Athens: Urban social division during the transition from the city under Ottoman rule to the capital of Greece

Karidis Dimitris

Built Environment, History, Social Structure

2015 | Dec

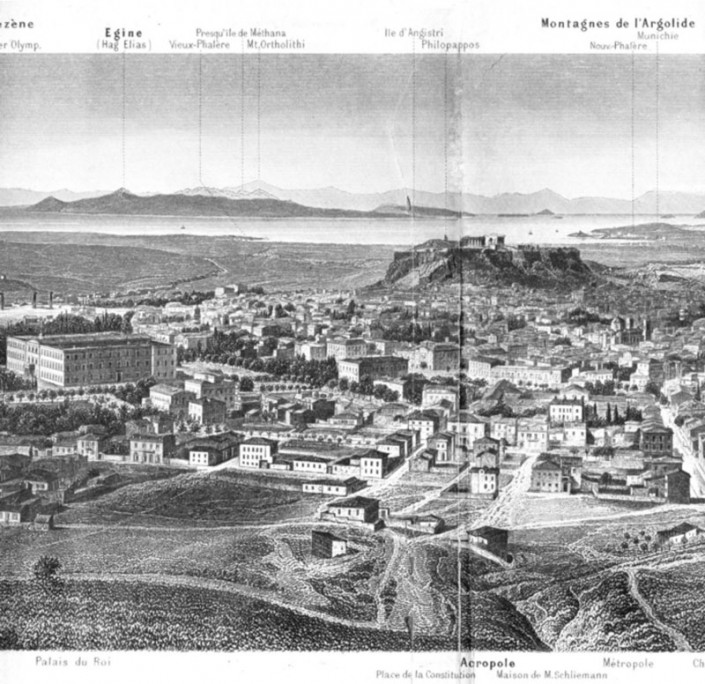

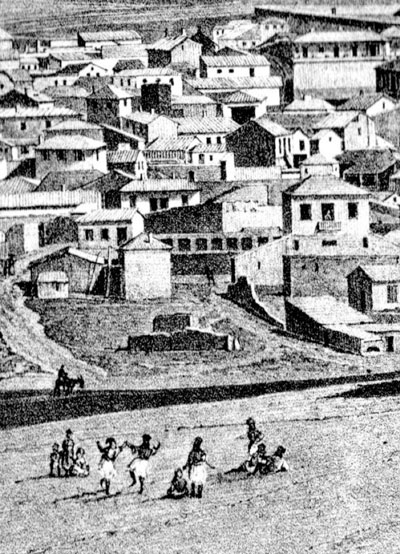

A very brief introductory remark:Under Ottoman rule, Athens presents us with an apparent contradiction. During the first century of the city’s occupation, it reached the peak of its prosperity and urban development. It had a negligible Muslim population (50 households in 1541, compared to about 3,000 Christian households) and there were almost no interventions in its post-Byzantine urban character. On the other hand, by the mid-17th century and still under Ottoman administration, the city had dramatically declined but was also gaining in international reputation thanks to travellers inspired by the European Enlightenment. At that time, the city had acquired oriental features following several centuries of Ottoman interventions. |

The economic, social and political development of Athens during Ottoman rule did not result in a city with strictly differentiated population groups based on ethnic/religious criteria. The boundaries were blurred and there were points of overlap between communities despite the fact that most Muslims were clustered near the market (bazaar), where the few mosques, the madrasa and the hammams were located .However, there is another aspect to be taken into account. In a pre-capitalist society, property values in cities were affected by competition for places of high status. In a society that used space and architecture for the symbolic representation of power, such places were strictly limited to the commercial and administrative centre, -the town market (bazaar) or locations in close proximity to it.

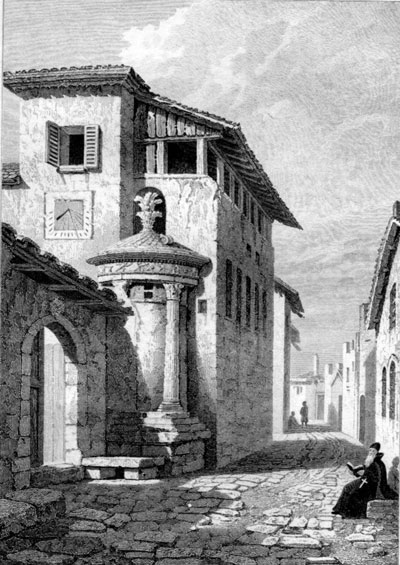

The bazaar was the high status location in the case of Athens too. Those who lived there, in the power centre or around it, were high-ranking Ottoman officials, big landowners (Aghas) or Christian elders. The house of Logothetis, consul of England, was just across the residence of the Voivode, in front of Hadrian’s Library. Western European dignitaries – such as the French consul (and avid looter) Fauvel – also opted to live here. The importance of the bazaar was such that the Monastery of the Capuchin, at the north-eastern part of the city, never really became a competitive centre, although it was the reference point for many foreign visitors throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries.

