Recording the use and ownership patterns of apartments in the Athenian apartment block (polykatoikia)

Koutoumanou Anastasia

Built Environment, Housing, Social Structure

2018 | Dec

Athens is at the top of the list of Greek cities in terms of the presence of the dominant building type of the polykatoikia (apartment block). Its central municipalities saw intensive construction of the polykatoikia model in the first three post-war decades of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s as well as the land-for-flats barter mechanism (antiparochi). Today, 40 years after this period of intensive construction, the image of the city has hardly changed. This entry highlights the fact that these post-war polykatoikies—despite the depreciation they have experienced since the 1980s and 1990s due to the quality degradation of housing conditions in the central areas and the outflow of residents to the then sparsely populated suburbs (Μαλούτας, 2000)—are in permanent use as they constantly get new residents coming from diverse social groups.

Recording the use and ownership patterns of apartments in the Athenian apartment block (polykatoikia)

The polykatoikies that were built in the first three post-war decades of the 50s-70s in Athens [1] remain the same in number but aged and, mainly, depreciated.

The depreciation of this dominant building type of Athens raises questions. What will be the end of the natural life of these buildings? Is there or will there be gradual abandonment of polykatoikies? Can changes in the ownership status of polykatoikies reverse the downturn? (Μαντουβάλου, Μπαλλά, 2004)

In recent years there has been a shift of interest regarding the future of the Athenian polykatoikia, especially in academia. Gradually, this building type is moving from the margins towards the center of research interest.

This entry tries to understand the intentions of the current users [2] of the polykatoikia and to what extent they reflect (or not) its gradual abandonment. It records snapshots of inhabitance and ownership whilst attempting to answer the following question: has the Athenian post-war polykatoikia been continuously inhabited despite the gradual move of a significant number of residents away from the center of Athens that was observed in the 1980s and 1990s?

