2015 | Dec

Bustling and colourful markets in the city’s neighbourhoods are a familiar image in Athens and in the major municipalities of the Attica basin. Farmers and professional retailers compete against each other behind their stalls, advertising their high-quality but affordable products. “Here, here buy cheap from me”, “test your watermelon on the spot”, “Get hormone-free products for your babies” are some of their familiar calls to consumers. For years, street markets have been places where Athenians of all ages and incomes buy and sell products.

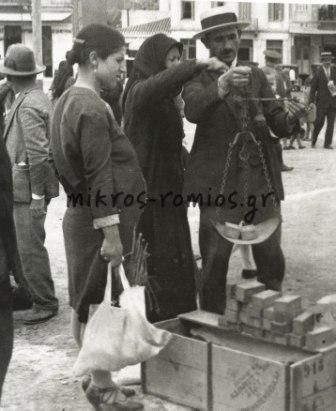

Street markets were established in 1929 by Eleftherios Venizelos as a policy to address speculation and fraud during the the economic crisis in the interwar period. They immediately were faced with strong protests by professional organisations and intermediaries, who threatened producers that they would stop cooperating with them. These reactions were due to the fear of wholesalers and intermediaries that they would suffer losses from this new institution involving the direct sale of agricultural products by producers to consumers (Σκιαδάς 2014). However, street markets were quickly embraced by Athenians and have since remained a stable institution that shaped household shopping patterns and commercial activities in the city’s neighbourhoods.

The first street market operated in Thission with gardeners from Agios Savvas Eleonas, Kolokynthou, Moschato, Rendi, Maroussi, Halandri, Menidi, Megara etc. Its success led to a need for better institutional organisation, thus the Street Market Fund was established in 1932 (Σκιαδάς 2014). Since then, street markets expanded their number of stalls and the variety of goods offered, and the neighbourhoods of Athens hosting them have multiplied. Today, 180 street markets operate in the area of the former Prefecture of Athens-Piraeus (today the Region of Attica). Out of these, 44 are located within the limits of the City of Athens . The markets’ smooth operation and services to merchants and producers fall under the jurisdiction of the Athens-Piraeus Street Market Organisation (APSMO – former Street Market Fund), a self-financed public organisation operating as a public body (www.olaa.gr).

Over the years, the sources of vegetables and fruit but also of other goods such as legumes, honey, olives, eggs, fish etc. expanded. Now, producers come from Euboea, Boeotia, Corinth, Argolida, Ilia and, of course, the peri-urban areas of Marathon, Menidi and Megara. Today, thanks to the modernisation of highways and transport, as well as to new technologies for storing and refrigerating perishable goods, fruit from all over Greece arrives to Athens’ street markets from big and small producers and cooperatives -for example Agia apples, Naoussa peaches, Vodena cherries (Edessa). Pulses, rice, olives, wines from Mesogeia directly from the producer -all bearing the Protected Designation of Origin designation- are also highly regarded by consumers, who prefer bulk products to the standardised ones that are otherwise available in supermarkets. “Standardised products contain preservatives to ensure they last in packaging. Here I know exactly what I buy and where it came from”, comment aware consumers.

The main reason to prefer street markets to supermarkets is the freshness and variety of products as well as prices.

| The supermarket is a one-way road. There, consumers find two types of tomato qualities and that’s it. Other than that, many products are already packed in nylon bags. Here in the street market, consumers will find 20 different stalls with tomatoes. Some are grown from Greek seeds, others are curlier, others shinier, from a greenhouse…. In some stalls, they will look at the sign with the place of origin. ‘It is from Nafplion’ they’ll think, ‘my place of birth’…. They instinctively buy, ask, taste and get informed. Next week, they’ll come again and try something new. With time they train, they get better. Do you ever ask that kind of information from an employee at the super market?

