2016 | Sep

Vacant houses are a recurrent object of public debate, sometimes as an indication of wealth for the large percentage of Greek households who possess more than one dwelling, and sometimes as a social resource which could contribute to resolving acute housing problems, but remains untapped.

One of the reasons creating the impression that poorer German households are coerced to assist wealthier households in the European South, is the much higher rate of homeownership in southern countries and especially in Spain and Greece, where this rate is over 80%. This impression was created by the eclectic reading of the data provided by a research project of the European Central Bank (ECB, 2013a and 2013b) and was presented in that way by major newspapers (Financial Times, 2013). The eclectic reading consisted in choosing to compare median rather than average household wealth in Germany and in countries of the European South. What is compared, therefore, is the size of the median fortune –i.e. of the fortune occupying, for example, the 50th position in a hierarchy of 100 fortunes according to size– rather than the average size of fortunes in each country. This eclectic reading dissimulates the much grater inequality of wealth distribution in Germany (approximately four times higher than in the countries of the South) and enables the deceptive claim that a country with poor households has to bear the weight of other countries’ sins in the Eurozone.

The claims have already been answered adequately (De Grauwe and Ji, 2013). In this text, the focus is on the real content of the term “vacant houses” in Athens. Before this, we should remind that homeownership in the countries of the European South has a relatively different social function than in the North, since it also concerns large parts of the lower income strata due to the fact that social housing systems have been historically much less developed than in the countries of Northern or Western Europe.

The first question is whether these vacant houses in Athens are a sign of wealth and well-being, in the sense that a significant part of the housing stock appears to be used only occasionally. Vacant houses exist in large numbers in other cities as well –for example in London– where they are also not used on a regular basis by their owners who are often part of a global elite investing in the property market of a first class global city. The second question is whether the vacant houses are owned by Greek households and the third –and probably the most important– is whether this stock can be used to address housing problems that have multiplied during the prolonged crisis. We will try to approach these questions through the location patterns of vacant houses, using the detailed data provided by the censuses of the Greek Statistical Authority (ELSTAT).

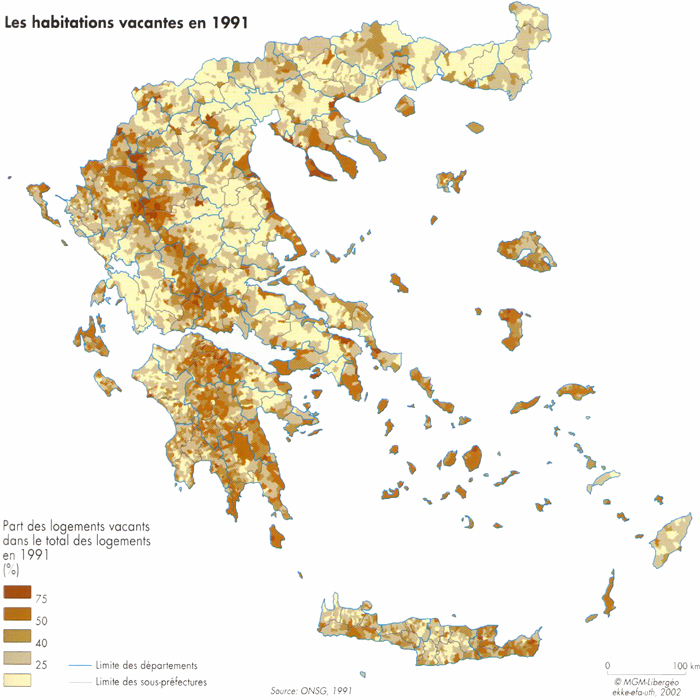

The map of vacant houses in Greece for 1991 (Maloutas, 2003: 71) reveals three different types of concentration (map 1), which correspond more or less to different types of vacant houses. The most extended concentration comprises agglomerations in mountainous regions, mainly villages on the Pindos mountain range and its extension to Peloponnesus. These vacant houses are mostly abandoned by their owners and, in case they are operationally adequate, they are occasionally used as a convenient, low-cost leisure home. All these houses in depleted mountainous villages –whether occasionally used or not– have been registered as vacant by the census since it was carried out in March 1991. This concentration pattern is linked to the rapid urbanization in the post-war, which led to the gradual abandonment of the most remote areas and the relocation of their population to small and mainly large agglomerations. Therefore, it is not surprising that the map of vacant houses is quite similar to the country’s geomorphological map, with the communities on mountainous areas presenting the highest percentage of vacant houses.

