent attacks against residents, visitors and participants in local movements.

| “One cannot cross through the square, to sit there. Thus, the square instantly turns into a place that is used only by certain people. Additionally, the issue with the mafia, beside drug dealing is… that at the same time there is a great amount of violence. Violence between the dealers, against the residents, when someone asks them to leave there is actual physical violence, not verbal. We have noticed that there are connections with the schools, they exploit the economic crisis, families survive in tough economic conditions and they use children as dealers. At the same time, a long established system related to business protection is involved and this system also developed drug dealing activities. They have established their own passages, they have control over the flow of people in the square. It is not solely control over dealing but also a control over peoples and their flows”, Committee of Exarcheia Residents’ Initiative |

Concerning the police presence, local movements are accusing them for either doing nothing to stop drug dealing or supporting it.

| “The police and the state in general support it (drug dealing). We all know that the Greek state knows exactly what is going on and wants drug dealing to take place here in order to control it.” Local business owner |

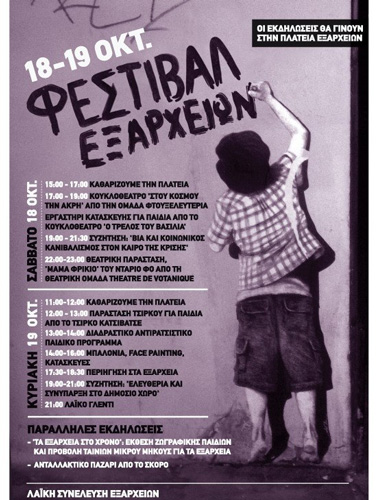

Attempts to tackle exclusionary conditions n Exarcheia Square, in the form of strategies and tactics, are developed on the behalf of local movements and businesses. Both independently and through a common structure (Exarcheia Peoples’ Meeting) that was created in spring 2014, the aforementioned actors have developed strategies and tactics that simultaneously attempt to directly confront drug dealing and its agents’ tactics and also create conditions of inclusion for the excluded groups of residents. Additionally, having anticipated local aggressive groups’ attempts to usurp the symbolic cohesion of the district, they re-define meanings and notions, such as freedom. To this end, they have created and extensively use the term ‘social cannibalism’ in order to describe the practices of antagonistic groups, whose sole purpose is the establishment of their power to the detriment of all others and the consequent results of exclusion.

| “These groups are trying to usurp political groups or notions and on many occasions they claim actions in their name. There is, for example, a drug dealer who sees you with a shaved head and he says, ‘I am an anarchist, you are skinhead, I consider you a fascist and I will beat you up.’” Committee of Exarcheia Residents’ Initiative |

The aforementioned actors’ strategies include the creation of territories within which those actors are the major influencers in terms of management and control and the reinvention of dominant notions and meanings. In terms of tactics, territories in which drug dealing and tactics of exclusion are not tolerated are created, while there are also attempts to re-establish lost associations of the excluded groups of residents through the introduction of new uses and the creation of physical infrastructure, designed for use from those groups.

Table 2: Contrasting territorial productions in Exarcheia Square

The aforementioned contrasting territorial productions co-exist in space but not in time. Territorial productions of exclusion have been established through their embodiment in the everyday life and the rhythms of the square. On the contrary, territorial productions of inclusion constitute ‘external’ creations. The case of Exarcheia Square makes it clear that control over a public space that is based mainly on the symbolic level and occasional use, without foundations built on uses and practices at the level of everyday life, is unstable and vulnerable. This parameter however, seems to be anticipated on the behalf of actors that pursuit an inclusive public space. Towards this end, their tactics and strategies attempt to intervene in everyday life through the establishment of practices and structures of self-reproductive nature, such as the creation of stable infrastructure addresses to the excluded parts of the district’s residents and the creation of a political venue that hosts the Exarcheia Peoples’ Meeting in the square, a development accompanied by interventions and actions on the level of everyday life.

| “There is a form of resistance but it has to take place in a more organized manner, with continuous massive actions in the square […] It is important to establish differentiated uses, to make people appropriate the square, so that they will not wait for the Residents’ Committee or Squat A to bring new uses. Those who are there must take actions, even if we are three people playing music. Is it possible to do our rehearsals in the square? Public space must be open to appropriation by everyone. Can we develop our everyday activity there?”, Committee of Exarcheia Residents’ Initiative |

