The spatial planning framework for Athens City Centre. Aspects of strategic and normative planning

Triantis Loukas

History, Planning, Politics

2017 | Jun

This article contributes to the discussion on Athens City Centre, by examining the institutional framework of spatial planning for the City Centre and its significance, aiming to highlight aspects that remain less visible. Although the notion of institutional framework may refer to a wide spectrum of laws, rules and regulations, this article focuses on spatial planning tools, following the distinction between strategic and normative tools. Methodologically, the article is grounded on a systematic indexing of laws and presidential decrees, as well as material deriving from research projects, undergraduate and postgraduate classes at the School of Architecture of the National Technical University of Athens [1].

The term “Athens City Centre” takes into account the designation of the “Historic Centre” (ΦΕΚ 567Δ/1979) and the “Metropolitan Centre” (according to the General Urban Plan), as well as the administrative boundaries of Athens Municipality, though it serves as a more abstract reference, which maintains at its centre the “Historic Triangle” of Stamatis Kleanthis and Eduard Schaubert and contains the first municipal district and parts of the second and the third. The article underlines a complex relation between the institutional framework and the spatial evolution of the City Centre. On the one hand, even though the evolution of the City Centre cannot be understood as the spatial footprint of its regulation – and despite the prevailing perceptions on planning’s non-implementation – the article highlights the significance and the distinct role of the planning framework. On the other hand, the article underlines the selective use of this framework, which relates to social dynamics and practices of spatial development.

