2020 | May

Today that the COVID-19 pandemic has emerged as the most significant public health issue of our time, historical knowledge of how societies have dealt with pandemics in the past is invaluable in dealing with the current crisis. Indeed, in addition to medical science, history too is an essential tool that sheds light on the experiences of the implementation of decisions and policies adopted in the past to tackle other epidemics and pandemics. Historians have studied the mortality caused by various diseases over the years as well as the effects of diseases and epidemics on the longterm health of people and, of course, on society as a whole. When an epidemic broke out, it caused not only human pain and suffering but also panic and threw the social and economic structure into disarraydisrupting growth and development in affected areas. In other words, the very mechanism that we are seeing in action today has already been studied extensively and we should thus be more familiar with it.

This article outlines my 2018 study [1] on the Spanish Flu in Athens, complementing it with spatial depictions [2] of the deaths attributed to the Spanish Flu in the Greek capital during 1918.

There have been numerous studies in recent years on the so-called Spanish Flu [3] of 1918, its death toll of approximately 50 million people and its impact on the public health of countries involved in World War I, yet the issue is absent from the Greek historical record. This doesn’t mean that the influenza did not reach Greece or that it didn’t claim victims in the country; however, during that same period, other infectious endemic diseases, such as tuberculosis, typhoid fever and malaria, were causing significantly more deaths.

Indeed, the level of public health was particularly low during the Interwar period and was characterised by high infant mortality (148‰ during 1920-24, compared to crude death rate for that period (Valaoras 1959) of 21.2‰).

During the second decade of the 20th century, public healthcare facilities in Athens were still rudimentary. In the entire Municipality of Athens, which had a population of 300,000, just three out of a total of 12 hospitals functioned as general hospitals.

The Spanish Flu in the Greek historical record

Fokion Kopanaris, Director of Hygiene at the Ministry of Hygiene from 1912, mentions the Spanish Flu in his 1933 book Public Health in Greece (in Greek; original title: Η δημόσια υγεία εν Ελλάδι), but he does so only in passing:

| “The largest of the influenza epidemics in Greece was that of 1918, during which the disease reached pandemic proportions. During that global epidemic, in Athens alone there were 1,668 fatal cases, and in Thessaloniki 5,284.” (Κοπανάρης 1933) |

The author offers no further comment on the number of dead. Beyond Thessaloniki, however, Patra too recorded approximately 500 victims (95 deaths per 10,000 residents) because of its port.

The influenza appeared in Greece in the summer of 1918, and its first victims in the capital were recorded in September. Yet in October 1918, the Ministry of the Interior, to which the Public Health Service belonged, stated that it had no intention of implementing any special measures and that

| “individuals must themselves take the recommended precautions. And these come together in almost one thing: Avoiding gatherings. This is the only remedy. Garlic, ouzo and other nostrums claiming to prevent the influenza are comical…” (Embros Newspaper, 17 October 1918). |

When the public heard about the discovery of the Viennese Professor Scheiller “that the cause of the influenza is streptococcus, which can safely be destroyed by injecting a solution of mercury chloride (sublimate),” the Minister “ordered that the Medical Council, the Iatrosinedrion, convene as soon as possible to determine how to use the recommended medicine.” However, University of Athens professor and Iatrosinedrion member Menelaos Sakkorafos showed restraint, stating:

| “I ought to remind that mercury—because this is about mercury—is a drug that requires normal kidney and liver function. Unfortunately, this year’s influenza has complications involving mainly the kidneys and therefore the use of mercury demands the utmost care as it is most likely to cause harm.” (Embros Newspaper, 24 October 1918). |

To be sure, the Viennese “discovery” did not yield the expected result, and the Greek state tried to adopt measures to contain the spread of the disease.

At the same time, experts informed the public about possible complications resulting from the use of injectable mercury and pointed out the susceptibility of the working classes.

