The social profile of the city's waterfront and the real estate market

Maloutas Thomas|Spyrellis Stavros Nikiforos

Built Environment, Economy

2022 | Aug

The waterfront of Athens and the case of Vouliagmeni

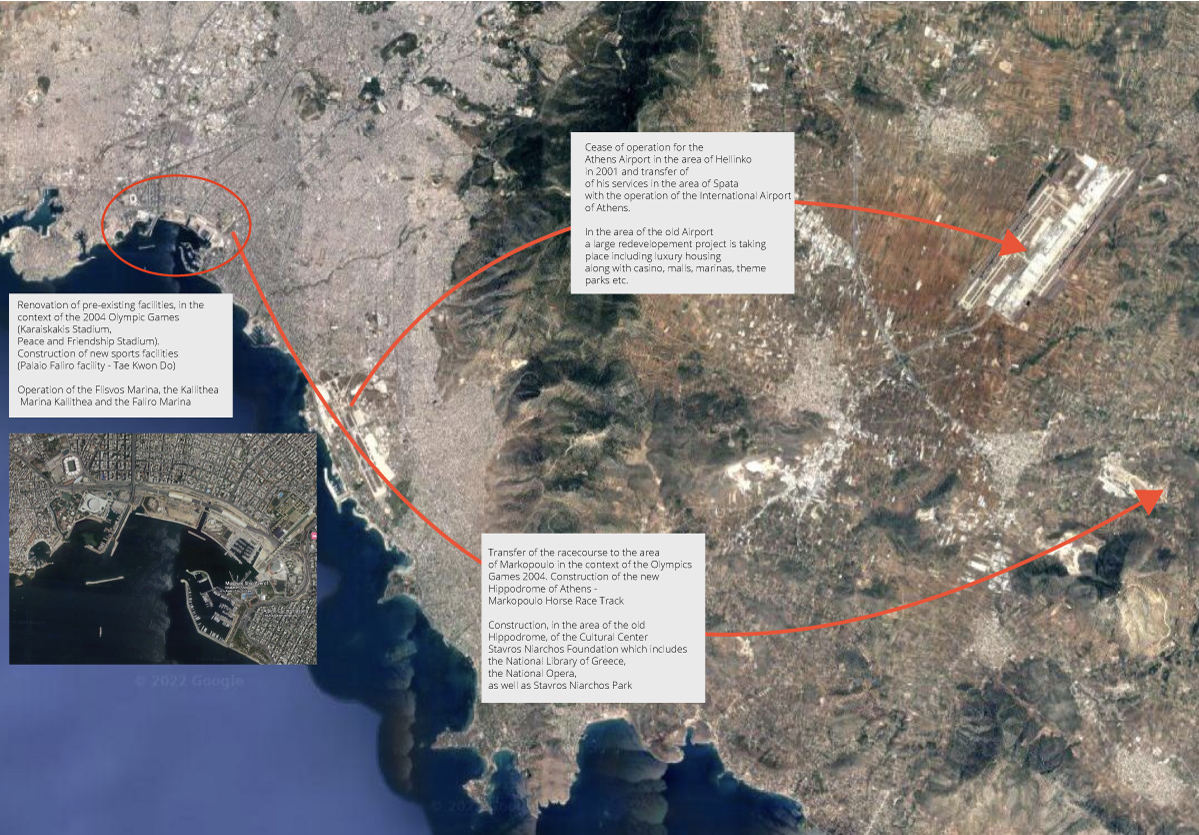

The capital traditionally had its back to the sea, and Piraeus –which always functioned as a separate unit– used the sea primarily for transport and trade. The waterfront has never been a focus of intense residential development for the capital. The area from Elliniko to Varkiza, i.e. the central part of the so-called “Athenian Riviera” (a term in the logic of realtor place branding), was sparsely populated until the 1980s and many of its settlement nuclei were not on the water. On the contrary, for many decades, large scale sports and other facilities were located in central parts of the waterfront –such as the old airport and the Hippodrome, which were moved to Spata and Markopoulo respectively, but also the Karaiskaki stadium (i.e. the home ground of the city’s biggest soccer team) and the Peace and Friendship stadium, which remain. The most central municipalities of the waterfront (Neo Faliro, Moschato Kallithea), also did not have their center on the beach. Even in Palaio Faliro, which was a recreational area with the sea as its central element, the dynamic of its residential development was fueled by the desire of the uprooted Constantinopulians of the 1950s to have the contact with the sea to which they were accustomed.