City Centre, visions and centralities for strategic planning

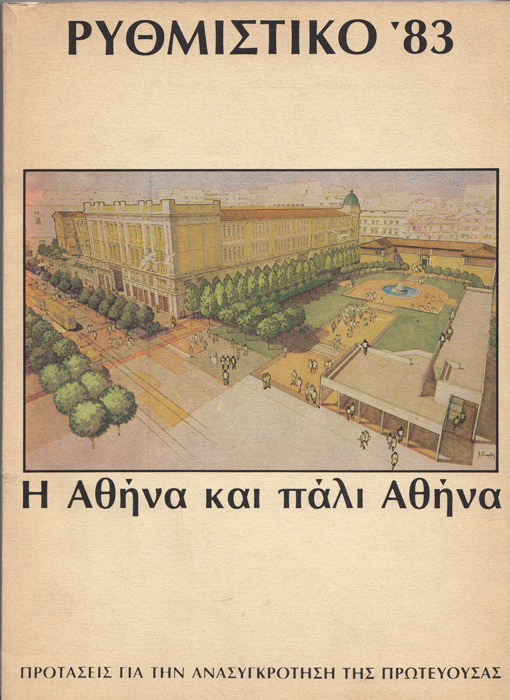

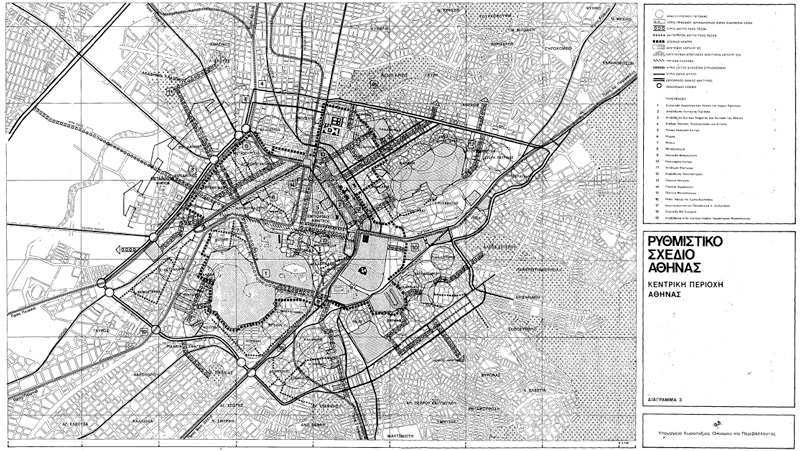

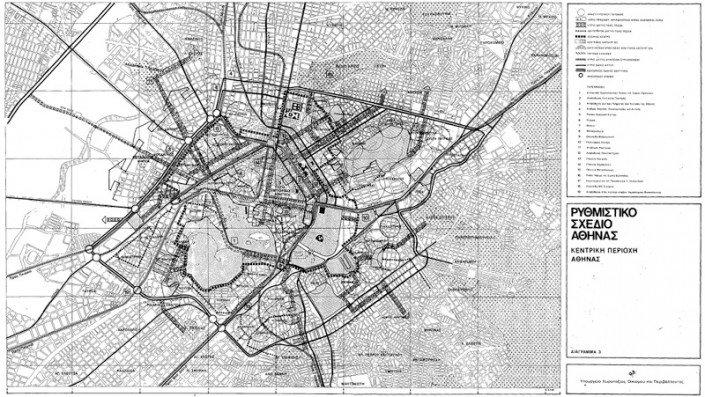

The Regulatory Plan of Athens (RPA) of 1983 (law 1515/1985, Government Gazette Issue 18Α/1985) marked in the beginning of the 1980s a breakthrough (also) for Athens City Centre, in the context of the formulation of a consolidated system of spatial planning in Greece (law 1337/1983, Operation of Urban Regeneration) [2] , while it was supported by the establishment of the Organisation for the Regulatory Plan of Athens (ORPA) (Γεράρδη, 1997, 1998) [3]. The goals of the RPA 1983 – under the eloquent title “Athens once again Athens” – (Figure 1) included: the “redistribution of activities”, the “poly-centric spatial organisation”, the decentralisation of public administration, the restriction of central activities and the decongestion of central districts. The RPA 1983 was promoting the enhancement of the historic character of the City Centre, the discouragement of wholesale and manufacturing activities and the encouragement of residential activities, the prevention of the through-passage of cars, a unified pedestrian network and the development of a tram network (though explicitly not a metro system) (Figure 2).

Figure 1: The cover of the Regulatory Plan of Athens 1983 under the title: “Athens once again Athens”. This depicts for the first time the pedestrianisation of Panepistimiou Street and the development of a tram line

Figure 2: Strategic provisions of RPA 1983 for the “Central Area of Athens”

These goals should be understood in the context of the significations that were attributed at that time to the growing levels of air pollution, as well as the so-called “hydrocephaly” of the capital city. At the same time, the RPA 1983 sought to respond to the intensive post-war development of the City Centre, the high building coefficients (which had further increased during the military dictatorship in the 1970s) and to what was perceived as a “distortion” of the historic character of the City Centre. Given that the the urbanisation rates had already slowed down and the City Centre had already been developed to a considerable extent, what appeared as a necessity was a shift towards the quality of life and urban regeneration, with a reference to the emerging significance of the protection of the environment and cultural heritage.

Since then, various arguments have been developed on the effectiveness of the RPA 1983, ranging from the argument that its contributions was “from zero to minimal” (Αραβαντινός, 2002), to the argument that it “marked the planning conceptions, as well as a great part of the policies and the technical practices on urban issues” (Γεράρδη, 1998: 44). As contradictory as these opposing views may seem, in the present article we claim that they contain aspects of the same reality.

To begin with, it becomes evident today that many directions of the RPA 1983 were somehow implemented during the following decades, among others: the “creation of a polycentric spatial organisation” with the development of new urban centres outside the City Centre; the “redistribution of public administration” with the partial removal of ministries from the City Centre (though not towards the west); the “concentration of wholesale activities outside the Athens Basin (though not always in suitably designated zones); and the “transfer of the dispersed industrial units from residential areas” (Γεράρδη, ό.π.: 46-7).

We could, thus, argue (not without some merit) that the emphatic promotion of the return of residential activities and the historic character of the City Centre, regardless of the initial intentions, gradually contributed to the weakening of the “multi-functionality”, the erosion of social inclusiveness and to vacant buildings, since land uses that were “decongested” were not replaced by others (ΕΜΠ – ΥΠΕΚΑ, 2012).

At the same time, we could argue (also not without some merit) that although these changes were provided by the planning framework, they did not take place exactly because of it, but can be related to wider processes of spatial development. For instance, the functional “decongestion” of the City Centre, although it formed an explicit policy of the RPA 1983, it may be further linked to the dynamics of the domestic construction sector, the change in scale and structure of the land-and-construction system, as well as new cultural and consumption patterns. It could also be understood, to some extent, in the context of much wider trends of urban sprawl, and outer-urbanisation, which were recorded at the same period on a global scale (Soja, 2000).

These remarks urge us to reflect on what would be the evolution of the City Centre if the RPA 1983 had not existed and, in turn, on how useful this has been and for whom.

A first argument to be made is that the selective implementation of RPA 1983 satisfied various market demands in a second time, in different contexts and of different goals. For instance, a partial transfer of public administration was implemented after 2000, thus intensified the declining trends of central areas, by removing employees from the City Centre and subsequently destabilising accompanying activities and economies of scale (Χατζημιχάλης, 2011) [4]. On a parallel level, the RPA 1983 served as a guide for the gradual implementation of large-scale interventions, par excellence the pedestrian walk under the Acropolis, as managed by the Company for the Unification of Archaeological Sites of Athens (UASA), while also as a constant reference for iconic rehabilitation projects that ever since have re-emerged as urban visions in public debates, including the interventions in Panepistimiou Street, the Academy of Plato, the Interwar Refugee Complex in Alexandras Avenue and the area of Elaionas.

A second argument to be made is that it was, arguably, fairly convenient for the RPA 1983 to remain in effect, though as “obsolete”, so as this could more easily get bypassed by modifications of an “emergency status”. This argument can be supported by the fact that the Olympic Games of 2004 were based on the same Regulatory Plan (of 1983) with modifications, through ad hoc procedures, thus introducing a different approach for the regulation of space (Ευαγγελίδου, 2004, Ηλιοπούλου, 2004, Σταθάκης και Χατζημιχάλης, 2004), which failed to take into account the concurrent spatial and social dynamics of Athens (Βαΐου κ.α., 2004, Μαντουβάλου 1996α, 2010). As should further be mentioned, the design of the new metro system, whose development has had a decisive impact on the evolution of the City Centre, was elaborated by the Company Attiko Metro, on a parallel level to the RPA 1983 and its provisions.