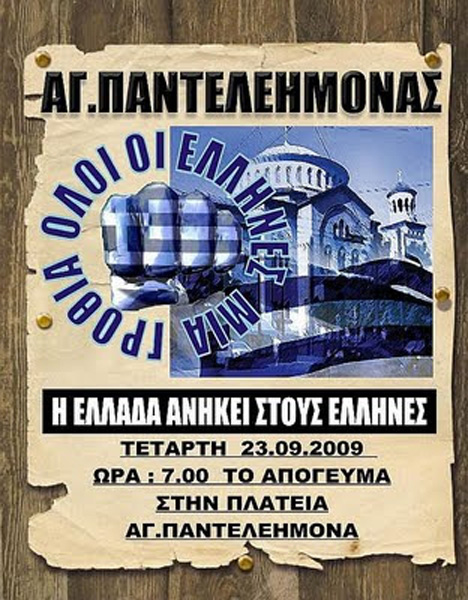

Agios Panteleimonas Square

Agios Panteleimonas Square is situated within the Agios Panteleimonas district that primarily hosts residential land uses. Agios Panteleimonas district was inhabited during the last decades from immigrants (Antonopoulos and Winterdyk, 2006; Arapoglou et al., 2009; Kandylis and Kavoulakos, 2012; Tsiganou, 2010), who also constitute both the most populous group of the square users and also represent, almost exclusively, the young population among those users. Before the current conflicts, immigrants used the square for play, recreation and social interaction.

Confronting this association, the local Residents’ Committee and the neo-Nazi organization of Golden Dawn developed tactics against immigrants’ associations. According to Kavoulakos (2013), such phenomena, that he considers to be part of a ‘rejection movement’, are traced in Agios Panteleimonas district since 2008 and it is in this district that this movement had a strong and successful – for its goals – presence. Those tactics constitute intentional attempts to establish control over the square under the claim of its ‘re-occupation by Greek users’. However, during field research, no actual conditions, tactics or practices of exclusion were spotted, apart from those developed on behalf of the above-mentioned actors. Residents’ Committee and Golden Dawn’s tactics do not confront exclusionary tactics and related practices but, instead, they embody racist narrations and target the ‘otherness’ in terms of national and racial identities. Practices developed within those tactics include the square’s occupation by participants and supporters of the exclusionary actors, accompanied by the ouster of immigrants, direct violent attacks against immigrants and the organization of political events by the Golden Dawn organization [4].

The content of ongoing conflicts concerns issues of identity and rights to the use of public space. Moreover, within these conflicts, control over public space is a secondary claim and a tool for racist groups to confront the population shifts in the district, since it is in public space that these shifts become apparent. Within this frame, the closing down of the square’s playground from the exclusionary urban actors can be explained as an attack against the playground’s role as a constant reminder that the young population in the district consists mainly of immigrants. The aforementioned tactics, supported by large parts of the district’s residents and business owners, along with the state’s broader strategies concerning migration and its tolerance towards exclusionary tactics, create a territory of insecurity for immigrant users.

In an attempt to tackle developments that could lead to the creation of an exclusionary space, tactics of inclusion were promoted by residents’ initiatives, political groups and anti-racist organizations. However, insecurity affected the right of presence and the tactics of the anti-exclusionary agents. These tactics consist mainly of short-term and fragile territorial productions through the organization of cultural activities that attempt to enforce immigrants’ association to public space.

Table 3: Contrasting territorial productions in Agios Panteleimonas Square

| “We could not get results. Even if someone could open the playground, as long as the rejection movement was uncontrolled, nothing could be accomplished. They closed down the playground on symbolic grounds, as the square was already under occupation. We could not even cross the square. Many of us that are known to them (the rejection movement), could not even walk on nearby streets. This condition does not exist anymore, as they are not that aggressive now. Since the occupation of the square took place, we could not organize anything. We just managed to organize one event in October, not by ourselves, but along with Open City and other anti-racist initiatives, and the people responded in a positive manner, despite the fact that they were afraid”, Initiative of the 6th District Residents |

The tension between contrasting territorial productions is amplified by to the lack of cohesion in attitudes concerning the content of conflict among users of the square and other actors, such as local businesses. This leads to a multileveled spread of the conflict. Conflicts in Agios Panteleimonas Square are accompanied by the district’s degradation in economic terms, as indicated by the fact that most properties, designed for businesses, around the square are not used, while property values and rents have significantly fallen, comparatively to surrounding districts.