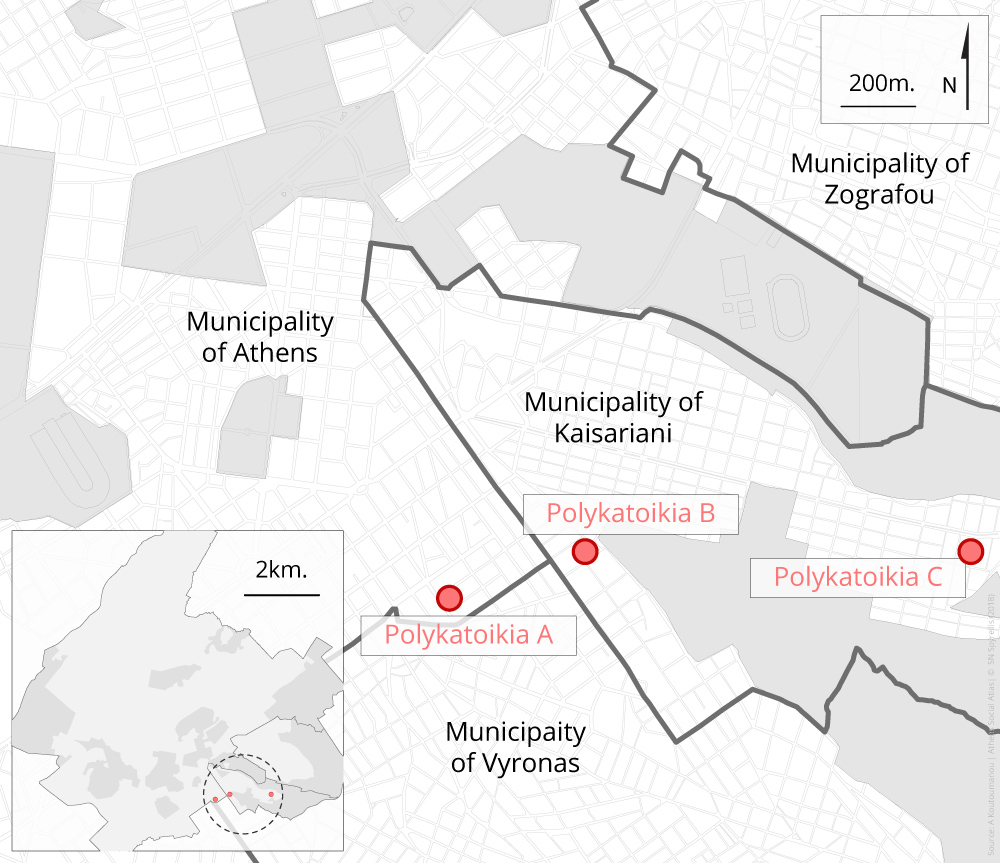

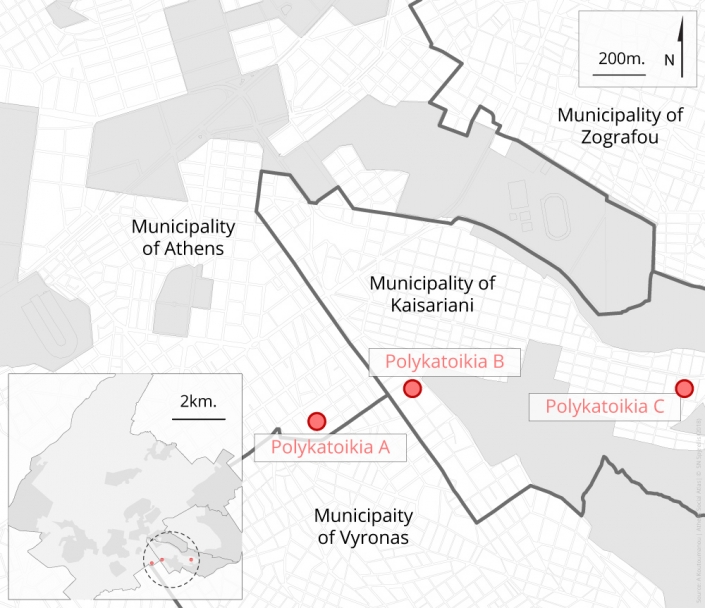

Map 1: Location of the 3 apartment blocks (polykatoikies)

The answers to this question given here are the result of a small-scale research project [3] in three polykatoikies in the neighbourhoods of Pagrati and Kaisariani and are based on interviews with apartment residents [4]. The three polykatoikies are typical examples of this type of building, produced by a builder-contractor through the flats-for-land system (antiparochi). They differ in size due to the different size and shape of of the plots of land they were built on (Figure 1).

Brief presentation of the 3 apartment blocks polykatoikies

Figure 1: Urban block plot and the 3 apartment blocks polykatoikies

Polykatoikia A: Pagrati | elevated ground floor, 3 normal floors, 2 top floors, 1 roof top cabin | 10 apartments | 9 interviews | completion of construction 1972

Polykatoikia B: Kaisariani | elevated ground floor, 3 normal floors, 2 top floors, roof | 24 apartments | 17 interviews | completion of construction 1973

Polykatoikia C: Kaisariani | elevated ground floor, 4 floors, 1 roof top cabin | 20 apartments | 5 interviews | completion of construction 1974

Categories of users and ways of habitation

Although the size of the apartments varies, the density is very low, with only one four-person household reported and only one two-room apartment with more than two residents (Figure 2). Extreme cases are considered to be the 2 five-room apartments and the 6 four-bedroom apartments with just one or two residents.

Figure 2: Apartment size and number of residents

Homeownership outweighs rentals in a ratio of 20/11. An interesting characteristic emerges in polykatoikia B where 70% of homeownerships have not changed since 1972 (Figure 3). If the apartments owned by the initial landowners —either empty or rented—are also considered, then at least 14 out of 24 apartments have the same owner since 1972. In polykatoikia B, it is also remarkable to notice the concentration of tenants on lower floor apartments, while all residents on higher floor apartments, 3rd or higher, are owner-occupiers.

Figure 3: Homeownership and rent

Regarding the age groups in the three polykatoikies, those over 50 years old and those between 20 and 50 are found in equal numbers (20/18), while children and those under 20 years old are rather scarce—in 4 of the 38 apartments (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Age groups of residents

While the apartments are predominantly used as main residence, a small number of cases, 8 of the 40 apartments (Figure 5), are secondary residences. The age of the residents provide an first explanation. People over 50 occupy 7 out of the 8 secondary residences. 5 of them have been continuously using the apartment since it was built. These features imply the presence of households who bought these apartments in the 1970s as young families. In the meantime the children have grown up and moved out, while the parents remained only partially in these residences. In 4 out of 8 large apartments, this assumption is verified, and also explains the low densities observed in Figure 1. Today, the elderly parents share their presence among their own apartment and an owner-occupied house in the periphery of the Attica region, or their child’s family house, where they usually assist by taking care of their grandchildren.