In any case, the RPA 1983 remained typically in effect for as long as thirty years, until 2014, when the new Regulatory Plan “Athens-Attica 2021” was issued [5] . This conjuncture was different from many respects. On the one hand, due to the “crisis of the City Centre”, including the reduction of the registered population of Athens Municipality, the widening of vulnerable groups and urban poverty, phenomena of xenophobia and racism, the declining and partly vacant building stock (see ΕΜΠ-ΥΠΕΚΑ, 2012, Μαντουβάλου et al., 2011), as well as the dominant discourses on this crisis (encounterathens, 2011, Καλαντζοπούλου et al., 2011). On the other hand, due to the new institutional environment, in the context of the Memorandum regime, including the abolition of ORPA and UASA, the introduction of new laws and planning tools and the more direct involvement of the private sector in planning issues (Βαΐου, 2014).

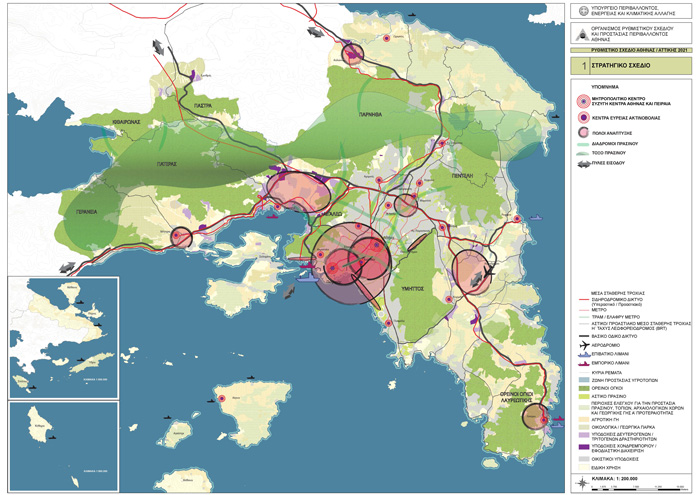

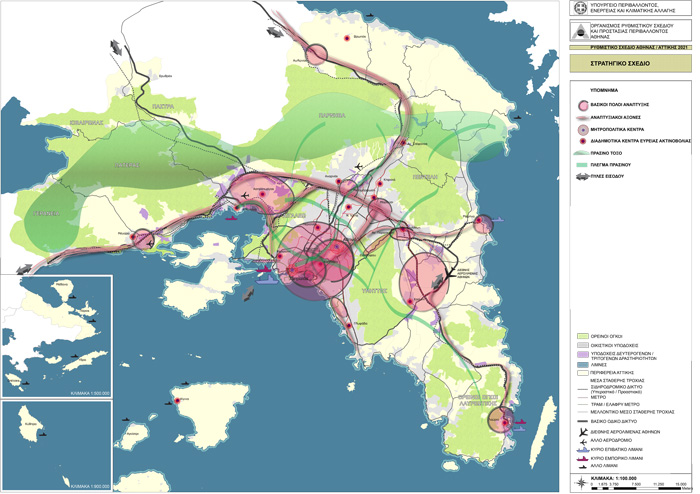

The processes of conducting the new Regulatory Plan led, in a first time, to a draft law in 2011 (RPA/2011) and, in a second time, to the final version that was voted in 2014 (RPA/2014) (law 4277/2014, ΦΕΚ 156Α/2014). The comparative analysis of the first and the second versions of the new Regulatory Plan presents a particular interest, to the extent that it highlights the tensions between different conceptions and goals for the City Centre (Figure 3, 4).

Figures 3 & 4: The map of the “Strategic Plan”, from the version of the RPA/2011 and the final version RPA/2014 (in effect). Along with the “Metropolitan Centre” and the “Development Poles”, the second version introduces the “Development Axes”

In particular, the draft law of RPA/2011 was attempting to pick up the thread from the RPA 1983, by addressing particular emphasis on issues of centrality. Instead of “decongestion”, the new RPA was speaking of the model of “compact city” and explicitly set as a goal the renewal of the existing building stock. One of its directions was the “integrated regeneration” of the City Centre and some of its axes included the restrain in the removal of public administration, the enhancement of activities and jobs, the promotion of residential activities, the invigoration of the vacant building stock, the promotion of public transport and so on. On the contrary, the second and final version of 2014 was omitting phrases as “stimulating centrality”, “halting urban sprawl”, “functional densification”, the “inclusive character of the City Centre”, the “revitalisation of production”, or “the prevention of private transportation”. In addition, the final version was adding a set of parameters that were contradicting towards the centrality of the City Centre, including the “Development Axes” (along the main road network), more flexible provisions for the development of malls outside the City Centre and the development pole in the former airport of Hellinikon.