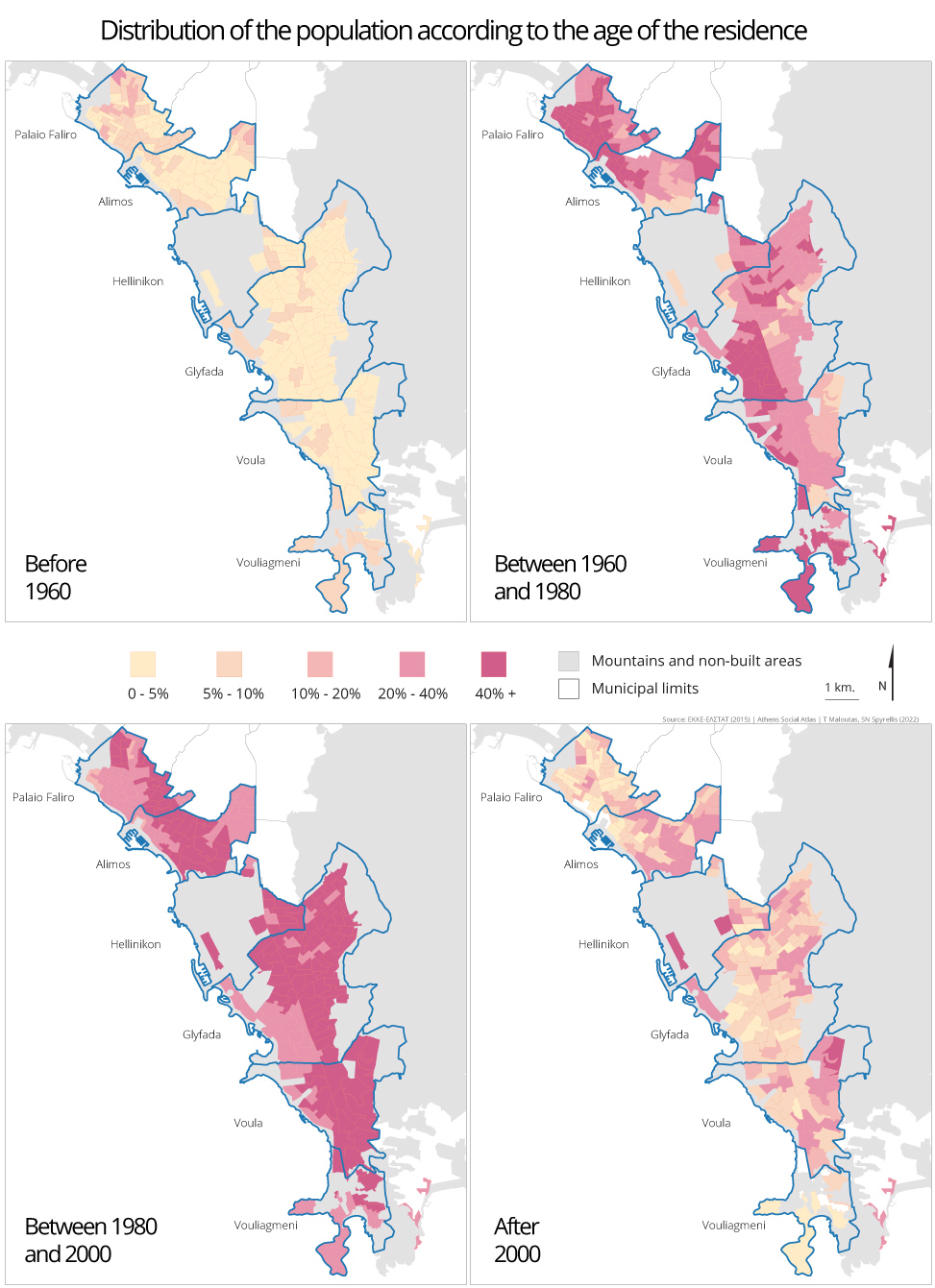

Maps 1-4: Distribution of the population according to the age of the residence

Source: ΕΚΚΕ-ΕΛΣΤΑΤ (2015)