Figure 5: Main and secondary residence

In terms of marital status, the single residents aged between 20 and 50 constitute the majority (Figure 6). Moreover, there is an equal percentage of the following 3 categories of households: couples with children, couples with children living elsewhere and couples without children.

Among the childless couples, only one is young enough to move potentially to the category of couples with children. Couples with children living elsewhere are couples whose children have grown up in the couple’s apartment, which they will eventually inherit—the case for all 6 couples mentioned earlier. Despite the almost equal presence of the 20-50 and over 50 age groups, the second tends to widen. In 2 households, the adult children still live with their parents, but in the near future, according to the interviews, they will move to a new house with their own family. This will further increase the rate of the over 50 age group. This could be taken as an indication of the gradual ageing of the residents’ population.

Figure 6: Marital status and age groups

In the homeownership and rent diagram related to age groups (Figure 7), the ratio for those over 50 years is 16/3, while for those between 20 and 50 years it is 8/8. It can be assumed that the over 50 years old have managed to own apartments through their work activity or their inherited assets, while the next age group is much more equally divided between homeownership and rent.

Figure 7: Homeownership – rent and age groups

Within a total of 11 apartments, the most populous group of single 20 to 50 years olds is distributed in the ratio of 3/3/5 to homeownership / hosting / rent. Considering hosting as a form of homeownership (since in all our cases the hosted are children of those who own the apartments they live in), the effective ratio for homeownership / rent is 6/5, i.e. almost equal.

In terms of the ways of access to homeownership—regarding the owner-occupiers and the hosts—a distinct category of family planning emerges. This refers to young people who become homeowners through heritage (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Access to homeownership and age groups

If homeownership through the land-for-flat system concerns almost exclusively the current residents over 50 years old, homeownership for the 20 to 50 years old group derives either from inheritance from parents or grandparents or takes the form of occupancy that will eventually become homeownership—hosting or cohabitation with the parents who are currently the legal owners.

This makes the intentions of the particular age group important as they will become the owners and therefore will manage these apartments in the future; continuing to occupy the apartment or making it available for rent or even selling it, will be their own decision. This age group will affect the ownership map of polykatoikies in the coming years. It turns out that today, young people do not invest in city center apartments, but will not decline homeownership if the latter does not require a monetary capital. This probably reflects the well-known predilection of Greek households for homeownership compared to rented accommodation (Κουβέλη, Σακελλαρόπουλος, 1984).

In the usual process of life, younger generations often inherit owner-occupied houses from their deceased parents and grandparents or benefit from other forms of integenerational transfers of properties while their progenitors are still alive. This inflow of younger people into the polykatoikia tends to compensate for the ageing population that was discussed above (Figure 6). Adult children move out of their parental homes to live elsewhere with their own families, whilst other young people move in the polykatoikia to live in the apartments they inherited. These are counterbalancing relocations that seem to maintain the age balance in the post-war Athenian polykatoikia.

Continuous owner-occupancy since the 1970s

Figure 9 presents two periods for polykatoikia B, the first in the 1970s and 1980s and the second from 2010 to date. It illustrates the gradual ageing of the residents as well as the age renewal. Only households with continuous owner-occupancy to date are taken into account.

Figure 9: Residents’ aging

Figure 9 also shows the size of the apartments in polykatoikia B in order to understand the density of habitation in each one. There are significant differences between the two periods considered. During the first period (1970s and 1980s), the apartments are inhabited by nuclear families with one to three young children or by elderly couples. Since 2010, most of the apartments are inhabited by one or the couple of the elderly parents and are often used as secondary accommodation. Among those who grew up in this polykatoikia and are now part of the 20 to 50 years old age group, only two still live in this polykatoikia. At the same time, there is a renewal of the population resulting from the relocation of the grandchildren of the first residents, who chose to live in the apartment they inherited.