The differences between the two version of the new Regulatory Plan reflect the divergence of conceptions of those who are involved in the processes of drafting the strategic plans: politicians, professionals, academics and members of public administration. They highlight the ambivalences on the intentions of planning, as for instance on how pro-development or pro-environment it should be. Subsequently, these different conceptions reflect the intensity of the challenges on the development of urban space and the pressures from economic and technocratic networks to meet development demands through planning (Μαντουβάλου, 2014); which demonstrates that strategic planning does matter.

City Centre and land use zoning for normative planning

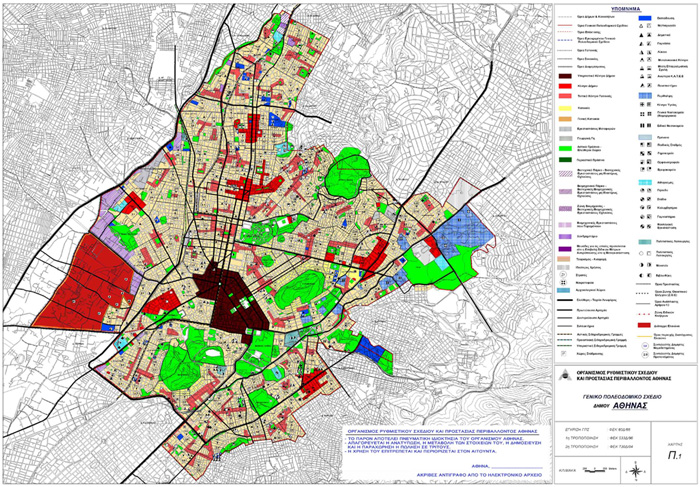

On the level of normative planning, the General Urban Plan (GUP) of Athens Municipality of 1988 (Ministerial Decision 255/45/1988, Government Gazette Issue 80D/1988, with amendments) was specifying a series of general directions from the RPA 1983 (Figure 5). The GUP was designating as “Metropolitan Centre” the “Commercial Triangle”, the area around Omonoia Square and the street axes of Akadimias, Panepistimiou and Stadiou. The provided land use zones within this “Metropolitan Centre” were those of the “urban centre”, “local centre” and “general residential activities”, which contained a wide spectrum of activities (according to the Presidential Decree 166/1987) and, in fact, reflected the multifunctional, mix-use character of the City Centre.

Figure 5: The General Urban Plan of Athens Municipality

As a specification of the RPA 1983, the GUP 1988 was also promoting the “decongestion” of central areas, as well as the stimulation of local centres within the boundaries of Athens Municipality, while also provided for the control and gradual restraint of new “central” activities along the main road axes. It was, again, aiming at the enhancement of the historic character of the City Centre, the control of land uses and the reduction of building coefficients, as well as the stimulation of residential activities, along with restrictions on the allocation of new offices and retail activities.

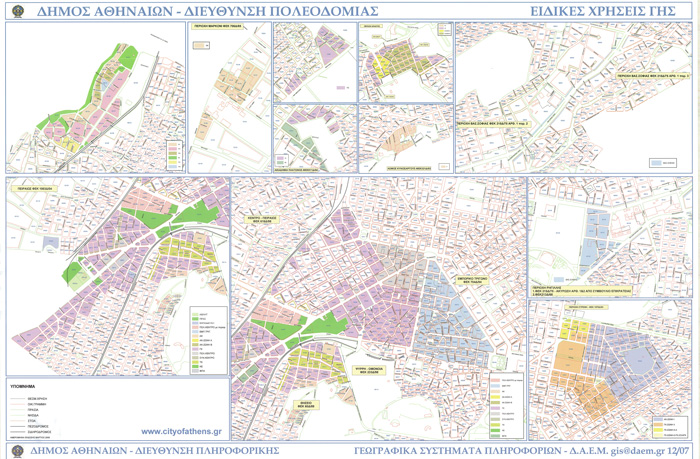

As further specifications of the GUP 1988, a series of Presidential Decrees were conducted and set into effect from the 1980s until the 2000s, regarding land use zoning for neighbourhoods of the City Centre (Figure 6) (βλ. και ΕΜΠ-ΥΠΕΚΑ, 2012) [6] . In particular, Presidential Decrees of the 1980s specified land use zones for the areas of Plaka (ΦΕΚ 617Δ/1980,ΦΕΚ 1329Δ/1993) and Thisseion (ΦΕΚ 60/1989); namely the areas of the old city, close to the Acropolis. The elaboration of the Presidential Decrees intensified in the 1990s, for the areas of Exarcheia (ΦΕΚ 1075Δ/1993), Mets (ΦΕΚ 1150Δ/1993), the “Commercial Triangle” (ΦΕΚ 704Δ/1994), Psyrri / Omonoia (ΦΕΚ 233Δ/1998) and Metaxourgeio (ΦΕΚ 616Δ/1998, with amendments) and was further supported by urban regeneration projects [7] and pedestrianisation projects (Κανελλοπούλου, 2016). The last decree to be issued was that for the (former) industrial axis of Piraeus Street, which contained the area of Gazochori, in the mid 2000s (ΦΕΚ 1063Δ/2004, with amendments).