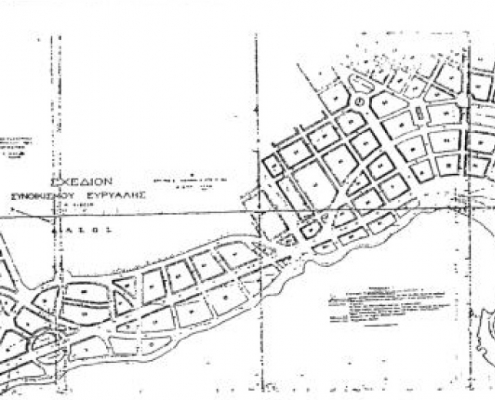

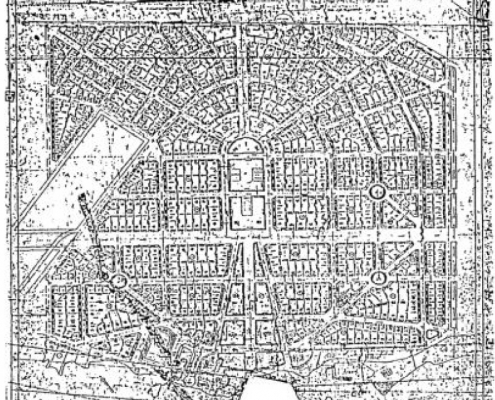

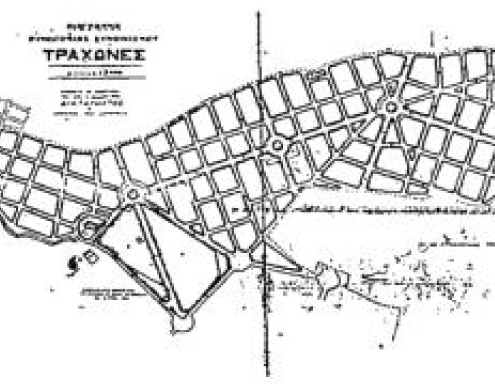

During the interwar period, private businessmen created suburban-garden-style settlements, with specific urban planning and architectural standards, in the suburbs of Athens. Τhe road network from Faliro to Vouliagmeni, which was built at that time, played an important role for the development of the necessary infrastructure of the coastal front. In 1922, the first plan was drawn up for the area of Evryali (Glyfada) which was expanded in 1925, while in 1926 the plan and building regulations were approved for the settlement of Alimos (Kalamaki), the settlement of “Trachones” (today’s Argyroupoli), and Voula. An exception is Paleo Faliro which was designed from the beginning (1880) as a resort. During the 1930s, building cooperatives were also established in the wider area, such as in the areas of Voula and Varkiza (see. Καυκούλα, 1990).

At the same time, the coastal front was never a place of mass suburban concentration of the high socio-professional groups of Athens, such as Psychiko, Filothei, Kifissia and Ekali. It used to be a vacation area with a relatively cross-class character, which gradually turned into an area of permanent residence. Its social profile was dominated by the middle classes, without a strong presence of working classes and with few and spatially localized concentrations of upper-class groups.