| “It is in AgiosPanteleimonas that it was more intense (e.g. the fall of real estate values). I would say that the attention from the media played an important role, as the reproduction of the events that take place here influence people’s opinions. Especially on television there were numerous references to this specific district. Additionally, the residents’ presence in the media backfired, as other people consider the district to be degraded and this fact has damaged property values. Those people played a role in the degradation of their own properties”, Real estate agent |

Syntagma Square

Syntagma Square is among the most central and symbolic public spaces in Athens and directly falls into Iveson’s (1998) description of ceremonial public spaces. In such spaces, the state holds a dominant position in terms of control and functions; their attributes include a relation to symbolic / imaginary constructions and notions as well as historical events, large size and central position. Moreover, they host major and central events organized by a variety of actors such as the State, actors of the economy and social movements. Syntagma Square also relates to Lefebvre’s (1974) description of abstract space:

“We already know several things about abstract space. As a product of violence and war, it is political; instituted by the state, it is institutional. On first inspection it appears homogeneous; And indeed it serves those forces which make a tabula rasa of whatever stands in their way, of whatever threatens them – in short, of differences”

The surrounding area hosts economic and administrative functions and uses, as indicated by the operation of numerous businesses of multiple scales, services, luxurious hotels and several administrative buildings (the Parliament, embassies, ministries, public services). Moreover, Syntagma Square constitutes a major touristic landmark of Athens. Due to the lack of everyday life appropriations by groups of users, with the exception of skating activity, the square’s central position, the surrounding uses and the operation of the METRO station, constitute the major influencers of everyday territorial productions, as they create the conditions for users’ associations.

Users’ presence develops as part of everyday economic activities, such as commuting to and from workplaces and spaces of consumption. Thus, the square operates according to the economic territory that is the surrounding area. Associations develop due to the square’s position through individual practices such as crossing, short breaks and as a meeting point. In contrast to the previous cases, no conditions of exclusion are developed in Syntagma Square.

As indicated in the description of ceremonial public spaces, several appropriations are developed by numerous and different actors: institutional and official actors (the State, local authorities, political parties), market agents and social movements. Examples of relevant territorial productions include parades, social and cultural events organized by local authorities, events organized by political parties, commercial events and actions of protest. In all cases, the aforementioned territorial productions either reinforce or fail to challenge the square’s function as a territory controlled by the State and the market.

The stability and empowerment of this territory is based on institutional actors’ strategies and tactics. Strategies include planning and development frameworks and initiatives that reinforce the square’s functions. Tactics include the high density of police presence despite the low levels of relevant incidents, the instantaneous obliteration of traces of events that challenge the control of the State and market – even in short-term– and, finally, direct interventions by market actors in public space’s physical environment and infrastructures, as indicated by the assignment of restoration activities to a hotel owner [5]. Concluding, Syntagma Square constitutes a stable, enduring territory within which the State, local authorities and market forces are the dominant actors. The only contrasting territorial productions are the appropriations by social movements, while contrasting claims of control in the form of tactics are absent.

Conclusions

Following the cases of the three squares examined above, one can argue that in confrontational public spaces, the various forms of territorial production tend to be short-term and fragile. This tendency is a result of the contrasting character of territorial productions, which have to coexist often in conflict. Two exceptions were spotted in all three case studies: 1) the State and market have a stable territorial control in Syntagma Square and 2) the long-lasting ‘radical territory’ in Exracheia Square, which is, however, established exclusively on the symbolic level and only partially translated in relevant territorial productions on the level of everyday life. In both cases, the establishment of territories is indicated and accompanied by the lack of contrasting claims of control. In Syntagma Square, there is a lack of contrasting strategies and in Exarcheia Square, dominant notions are not challenged, but interpreted and embodied in differentiated ways within claims of control.

Several parameters of territorial production seem to come along with the condition of conflict. First, the form of territorial production that seems to be the most crucial is the one of tactics, as it constitutes a personalized and intentional claim of control, developed within the physical space of the squares and directly opposing other forms of territorial production. The importance of tactics is underlined by the fact that among all case studies, the one in which the condition of conflict is weakened and has limited influence on everyday life, namely the case of Syntagma Square, is characterized by the absence of contrasting tactics. Moreover, similar practices create different forms of territorial production, depending on whether they occur as claims of control or not. For example, events and protests by social movements and events by political parties lead to different forms of territorial production, as they constitute tactics in Exarcheia and Agios Panteleimonas squares and appropriations in Syntagma Square respectively.