Map1: Percentage of vacant houses by local community in Greece (1991)

Source: Maloutas (2003)

The second type of spatial concentration was related to vacant houses in tourist regions, mostly in the popular islands of both the Aegean and the Ionian sea. However, this type is not unrelated to the first one, since higher vacancies are mainly observed in the less developed areas of these islands, as we can observe in Crete, Rhodes or Lesvos. A large part of these vacant properties probably belongs to foreign owners.

The third type of vacancies’ concentration concerned also leisure houses, which we can presume however to have a more regular use (weekend homes) since they are quite close to large cities. This type is also related to post-war urbanization and its impact on their periphery, mainly on coastal areas. These concentrations are mainly observed in the coastal regions of Attiki around Athens and in the neighboring prefectures of Viotia, Korinthia and Evia, as well as around Thessaloniki in the coasts of Chalkidiki and Pieria. In the early 1990s Athenian households possessed leisure houses at a rate between 15% and 20%. Most of these were located quite near the city (Maloutas, 1990). The ownership of leisure houses was socially diffused following the way these houses were acquired, i.e. through the process –often illegal– of self-promotion of small individual units at the city’s periphery, used previously for acquiring their main residence.

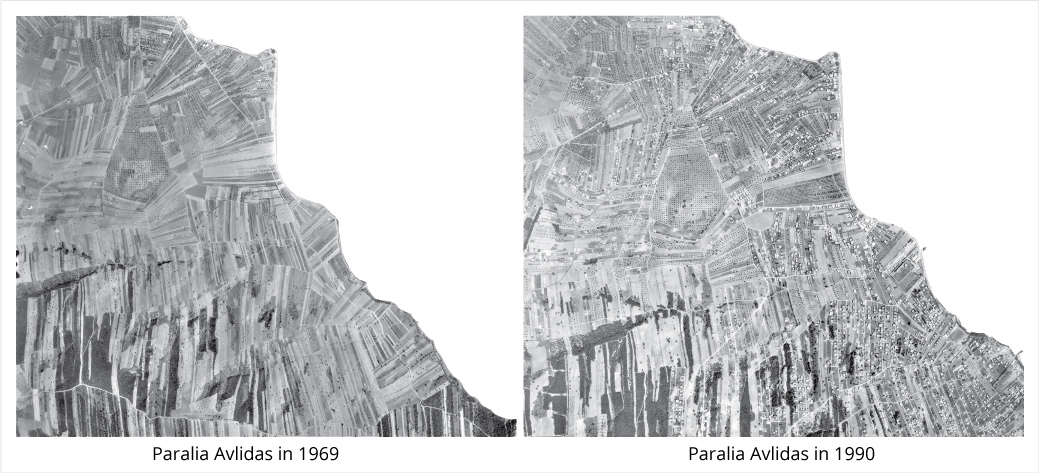

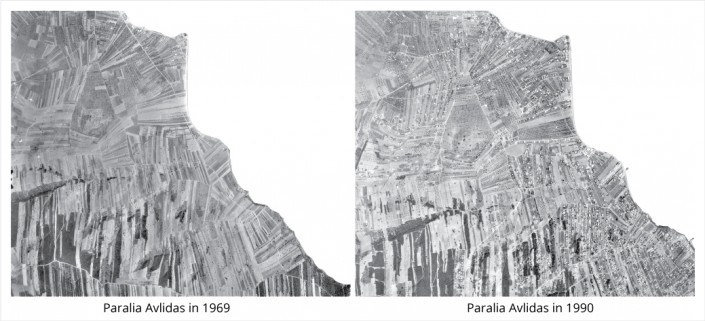

Leisure housing in peri-urban areas has rapidly changed their profile, as can be witnessed by the example of the community of Paralia Avlidas (photos 1a and 1b). The less distant areas and those that acquired new transportation infrastructure, started their transformation –partially at least– to principal residence areas. The suburban rail and the regional highways –mainly Attiki Odos– were a catalyst in this process (map 3).

