A city under siege: Military urbanism in contemporary Athens

Daliou Sofia|Kandylis George|Sagia Alexandra

Ethnic Groups, Politics

2015 | Dec

In recent years, the metropolitan area of Athens has been viewed as a locus of multiple security threats for its residents, their property, businesses, civic buildings and public spaces. This is not a new source of concern; moral panic waves targeting a range of social groups have existed for several decades. However, the security doctrine depicting Athens as a city under permanent siege, appeared in a more structured manner around 2000, when Greece was preparing for the Olympic Games. As part of these preparations new anti-terrorist laws were passed, potential “terrorist organisations” were identified and dismantled, unwanted individuals were removed from the city centre, surveillance technologies were installed and traffic restriction zones were put in place.

The prevailing discourse of the safe city is founded on a narrative of an overall security crisis in the city. This narrative tends to become the obvious spatial reflection of a “crisis” in Greek society, regardless of the actual statistics of delinquency or criminality. In the rhetoric of politicians, journalists, administration executives and analysts, the restitution of security is treated as some type of war already taking place in the city (Graham 2010), due to the ideological construct of the security crisis. The call from Antonis Samaras “to re-conquer our cities”, a few months before assuming office as PM in 2012,is the best example of that approach. This war individualises and diffuses insecurity and involves spectacular police operations. These are war-like preparations aiming to detect internal and external enemies and subsequently isolate them or deport them.

Spectacular policing

The culmination of police violence against protesters is not necessarily connected to the militancy of the protesters per se. On the contrary, it seems that the overall goal is to enhance the suppression capacity of the security forces, by upgrading their operational capacity. New motorised departments have been established, disproportionately large police units have been used as well as methods like the physical seclusion of protesters, pre-emptive arrests, the use of undercover police, the selective targeting of specific groups of protesters and the evacuation of squatted buildings (photo 1).

Photo 1: Syntagma square, 29/6/2011

Source: www.youtube.com/watch?v=S20_JuaX8gg)

Source: www.youtube.com/watch?v=S20_JuaX8gg)