Maps 5-8: The plans of suburban-garden-style settlements

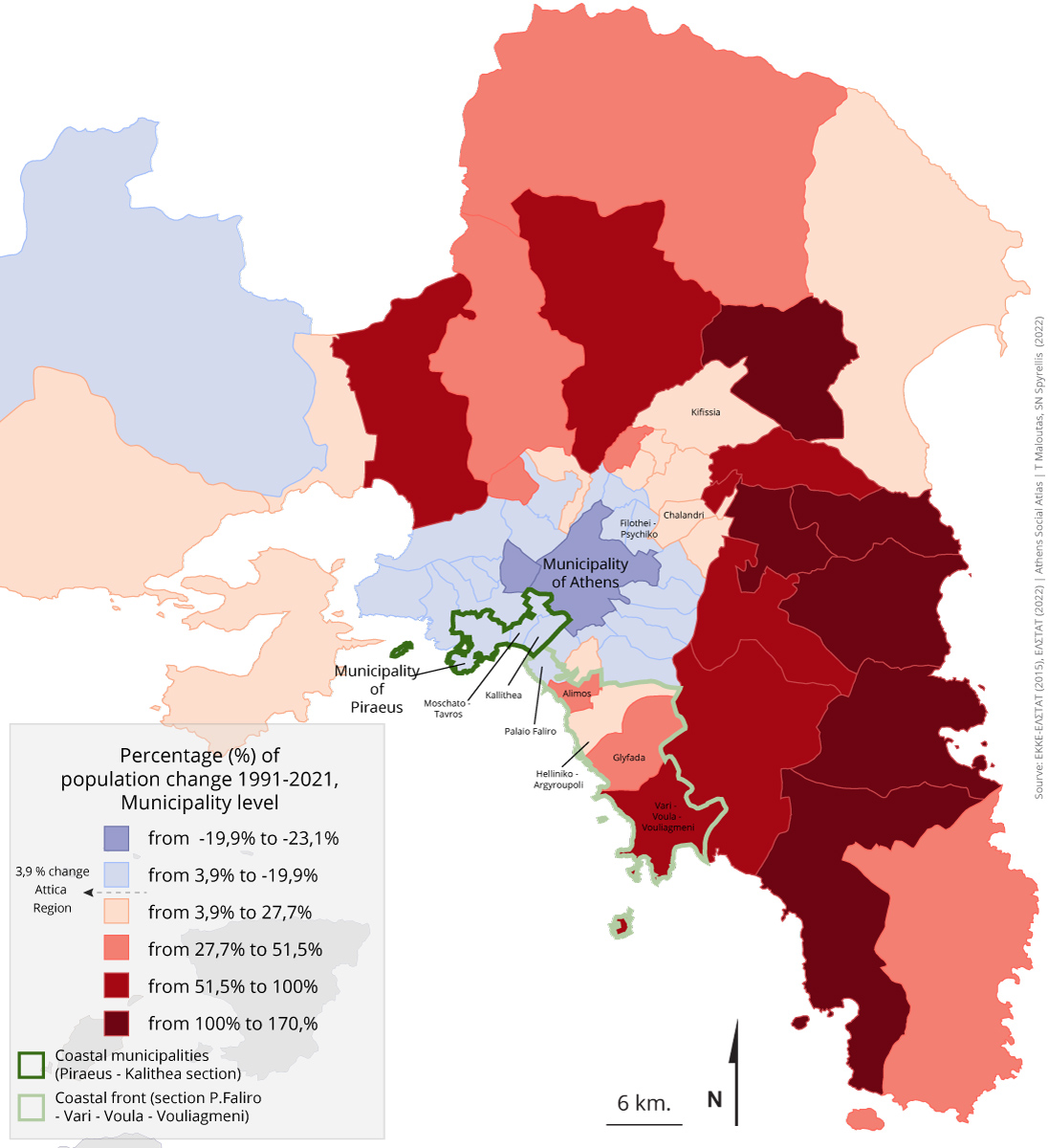

The evolution of the demographic and social profile of the city’s waterfront, compared to some other areas of the Athenian metropolis, is summarized in Table 1. Population-wise, the section from Faliro to Vari-Voula-Vouliagmeni shows a significant increase (+26%) in the period 1991- 2021, while the increase in the whole city was only 3.8%. In the other part of the waterfront (from Piraeus to Kallithea) the population decreased by 19% and in the center of Athens by 23%. With regard to the social profile, the waterfront municipalities from Paleo Faliro to Vouliagmeni show a significant ‘upgrade’ between 1991-2011, witnessed by the ration of the percentage of high professional categories –managers and professionals– in this area divided by the percentage of the same categories in the whole city. This trend is opposite to that recorded in all the other areas of the city listed in Table 1. The Municipality of Athens shows a significant decrease in the relative presence of high professional categories, which decreased from 1.21 times their average percentage in the city in 1991 to 0.92 times in 2011. Even the areas with the highest concentration of higher occupational categories –such as the Municipality of Filothei-Psychiko– register a decrease of their relative presence during the same period. Overall, there is a convergence of the social profile of the waterfront (from Faliro to Vouliagmeni) with that of the residential areas in the north-eastern suburbs of the city, where the upper and especially the upper-middle professional categories are mainly clustered.

Table 1. Demographic evolution of the coastal front of Athens (1991-2021) and change of the social profile (1991-2011)

Source: ΕΚΚΕ-ΕΛΣΤΑΤ (2015) for 1991 and 2011 and ΕΛΣΤΑΤ (2022)

Map 9: Demographic evolution in the Attica region (1991-2021)

Source: ΕΚΚΕ-ΕΛΣΤΑΤ (2015) for 1991 and 2011 and ΕΛΣΤΑΤ (2022)

Vouliagmeni, considered today a residential area of upper social categories, contains significant differences within it. The center of the community –on the western slope of the hill that separates it from Varkiza (Photo 1))– used to be scattered with wooden one-story holiday shacks that were gradually replaced by modern constructions. This part of the municipality was significantly altered during the dictatorship, when high-rise apartment buildings were built, often of low quality (Photos 2-3), driven by the large increase in the local construction coefficient (Photos 4-5).

The surrounding areas that were built later, i.e. the lower points on the two sides of the hill that separates Vouliagmeni from the communities of Vari and Voula (Photos 6-7), attracted newer upper-middle classes in maisonette-type units or small apartment buildings, as the construction coefficient had meanwhile declined and mortgage lending for such properties was out of reach for lower income groups. Upper social categories in the area have been clustering, for many decades, on the edge of the Kavouri peninsula (Photo 8) and, more recently, around the entrance of the “Alexandros Flemig” research center, on the small road that connects Vouliagmeni with Vari (Photo 9).

Photos 1-10: The residential development of the wider area of Vouliagmeni

A major stake for the future of the wider area is the privileged and undeveloped, until now, district of Fascomilia, along the coastal road that connects Vouliagmeni with Varkiza. Plans of the owner –the Church of Greece– to develop the area have been blocked several times by the municipal authorities and at a more central level. The transfer, however, of the development of the “Athenian Riviera” to the Fund for the development of public real estate property [ΤΑΙΠΕΔ] (Χατζηγεωργίου 2022) and the aggressive investment orientation of the New Democracy government for the “Piraeus-Sounio” coastal zone, create serious concerns for the environmental and social future of this piece of the coastal front of Attica.

If the future of the unbuilt Fascomilia is still at stake, there are many other developments in recent years that clearly show the direction things have taken in the city’s waterfront.

Changes in the real estate market

Construction activity, which had been limited for many years, has been strongly revived recently. This involves new buildings on the outskirts of the coastal communities, but mainly the construction of luxury apartment blocks (often with a private pool per apartment) replacing older holiday homes and small apartment buildings. This activity is vibrant in Vouliagmeni, Voula, Glyfada, Varkiza (Photos 11-22). For example, in a small street in Vouliagmeni, second parallel to the coastal avenue, where there was no construction activity for many years, three new buildings are erected at the same time along with many renovations within five small building blocks.