A clear social landscape emerges in Athens under Ottoman rule: a central area contrasted to the rest of the city, as social groups with political and military power, wealth and prestige behaved in a different way to the majority of the politically subjugated city residents. They experienced tax exploitation and engaged in productive activities. This separation pattern is of additional interest because cities in Ottoman times had a central market that was usually completely separated from the rest of the urban space.In other words, mixed uses (e.g., residences and workshops or retail stores) were avoided in the city centre. However, this functional separation existed only to the extent that the city was an important administrative, economic and military centre . Athens was never such an urban centre under Ottoman rule. For this reason, there was some mix of uses in the central part of the city, albeit limited..

The last point to note relates to a factor, which, if considered along other elements, can explain the patterns of spatial and social distancing. This factor is residential density (along with types of housing, housing parameters, etc.). It has been established that residential densities in Athens during the late Ottoman era were higher in the “Exechoro” compared to densities in the southern part of the city, at the foothills of the Acropolis. The “Exechoro” was the area north of Adrianou Street, or west of the Stoa of Attalos and east of the Capuchin Monastery.

Very quickly after the declaration of Greek independence, the city of Ottoman times became the capital city of a new state, with simultaneous changes in its political, social and economic structure. The need for the rapid transformation of a community into a society required an extremely difficult shift: from belonging to a community, meaning to share common cultural characteristics such as religion, language, customs, etc. – the cornerstones of social solidarity, to being part of a society, which is perceived as an institution, as an “externality”, in which each person is a statistical unit that fits into categories, quantities and changing flows – the constituent parts of a (social) functional relationship.

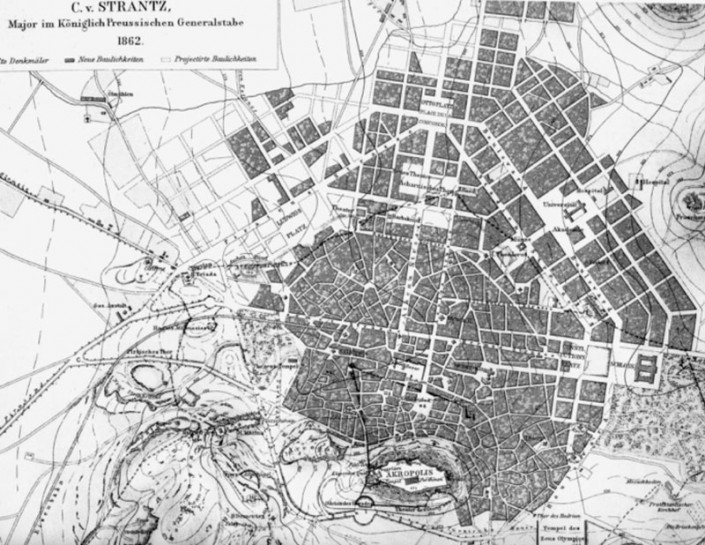

Therefore, it is worth remembering that the new urban plan prepared for the capital (Kleanthis and Schaubert plan, 1834) did not per se have the power to impose specific forms of spatial division and thus any forms of social spatial division observed in the first post liberation decades are not due to it.

Two of the capital’s new main avenues, Athinas Street and Peiraios Street, would bear the brunt of a (new) social spatial division a few decades after the attempts to implement the first urban plan of Athens had started in earnest. Incidentally, the plan had officially been rejected despite its original approval. Although both avenues were included in the original plan, each avenue had its own particular dynamics, arising both from its contribution to the process of reproduction of spatial and social differentiation and from the point in time after which each of them started to integrate forms of separation.. Athinas’ Street undeniable ideological role in the Kleanthis plan, due to the symbolic connection of the seat of power with the prestige of antiquity, often obscures its importance as a host of functional changes. That role prevailed when the planned Palace was shifted elsewhere. Specifically, as the new production setting and the new (social) relations of production took hold, the previous feudal structure started to crumble. The various craft/artisan production uses and the commercialisation/exhibition of the produced goods changed: their earlier presence in a single spatial unit and their connection to the same person were soon replaced by production areas and “linear” spatial elements (commercial axes, product display and exhibition areas), with specialised promoters for each process. This was the role of Athinas Street with respect to the areas behind or near it, such as the Psiri area and the “traditional” bazaar. In fact, it was anticipated that its commercial role would be enhanced by the “hosting” it would provide to shopping centres at its northern end. Athinas Street thus assumed a crucial role, which originally served mainly as a trigger of urban/functional differentiation and not for social segregation purposes.