Figure 6: Specific land uses of Athens Municipality, according to the relevant Presidential Decrees

These decrees were specifying the activities allowed or prohibited, those protected and those that were discouraged. It is worth noting that – despite the prevailing perceptions – many of the provisions contained in these Presidential Decrees were indeed implemented and that these had a considerable impact on the evolution of central neighbourhoods. Some of the provisions implemented according to the decrees was the protection of residential activities, culture and public administration along Vassilissis Sofias Avenue, the protection and promotion of residential activities and the restriction of recreation activities in Mets and Plaka (Ζήβας, 2006),

and even the development of a certain type of recreation activities in Metaxourgeio. Furthermore, the decrees for the “Commercial Triangle” and Psyrri seem to have contributed to the weakening or even the removal of wholesale and manufacturing activities and subsequently a wide range of accompanying activities, including residential. These remarks, once again, do not entail linear connections of direct causality between the planning framework and the evolution of the City Centre.

Subsequently, a series of observations on the relations between the land use normative framework and the dynamics of manufacturing, residential and recreation activities will enhance our understanding:

Manufacturing:

The GUP 1988 and several Presidential Decrees (for the “Commercial Triangle”, Psyrri / Omonoia, Metaxourgeio) have attempted to restraint manufacturing, processing and wholesale business activities from central areas. Moreover, the decree for Piraeus Street was restricting productive activities, by designating a large part of the axis as an “industrial park under regeneration”; thus promoting activities of the tertiary sector. Today, these policies may seem contested up to a certain extent. Although they have aimed at a more rational and environment-friendly delineation of the land uses, they have, nonetheless, contributed in the long run to the functional weakening of these areas, to vacant building stock and to the indirect displacement of population, workers or residents. Once again, it would be inappropriate to attribute the weakening of manufacturing activities only to the implementation of the Presidential Decrees, as we should take also into account a series of laws and state policies (ΕΜΠ κ.α., 1996), the de-industrialisation trends and the wider restructuring of the productive sector in the 1980s, the subsequent EEC, EU and Eurozone accession, as well as economic interests on the local level related to the real estate market and land speculation.

Residential activities:

Residential activities were promoted as a direction in most of the Presidential Decrees for City Centre neighbourhoods. In cases such as Plaka and Mets, it seems that this policy has been largely effective, although it may have contributed to some kind of gentrification. In other cases, such as the “Commercial Triangle” and Psyrri / Omonoia, residential activities were only sporadically enhanced, as the anticipated demand in the real estate market did not develop. Another factor that also contributed to this was that the recreation activities were largely remained uncontrolled, while also the fact that the decrees were in fact excluding the provisions for residential activities for those buildings of a non-residential initial land use (such as the prevailing typology of the manufacturing / business building) and, in general, because they were promoting residential activities in a normative way, though without providing a driving framework for their development. Over the last years, the dynamics of residential activities tend to transform, due to the development of short-term lodging schemes and the decline in real estate values. Nonetheless, as should also be noted, the provisions for the enhancement of residential activities somehow and up to a certain extent, especially around Omomoia Square, through the informal habitation of migrant and other vulnerable groups.

Recreation activities:

As has become evident, recreation activities seem to elude from the normative planning framework and often develop in similar ways, both in areas for which decrees have been issued (such as Gazi, Psyrri, Thisseio, Exarcheia, the “Commercial Triangle”) and in areas not regulated by them (such as Petralona or Koukaki). As an exception we could consider the area of Metaxourgeio, where the Presidential Decree seems to have somewhat directed the development of a “neo-traditional” type of recreation activities. The deviation between the normative provisions and reality with regard to recreation activities entails two aspects. On the one hand, there are deviations from the normative provisions, such as the development of large-scale recreation centres along Iera Odos (where exclusive residential activities are provided), Piraeus street (despite the restriction regarding the general residential activities) and in the area of Gazi, where the normative land uses have been bypassed through ministerial decisions. On the other hand, this deviation stems from the inadequacy of the decrees to regulate the “aggressive” expansion of recreation activities, the commercialisation of central areas, but also the fact that recreation has been regulated by other types of normative provisions beyond the presidential decrees.

In any case, the intense development of recreation activities in the City Centre since the late 1990s is a phenomenon linked both to the operation of the metro system and to a series of economic parameters and new consumption patterns of the Greek society but also to global trends related to urban tourism and the transformation of central areas into “thematic parks” (Μίχα, 2007),while in the midst of the crisis, the development of recreation activities has emerges as an economic alternative / way-out.