Use of the apartments

Figure 10 illustrates the trajectory of each apartment from the day it was constructed to date. More specifically, information is displayed concerning how it was acquired by the first owner, how he/she used it, if he/she lived in it, rent it, offered its use for free to a relative or sold it. By carefully examining the figure, it appears that the apartments were left empty only for very short periods of time. When they were not being used by the owner or hosted some relative, they were mostly rented.

Rented occupancies alternate throughout the whole examined period in contrast to sales.

Figure 10: Use of the apartments

Specifically, most sales took place in the first decade (1970s) and especially during the year the construction was completed. No sales were reported after 2008, while in the 1980s and 1990s there some scarce sales occured. The acquisition of an apartment through inheritance is also registered, with the new owner often residing in the inherited apartment. This is particularly witnessed after 2000 and especially since 2010, which may be related to the financial crisis. More specifically, all 4 cases of households that inherited an apartment (Figure 8), chose to leave their previous (rented) residence and to live in their own house—even if the latter was not more convenient—due to financial difficulty. Owner-occupancy may result in a neighborhood change or in lowering the quality of living conditions in the owner-occupied, but old apartment. Inspite the negative characteristics of inherited houses, the avoidance of having to pay rent seems overwhelming for some residents.

The apartments that were constantly on the rental market throughout the examined period form a particular category. These apartments were bought for investment, i.e. their purchase was not meant to cover a housing need, but to provide income (through renting) for the investor. This investment was often made by the main actors of the land-for-flats system (land-owner or builder-contractor) who chose not to sell some of the apartments produced by their joint venture and beyond what was intended to cover their own housing needs. The owners of these apartments very often lived elsewhere in Greece and chose to invest in this way in the capital. Depending on circumstances, such apartments host family members for short or longer stays, or become student accommodation for the investor’s children pursuing studies in Athens. These are multifunctional apartments adapting to the needs of their owner’s families at different periods of their life cycles. They are usually the small apartments in lower floors that enabled the partition of apartments between the land-owner and the builder-contractor as well as both parties’ investment strategies.

Eventually, the apartments in the polykatoikies of Athens—whether small or large, owner-occupied or rented—always end up used according to the changes in the family planning of their owners. The family being traditionally an active social cell involving different generations and several members, there is a trend of permanent use of these apartments, going against the tendency to desert and abandon them that may have been recorded in the past (Εμμανουήλ, 2007). Such a negative impression may be given by the ageing image (façade) of the Athenian polykatoikies due to inadequate maintenance and hence their material deterioration. However, despite their material deterioration, these neglected buildings remain ‘alive’ and vibrant cells of the city.