The epidemic continued to spread throughout the autumn; schools, cinemas, theatres and cafés closed, and special hygiene measures were implemented. Nevertheless, there was a sharp increase in the number of victims in November and December.

| “The soldiers and civilians that died of influenza in Athens according to the statistics of the Ministry of the Interior numbered 595 in October, 650 in November, and in December, until the day before yesterday, 259. During the past 24 hours, seven people have died of influenza.” (Embros Newspaper, 30 October 1918). |

Municipality of Athens death certificates for 1918

There are no statistics on causes of death in Greece prior to 1921. Concerning the capital specifically, there is also a lack of statistics on the annual number on deaths and births for the period leading up to the publication of the Statistics of Natural Population Movement report of 1921, which was the first such report to be published since 1885. Thanks to a study published in 1926 , by Trifon Andrianakos (1855-1966) (Ανδριανάκος 1925), a physician and later professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at the University of Athens, we know the number of deaths for the period 1914-1923. In 1918, in the Municipality of Athens, which had a population of approximately 300,000, there were 9,257 deaths (5,335 males and 3,922 females) compared to 6,354 in the previous year—a 45% increase—meaning that as result of the influenza epidemic the crude death rate for 1918 reached 33.06‰. The epidemic subsided in 1919, and the total number of deaths in 1919 was significantly lower than in 1917, as all vulnerable, high-risk residents had already died (Table 1). As evidenced by the thoroughly indexed death certificates of the Municipality of Athens for the first five months of 1919, the epidemic did not resurge (Figure 1). It also did not resurge in Athens in 1920, despite doing so in other countries including neighbouring Bulgaria.

Table 1: Deaths and crude death rates in Athens, 1916-1920

Source : (Ανδριανάκος 1925)

Figure 1. Monthly distribution of deaths in the Municipality of Athens, January 1918-May 1919

Source: Municipality of Athens death certificates

The classification of causes of death for 1918 (Table 2) highlights the prevalence of epidemic, endemic and infectious diseases, which constituted the foremost cause of death and were responsible for approximately half of all deaths; the capital was still in a pre-epidemiological transition stage. Diseases of the digestive system still caused 12% of deaths, and diseases of the respiratory system, such as pneumonia and pleurisy, caused 10%.

Table 2: Causes of death in Athens in 1918 (classed as per the 1920 revision of the International List of Causes of Death)

Source: Municipality of Athens death certificates

However, if we further analyse these 15 broader categories and classify diseases into the 38 more specific categories named in the 1920 revision of the International List of Causes of Death (ILCD3), we are able to better examine the state of public health in Athens and, of course, the impact of the influenza of 1918.

Comparing the two charts (Figures 2 and 3), we can determine that despite the ongoing influenza epidemic in October, November and December 1918, the hierarchy of diseases that caused the greatest number of deaths remained unchanged and that tuberculosis, along with the other diseases of the respiratory system, and the diseases of the digestive system remained the leading causes of high infant and child mortality.

Figure 2: Causes of death accounting for more than 2% of deaths in the Municipality of Athens in 1918 (classed as per the 1920 revision of the International List of Causes of Death)

Source: Municipality of Athens death certificates

Figure 3: Causes of death accounting for more than 2% of deaths in the Municipality of Athens during the three months (October, November and December) of the epidemic of 1918 (classed as per the 1920 revision of the International List of Causes of Death)

Source: Municipality of Athens death certificates

Figure 4: Age and sex distribution of individuals who died in Athens in 1918 (%)

Source: Municipality of Athens death certificates

Of the 9,296 deaths in 1918, 57.6% were males and just 42.4% females (Table 3 and Figure 4). This is normal considering the sex composition of the population of Athens in the two censuses that were carried out in the early 20th century: males comprised 54% of the population according to the 1907 census and 56% according to the 1920 census. The population of the capital was young and predominantly male, due to the unwed migrants as well as the soldiers and military officers that were recorded in the city. The ages recorded at time of death and possible interpretations of the mortality trends within each age group were examined in the original 2018 study; the following focuses on the victims of the Spanish Flu based on the civil status documents.

Influenza victims in Athens

A little more than one third of the victims of the influenza of 1918 died in October (616 of a total 1,726; i.e. 35.7%) and another third in November (634; i.e. 36.7%), and by December the epidemic had waned to half its earlier intensity, claiming just 16% of total victims (the remaining 12% distributed over the previous months) (Figure 5). The epidemic tapered off without returning to claim new victims in March 2019 as it did in other countries. Greece, and particularly Athens, was hit by the so-called second wave of the pandemic, that of autumn 1918, but was spared by the third.

Figure 5: Monthly distribution of influenza deaths in Athens in 1918 (%)

Source: Municipality of Athens death certificates

According to the Municipality of Athens death certificates, one in five of the people who died in Athens in 1918 died of influenza, with the vast majority of them being male (62.7%) (Table 3).