Challenges and questions on the spatial planning framework of the City Centre

The current conjuncture is very different from the 1980s, when the bases for both the strategic and normative framework for spatial planning of the City Centre took shape. Apart from the fact that we live in a substantially different City Centre, the present condition is characterised by:

- a new institutional framework that attempts to redefine the goals and objectives of spatial planning in general (urban planning, land-use planning and spatial development), together with new “fast-track” planning tools, but also strategic / operational tools that refer to a variety of spatial scales, such as the Integrated Urban Intervention Plans (IUIP) and the Integrated Spatial Investments (ISI).

- a fragmentation of actors who have (or claim to acquire) a competent role in the evolution of the City Centre, including the Municipality of Athens, the Region of Attica, the central administration (in different versions), cultural institutions, public benefit foundations and the private sector, while public organisations that used to hold a key role in the development of the City Centre, such as the ORPA and the UASA have been abolished or absorbed.

A characteristic feature of the current conjuncture is the fact that new planning tools and legal arrangements often do not replace the older ones but coexist with them. This gives way to a gradual juxtaposition of successive layers of planning tools, from different periods, which reflect different planning conceptions and different priorities.

In particular, there exists a recently established strategic planning framework (and) for the City Centre (RPA 2021), while on a normative level laws and presidential decrees from the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s continue to be in effect, along with a series of legal provisions, which are based on them, or may also operate autonomously. At the same time, modifications are sometimes made into the “obsolete” normative framework, when deemed necessary, usually under the pressure of economic interests [8] . On a parallel level, the central administration or the Municipality of Athens have occasionally announced urban regeneration projects, new planning and funding tools have been used, such as the IUIP and ISI, which may only cover parts of the City Centre and its problems in a fragmentary fashion, while pilot platforms have been tested with a decisive involvement of the private sector. The contradictions that arise are highlighted in particular in cases where the Council of State is called to interpret the ambiguities of the legal framework; thus directly influencing the policies for the City Centre and its evolution, tending sometimes to substitute planning itself [9] .

Despite the multiplicity of goals and objectives, planning tools and actors, a public debate on the planning framework for the City Centre has not been triggered so far; neither from planning professionals or technical associations; central or local government; or the market forces. Overall, significant difficulties in implementing a coherent strategy for the City Centre remain, both on the level of competence and on the choice of the suitable spatial scale, planning tools, planning procedures and mechanisms appropriate to intervene on the City Centre in the current conjuncture. As a result, the planning framework for the City Centre remains a field that offers fruitful ground for a wide range of misinterpretations, divergences and deviations. On the one hand, policies and plans that have been bypassed by reality or have empirically proven to fail are still in effect. On the other hand, divergent planning procedures are recorded.

By utilising an approach that takes into account the scales of invested capital and ownership (Massey and Catalano, 1978; Mantouvalou, 1996b) we could argue that the small and medium scale capital of businessmen, owners and residents of the City Centre is still obliged to follow the restrictive normative provisions of the previous decades, or chooses to bypass them through informal procedures and practices. On the contrary, the larger scale capital, if and when interested for the City Centre, may implicitly or explicitly influence and modify the current planning framework. The fact that the planning framework is considered as “obsolete” may legitimise its modification, even if this is fragmented.

The analysis of the strategic and normative planning framework for the City Centre of Athens demonstrates the distinct role of the institutional framework in the evolution of the City Centre. It disputes arguments that present planning as irrelevant and non-applicable, while also others that blame the bureaucratic legal framework for all the City Centre’s problems. Instead, we claim that planning does exists and that it has operated on several occasions, though it has been used selectively. In turn, the planning tools, whether strategic or normative, are only a part of the City Centre’s policies, policies that are wider; sometimes they relate to these planning tools, while others they bypass them.

Furthermore, it would make sense to overcome the question of whether and how the planning framework for the City Centre has been implemented and to reflect on whether it would have been preferable for this planning framework to have had applied as such and, even more, whether we continue to insist on its implementation today. The above analysis suggests that the selective implementation of the planning framework has had both positive and negative impacts, as did its non-implementation. From this perspective, we would argue that the real issue does not lie in the implementation or effectiveness of the institutional framework but, on the contrary, on the meaning and significations of the laws, the planning regulations and arrangements and, more broadly, on what kind of City Centre we want planning to lead us to.

Contrary to previous decades, in today’s conjuncture it seems that the imaginary of “what City Centre we want” lacks coherence, and that the strategy for its future evolution remains contested. A series of issues on the land uses and the social groups to which they correspond, the multifunctionality and social inclusivity of the City Centre, the concentration or decentralisation of urban development, the development prospects and possible ways of intervening on the existing built environment, as well as for the prospects of a bottom-up widening of the planning processes, remain pending.

[1] I would like to thank Maria Mantouvalou, emeritus professor NTUA, for her contribution on the evolution of this text. Furthermore, I would like to thank Yannis Polyzos, emeritus professor NTUA, Maria Mavridou, former assistant professor NTUA, and Panayiotis Tournikiotis, professor NTUA, scientific supervisor of the research programme “Changing characters and policies for the City Centres of Athens and Piraeus” (ΕΜΠ-ΥΠΕΚΑ, 2010-2012), along with all the member of the research team.