(Vangelis, producer from Megara). |

Street markets target all social groups and budgets. Early in the morning, when top-end products are placed in the stalls, the main customers are consumers interested in quality regardless of price. It is generally accepted that the quality-price ratio in street markets is superior to that of large supermarket chains. As time progresses, prices drop and lower income strata make their appearance.

| Now, with the crisis, most people in poor neighbourhoods gather at noon and we spend our mornings doing nothing (…). We try to help as much as we can; When we see that some people are struggling to make ends meet… we’ll put something extra in their bag

(Nikos, retailer). |

On the other hand, consumers build a relationship of mutual trust with their greengrocer in the street market, as they discuss and get information about the varieties of fruit and vegetables, their origin, how to store and cook them. Some sellers place rare local varieties on their stalls: firiki apples from Pelion, Poros lemons, kontoules pears from the mountains of Corinth etc. Thus, they do not only contribute to the survival of small family farms, but also to the preservation and promotion to younger consumers of traditional, local (and Greek in general) goods as opposed to imported varieties and hybrids.

| Chervils, hartworts, wild rockets were completely unknown to consumers up until a few years ago. I’d tell them ‘take some and use it for your pies and you will thank me. That’s what kept us alive in villages’. Gradually, some started buying and now I can barely meet their needs. Especially younger housewives did not know of them, because they are no longer connected to their villages. Now they have begun to learn and come closer to nature

(Christos, producer from Viotia). |

But it is not only consumers who learn from producers, but the reverse too – a contact that highlights the social dynamics of this “live” interaction. Christos continues:

| Some housewives would not choose… say, irregularly shaped tomatoes and would only go for the ones that look round and clean. That means they shopped based on appearances. That made me look for specific seeds that give the fruit a homogeneous appearance. I spoke with agronomists, I read, I experimented with various seeds and the results were so impressive, that I sell everything out. I matched scientific knowledge with the experience gained from the market. My contact with people was what made me look further. In a sense, I became a small-scale commercial agent between the street market and the fields. |

In any case, the plethora of vendors, products and varieties seem to sustain competition at a level that is beneficial to consumers.

| There are many stalls and tonnes of displayed products. From a tonne of displayed watermelons, consumers will select the one they like. They feel rich enough to buy what satisfies their eye, to shop using their instinct. This is not the case in super markets… A large chain makes an agreement with a big-scale producer for a specific amount of products, based on their profit

(Vangelis, producer from Megara). |

The street market provides farmers with the option to sell directly to consumers, avoiding wholesalers and large distribution networks, thus improving their profit margins

| I used to sell in the central vegetable market and I am still owed money by merchants. Here it’s all cash in hand and even if I end up selling out for half price, I don’t face losses and I always gain. Merchants only want the best, they throw out whatever is not good for them and they pay whenever they want. For example, I can sell squished tomatoes for tomato sauce, here

(Marietta, producer from Thiva). |

The street market is a lively place bringing together different people, disparate at first glance, from a range of social groups: people living in the same neighbourhood that greet each other in the morning, small gatherings of idle pensioners, working people in a hurry, housewives shopping for the family’s weekly needs, lonely older people who buy the necessary for their meagre diet, low income and more affluent locals and migrants. The connecting links are the search for fresh, high quality food at an affordable price, chats with neighbours, relationships with the merchants, “cultural proximity” – albeit imaginary – with the place of production and with the producer.

As a familiar point of reference in the city’s neighbourhoods, street markets also operateas a space of political expression for citizens, a place for venting “popular anger” and sometimes, even mockery of politics and politicians, especially during the current crisis. They can serve as an inexpensive political barometer for the media that investigate issues such as surging prices, salary cuts, the faults of policies, the difficulties of everyday life.

Entry citation

Petrou, M. (2015) Street markets in the neighbourhoods of Athens, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/street-markets/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.52

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Σκιαδάς Ε (2014) Όταν γεννήθηκαν οι λαϊκές αγορές το 1929 για να χτυπηθούν οι κερδοσκόποι. Ο Μικρός Ρωμηός. Available from: http://mikros-romios.gr/laikesagores/.