Another crucial parameter is the embodiment of territorial productions in everyday life and in the rhythms of public space. Territorial productions that are developed and established within those rhythms appear to be far more stable and resilient, despite the fact that sometimes –as is the case of Exarcheia Square– they are opposed by all active urban actors. Finally, the ways and level of engagement in ongoing conflicts by public space’s users is a determining factor. The associations with public space produced by the majority of users, such as the use of cannabis in Exarcheia or recreation and play by immigrants in Agios Panteleimonas, are more resistant to opposing strategies and tactics and eventually more resilient.

[1] http://phdtheses.ekt.gr/eadd/handle/10442/36254″ target=”_blank”>http://phdtheses.ekt.gr/eadd/handle/10442/36254″>http://phdtheses.ekt.gr/eadd/handle/10442/36254

[2] In Exarcheia Square additional territorial productions, such as appropriations for commercial and recreational use, were traced. However, in this paper, I elaborate on territorial productions that are directly related to conditions of conflict and exclusion.

[3] For example, the destruction of infrastructure created by the Municipality of Athens and social movements, statues, means of public transport (http://www.efsyn.gr/arthro/vandalismos-stin-protomi-tis-lelas-karagianni-sta-exarheia and http://www.efsyn.gr/arthro/fotia-se-tria-trolei-konta-sto-polytehneio , In Greek)

[4] Concerning Syntagma Square, events organized by political parties are considered to be a part of appropriations instead of tactics. However, in the case of Agios Panteimonas Square, such events are accompanied by claims of control and constitute practices developed in the frame of exclusionary tactics

[5] http://www.aftodioikisi.gr/ota/dimoi/oasi-egine-i-plateia-sintagmatos-pos-apektise-tin-palia-tis-omorfia-aigli-foto/ (In Greek)

Entry citation

Pettas, D. (2017) The production of space under conflict conditions, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/space-under-the-condition-of-conflict/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.68

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Αράπογλου Β, Καβουλάκος Κ-Ι, Κανδύλης Γ, κ.ά. (2009) Η νέα κοινωνική γεωγραφία στην Αθήνα: μετανάστευση, ποικιλότητα και σύγκρουση. Σύγχρονα Θέματα 107: 57–66.

- Καβουλάκος Κ-Ι (2013) Κινήματα και δημόσιοι χώροι στην Αθήνα: χώροι ελευθερίας, χώροι δημοκρατίας, χώροι κυριαρχίας. Στο: Κανδύλης Γ, Μαλούτας Θ, Πέτρου Μ, κ.ά. (επιμ.), Το κέντρο της Αθήνας ως πολιτικό διακύβευμα, Αθήνα: ΕΚΚΕ, σσ 237–256.

- Πέττας Δ (2015) Ο δημόσιος χώρος ως πεδίο αστικών συγκρούσεων. Η επίδραση των σχέσεων εξουσίας στη καθημερινότητα και τις πρακτικές χρήσης. ΕΜΠ.

- Τσίγκανου Ι, Λαμπράκη Ι, Φατούρου Ι, κ.ά. (2010) Μετανάστευση και εγκληματικότητα: Μύθοι και πραγματικότητα. Τσίγκανου Ι (επιμ.), Αθήνα: Εθνικό Κέντρο Κοινωνικών Ερευνών.

- Antonopoulos GA and Winterdyk J (2006) The Smuggling of Migrants in Greece An Examination of its Social Organization. European Journal of Criminology, Sage Publications 3(4): 439–461.

- Deleuze G and Guattari F (1972) Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. 1st ed. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Deleuze G and Guattari F (1980) A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. 1st ed. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Iveson K (1998) Putting the public back into public space. Urban Policy and Research, Taylor & Francis 16(1): 21–33.

- Kandylis G and Kavoulakos KI (2011) Framing urban inequalities: racist mobilization against immigrants in Athens. The Greek Review of Social Research 136(3): 157–176.

- Kärrholm M (2005) Territorial Complexity in Public Spaces-A Study of Territorial Production at Three Squares in Lund. Nordic Journal of Architectural Research, Nordisk förening för arkitekturforskning 18(1): 99–114.

- Kärrholm M (2007) The materiality of territorial production a conceptual discussion of territoriality, materiality, and the everyday life of public space. Space and culture, Sage Publications 10(4): 437–453.

- Lefebvre H (1991) The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Pettas D (2015) Public space as a field of urban struggle: Everyday life practices as the outcome of power relations. The Greek Review of Social Research 144: 135–140.