Table 3: Age and sex distribution of influenza victims in Athens (%)

Source: Municipality of Athens death certificates

The influenza of 1918 appears to have impacted mostly adult men, but it also had considerable impact on vulnerable groups such as children under five years of age and elderly people over 60 (Table 3). Its victims were primarily soldiers and officers as well as those segments of the capital’s economically active population that came into close contact with colleagues in the workplace where the disease spread as easily as it did in schools, universities and barracks.

More than half of the male victims of the influenza epidemic were school and university students and, mostly, soldiers and officers (Table 4). The rest of the victims were craftsmen and shopkeepers and their employees. Few victims belonged to the professional categories associated with the Athenian elite, just enough to remind us that the members of the elite avoided the crowded public spaces that were the main transmission hubs of this epidemic.

Table 4: Socioprofessional classification of male victims of the 1918 influenza in Athens

Source: Municipality of Athens death certificates

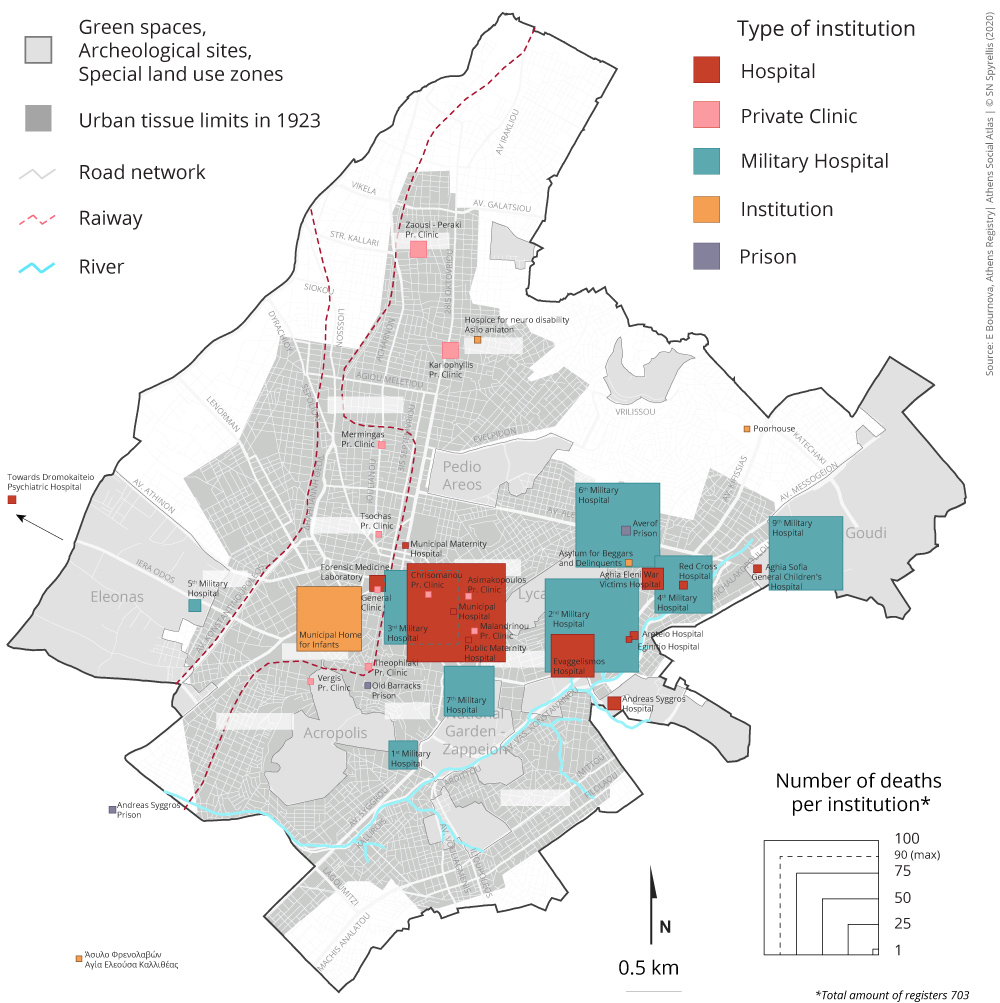

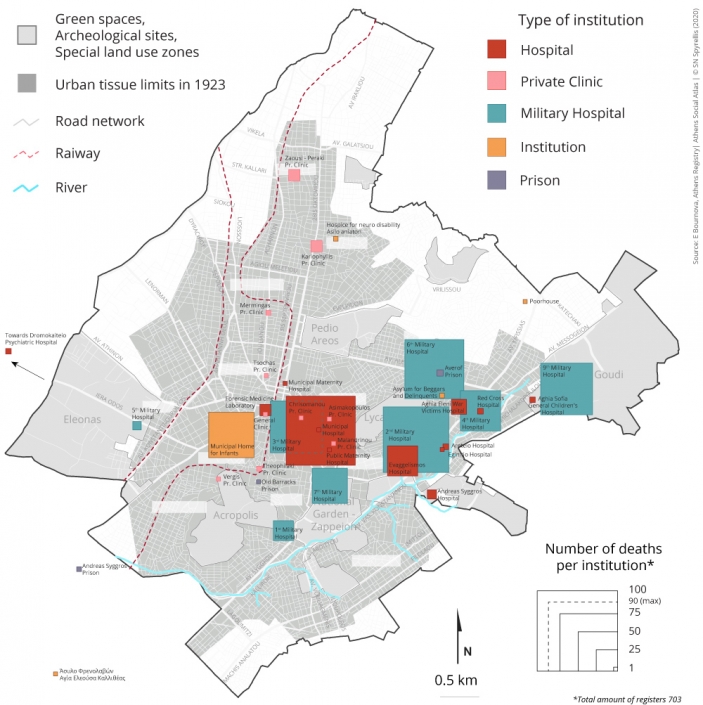

In contrast to female victims, half of all males who died of influenza died in hospital, and three quarters of these (395 of a total of 530) were mostly soldiers or unemployed, university students, artists, and members of the clergy. Soldiers and officers died in the 12 military hospitals that existed in Athens at the time, not all of which were healthcare institutions with permanent facilities: some were