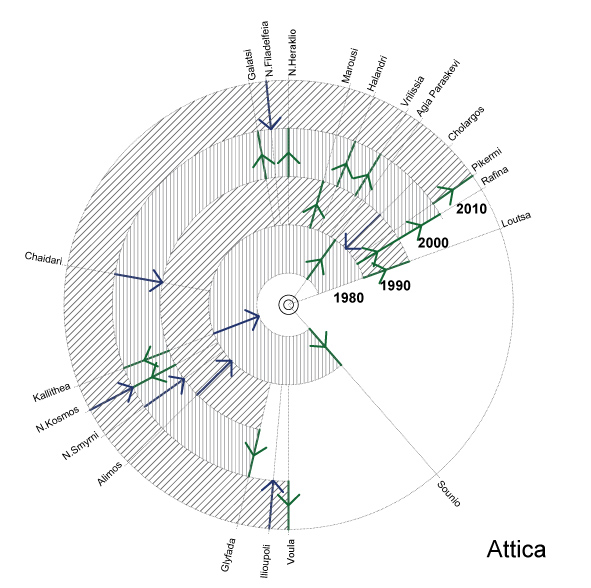

Relocation of residents

Figure 11 depicts the relocations to and from the three polykatoikies between the 1980s and 2010s. The inflow / outflow ratio to and from the three apartment buildings in Kaisariani and Pagrati is as follows: 1/2 in the 1980, 2/3 in the 1990s, 2/8 in the 2000 and 3/2 in the 2010s. In the 1980s, the first relocation is recorded to a vacation home in Sounio, a privileged coastal area at the southern tip of Attica. The second outflow involves a family who sold their apartment to buy a similar property in the suburb of Agia Paraskevi. These episodes illustrate the beginning of the decline of the polykatoikia and the central neighbourhoods in the Municipality of Athens and those around it, like Kaisariani. In the 1990s, the outflows involved relocations to former vacation homes in eastern Attica (Rafina and Loutsa) by middle-aged residents, as in the case of the outflow to Sounio. The 2000s comprise the largest number of movements, especially outflows; all involve young couples that got married and chose a new place of residence. Glyfada, Heraklion, Vrilissia, Chalandri, Pikermi, Neos Kosmos and Galatsi—close suburbs in most cases. This decade is also interesting regarding the inflows. Inflows are not due to dissatisfaction with the previous area of residence or housing unit, but to the desire to move to a privately owned apartment. The financial difficulties expereienced during the crisis in this decade, when these inflows to the study areas are more frequent, explains in some cases the move and use apartments in these polykatoikies as owner-occupants. The owners chose to move in these apartments—even if they have previously been vacant or rented, which indicates that they previously opted for a more convenient housing option—to improve their financial situation. These moves indicate the potential sacrifice of a better neighbourhood, but have the advantage of moving closer to the centre. In the 2010s and amidst the financial crisis, inflows outweigh the outflows for the first time for the three apartment blocks. During this and the revious decade, the outflows to southern or eastern Attica—i.e. to distant suburbs—are not moves to vacation areas, but to places of permanent residence.

Figure 11: Relocations of residents in Attica

Residential mobility, even though rather limited, is constant throughout the whole period under review, with ups and downs. The main reasons for moving out, during the first decades, are the choice to relocate to the suburbs—even to vacation areas—often related to the formation of a new household by young adults, while in the last decade the main reason for moving in is the opportunity to use some existing housing property—often inherited—to alleviate financial difficulties.

Conclusions

This brief investigation outlined the main profiles of residents in the typical Athenian polykatoikia that could be identified in the three apartment blocks under scrutiny.

The first occupants, elderly now, who remained in these apartment blocks while their children moved, when they formed their own families, to other, usually more expensive, areas. Some of these first occupants, also elderly, are now living at these polykatoikies intermittently since they also live elsewhere (usually away from the centre) in a vacation home, but visit the centre and keep the apartment as a secondary residence. Young people, who, under the pressure of the financial crisis, left the previous houses they were renting to came and live in the apartment they inherited to reduce housing expenses.

The apartments of the post-war polykatoikia, although aged and poorly maintained, did not cease to play a decisive role in the planning of Greek families during their long presence. Although less densely populated and with a significant lack of young families with children, the apartments continue to be inhabited and adapt to new housing and economic circumstances. Throughout their trajectory, their owners used them in a way that either covered housing needs or provided extra household income. Their occupants are constantly moving in and out, following different motives according to their age and other characteristics.

Eventualy, the Athenian polykatoikia is not abandoned, but mostly undergoes constant changes that keep it alive. Moreover, its ageing population gets younger through the recent inflows of young inhabitants.

This constant mobility of residents to and from the polykatoikia complements its image, which is certainly not a picture of abandonment but of change. The post-war apartment block is present in the city’s life even if this presence is overlooked. Investigating the role of this type of building is of great importance and should be considered essential for the debate regarding the future of Athens.

[1] Concerning the intensive post-war building construction in Athens βλ. (Burgel, 1976), (Μαντουβάλου, 1988), (Μαρμαράς, 1991), (Μπίρης, 1966)

[2] Users are the tenants, the owner-occupiers and the guests. ‘Hosting’ means the concession by the owner of an apartment for habitation to a third person, while the owner lives somewhere else.

[3] This entry is based on the author’s diploma thesis (2006), in the postgraduate program ‘Architecture-Spatial Design’, ‘Urban and Regional Planning’ supervised by Maria Marcou and Dimitris Isaias.