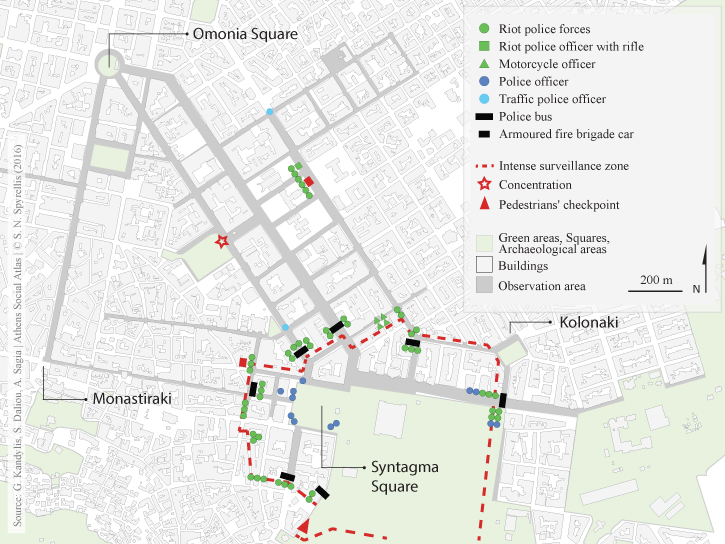

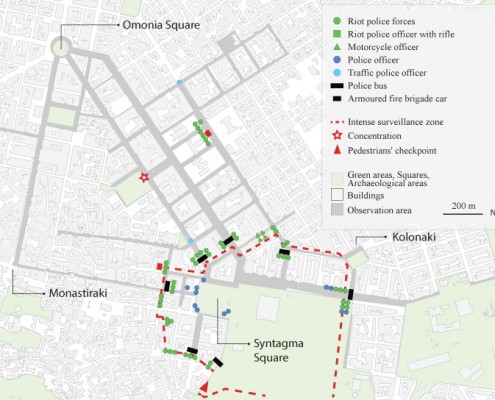

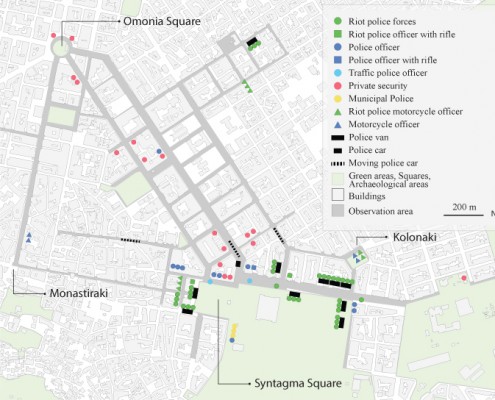

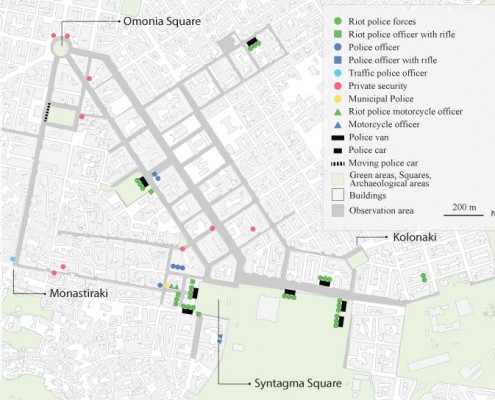

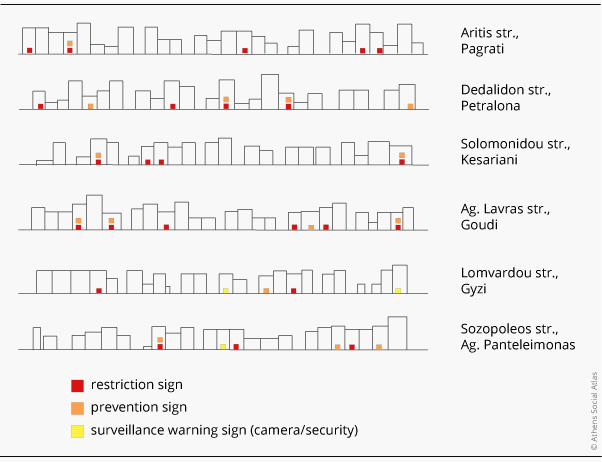

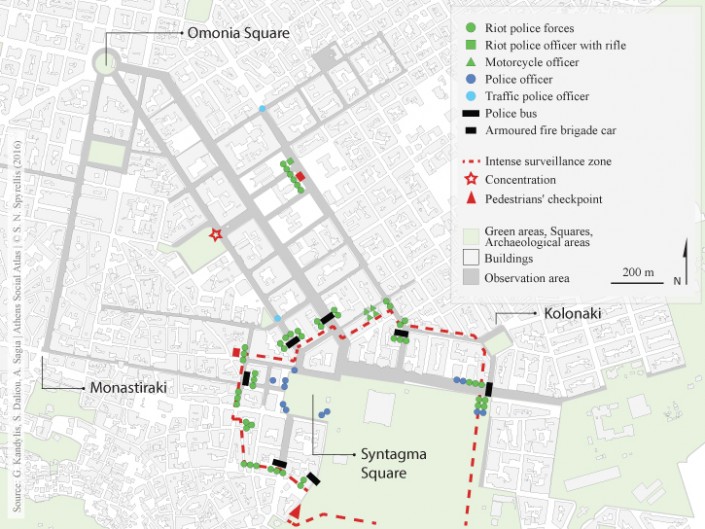

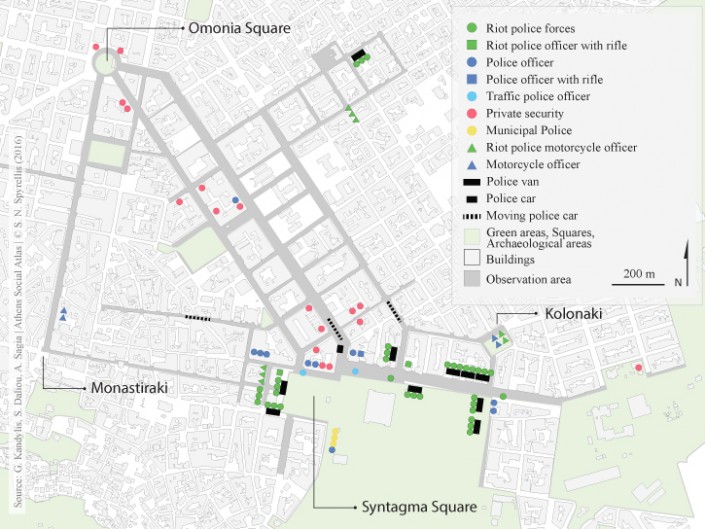

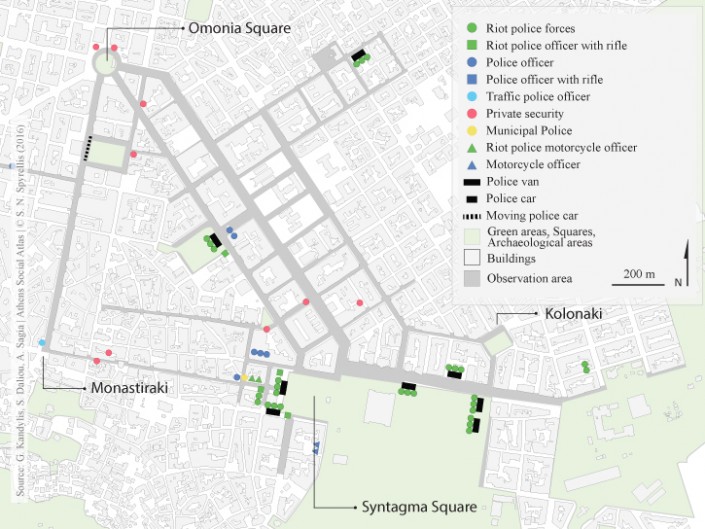

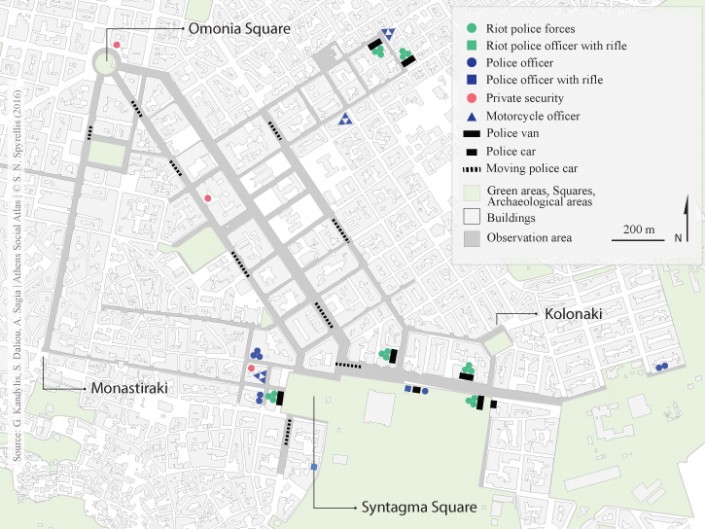

This approach could be termed the ‘spectacular policing’ model because Greek police were systematically promoting the means of violence at their disposal (and sometimes the results of their use), as a deterrent. A minor but indicative case of ‘spectacularisation’ was that of the police blocking off the centre of Athens during the visit of the German Minister of Foreign Affairs in the summer of 2013. The police banned rallies by surrounding the forbidden zone, a big area around the Parliament, using riot police and a large number of vehicles, even in areas where no gatherings were planned (Map 1). In reality, this operation just hindered everyday life in the city centre, since locals and tourists could only pass through a crowd of fully armed policemen (Maps 1-4).

To an extent, this disruption has become a daily routine in the streets of the city centre, ‘spectacular policing’ was regularised and expanded by moving around or stationing riot police and motorbike police units in various points of interest round the clock (Maps 2-4). The spectacle of the permanent presence of policemen equipped with automatic guns, helmets, tear-gas etc. did not deter groups of passers-by in the same way, thus introducing multiple, unexpected inequalities in the ability of different groups to access parts of the city depending on their age, sex, sexual orientation, origins, class, financial situation etc.

The city’s white cells (leukocytes)