Photos 1a and 1b: Aerial photos of Paralia Avlidas, Prefecture of Evia (1969 and 1990)

Source: Hellenic Military Geographical Service

The general pattern in the spatial distribution of vacant houses shows that, in general, they are not located in areas where they could be used to tackle the problem of housing needs, since the latter are mainly located in the densely built areas of large cities. However, this first conclusion is only partly true.

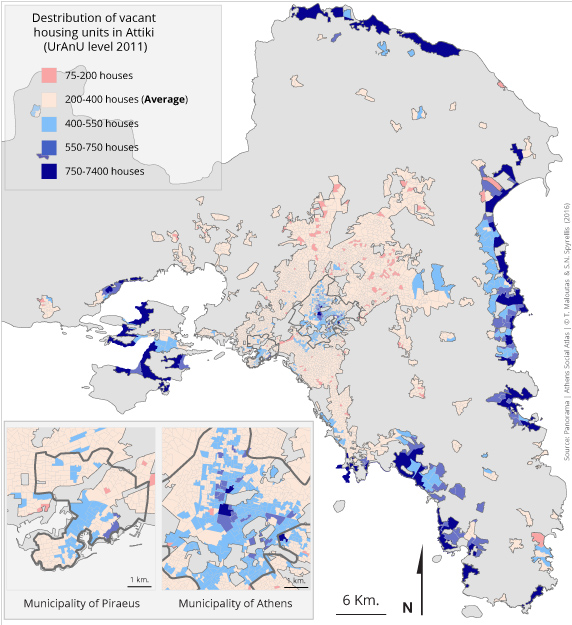

The mapping of vacant houses in Attiki for 2011 (map 2) offers a clearer view of their localization pattern in the region and some more insight concerning their potential use.

Map 2: Number of vacant houses in Attiki by URANU [1] (2011)

Map 2 shows that the largest concentrations of vacant houses are located in the coastal regions, mainly in the northern and eastern part of Attiki as well as on the island of Salamis. This pattern coincides absolutely with the location of vacation and weekend areas. However, two other important concentrations are also observed in the centres of Athens and Piraeus.

Table 1 confirms that the higher number of vacant houses in respect their population is also observed in the coastal areas of Attiki and in its islands most of which are not shown in map2. On the contrary, lower numbers are observed in municipalities located in the first suburban ring, most of which are inhabited mainly by middle and upper-middle social strata.

Table 1a: The 15 Municipalities in the Region of Attiki with the highest number of vacant houses per 100 inhabitants (2011)

Table 1b: The 10 Municipalities in the Region of Attiki with the lowest number of vacant houses per 100 inhabitants (2011)

Source: Panorama of Greek Census Data 1991-2011

According to the census, there were 608.500 vacant houses in Attiki in 2011 marking an increase by 265.500 (77,3%) from 2001. The spatial concentration –in absolute numbers as well as in percentage– is located in the region’s periphery. The central municipalities of Athens and Piraeus contain 132.000 (21,7%) and 27.300 (4,5%) vacant units respectively. These percentages are slightly higher than their specific population weight (17,3% for Athens and 4,3% for Piraeus).