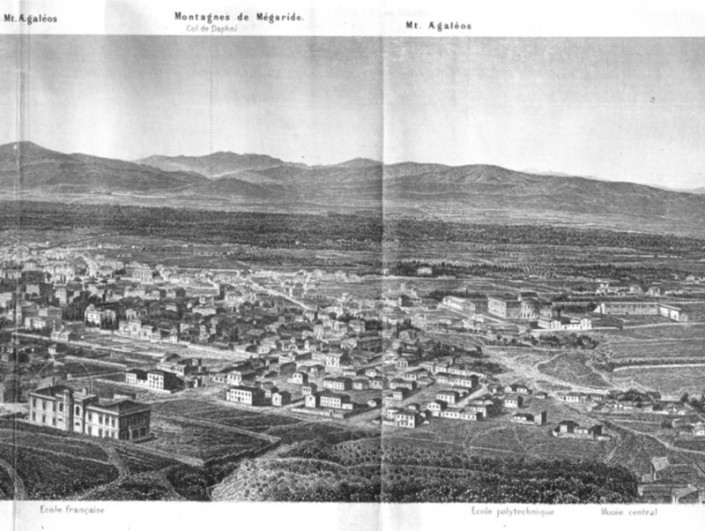

A few years later, Peiraios Street played a synergistic role to that effect. It was originally intended to connect the capital with its (new) port, in the shadow of the “Long Walls”. However, it acquired a new character in the mid-19th century, after the Metaxourgeio was built at a short distance from the street (to its west), close to Omonoia Square. The Metaxourgeio was originally intended to be a shopping centre but eventually became a silk factory. Α few years later, the foundations for the new partitioning of the capital were laid when the 19th century’s inherently revolutionary presence of industrial activity manifested itself in Athens with the gas factory, at the junction of Peiraios and Ermou Streets. Athinas Street now served as a “border”. The western part of the city, the part to the west of Athinas Street, was an industrial zone and a low-income residential area. The first social housing soon emerged around Metaxourgeio and the gas factory. The eastern part of the city, the part east of Athinas Street, was the area for services and middle and upper social class residences.

However, this situation was not static. The border of functional and social segregation is not consolidated in space and time – it exists only for as long as there are reasons for the continuous reproduction of this role. The key planning interventions of the second half of the 19th century are therefore more intelligible if they are viewed from that perspective On the one hand, the new Pireaus-Athens railway terminated at Thissio; the recreation area of the Faliro Bay was integrated into that operation, and industrial activity was promoted in Piraeus and along Peiraios Street itself. On the other hand, the hegemonic role of a newly established urban character was reinforced, either by creating a particular architectural style or with inner avenues, such as Alexandras avenue, defining individual areas. Both of these practices were echoing similar attitudes to architectural and urban design in 19th century Europe. These observations are repeated further if one looks at two residential areas which were incorporated into the city plan during the last decade of the 19th century: the indifferent, Hippodamian plan for Kolonos to the working class west, and the elaborate, almost Renaissance style, plan for Vathrakonissi (Pagkrati) to the east.

Entry citation

Karidis, D. (2015) Athens: Urban social division during the transition from the city under Ottoman rule to the capital of Greece, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/urban-social-division/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.6

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Καραδήμου Γερόλυμπου Α (1997) Μεταξύ Ανατολής και Δύσης. Θεσσαλονίκη και βορειοελλαδικές πόλεις στο τέλος του 19ου αιώνα. Αθήνα: Τροχαλία.

- Bastea E (1994) Athens. Etching images on the street: planning and national aspirations. In: Çelik Z, Favro D, and Ingersol Lr (eds), Streets: critical perspectives on public space, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 111–124. Available from: http://www.unm.edu/~ebastea/pdfs/Streets.pdf.

- Bierman IA, Abou-El-Haj RA and Preziosi D (1991) The Ottoman city and its parts: urban structure and social order. Bierman IA (ed.), New Rochelle, New York: Aristide d Caratzas.

- Karidis D (2014) Athens, from 1456 to 1920, the Town under Ottoman rule and the 19th century Capital City. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Vidler A (2011) The scenes of the street and other essays. New York: The Monacelli Press.