[2] These attempts can be understood as a deviation from the dominant trends in spatial planning in the 1980s in the many countries of the “west”, in the context of the advance of neoliberalism.

[3] For previous regulatory plans of Athens see Σαρηγιάννης, 2010.

[4] According toΧατζημιχάλη (2011), until 20009 eight ministries and central public services had been removed from the City Centre, along with 4-5.000 employees.

[5] The discussions for a new Regulatory Plan began in the end of 2000s, while a draft law in 2009 was never put in effect.

[6] We could also add the Presidential Decrees for Vassilissis Sofias Avenue (ΦΕΚ 215Δ/1975, με τροποποιήσεις), and Iera Odos Street (ΦΕΚ 391Δ/1985).

[7] It is worth noting the rehabilitation project assigned by Athens Municipality to the Laboratory of Urban Planning Research NTUA: “Commercial Triangle of Athens City Centre”, 1989-1991, see Αραβαντινός, 1997.

[8]One of these cases refers to the modification of the General Urban Plan of Athens Municipality in the area Akadimia Platonos (Academy of Plato), in order to facilitate the development of a large-scale commercial and recreation centre. Another case refers to the modification of the Presidential Decree for Piraeus Street, in order to legitimise the development of a large scale night club on Iera Odos Street.

[9]We could not omit to mention here the decisive intervention of the Council of State in the rehabilitation of Panepistimiou Street (see Σκάγιαννης et al, 2013). The interpretation of the legal framework by the Council, was grounded on both the contradictions of the legal framework and the divergence between the two versions of RPA/2011 and RPA/2014, as examined above. The final version of RPA was undermining as a non-defined “intervention” what the first version was describing as “pedestiranisation” and “urban regeneration of the Centre based on the axis of Panepistimiou Street”.

Entry citation

Triantis, L. (2017) The spatial planning framework for Athens City Centre. Aspects of strategic and normative planning, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/spatial-planning/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.72

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Αραβαντινός Α. (1997), Πολεοδομικός Σχεδιασμός – Θέματα από τη Θεωρία και την Πρακτική, Αθήνα: ΕΜΠ.

- Αραβαντινός. Α. (2002), Δυναμικές και σχεδιασμός κέντρων στην πόλη των επόμενων δεκαετιών – προς συγκεντρωτικά ή αποκεντρωτικά σχήματα;, Αειχώρος, 1 (1): 6-29.

- Βαΐου, Ντ., Μαντουβάλου, Μ. και Μαυρίδου, Μ. (2004), Αθήνα 2004: Στα μονοπάτια της παγκοσμιοποίησης, Γεωγραφίες, 7: 13-25.

- Βαΐου, Ντ. (2014), «Ιδιωτικοποίηση του σχεδιασμού. Κατάργηση του ΟΡΣΑ & Reactivate Athens: Ιστορίες παράλληλες αλλά όχι ασύμπτωτες», Ενθέματα Αυγής, 22 Φεβρουαρίου 2014, διαθέσιμο στο: https://enthemata.wordpress.com/2014/02/22/dinva/#more-14388=, [πρόσβαση 10 Μαρτίου 2017].

- Γεράρδη, Κλ. (1997), «Ρυθμιστικά σχέδια μητροπολιτικών περιοχών – Η περίπτωση της ευρύτερης Αθήνας», στο Αραβαντινός κ.α., Πολεοδομικός Σχεδιασμός – Θέματα από τη Θεωρία και την Πρακτική, Αθήνα: ΕΜΠ.

- Γεράρδη, Κ. (1998), Η στρατηγική του σχεδιασμού για μια βιώσιμη ανάπτυξη της Μητροπολιτικής Περιοχής της Αθήνας. Πλαίσιο κατευθύνσεων και προτεραιοτήτων, Αθήνα: ΕΜΠ.

- ΕΜΠ, ΒΕΑ και ΒΕΠ (1996), Μικρομεσαίες Μεταποιητικές επιχειρήσεις στον ιστό της πόλης, Πρακτικά συνεδρίου, Μάϊος 1996.

- ΕΜΠ – ΥΠΕΚΑ (2012), Μεταλλασσόμενοι χαρακτήρες και πολιτικές στα Κέντρα Πόλης Αθήνας και Πειραιά, ερευνητικό πρόγραμμα, επιστημονικός υπεύθυνος Π. Τουρνικιώτης.

- encounterathens (2011), Σχεδιασμοί για το κέντρο της Αθήνας στη συγκυρία της κρίσης, διαθέσιμο στο: https://encounterathens.wordpress.com/2011/05/14/σχεδιασμοί-για-το-κέντρο-της-αθήνας-στ/ [πρόσβαση 10 Μαρτίου 2015].

- Ευαγγελίδου, Μ. (2004), Θεσμικές προϋποθέσεις για την άσκηση μιας πολιτικής τόνωσης του διεθνούς ρόλου της Αθήνας, Γεωγραφίες, 7: 127-135.