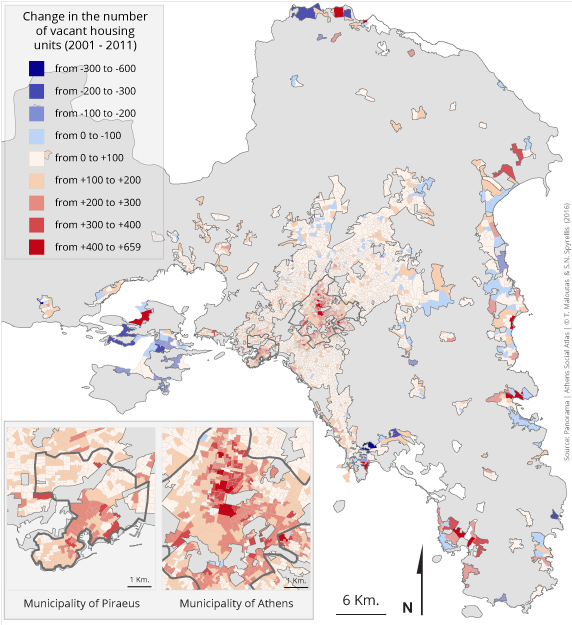

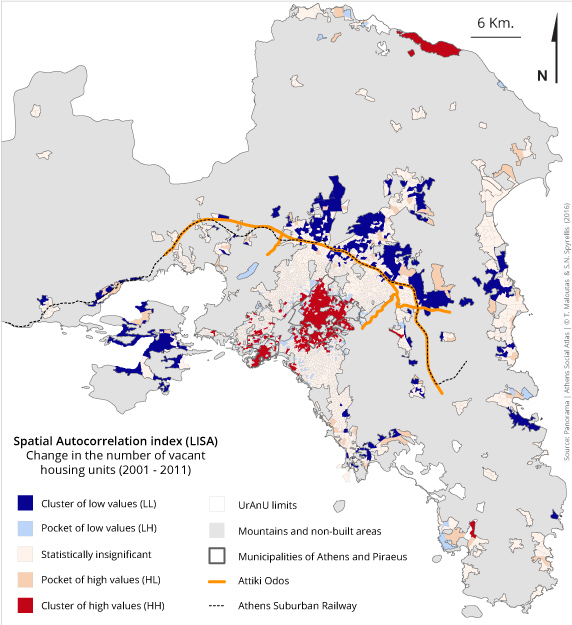

Map 3: Changes in the number of vacant houses in Attiki by URANU [1] (2011)

Map 3 shows that certain peripheral areas in Attiki (east coast and Messogeia, Oropos area, Vari, Salamis) witnessed a decrease in the number of vacant houses compared to 2001. This may be due to the increase of the rate of principal residences in the territory of some of these areas, following the conversion of former leisure houses, which were registered as vacant. This explanation is supported by the fact that these areas are serviced by the new important transport infrastructures –mainly by the peripheral highway, Attiki Odos. However, this trend may be also due to the fact that the 2011 census occurred in May, instead of March in 2001; and this may have decreased the number of leisure houses that were not found vacant in 2011 in areas like Salamis. At the same time, according to map 4 and table 2, the rate of increase of vacant houses during the 2000s has been much higher in the city’s central areas.