In August 2012, Greek police initiated an operation for the mass arrests of migrants in the city centre, under the oxymoron name “Xenios Zeus”. It was the first time that such a raid was given a code name other than the usual “police raid” which were already popular in the ’90s during the deportation of the first Albanian migrants. Later, it became obvious that the new naming strategy was part of an attempt to promote the displacement of migrants as a long-term migration policy, first, within the framework of sensational acts (e.g. lockout of Larissa train station) and then as part of a repetitive routine. Police practices varied from typical non-violent arrests to obliging large groups to stand for long periods of time or to follow military-like orders to move around. The initial TV coverage was followed by daily press releases by Greek Police. The follow-up to “Xenios Zeus” was the “Thiseus” operation which started in the summer of 2014 (photo 2).

Photo 2: “Xenios Zeus” operation, Menandrou str.

Source: www.youtube.com/user/EllinikiAstynomia.

Prior to the May 2012 elections, following hundreds of arrests and obligatory medical tests, the Greek police had arrested and publicly humiliated thirty two seropositive women by publishing their pictures online in order to “protect public health” since “AIDS can be transmitted from an illegal female migrant to the Greek customer, to the Greek family” (comment by the Health Minister, 16/1/2011). Though it did not receive as wide a coverage, the so-called “Thetis” operation (March 2013) resulted in hundreds of drug users being transferred from the city centre of Athens to the Greek police camp in Amygdaleza, where they were obliged to go through a medical examination.

Other than the goal of socially cleansing areas of the city either temporarily or permanently, the common element in those two operations was the medicalisation of security. The police, assisted by public health service personnel (Hellenic Centre for Disease Control & Prevention, National Health Operations Centre) discovered people who were suspected of being infectious and picked out ‘flagitious’ individuals in order to isolate them from the city’s healthy body.