[4] Significant contribution to this research was provided by the following publications: (Καμούτση, Μαλούτας, 1986), (Κουβέλη, 1986), (Κουβέλη, Σακελλαρόπουλος, 1984)

Entry citation

Koutoumanou, A. (2018) Recording the use and ownership patterns of apartments in the Athenian apartment block (polykatoikia), in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/use-and-ownership-patterns-of-apartments-in-the-athenian-apartment-block/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.84

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Burgel G (1976) Αθήνα. Η Ανάπτυξη μιας Μεσογειακής Μητρόπολης. Αθήνα: Εξάντας.

- Εμμανουήλ Δ (2007) Κοινωνική διαίρεση του χώρου και ταξικός διαχωρισμός στην Αθήνα: Ο ρόλος της οικονομικής τάξης, του status και της κατοικίας. Στο: Συμπερασματικές παρατηρήσεις: Θεωρητικές συνέπειες και σημασία του στεγαστικού-οικιστικού μοντέλου, Αθήνα: Ινστιτούτο αστικής και αγροτικής κοινωνιολογίας.

- Καμούτση Π και Μαλούτας Θ (1986) Προέρευνα για τις στεγαστικές συνθήκες. Συνεντεύξεις με νοικοκυριά στην περιοχή της Αθήνας. Αθήνα: ΕΚΚΕ.

- Κουβέλη Α (1986) Προβλήματα εμπειρικής προσέγγισης των στεγαστικών συνθηκών. Το ερωτηματολόγιο της έρευνας. Αθήνα: ΕΚΚΕ.

- Κουβέλη Α και Σακελλαρόπουλος Κ (1984) ‘Στεγαστικές συνθήκες στην Ελλάδα. Σχεδιασμός της έρευνας. Αθήνα: ΕΚΚΕ.

- Μαλούτας Θ (2009) Κοινωνική κινητικότητα και στεγαστικός διαχωρισμός στην Αθήνα: Μορφές διαχωρισμού σε συνθήκες περιορισμένης στεγαστικής κινητικότητας. Στο: Μαλούτας Θ, Εμμανουήλ Δ, Ζακοπούλου Έ, κ.ά. (επιμ.), Κοινωνικοί μετασχηματισμοί και ανισότητες στην Αθήνα του 21ου αιώνα, Αθήνα: ΕΚΚΕ, Μελέτες – Έρευνες ΕΚΚΕ, σσ 28–61. Available from: http://www.ekke.gr/open_books/athens_2008.pdf.

- Μαντουβάλου Μ (1988) Ο Πολεοδομικός Σχεδιασμός της Αθήνας (1830-1940). Στο: Σακελλαρόπουλος Χ (επιμ.), Από την Ακρόπολη της Αθήνας στο λιμάνι του Πειραιά. Σχέδια Ανάπλασης Αστικών Περιοχών, Αθήνα: Εθνικό Μετσόβιο Πολυτεχνείο – Politechnico di Milano.

- Μαντουβάλου Μ και Μπαλλά Ε (2004) Μεταλλαγές στο σύστημα γης και οικοδομής και διακυβεύματα του σχεδιασμού στην Ελλάδα σήμερα. Στο: Οικονόμου Δ, Σαρηγιάννης Γ, και Σερράος Κ (επιμ.), Πόλη και Χώρος από τον 20ο στον 21ο αιώνα, Αθήνα: Σχολή Αρχιτεκτόνων Μηχανικών ΕΜΠ, σσ 331–344.

- Μαρμαράς Ε (1991) Η αστική πολυκατοικία της μεσοπολεμικής Αθήνας: Η αρχή της εντατικής εκμετάλλευσης του αστικού εδάφους. Αθήνα: Πολιτιστικό Ίδρυμα Ομίλου Πειραιώς.

- Μπίρης Κ (1966) Aι Αθήναι από του 19ου εις τον 20ον αιώνα. Αθήνα: Έκδοσις του Καθιδρύματος Πολεοδομίας και Ιστορίας των Αθηνών.

- Συλλογικό Έργο (2002) Κοινωνικός και Οικονομικός Άτλας της Ελλάδας. Οι πόλεις. Μαλούτας Θ (επιμ.), Αθήνα, Βόλος: Εθνικό Κέντρο Κοινωνικών Ερευνών, Gutenberg, Γιώργος & Κώστας Δαρδανός, Πανεπιστημιακές Εκδόσεις Θεσσαλίας.