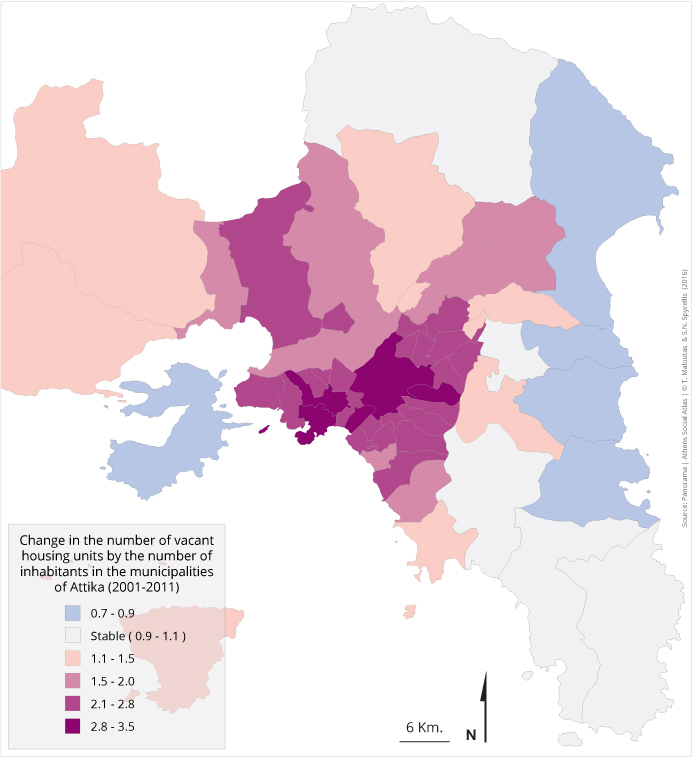

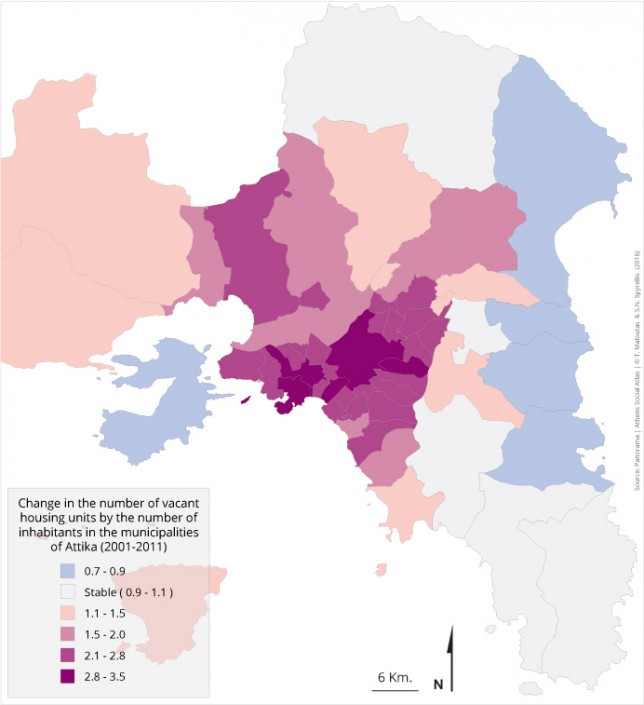

Map 4: Rate of increase of the index vacant houses by number of inhabitants in the municipalities of Attiki (2001-2011)

Table 2a: The 15 Municipalities in the Region of Attiki with the highest rate of increase of vacant houses (2001-2011)

Table 2b: The 10 Municipalities in the Region of Attiki with the lowest rate of increase of vacant houses (2001-2011)

Source: Panorama of Greek Census Data 1991-2011

Table 2 shows that the dynamic increase of vacant houses during the 2000s does not originate from the areas where their large percentages traditionally concentrate, i.e. from the most peripheral and coastal areas of the region. The 10 municipalities with the lowest rates of increase belong in fact to this type of areas with the highest percentages of vacant houses.

On the contrary, the rapid increase during the 2000s is mainly observed in the densely built areas of the metropolis comprising the two main centres of Athens and Piraeus, as well as municipalities in their immediate surroundings like Zografou, Kallithea, Galatsi, and Vyron for Athens and Nikaia, Korydallos, Perama and Keratsini for Piraeus.

Examining the profile of members of the two groups of municipalities in table 2, one can assume that there is no mono-causal explanation regarding the rapid increase of vacant houses during the 2000s.

Map 5 -which depicts not only the rate of change in vacant housing by spatial unit but also takes into account the spatial proximity of units with similar patterns of change- shows important differences between the centre and parts of the periphery in ways that indicate clearly the importance of new transport infrastructures and networks, namely Attiki Odos and the suburban rail.

- The central municipalities and those around them register high rates of increase in the number of vacant houses due to the persistent trend of moving to the suburbs, to the defensive family strategies aiming at reducing housing expenses through moving to smaller units and/or cohabitation with other family members, as well as due to the limited demand for housing in the densely built areas of the centre following their stigmatization and the reduced purchasing power of households that would be willing to settle in these areas.