Photos 11-22: New constructions in Voula and Varkiza

The new constructions give the impression of an environmentally sensitive architecture –something that is not necessarily the case– which follows a pattern of impersonal buildings for everywhere and nowhere, unrelated to the context that surrounds them. Moreover, these buildings clearly foster the isolation of their residents from their natural and social surroundings. The living area of the residence is visually isolated and fortified against the street with high retaining walls and other physical barriers to safeguard persons and property, while it is also distanced from the sea, which is functionally replaced by the private swimming pool and functions as a backdrop. Islands of residential luxury [1] are thus built for those who can afford them (Photos 23-28).

Photos 23-28: New luxury residences in Vouliagmeni and Glyfada

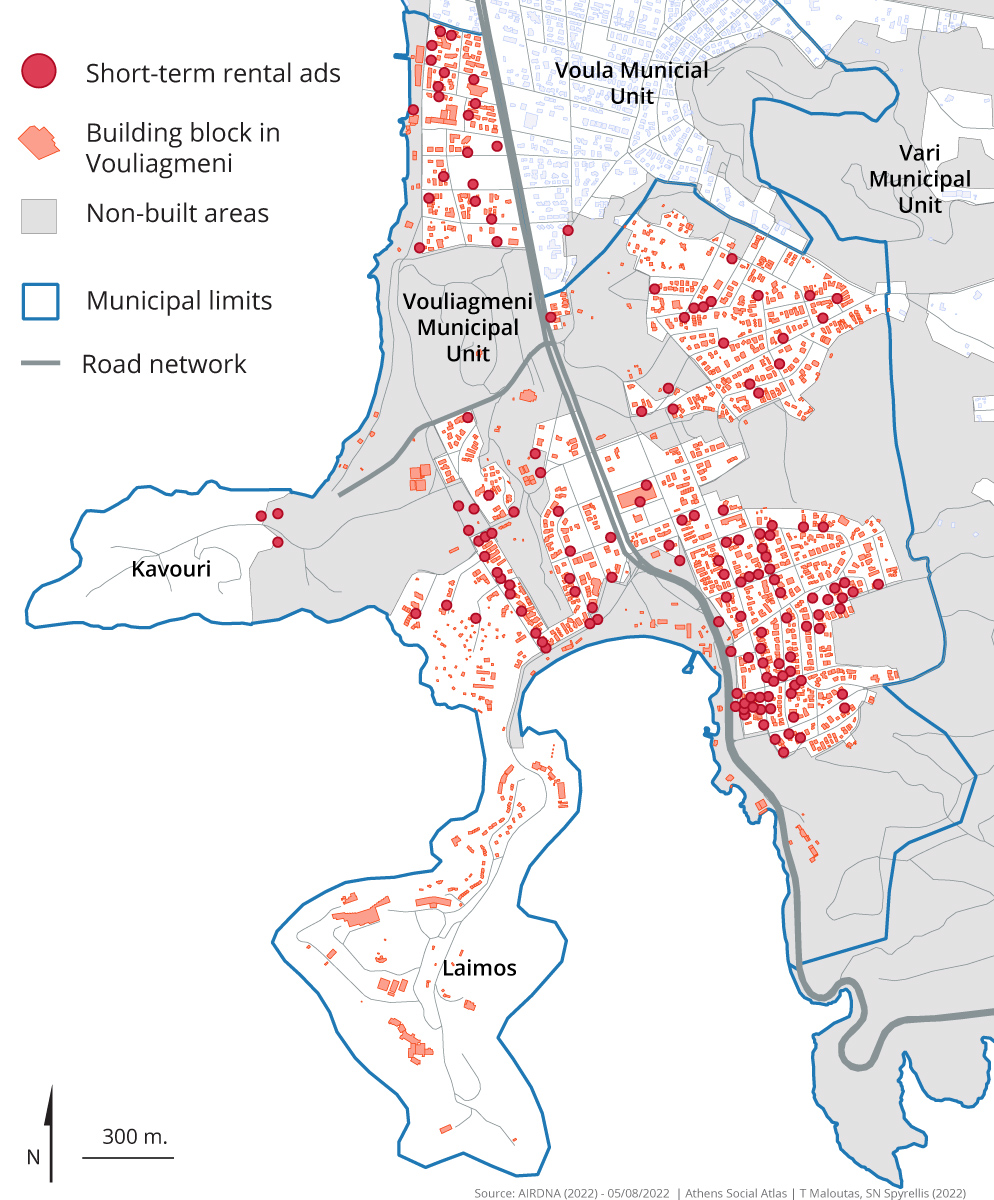

Map 10: Spatial distribution of short-term rental ads in Vouliagmeni

Source: AIRDNA.co, 5/08/2022

Increased construction activity is obviously related to increased demand. This involves domestic demand from affluent households who choose to move to the beach –recently also as a result of the pandemic– but mainly concerns demand from abroad. The latter includes the demand for touristic short-term rental, as well as for longer-term rental (that of digital nomads, for example) or for investment aimed at exploiting the increased demand for accommodation in the area. The increased demand on the waterfront is reflected in the map of short-term rental ads and in the smaller demand curve on the coast compared to the rest of the metropolitan area (Ρουσάνογλου 2022). At the same time, the presence of demand from abroad emerges through many micro-stories: in a small family apartment building with five apartments built in 1966, in the centre of Vouliagmeni, two of them were sold by the original owner (the first in the 1970s and the second in the 2000s) to the same Greek buyer, who used them for his family’s holiday home and long-term investment.

After 50 years of stable ownership and own use, this small block of flats experienced increased mobility in transfers, number of users and ethnic diversity. The heir to the buyer of the two flats, sold them in 2017: one to a young Egyptian real estate professional, London resident and golden visa holder, who is trying to rent it out on the short-term and/or fixed-lease market, and the other to a Lebanese investor, who in turn sold it to a Chinese investor who is trying to capitalize on it through a Cypriot property management company. The remaining three apartments belong to the family of the heiress of the original owners, with the large upstairs apartment occupied by her and her husband for 45 years, the ground floor serving as a warehouse, and the first floor apartment occupied since 2021 by a German journalist permanently settled in Greece. This apartment was renovated in 2018, several years after the death of the owner’s parents who lived there for many years, and after a brief attempt to operate it on a short-term lease. Similar stories can be found in many buildings in the area that are now entering the new rhythm of the market, even if they do not seem to meet the conditions (Photos 29-30).

Photos 29-30: Old constructions at the current pace of the real estate market in Vouliagmeni

The housing stock on the coast of Athens was in the hands of the city’s middle classes, with varying social profiles by area. It was an owner occupied vacation area that was progressively converted into a permanent residence area, remaining however –if not in the hands of the same owners and users– socially in the hands of the same clientele. The presence of the upper social categories was sporadic and relatively discreet, in the sense that they acquired privileged properties, but mainly for private use and not for commercial exploitation. Even the large hotel investments in the area –such as Asteras Vouliagmenis– had, despite their elitist profile, a public character that did not create multiplying effects of social exclusion in the surrounding areas.