temporarily housed in other public buildings or were makeshift shelters put together to meet the healthcare needs of the war wounded and those suffering from influenza. Of course, most of these had easy access to the army barracks in Goudi. The remaining quarter of males who died in hospital were serving in security and law enforcement, working as artisans-craftsmen, or employed as labourers (Map 1). The large number of victims recorded in the various residential institutions for vulnerable individuals—such as the Home for Infants, the Home for the Terminally Ill, the Poorhouse, and the Asylum for Beggars and Delinquents—indicate that there were no isolation protocols in place to limit the spread of the virus.

Map 1: Distribution of deaths according to place of death (institution)

Source: Municipality of Athens death certificates

Approximately two out of three female influenza victims (71%) were aged 10 or older (Table 3), and of these, four out of five (83%) were listed as “housewives” on their death certificates (Table 5). Almost two dozen were listed as maids, 14 were listed as schoolgirls, and a handful as prostitutes, labourers and seamstresses; just two were listed as having non-manual occupations: a handicraft instructor and a pedagogue. Just 18.6% of the female victims died in hospital, and these were almost exclusively maids, prostitutes and labourers who were not originally from Athens. Housewives died at home, because even though most of them hailed from other regions, they had settled and established families in the capital.

Table 5: Distribution of female influenza victims aged 10 or older by occupation, place of death and place of origin