Quarantine: detention centres

Nowhere is isolation applied more systematically than in the case of undocumented migrants, who are not only accused of infectiveness but also of intrusion. The operation of new detention centres in the Athens city limits (Amygdaleza, Acharnes, Corinth) as well as in other areas close to the borders or elsewhere, in April 2012, was promoted as the definitive solution to the problem. The security spectacle has been reversed in the case of the detention camps, which occupied old military premises and comprised small houses in orthogonal arrays lacking basic infrastructure. The exposure of a threat was followed by its disappearance to impermeable areas and spaces. The reports of international organisations and NGOs on the inhumane conditions of detention camps challenged this disappearing act (Cheliotis 2013). However, the detention of an unknown number of migrants in a large number of police stations, indicates that there are detention spaces dispersed in almost every residential area (photo 3).

Photo 3: Amygdaleza detention centre

Source: entefktirio.blogspot.gr

Private economy of security: the added value of fortification

The data available reveal an impressive increase in private security services. The number of low-ranking policemen serving in the wider metropolitan area of Attica has risen significantly between 2001 and 2011 (from 16,400 to approximately 26,000 – data from the “Census Data Panorama 1991-2001” of the National Centre for Social Research and the process of a 10% sample of the 2011 census material). During that period, the total number of employees in private protection services more than doubled (from 5,300 to 12,360 individuals, financial activity sectors L80.1, L80.2). The turnover of security companies, with 2005 as the base year (=100), reached 137.1 in the first trimester of 2014. This index had recorded very high values in the years between 2005 and 2014 and it reflects the exceptional growth of this sector compared to other service sectors.

Security companies offer a grid of individualised services covering the security needs of individuals (i.e bodyguards), residences, shops and offices. That grid expands into the public sphere, not only because private residential areas are patrolled and public buildings are guarded by private guards, but also the responsibilities of private companies have expanded to cover the space outside guarded buildings, transport networks, universities or even entire city areas [1] (photo 4)

Photo 4: Monitoring room of a private security company.

Source: www.facebook.com/Taurushellas

Insecurity and its audience

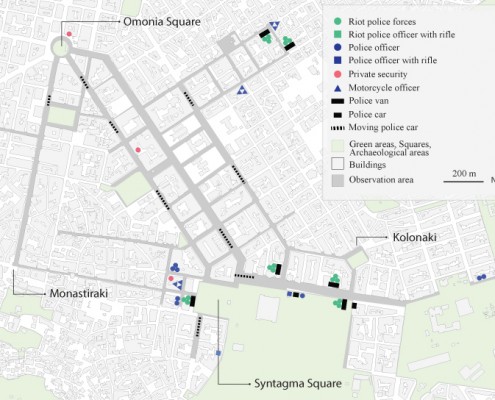

Demand for privatised security is reflected in the propagation of various prevention and restriction signs in the streets of Athens, the entrances of buildings, pilotis, shop windows and front yards. The messages, varying from simple warnings to threats of retaliation combined with fencings, armoured doors, surveillance cameras etc., create the space of daily insecurity and sum up the constantly unsatisfied demand for more protection. This demand expresses the need for private fortification as well as the shrinkage of communal spaces to a sum of defendable doors and corridors. The private agonies identified in this type of population (Εμμανουηλίδης & Κουκουτσάκη 2013) set the ground for the emergence of a type of violence that aims at persecuting (even exterminating) those who have been characterised as flagitious (figure 1).

Figure 1: Security messages on the ground floors of buildings in random streets of Athens.

[1] The website of a security company informs us: “As of the beginning of December, the “Neighbourhood Guard” service has been implemented in the Northern zone of the Municipality of Chalandri and in the Municipality of Glyfada. [Company name], brings a truly unique service to Greece and has created a network of special guards, who perform daily patrols for the safety of people and shops”.

Entry citation

Daliou, S., Kandylis, G., Sagia, A. (2015) A city under siege: Military urbanism in contemporary Athens, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/under-siege/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.45

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Εμμανουηλίδης Μ και Κουκουτσάκη Α (2013) Χρυσή Αυγή και Στρατηγικές Διαχείρισης της Κρίσης. Αθήνα: Futura.

- Cheliotis LK (2013) Behind the veil of philoxenia: The politics of immigration detention in Greece. European Journal of Criminology, Sage Publications 10(6): 725–745.

- Graham S (2010) Cities under siege: The new military urbanism. 1st ed. London, New York: Verso Books.

- Xenakis S and Cheliotis LK (2013) Spaces of contestation: Challenges, actors and expertise in the management of urban security in Greece. European Journal of Criminology, Sage Publications 10(3): 297–313.