In recent years, especially from 2016-17 onwards, the situation has changed significantly with real estate properties transforming from (mostly) use values to quick payback and easy profit investment products. This has increased mobility in the housing market, with the changes of the last period intensifying the social divisions that mortgage lending promoted in the 1990s. Housing loans during that period drove up property prices and led to the gradual exclusion of the lower and lower-middle classes from access to home ownership in most areas of the city. What has emerged –and which is expected to intensify much more in the coming years– is the change in the social profile of the waterfront, characterized by increasing social exclusion not only from housing, but also from public goods and services in the area.

Access to goods and services in the coastal zone

The increased demand for the beach front is also confirmed by the increased flow of young people for activities at sea. The familiarization of the Greek population with the sea as a pole of attraction for leisure activities and recreation took some time and came from abroad, despite the location of the country and the seamanship of many Greeks. The latter, however, concerned specific places, created a professional relationship with the sea and was not contagious. Today, when a strong southerly wind blows and waves rise in the bay of Vouliagmeni, dozens of young people appear in full gear –black isothermal suits, windsurfers, surfboards and towing eagles– regardless of the season (Photo 31). However, their free access to the sea is now limited to a small piece of coast between the main beach and the Marine Club of Vouliagmeni, with very problematic parking and with half of this free piece of coast granted to a private operation renting sunbeds (Photos 32-33).

Photos 31-33: Access to the sea

Traditional free access to the sea is now close to disappearing. Few spots in the bay of Vouliagmeni can be used free of charge and access to them is impossible for people with mobility problems. Parking has become very difficult, as near the beach all the relevant spots have been turned into private parking lots of the restaurants and privatized coasts near them. On weekends it is almost impossible to find a table without a reservation in the restaurants and all day lounges on the waterfront and without using their team of valets, reminding the unleashed private organization of dining or taking a coffee in Istanbul’s Ortaköy. Most restaurants on the beach. Most restaurants on the beach are expensive (a kilo of fresh fish ranges from €65 to €120) but they are much less expensive than those within or next to the Asteras Vouliagmenis resort. Cheaper dining options exist on the side street of the avenue and next to the main Vouliagmeni Square, with a more affordable choice of a well-known souvlaki joint and a more modern version of it. Among the more affordable options is an old patisserie-restaurant, operating since the 1970s when its owner won a lottery and financed his business. Today this old restaurant follows the standards of a previous era and mainly caters to the elderly. In the same area, different new joints compete for the growing clientele. New brunch shops promoted by lifestyle magazines, faceless all-day bars, family ice cream parlors and an old tavern from the 1960s trying to survive without changing radically (Map 11). The survival of businesses providing leisure services is very competitive at this level– as witnessed from the limited lifespan of many units– while competition is almost non-existent for services aimed at the top level of consumption.