Source: Municipality of Athens death certificates

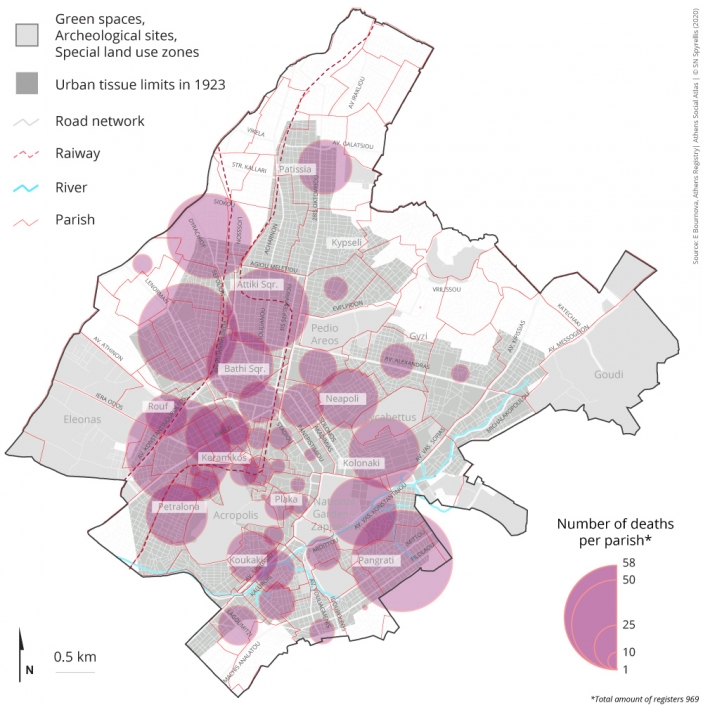

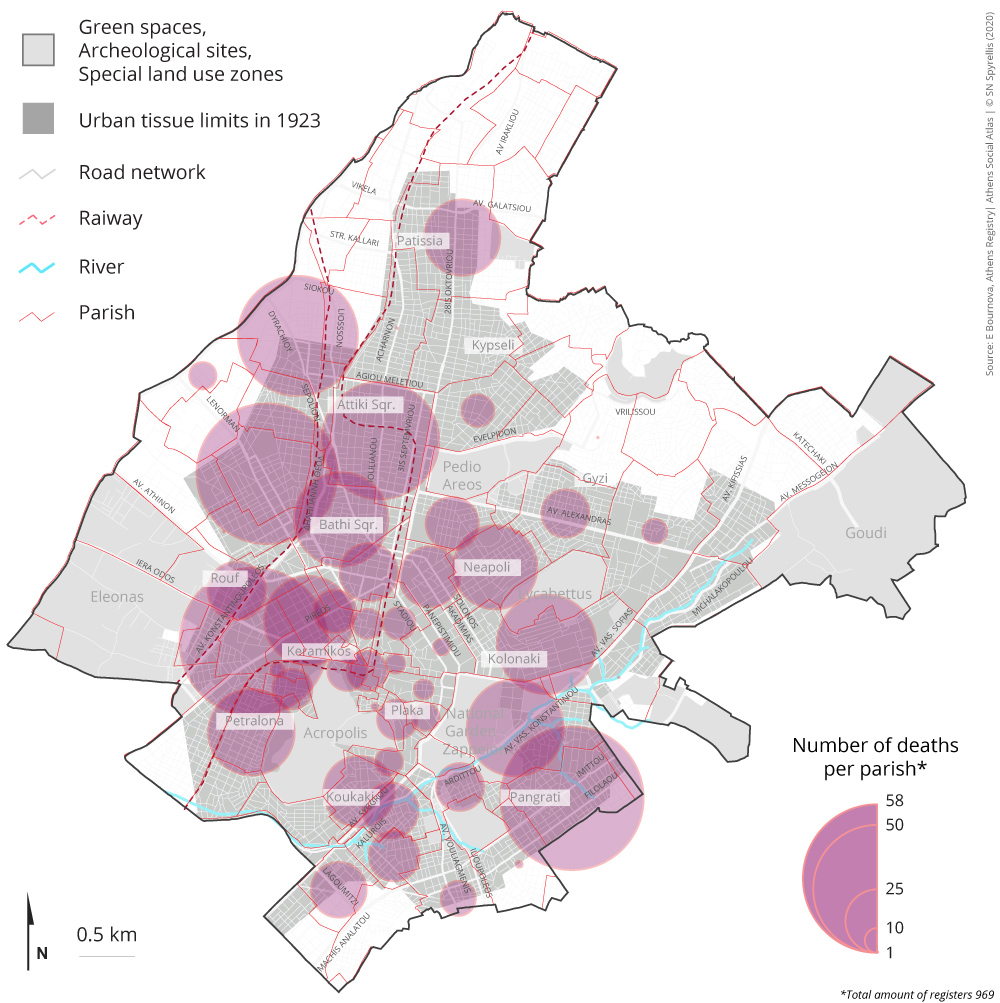

Map 2: Distribution of deaths according to place of death (parish)