- In the expensive suburbs (Filothei-Psychico, Papagou-Cholargos, Palaio Faliro) the important increase in vacant houses may be attributed to abandoned tenancies due to the crisis, but also to the greater ability of property owners to resist letting or selling them at lower price levels in comparison to the city’s average property owner.

Map 5: Clusters and enclaves of high and low changes in the number of vacant housing units (2001-2011)

| Spatial autocorrelation refers to the degree of correlation between pairs of a variable’s values and the (spatial) distance between them. The rationale behind this approach is based on the comparison between the value -the variable to be examined- of each territorial unit with a distribution of the values of neighbouring spatial units.Positive autocorrelation, which is the most common case, suggests that similar/equal values of the examined variable tend to cluster in space. Values may concentrate in the upper end {high value cluster [HH- (High-High)]} or in the lower end of the distribution {low value cluster [LL- (Low- Low)]}.

A negative autocorrelation indicates the proximity of spatial units with similar or dissimilar values. This either results in individual spatial units with high values within broader zones with low values {high value pocket [HL- (High-Low)}, or in spatial units with relatively low values enclosed by areas with high values {low price pocket [LH- (low-high)}. Finally, the lack of spatial autocorrelation signifies that there is no apparent relation between spatial proximity and the distribution of the variable’s values |

As a conclusion, we can claim that, even though the largest part of vacant houses in Attiki comprises leisure homes located at the coastal periphery of the region, the important increase in their number during the 2000s occurred in central areas of the conurbation, namely in the municipalities of Athens and Piraeus. Vacant houses in these areas –which have been unequally hit by the crisis due to their socially vulnerable population and the long-lasting tendency of their middle and upper-middle strata to abandon them for the suburbs– are an important resource that cannot be neglected when devising policies to revitalize inner-city areas with a focus on supporting their vulnerable inhabitants.

[1] Urban Analysis Units. They are a corrected form of Census Tracts (CT) used by ELSTAT in the sense that small CTs have been aggregated in order to avoid units with less than 900 inhabitants. This operation was performed to avoid confidentiality issues. Attiki is divided into 3.000 URANUs with an average population of 1.250 persons.

Entry citation

Maloutas, T., Spyrellis, S. (2016) Vacant houses, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/vacant-houses/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.63

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Μαλούτας Θ (1990) Αθήνα, κατοικία, οικογένεια. Ανάλυση των μεταπολεμικών πρακτικών στέγασης. Αθήνα: ΕΚΚΕ, Εξάντας.

- Μαλούτας Θ (2000) Αστικοποίηση και κενές κατοικίες. Στο: Μαλούτας Θ (επιμ.), Κοινωνικός και Οικονομικός Άτλας της Ελλάδας. Οι πόλεις, Αθήνα, Βόλος: Εθνικό Κέντρο Κοινωνικών Ερευνών, Gutenberg, Γιώργος & Κώστας Δαρδανός, Πανεπιστημιακές Εκδόσεις Θεσσαλίας, σσ 24–25.

- De Grauwe P and Ji Y (2013) Are Germans really poorer than Spaniards, Italians and Greeks? Vox. Available from: http://voxeu.org/article/are-germans-really-poorer-spaniards-italians-and-greeks.

- Maloutas T (2003) Les habitations vacantes. In: Sivignon M, Deslondes O, and Maloutas T (eds), Atlas de la Grèce, Paris: CNRS – Libergéo – La Documentation Française, pp. 70–71.

- The Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Network (2013) Statistical Tables to the Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Survey. Frankfurt. Available from: http://www.ecb.europa.eu/home/pdf/research/HFCS_Statistical_Tables_Wave1.pdf?93617b19d03b9491c9e7adde682e7688.

- The Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Network (2013) The Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Survey-Results from the First Wave. Frankfurt.

- Wilson J (2013) Poor Germans tire of bailing out Eurozone. Financial Times, Frankfurt, 22nd March. Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/2f89e5ee-930a-11e2-9593-00144feabdc0.