Map 11: The Vouliagmeni commercial network

Source: On-site research

The investments in Asteras Vouliagmenis and Elliniko

The new investment in Asteras Vouliagmenis with funds from Kuwait, Abu Dhabi and Turkey has given a Middle Eastern flavor to the services it offers (Photo 34) but that’s just the icing on the cake. The essence lies in the new products and the way it offers them. The basis for the investment is both the natural beauty of the area, as well as the history of continuous service to the Athenian, as well as the international, elite since the end of the 1950s (Νένες 2021). In relation to the past when the social exclusion from Astera’s services was done more on the basis of social and cultural standards, the new exclusion is built with the inaccessible economic limits. The cost of a night’s stay in the cheapest rooms of the two hotels renovated by the consortium is much higher than the basic salary and is roughly at the same level as the monthly rent of a renovated 80 square meter apartment in central Vouliagmeni. In the waterfront area facing the Saronic Sea, where the complex’s third hotel was demolished, the consortium is building 13 villas valued at €50 million each and a central pillar of investment in the area’s real estate market (Photo 35). On the other side of the peninsula, facing the bay of Vouliagmeni, the consortium is reshaping and expanding the marina by extending the jetty and deepening its bottom to accommodate more and bigger boats (Photos 36-37), despite the objections of local actors and environmental organizations as concerns the impacts on the viability of the bay.

The type of investment has given a specific character to the rest of the complex’s services. The restaurants of Asteras address a demand that does not concern, to a very large extent, the residents of the city. At “Pelagos” the nine-course tasting menu costs 260 euros, including drinks. At the Japanese Mathuhisa, most hot dishes cost around €50, except for lobster or a special filet which costs twice as much. Entrance to the beach of Laimos – which was never cheap and cost many times more than the entrance to the “popular” beach of Vouliagmeni – is today prohibitive for most people: € 80-100 on weekdays for an umbrella with two sunbeds and double the amount on weekends, while admission for each child adds €15 on weekdays and €25 on weekends. Inside the beach there is also a gradation of where one sits based on what one pays (Photo 38) – thus teaching the younger generations about how life (should) be.

Photos 34-38: The investments in Asteras Vouliagmenis

The lake of Vouliagmeni, with a water temperature that allows even non-winter swimmers to swim all year round, is also expensive for those who would like to visit it often (€15 on weekdays and €18 on weekends and holidays, while on the premium side of [wooden edge] the daily ticket for two people is € 60 on weekdays and € 80 on weekends). Now, the entrance to the “popular” beach is not cheap for a family with a low income (€ 10 on weekdays and € 15 on weekends and a package of € 35 for a family of four with two children up to 15 years old). The municipal authority proposes lower prices (€ 7.5 instead of € 10) but the managing company (ETAD SA) insists that it determines the pricing policy based on the statute and the directions of its shareholder. The entrance to the beach of Voula is a little cheaper (€ 7 on weekdays and € 8.5 on weekends) while the use of umbrellas and sunbeds has an additional cost in both. Varkiza beach has similar entry prices, while slightly cheaper options are available at Alimos beaches. However, the very high prices concern many points along the entire length of the beach front (such as Lagonisi), while the beach bars that drag the dance of the expensive beach are spreading more and more (https://www.nou-pou.gr/paralia/poso-stixizei-fetos-i-eisodos-noties-paralies/).

The investment in Asteras of Vouliagmeni has indirect effects, due to the neighborhood, on the surrounding community, such as for example the very high prices of small hotels in the area which are due much more to the location and not necessarily to what they offer (Photo 39). The Asteras consortium also intervenes directly, financing, for example, the reconstruction of the central square of the municipal community (Photo 40). In this way, it signals the interest in surrounding the investment and in creating a positive climate with the municipal authority for its controversial plans, such as the expansion of the marina.

Photos 39-40: The indirect and direct effects of the investment in Asteras of Vouliagmeni

The investment in Elliniko predicts much larger changes for the waterfront, in a similar direction, even if almost nothing has yet materialized. The developer’s (Lamda Development) plans for luxury housing along with the casino, the malls, marinas, theme parks and all the paraphernalia –like the plans of Athens College (I.e. the traditional private school for children of the elite) to establish a branch in Elliniko– outline the overall effect that such investments will produce. The aspiration is not limited to profit, but involves the creation of an urban environment whose consumption (by those who can afford it) becomes an end in itself, disengaged from the object of consumption itself. The process becomes a pleasurable experience embedded in a guilt-free lifestyle, detached from those who can’t have it. The ad of Lamda’s recent green bond, from which it raised €230 million, portrayed a young generation growing up and living the important moments of their adulthood in the safe and sterilized world of shopping malls, private colleges, and the environmentally sensitive and technologically advanced living space, which, at the same time, is a milieu of social blindness.