Source: Municipality of Athens death certificates

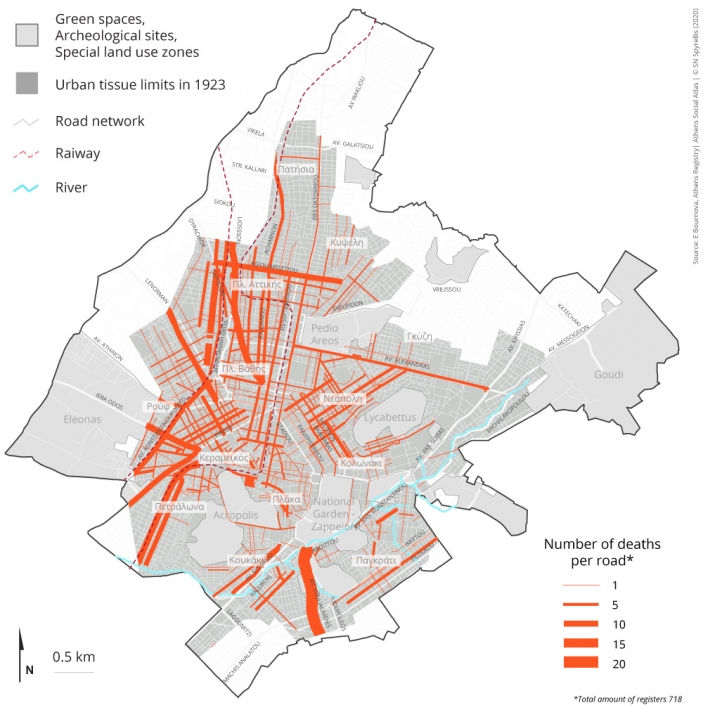

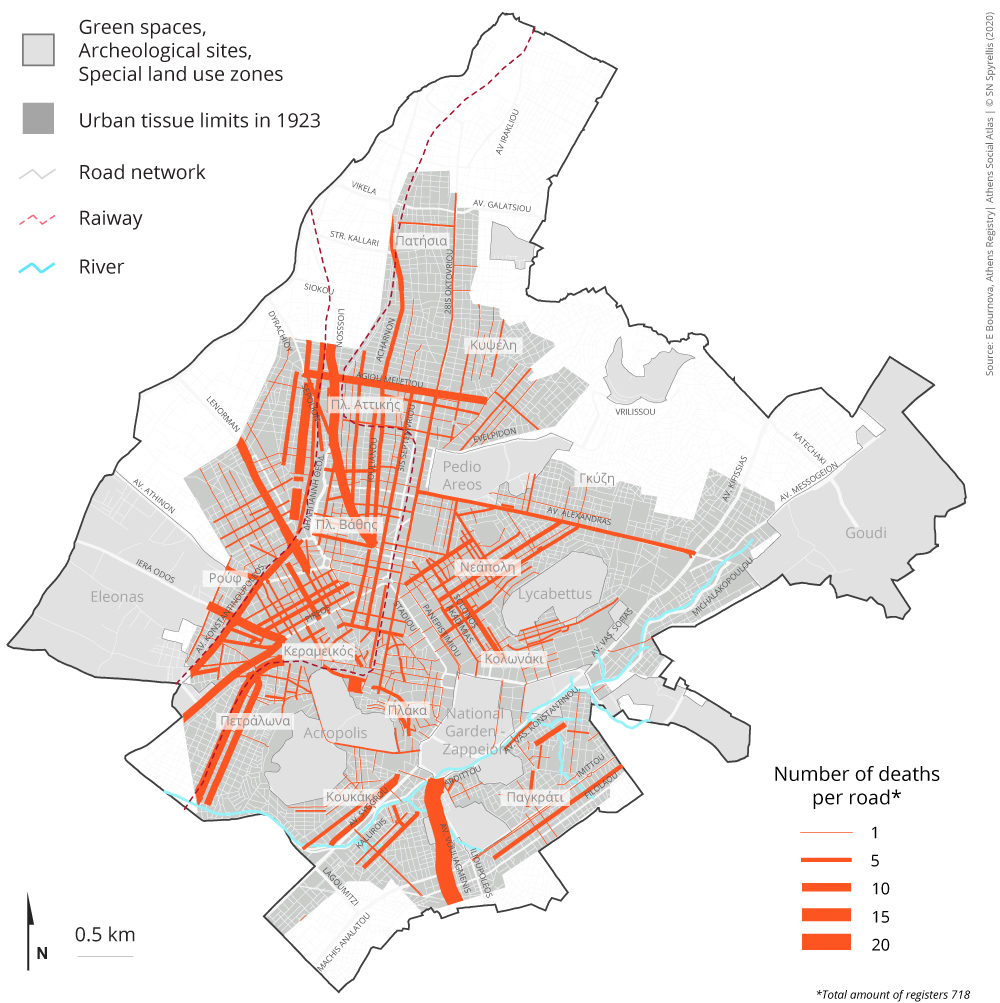

The spatial distribution of victims whose place of death was their place of residence highlights the spread of the influenza across the entire capital (Map 2). The density in the western parishes is to be expected due to the higher population density in these areas, particularly along the railroad line. The same applies to the crowded working class neighbourhoods around the Acropolis (Petralona, Kerameikos) [4]. However, dozens of victims (housewives, schoolgirls, and in working class occupations) were recorded in less densely populated areas such as Profitis Ilias in Pagrati and the adjacent neighbourhood of Gouva. The virus did not even spare the affluent district of Kolonaki, where many housewives and several men whose professions suggest they belonged to the middle or upper classes died in the parish of Agios Dionisios. Even though we do not have precise home addresses for all of the victims, we attempted a detailed mapping (Map 3). This confirmed the virus’s rapid spread through the entire city and particularly along major thoroughfares in the western districts, almost as if it too travelled by railroad from Piraeus to Omonia or took the steam train to Kifissia. Its impact was also detrimental along Vouliagmenis Street where it caused the death of many young children and housewives.

Map 3: Distribution of deaths according to place of death (road)

Source: Municipality of Athens death certificates

Conclusion

The Spanish Flu reached Greece in the summer of 1918 and caused a number of fatalities in Athens from October on, during the second wave of the pandemic. By December its intensity was already dwindling, and as such it did not cause alarm to the country’s public health authorities. Greece, along with other countries including neighbouring Bulgaria, did not experience a resurgence of the disease in early 1919. The influenza’s victims in the Greek capital, in addition to children under five years of age, were mostly males aged 15 or older, especially males aged 25-40 who were soldiers or officers or members of the working class. Most victims came from the capital’s densely populated working class neighbourhoods, but no neighbourhoods were spared by the virus.