- Ζήβας, Δ. (2006), Πλάκα 1973-2003. Το χρονικό μιας επέμβασης για την προστασία της παλαιάς πόλεως Αθηνών, Αθήνα: Πολιτιστικό Ίδρυμα Ομίλου Πειραιώς.

- Ηλιοπούλου, Ε. (2004), Διαδικασίες Στρατηγικού Σχεδιασμού της Αθήνας και ένταξη σε αυτόν δράσεων σχετικών με τους Ολυμπιακούς Αγώνες, Γεωγραφίες, 7: 118-127.

- Καλαντζοπούλου, Μ., Κουτρολίκου, Π., και Πολυχρονιάδη, Κ. (2011), Ο κυρίαρχος λόγος για το Κέντρο της Αθήνα, διαθέσιμο στο: https://encounterathens.wordpress.com/2011/05/15/o-κυρίαρχος-λόγος-για-το-κέντρο-της-αθήν/ [πρόσβαση 10 Μαρτίου 2015].

- Κανελλοπούλου, Δ. (2016), Πεζοδρομήσεις στο κέντρο της Αθήνας : σύντομο ιστορικό και ερωτήματα, στο Μαλούτας, Θ., Σπυρέλλης, Σ. (επιμ.) Κοινωνικός Άτλαντας Αθήνας. Ηλεκτρονική συλλογή κειμένων και εποπτικού υλικού (http://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/άρθρο/πεζόδρομοι-στην-αθήνα/)

- Μαντουβάλου, Μ. (1996α), Κέντρο πόλης, κοινωνική ανισότητα και πολιτισμική ετερότητα. Προκλήσεις για την πολεοδομική σκέψη, Μανδραγόρας, 12-13: 54-55.

- Μαντουβάλου, Μ. (1996β), Αστική γαιοπρόσοδος, τιμές γης και διαδικασίες ανάπτυξης του αστικού χώρου ΙΙ. Προβληματική για την ανάλυση του χώρου στην Ελλάδα, Επιθεώρηση Κοινωνικών Ερευνών, 89-90: 53-80.

- Μαντουβάλου, Μ. (2010), Κρίση του Κέντρου Αθήνας;, Εισήγηση στην επιστημονική ημερίδα «Κέντρο και Κεντρικότητες, Παρίσι – Αθήνα: Συγκρίσεις», 10 Μαΐου 2010, Αθήνα.

- Μαντουβάλου, Μ. (2014), Σημειώσεις για το Ρυθμιστικό Σχέδιο ως πολιτικό διακύβευμα, Οικοτριβές, 26 Ιανουαρίου 2014, διαθέσιμο στο: https://oikotrives.wordpress.com/2014/01/26/rsa-mantouvalou/ [πρόσβαση 10 Ιανουαρίου 2016]

- Μαντουβάλου, Μ., Σκούφογλου, Μ., και Παλιού, Χ. (2011), «Το Ιστορικό Κέντρο της Αθήνας», στο Χατζημιχάλης, Κ. (επιμ.) Σύγχρονα Ελληνικά Τοπία, Αθήνα: Μέλισσα.

- Massey, D. και Catalano, A. (1978), Capital and Land: Landownership by capital in Great Britain, London: Edward Arnold.

- Μίχα, Ε. (2007), Θεματικές παρεμβάσεις στην πόλη: χαρακτηριστικά και συνέπειες, Επιθεώρηση Κοινωνικών Ερευνών, 123 Β: 3-29.

- Σαρηγιάννης, Γ. (2010), Τα ρυθμιστικά σχέδια Αθηνών και οι μεταβολές των πλαισίων τους, Greekarchitects, διαθέσιμο στο: http://www.greekarchitects.gr/gr/αρχιτεκτονικες-ματιες/τα-ρυθμιστικά-σχέδια-αθηνών-και-οι-μεταβολές-των-πλαισίων-τους-id3464 [πρόσβαση 10 Μαρτίου 2015].

- Σκάγιαννης, Π., Χατζημιχάλης, Κ., Ρωμανός, Α., Πολλάλης, Σ.Ν., Κονταργύρης, Δ., Βεντουράκης, Α., και Σουλιώτης, Ν. (2013), Rethink Πανεπιστημίου – Ο αντίλογος, Αειχώρος 18: 158-205.

- Soja, E., (2000), Postmetropolis, Critical Studies of Cities and Regions, Oxford: Blackwell.

- Σταθάκης, Γ., και Χατζημιχάλης, Κ. (2004), Αθήνα διεθνής πόλη: από την επιθυμία των ολίγων στην πραγματικότητα των πολλών, Γεωγραφίες, 7: 26-47.

- Χατζημιχάλης, Κ. (2011), «Το δημόσιο έλλειμμα σχεδιασμού για την πόλη», Εποχή, 19 Δεκεμβρίου 2011, διαθέσιμο στο: http://www.epohi.gr/portal/politiki/10856- = [πρόσβαση 10 Μαρτίου 2015].