Map 12: Big projects on the waterfront

Source: Google maps

Thus, while the effects of the investment in Elliniko have not appeared yet, their direction is already clear. Moreover, the other smaller investments recently made in the area have already affected the social fabric. Schools in Vouliagmeni –especially secondary schools– used to be ignored by the local affluent households who sent their children to private schools, even they had to travel very long distances daily. This is reflected in the relatively low performance of the candidates from the local Lyceum in the exams to access universities in 2005 (Map 13) [2]. Today, the population of the municipality has increased as well as the demand for the local schools. The social profile of this demand also changed, as can be witnessed from the cars of parents waiting to pick up students every noon. Overall, the cars in Vouliagmeni have changed, and the presence of a Bentley or an Aston Martin is not surprising any more. Even the tragic accidents in the area materialize with vehicles that are not common. Last year, the brother of a politician was killed driving a Ferrari on the waterfont avenue, and a popular rapper was killed driving a Porsche in the center of Vouliagmeni.

Map 13: Location of secondary schools (Lykeia) by type and performance

Source: Maloutas et al (2019)

The future of the waterfront

The middle classes that dominated the broader area are becoming, more and more, spectators in the upgrading of the coastal region, following the investment in products and services that increasingly exclude them. Some of them, with larger real estate assets, can withstand and possibly benefit from these changes. However, many of them are gradually alienated from their neighborhoods, which no longer offer the kind of services they want, nor the price level they can afford. Gentrification is not only about the displacement / exclusion of low-income groups. It can operate at different social levels and the same groups that are gentrifiers in some areas may be the victims in others.

The unregulated real estate market is turning housing into real estate investment products in parts of the city that attract the most demand. The effects go beyond the deepening of social segregation and the displacing of old residents from their neighborhoods. The areas of the city experiencing the strongest demand are turned into theme parks where functional mix (ie the mixing of different activities) and social mix are obliterated. This brings in the problems well-known to functionally one-dimensional and socially homogeneous areas. The unregulated market obviously does not offer socially just and environmentally sustainable solutions. But it can provide super profits to the few who can take advantage of the business opportunities offered by increased demand and, at the same time, stimulates their ideological commitment to economic liberalism and raises their capacity to govern their political supporters.

[1] Carlucci et al. (2020) used private swimming pools as a measure of social segregation between residential areas in Athens.

[2] Based on the analytical data on the performance of the graduates of the year 2004-05 in the Pan-Hellenic exams, the High School of Vouliagmeni was in a low position among the High Schools of Attica (Maloutas et al, 2019).

Entry citation

Maloutas, T., Spyrellis, S. (2022) The social profile of the city’s waterfront and the real estate market, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/the-athenian-riviera/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.108

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Carlucci M, Vinci S, Lamonica GR & Salvati L (2020) Socio‑spatial Disparities and the Crisis: Swimming Pools as a Proxy of Class Segregation in Athens, Social Indicators Research, 161, 937–961 (https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s11205-020-02448-y.pdf)

- ΕΚΚΕ-ΕΛΣΤΑΤ (2015), Πανόραμα Απογραφικών Δεδομένων 1991-2011. Διαδικτυακή εφαρμογή για την πρόσβαση και χαρτογράφηση κοινωνικών δεδομένων, διαθέσιμο από: http://panorama.statistics.gr/.

- Maloutas T, Spyrellis SN, Hadjiyanni A, Capella A, et Valassi D. (2019) « Residential and school segregation as parameters of educational performance in Athens », Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography [En ligne], Espace, Société, Territoire, document 917, mis en ligne le 23 octobre 2019, consulté le 23 août 2022. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/cybergeo/33085 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/cybergeo.33085

- Καυκούλα Κ (1990), Η περιπέτεια των κηπουπόλεων, Διδακτορική Διατριβή, Αριστοτέλειο Πανεπιστήμιο

- Νένες Γ (2021) Αστέρας Βουλιαγμένης: Η ιστορία του θρυλικού συγκροτήματος, Athens Voice, 22/07/2021 (https://www.athensvoice.gr/life/life-in-athens/722816/asteras-voyliagmenis-i-istoria-toy-thrylikoy-sygkrotimatos/?fbclid=IwAR110ASr7fnpfOHL-7H650hXqCN7c0-KmNPdaofoR_tSoC-vXIWNh4T_lIM)

- Χατζηγεωργίου Α (2022) ΤΑΙΠΕΔ και οικοπεδοποίηση των «παραλιακών φιλέτων», Εφημερίδα των Συντακτών, 12/04/2022, (https://www.efsyn.gr/ellada/koinonia/339579_taiped-kai-oikopedopoiisi-ton-paraliakon-fileton)