The number of influenza victims in Greece was small compared to other countries. After all, in 1918, the Greek state and particularly the Allies were concerned about the 55,000 soldiers stationed in northern Greece who had contracted malaria. The infection had reached such proportions that the commander of the allied forces in the region wrote to his superiors that the Allied Army of the Orient was in real danger of being decimated by the malaria outbreak. The Spanish Flu, then, was but a brief episode in the country’s public health history.

[1] I would like to thank historian Myrto Dimitropoulou for organising and processing the data in order to make possible the spatial depictions presented here.

[2] Je remercie l’historienne Myrto Dimitropoulou pour l’organisation et la gestion des données afin qu’il soit possible de construire les cartes de cette édition.

[3] It is known as Spanish because while countries involved in World War I forbade reporting on the epidemic for fear of hurting troop morale, the press in neutral Spain was able to report on it freely. As a result, people across the world were hearing that Spain was hit by an influenza epidemic while in reality millions of soldiers, but also civilians, were dying everywhere.

[4] See Bournova, E. and Dimitropoulou, M. (2015) The capital’s social and professional stratification, 1860-1940, in Maloutas, T. and Spyrellis, S. (eds), Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material (https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/social-stratification-1860-1940/)

Entry citation

Bournova, E. (2020) The Spanish Flu in Athens, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/the-spanish-flu-in-athens/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.98

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Quand Athènes a du se confronter à la grippe espagnole, στο Isabelle Seguy, Monica Ginnaio, Luc Buchet (sous la direction de), Les conditions sanitaires des populations du passe, Editions APDCA-Antibes-2018, p.p. 237-255.

- Valaoras V (1959) Demographical history of modern Greece (1860-1965), Review of economical and political sciences, 1-2, p. 1-31.

- Κοπανάρης Φ (1933) Η δημόσια υγεία εν Ελλάδι, τύποις Χρ. Χρονόπουλου, Αθήνα, p.p. 108.

- Ανδριανάκος Τ (1925) Η μαιευτική και γυναικολογία εν Ελλάδι, τύποις Π. Δ. Σακελλαρίου, Αθήνα, p.p. 179.

- Bournova Ε., Dimitropoulou Μ. (2015) Stratification socioprofessionnelle de la capitale, 1860-1940 in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material (http://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/fr/)